|

from

Crytalinks Website

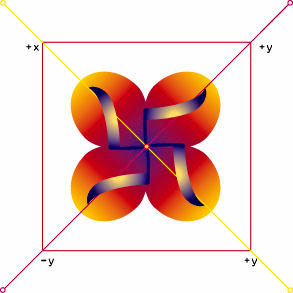

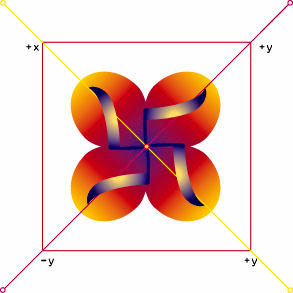

The symbol of the 4-sided swastika is an

archetype for the rotations of time and consciousness - moving

clockwise and counterwise - in upward or downward spirals - allowing

souls to experience many levels of reality simultaneously.

The word Swastika comes from the

Sanskrit words su, meaning well, and asti,

meaning to be.

The swastika is an equilateral cross with its arms bent at right

angles either clockwise or anticlockwise. It is traditionally

oriented so that a main line is horizontal, though it is

occasionally rotated at forty-five degrees, and the Hindu version

often has a dot in each quadrant.

The swastika has not always been used as a symbol of Nazism and was

in fact borrowed from Eastern cultures. It seems to have first been

used by early inhabitants of Eurasia. It is an important symbol in

Eastern religions, notably Hinduism and Buddhism, among others, and

was also used in Native American faiths before World War II.

By the

early twentieth century it was regarded worldwide as a symbol of

good luck and auspiciousness. Swastikas appeared on the spines of

books by the Anglo-Indian writer Rudyard Kipling, and the symbol was

used by Robert Baden-Powell's Boy Scout movement.

Since the rise of the National Socialist German Workers Party, the

swastika has been associated with fascism, racism,

World War II, and

the Holocaust in much of the western world. Before this, it was

particularly well-recognized in Europe from the archaeological work

of Heinrich Schliemann, who discovered the symbol in the site of

ancient Troy and who associated it with the ancient migrations of

Indo-European (Aryan) peoples.

Nazi use derived from earlier German völkisch nationalist movements, for which the swastika was a symbol

of "Aryan" identity, a concept that came to be equated by theorists

like Alfred Rosenberg with a Nordic master race originating in

northern Europe. The swastika remains a core symbol of Neo-Nazi

groups.

Since the end of World War II, the traditional uses of swastika in

the western world were discouraged. Many innocent people or products

were wrongly persecuted.

There have been failed attempts by

individuals and groups to educate Westerners to look past the

swastika's recent association with the Nazis to its prehistoric

origins.

Etymology and

alternative names

The word swastika is derived from the Sanskrit svastika, meaning any

lucky or auspicious object, and in particular a mark made on persons

and things to denote good luck.

It is composed of su- (cognate with

Greek ευ-), meaning "good, well" and asti a verbal abstract to the

root as "to be"; svasti thus means "well-being".

The suffix -ka

forms a diminutive, and svastika might thus be translated literally

as "little thing associated with well-being", corresponding roughly

to "lucky charm", or "thing that is auspicious". The word first

appears in the Classical Sanskrit (in the Ramayana and Mahabharata

epics).

Alternative historical English spellings of the Sanskrit word

include suastika and svastica. Alternative names for the shape are:

-

Crooked cross

-

Cross cramponned - in heraldry,

as each arm resembles a crampon or angle-iron

-

Cross gammadion - tetragammadion

or just gammadion, as each arm resembles the Greek letter

(gamma)

-

Fylfot - meaning "four feet",

chiefly in heraldry and architecture

-

Sun wheel - German Sonnenrad - a

name also used as a synonym for the sun cross

-

Tetraskelion - Greek "four

legged", especially when composed of four conjoined legs

-

Thor's hammer - from its

supposed association with Thor, the Norse god of thunder,

but this may be a misappropriation of a name that properly

belongs to a Y-shaped or T-shaped symbol. - The Swastika

shape appears in an 8th century Icelandic grimoire where in

it is named Þurs Hamar

-

Hooked cross - (Dutch:

hakenkruis, Icelandic Hakakross, German: Hakenkreuz,

Finnish: hakaristi, Norwegian: Hakekors, Italian: croce

uncinata and Swedish: Hakkors)

-

Black Spider - to various

peoples in middle and western Europe

History

The swastika appears in art and design from pre-history symbolizing,

in various contexts: luck, the sun, Brahma, or the Hindu concept of

samsara.

