|

by Martin Lukacs

15 October 2012

from

TheGuardian Website

World's Biggest Geoengineering

Experiment

'Violates' United Nations Rules.

Controversial U.S. businessman's iron fertilization

off west coast of Canada contravenes

two UN conventions.

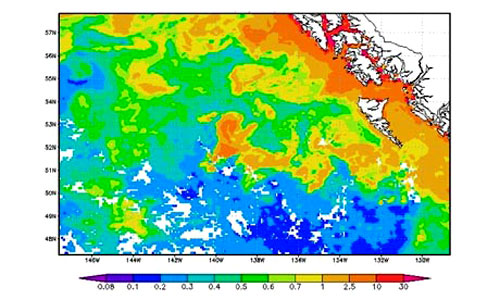

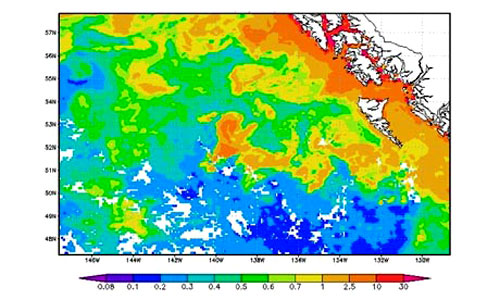

Geoengineering with bloom - high concentrations of

chlorophyll in the Eastern Gulf of Alaska

Yellow and brown colors show relatively high

concentrations of chlorophyll in August 2012,

after

iron sulphate was dumped into the Pacific Ocean as

part of a controversial geoengineering scheme.

Photograph: Giovanni/Goddard Earth Sciences Data and

Information Services Center/NASA

A controversial American businessman dumped around 100 tonnes of

iron sulphate into the Pacific Ocean as part of a geoengineering

scheme off the west coast of Canada in July, a Guardian

investigation can reveal.

Lawyers, environmentalists and civil society groups are calling it a

"blatant violation" of two international moratoria and the news is

likely to spark outrage at a United Nations environmental summit

taking place in India this week.

Satellite images appear to confirm the claim by Californian

Russ George that the iron has

spawned an artificial plankton bloom as large as 10,000 square

kilometers. The intention is for the plankton to absorb carbon

dioxide and then sink to the ocean bed - a geoengineering technique

known as ocean fertilization that he hopes will net lucrative carbon

credits.

George is the former chief executive of

Planktos Inc, whose previous failed

efforts to conduct large-scale commercial dumps near the Galapagos

and Canary Islands led to his vessels being barred from ports by the

Spanish and Ecuadorean governments.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) warned him that flying a U.S. flag for his Galapagos project would

violate U.S. laws, and his activities are credited in part to the

passing of international moratoria at the United Nations limiting

ocean fertilization experiments

Scientists are debating whether iron fertilization can lock carbon

into the deep ocean over the long term, and have raised concerns

that it can irreparably harm ocean ecosystems, produce toxic tides

and lifeless waters, and worsen ocean acidification and global

warming.

"It is difficult if not impossible

to detect and describe important effects that we know might

occur months or years later," said John Cullen , an

oceanographer at Dalhousie University.

"Some possible effects, such as

deep-water oxygen depletion and alteration of distant food webs,

should rule out ocean manipulation. History is full of examples

of ecological manipulations that backfired."

George says his team of unidentified

scientists has been monitoring the results of the biggest ever

geoengineering experiment with equipment loaned from U.S. agencies

like NASA and the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration.

He told the Guardian that it is the,

"most substantial ocean restoration

project in history," and has collected a "greater density and

depth of scientific data than ever before".

"We've gathered data targeting all the possible fears that have

been raised [about ocean fertilization]," George said. "And the

news is good news, all around, for the planet."

The dump took place from a fishing boat

in an eddy 200 nautical miles west of the

islands of Haida Gwaii, one of the

world's most celebrated, diverse ecosystems, where George convinced

the local council of an indigenous village to establish the

Haida Salmon Restoration Corp.

to channel more than $1m of its own funds into the project.

The president of the Haida nation, Guujaaw, said the village was

told the dump would environmentally benefit the ocean, which is

crucial to their livelihood and culture.

"The village people voted to support

what they were told was a 'salmon enhancement project' and would

not have agreed if they had been told of any potential negative

effects or that it was in breach of an international

convention," Guujaaw said.

International legal experts say George's

project has contravened the UN's convention on biological

diversity (CBD) and London convention on the dumping of wastes

at sea, which both prohibit for-profit ocean fertilization

activities.

"It appears to be a blatant

violation of two international resolutions," said Kristina M

Gjerde, a senior high seas adviser for the International Union

for Conservation of Nature.

"Even the placement of iron

particles into the ocean, whether for carbon sequestration or

fish replenishment, should not take place, unless it is assessed

and found to be legitimate scientific research without

commercial motivation. This does not appear to even have had the

guise of legitimate scientific research."

George told the Guardian that the two

moratoria are a "mythology" and do not apply to his project.

The parties to the UN CBD are currently meeting in Hyderabad, India,

where the governments of,

...are calling for

the current moratorium to be upgraded to a comprehensive test ban of geoengineering that includes enforcement mechanisms.

"If rogue geoengineer Russ George

really has misled this indigenous community, and dumped iron

into their waters, we hope to see swift legal response to his

behavior and strong action taken to the heights of the Canadian

and U.S. governments," said Silvia Ribeiro of the international

technology watchdog

ETC Group, which first discovered the

existence of the scheme.

"It is now more urgent than ever

that governments unequivocally ban such open-air geoengineering

experiments. They are a dangerous distraction providing

governments and industry with an excuse to avoid reducing fossil

fuel emissions."

Ocean Fertilization

'Rogue Climate Hacker' Russ George Raises

Storm of Controversy

by Margaret Munro

October 19, 2012

from

VancouverSun Website

President of

the Haida Salmon Restoration Corp. John Disney

addresses media

during a news conference at

the Vancouver Aquarium in Vancouver, Friday,

Oct. 19, 2012.

Photograph by: Jonathan Hayward , CP

VANCOUVER

Russ George

doesn't think small.

He got the Vatican to buy into a venture to reduce its carbon

footprint by growing a forest in Hungary.

He sailed off to the Galapagos Islands in 2007 with a grand plan to

scatter iron over a large swath of the South Pacific.

And now George is leading the world's largest ocean-fertilization

experiment off the B.C. coast, which was widely denounced this week

as shoddy science and a violation of international rules.

George is the kind of can-do entrepreneur - or "rouge climate

hacker" as he was described this past week - that makes some worry

about unauthorized experiments putting the planet at risk.

It's the ocean this time, and the experiment will likely do no

serious damage, says Ken Denman, an oceanographer at the

University of Victoria.

Next time, he says, it could be some

multimillionaire or "rogue" country shooting sulfate aerosols into

the atmosphere to block incoming solar radiation in a bid to slow

global warming.

"That's the big worry," says Denman,

a former Fisheries and Oceans Canada scientist who has spent

years working on international efforts to better protect the

global atmosphere and oceans.

Environment Canada's Enforcement Branch

is investigating George's B.C. experiment, which scattered 100

tonnes of iron in waters off the windswept islands of Haida Gwaii.

But Denman notes that the iron was scattered outside the 200-mile

exclusive economic zone, where Canada has no jurisdiction.

And while critics call George's experiment a "blatant violation" of

international agreements, Denman says the regulations "have no

teeth." The London Convention permits "legitimate scientific

research" and that is open to broad interpretation.

John Disney, CEO of the

Haida Salmon Restoration Corp.

that's running the experiment, says several federal departments,

including Environment Canada and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern

Development Canada, were aware of the experiment long before the

iron was scattered into the sea in July spawning what is said to be

a huge plankton bloom covering as many as 10,000 square kilometers.

And he insists the experiment does not violate Canadian laws or

international conventions.

"We consulted three sets of

lawyers," says Disney.

George, the chief scientist on the

project, was not available for an interview.

"He's sitting under a mountain of

data," says Disney, who was fielding media queries.

He describes George is "an absolute

genius" who know how to get things done.

George is also considered a "rouge climate hacker," as Britain's New

Scientist put it this week, who has been running questionable

projects for years.

George's California company,

Planktos Corp., backed by Vancouver

financier Nelson Skalbania, tried to scatter tonnes of iron

dust into the water near the Galapagos Islands in 2007 in the first

attempt to make money from ocean fertilization.

George sailed off in a 115-foot-long ship, the Weatherbird II, with

a plan to fertilize almost a million hectares of the South Pacific

to get algae to grow, creating a phytoplankton bloom. The algae,

George told investors, would suck carbon dioxide out of the

atmosphere, which could then be used to generate lucrative carbon

credits.

Critics denounced the plan as a misguided "geoengineering" scheme,

and the government of Ecuador barred the Weatherbird II from its

ports. George then changed course and headed for the Canary Islands

in the Atlantic Ocean but Spanish officials preventing him from

coming into port.

George also made headlines when Planktos teamed up with the Vatican

to make the Holy See what he called "the first entirely carbon

neutral sovereign state" by planting a forest in Hungary.

George presented Cardinal Paul Poupard, head of the

Pontifical Council for Culture, with carbon offset certificates at a

Vatican ceremony announcing the plan in July 2007.

The Vatican project reportedly fell through when Planktos

Corp. went bankrupt.

Disney, who had worked with George on Canadian forest projects, says

he approached him about returning to British Columbia when Planktos'

fortunes sank.

"When things started going sideways

I said, 'You know Russ, maybe it's time to form a relationship

here,'" says Disney.