In antiquity, the swastika was used extensively by

Hittites, Celts and Greeks, among others. It occurs in other Asian,

European, African and Native American cultures sometimes as a

geometrical motif, sometimes as a religious symbol. Today, the

swastika is a common symbol in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, among

others.

The ubiquity of the swastika has been explained by three main

theories: independent development, cultural diffusion, and external

event. The first theory is that the swastika's symmetry and

simplicity led to its independent development everywhere, along the

lines of Carl Jung's collective unconscious, or just as a very

simple symbol.

Another explanation is suggested by

Carl Sagan in his book Comet.

Sagan reproduces an ancient Chinese manuscript that shows comet tail

varieties: most are variations on simple comet tails, but the last

shows the comet nucleus with four bent arms extending from it,

recalling a swastika. Sagan suggests that in antiquity a comet could

have approached so close to Earth that the jets of gas streaming

from it, bent by the comet's rotation, became visible, leading to

the adoption of the swastika as a symbol across the world.

Theories of single origin as a sacred prehistorical symbol point to

the Proto-Indo-Europeans, noting that the swastika was not adopted

by Sumer in Mesopotamia, which was established no later than 3500

BC, and the Old Kingdom of Egypt, beginning in 2630 BC, arguing that

these were already well-established and codified at the time of the

symbol's diffusion. As an argument ex silentio, this point has

little value as a positive proof.

The swastika symbol is prominent in Hinduism, which is considered

the parent religion of Buddhism and Jainism, both dating from about

the sixth century BC, and both borrowing the swastika from their

parent. Buddhism in particular enjoyed great success, spreading

eastward and taking hold in southeast Asia, China, Korea and Japan

by the end of the first millennium.

The use of the swastika by the

indigenous Bön faith of Tibet, as well as syncretic religions, such

as Cao Dai of Vietnam and Falun Gong of China, is thought to be

borrowed from Buddhism as well. Similarly, the existence of the

swastika as a solar symbol among the Akan civilization of southwest

Africa may have been the result of cultural transfer along the

African slave routes around 1500 AD.

Regardless of origins, the swastika had generally positive

connotations from early in human history, with the exceptions being

most of Africa and South America.

Adoption of

the swastika in the West

The discovery of the Indo-European language group in the 1800s led

to a great effort by archaeologists to link the pre-history of

European peoples to the ancient Aryans.

Following his discovery of

objects bearing the swastika in the ruins of Troy, Heinrich

Schliemann consulted two leading Sanskrit scholars of the day,

Emile Burnouf and Max Müller.

Schliemann concluded that the swastika was a

specifically Aryan symbol. This idea was taken up by many other

writers, and the swastika quickly became popular in the West,

appearing in many designs from the 1880s to the 1920s.

The positive meanings of the symbol were subverted in the early

twentieth century when it was adopted as the emblem of the National

Socialist German Workers Party.

This association occurred because Nazism stated that the historical Aryans were the modern Germans and

then proposed that, because of this, the subjugation of the world by

Germany was desirable, and even predestined.

The swastika was used

as a convenient symbol to emphasize this mythical Aryan-German

correspondence.

Since World War II, most Westerners see the swastika

as solely a Nazi symbol, leading to incorrect assumptions about its

pre-Nazi use and confusion about its current use in other cultures.

Geometry and

Symbolism

A right-facing swastika may be described as "clockwise"...... or

"counter-clockwise". A swastika composed of 17 squares in a 5x5 grid.

Geometrically, the swastika can be regarded as an irregular icosagon

or 20-sided polygon. The arms are of varying width and are often

rectilinear (but need not be). Only in modern use are the exact

proportions considered important: for example, the proportions of

the Nazi swastika were based on a 5x5 grid.

The swastika is chiral, with no reflectional symmetry, but both

mirror-image forms have 90° rotational symmetry (that is, the

symmetry of the cyclic group C4).

A right-facing

swastika may be described as "clockwise"...