He describes George as an "activist

scientist" who takes complex scientific ideas and theories and

applies them in the real world.

"That's what he's an absolute genius

at, that's why we hired him," says Disney, whose corporation

runs out of the Old Massett Village Council on the north end of

Haida Gwaii.

"We didn't want to go too much with a straight academic as our

lead because then it's going to be too rigid, too controlled,"

says Disney.

George came up with a plan to "bring

life back to the North Pacific," says Disney.

Spreading iron in the sea would act like

fertilizer, boost plankton growth, and provide more food for salmon

that have been serious decline in the rivers of

Haida Gwaii, according to the plan.

The impoverished First Nations community of Old Massett, home to 750

people and a 70 per cent unemployment rate, held a vote and was so

keen it invested $2.5 million in the project.

The community hopes to recover some of its investment through

selling carbon credits for removing carbon from the atmosphere and

locking in into the sea.

"There are lots of options out

there," says Disney.

James Tansey, associate professor

at the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business,

said he doubts they'll find a buyer anytime soon.

At least, he says, not on the regulated

carbon markets, such as the ones in British Columbia and Alberta

that require third party "validation and verification" that carbon

has been removed from the atmosphere.

"I can tell you none of the

regulated buyers would touch it," says Tansey, who says

"cowboys" such as George do little to build credibility for

carbon trading.

Tansey works with several B.C. First

Nations communities now selling carbon credits for preserving

forests.

He notes that ocean fertilization is far

more complex and controversial.

"You'd have to prove that when you

add iron to the ocean it has a real affect," says Tansey, who

said he doubts George's team will be able to provide the

evidence needed.

Disney says the HSRC science team spent

almost two months at sea this summer.

Since spreading the iron over an expanse of water known as a Haida

eddy, he says they have been monitoring the resulting plankton bloom

with a suite of instruments, including metre-long collection

bottles, biomass sonars and bright yellow underwater "gliders"

programmed to zip through the water collecting data.

They are also using 20 Argos "drifterbots,"

from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to

track the plankton bloom as the winds and currents push it around.

NOAA provided the equipment, but the New

York Times reports that George "duped" the agency. An agency

spokesperson told the Times that NOAA had been "misled" by George's

group, which,

"did not disclose that it was going

to discharge material into the ocean."

George reports in a recent Human

Sciences Research Council newsletter that the "pioneering" project

has had a dramatic impact.

"The waters of the Haida eddy have

turned from clear blue and sparse of life into a verdant emerald

sea lush with the growth of a hundred million tonnes of plankton

and the entire food chain it supports," it says.

"The growth of those tonnes of plankton derives from vast

amounts of CO2 now diverted from becoming deadly

ocean acid and instead made that same CO2 become

ocean life itself."

Denman, who has been involved in

small-scale iron fertilization projects in the North Pacific, does

not buy it.

He says the plankton bloom could have occurred naturally because it

is well known that the enormous eddies that form west of the Haida

Gwaii are enriched by coastal waters carrying iron and nitrogen.

Denman, and many other scientists, say they doubt George will be

able to prove the added iron had an impact on the plankton, salmon

or that carbon dioxide was removed from the atmosphere.

The people in Old Massett have "been totally misled," says Denman.

Some do believe the experiment does have some validity.

"While I agree that the procedure

was scientifically hasty and controversial, the purpose of

enhancing salmon returns by increasing plankton production has

considerable justification," says Timothy Parsons, a fisheries

scientist and professor emeritus at the University of B.C.

The waters of the Gulf of Alaska are so

nutrient poor they are a,

"virtual desert dominated by jelly

fish," says Parsons.

His research has helped show that

iron-rich volcanic dust stimulates growth of diatoms, a form of

algae that he describes as "the clover of the sea."

And he points to volcanic eruptions over the Gulf of Alaska in 1958

and 2008 that,

"both resulted in enormous sockeye

salmon returns."

John Nightingale, president of

the Vancouver Aquarium, was one of several scientists approached

about a year and half ago when George's team was looking for

scientific supporters.

He was initially taken aback by the ocean fertilization plan.

"My first reaction was 'Oh my

goodness, this is playing with Mother Nature on a grand scale,'"

Nightingale says.

After learning more about the project,

he decided adding iron to the ocean to see if it could increase

salmon production was a reasonable thing to try.

"The scientific questions at its

core are valid," says Nightingale.

Many argue such experiments should be

done in a carefully controlled, multi-year, step-by-step manner.

But Nightingale says,

"that was clearly never going to

happen" given dwindling federal funds for ocean research.

Now that the experiment has been done,

Nightingale says George and his team must be transparent with the

data collected.

"The results are really important,"

he says, and need to be vetted by the scientific community and

distributed widely.

"Out of that will come some direction and no longer will it just

be what the Haida decide to do," says Nightingale. He expects

the pubic visibility "to create a set of safeguards going

forward."

|