.. or "counter-clockwise"

A swastika composed of 17 squares in a 5x5 grid

The mirror-image forms are often

described as:

"Left-facing" and "right-facing" are

used mostly consistently.

Looking at an upright swastika, the upper

arm clearly faces towards the viewer's left (SM) or right (SP). The

other two descriptions are ambiguous as it is unclear if they refer

to the direction of the bend in each arm or to the implied rotation

of the symbol. If the latter, the question as to whether the arms

lead or trail remains. The terms are used inconsistently (sometimes

even by the same writer) which is confusing and may obfuscate an

important point, that the rotation of the swastika may have symbolic

relevance.

The swastika is, after the simple equilateral cross (the "Greek

cross"), the next most commonly found version of the cross.

Seen as a cross, the four lines emanating from the center point to

the four cardinal directions. The most common association is with

the Sun.

Other proposed correspondences are to the visible rotation

of the night sky in the Northern Hemisphere around Polaris.

Sauwastika

The name sauwastika is sometimes given for the supposedly "evil",

left-facing, form of the swastika (SM).

However, the evidence for

sauwastika seems sketchy and there seems to be very little other

than conjecture to support the notion that the left-facing swastika

is regarded as evil in Hindu tradition. Although the more common

form is the right-facing swastika, Hindus all over India and Nepal

still use the symbol in both orientations for the sake of balance.

Buddhists almost always use the left-facing swastika.

Some contemporary writers - Servando Gonzalez, for example - confuse

matters even further by asserting that the right-facing swastika,

used by the Nazis is in fact the "evil" sauwastika. (Gonzalez

"proves" that the left-facing swastika is the sunwise one with

reference to a 1930s box of Standard fireworks from Sivakasi,

India.)

This inversion whether intentional or not might derive

from a desire to prove that the Nazi's use of the right-handed

swastika was expressive of their "evil" intent.

But the notion that

Adolph Hitler deliberately inverted the "good left-facing" swastika

is wholly unsupported by any historical evidence.

Art and

Architecture

The swastika is common as a design motif in current Hindu

architecture and Indian artwork as well as in ancient Western

architecture, frequently appearing in mosaics, friezes, and other

works across the ancient world.

Ancient Greek architectural designs

are replete with interlinking swastika motifs. Related symbols in

classical Western architecture include the cross, the three-legged

triskele or triskelion and the rounded lauburu.

The swastika symbol

is also known in these contexts by a number of names, especially

gammadion. Pictish rock carvings, adorning ancient Greek pottery,

and on Norse weapons and implements.

It was scratched on cave walls

in France seven thousand years ago.

In Chinese, Korean, and Japanese art,

the swastika is often found as part of a repeating pattern.

One

common pattern, called sayagata in Japanese, comprises left and

right facing swastikas joined by lines. As the negative space

between the lines has a distinctive shape, the sayagata pattern is

sometimes called the "key fret" motif in English.

The swastika symbol was found extensively in the ruins of the

ancient city of Troy.

In Greco-Roman art and architecture, and in Romanesque and Gothic

art in the West, isolated swastikas are relatively rare, and the

swastika is more commonly found as a repeated element in a border or

tesselation. A design of interlocking swastikas is one of several

tesselations on the floor of the cathedral of Amiens, France.

A

border of linked swastikas was a common Roman architectural motif,

and can be seen in more recent buildings as a neoclassical element.

A swastika border is one form of meander, and the individual

swastikas in such border are sometimes called Greek Keys.

The Laguna Bridge in Yuma, Arizona was built in 1905 by the U.S.

Reclamation Department and is decorated with a row of swastikas.

The Canadian artist ManWoman has attempted to rehabilitate the

"gentle swastika."

Religion and

Mythology

Hinduism

The swastika is found all over Hindu temples, signs, altars,

pictures and iconography in India and Nepal, where it remains

very popular.

It is considered to be the second most sacred symbol in

Hinduism, behind the Om symbol. In Hinduism, the two symbols

represent the two forms of the creator god Brahma: clockwise it

represents the evolution of the universe (Pravritti),

anti-clockwise it represents the involution of the universe (Nivritti).

It is also seen as pointing in all four directions (North, East,

South and West) and thus signifies stability and groundedness.

Its use as a sun symbol can first be seen in its representation

of Surya, the Hindu lord of the Sun.

The swastika is considered extremely holy and auspicious by all

Hindus, and is regularly used to decorate all sorts of items to

do with Hindu culture.

It is used in all Hindu yantras and religious designs.

Throughout the subcontinent of India it can be seen on the sides

of temples, written on religious scriptures, on gift items, and

on letterhead.

The Hindu God Ganesh is closely associated with the symbol of

the swastika.

Amongst the Hindus of Bengal, it is common to see the name

"swastika" applied to a slightly different symbol, which has the

same significance as the common swastika, and both symbols are

used as auspicious signs. This symbol looks something like a

stick figure of a human being.

"Swastika" is a common given name amongst Bengalis and a

prominent literary magazine in Calcutta is called the Swastika.

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the swastika is oriented horizontally.

These two symbols are included, at

least since the Liao dynasty, as part of the Chinese language,

the symbolic sign for the character meaning "all", and

"eternality" (lit. myriad) and as SP which is seldom used.

A swastika marks the beginning of many Buddhist scriptures.

The swastikas (in either orientation) appear on the chest of

some statues of Gautama Buddha and is often incised on the soles

of the feet of the Buddha in statuary.

Because of the association with the right facing swastika with

Nazism, Buddhist swastikas after the mid 20th century are almost

universally left-facing.

This form of the swastika is often found on Chinese food

packaging to signify that the product is vegetarian and can be

consumed by strict Buddhists. It is often sewn into the collars

of Chinese children's clothing to protect them from evil

spirits.

Additionally, the left-facing swastika is found on Japanese maps

to indicate a temple.

The swastika used in Buddhist art and scripture is known in

Japanese as a manji, and represents Dharma, universal harmony,

and the balance of opposites. When facing left, it is the omote

(front) manji, representing love and mercy.

Facing right, it represents strength and intelligence, and is

called the ura (rear) manji. Balanced manji are often found at

the beginning and end of Buddhist scriptures.

Jainism

In Jainism, the swastika symbol is the only holy symbol.

Jainism

does not use the Hindu om symbol at all and thus gives even more

prominence to the swastika than Hinduism. It is a symbol of the

seventh Jina (Saint), the Tirthankara Suparsva.

It is considered

to be one of the 24 auspicious marks and the emblem of the

seventh arhat of the present age. All Jain temples and holy

books must contain the swastika and ceremonies typically begin

and end with creating a swastika mark several times with rice

around the altar.

The Abrahamic religions

The swastika was not

widely utilized by followers of the Abrahamic religions.

Where

it does exist, it is not portrayed as an explicitly religious

symbol and is often purely decorative or, at most, a symbol of

good luck. The floor of the synagogue at Ein Gedi, built during

the Roman occupation of Judea, was decorated with a swastika.

Some Christian churches built in the Romanesque and Gothic eras

are decorated with swastikas, carrying over earlier Roman

designs. Swastikas are prominently displayed in a mosaic in the

St. Sophia church of Kiev, Ukraine dating to the 12th century.

They also appear as a repeating ornamental motif on a tomb in

the Basilica of St. Ambrose in Milan.

The Muslim "Friday" mosque

of Isfahan, Iran and the Taynal Mosque in Tripoli, Lebanon both

have swastika motifs.

Other Asian

Traditions

China

Falun Gong Emblem

Some sources indicate that the

Chinese Empress Wu (684-704) of the Tang Dynasty decreed that

the swastika would be used as an alternative symbol of the sun.

The Chinese character SP has developed into the modern one e¼,

pronounced f ng in Standard Mandarin, and has the main meaning

of "square". As part of the Chinese script, the swastika has

Unicode encodings U+534D SM (left-facing) and U+5350 SP

(right-facing).

The left-facing Buddhist swastika also appears on the emblem of Falun Gong. This has generated considerable controversy,

particularly in Germany, where the police have reportedly

confiscated several banners featuring the emblem.

A court

ruling subsequently allowed Falun Gong followers in Germany to

continue the use of the emblem.

Japan

In Japan, the swastika is called manji (SM).

On Japanese town

plans, a swastika (left-facing and horizontal) is commonly used

to mark the location of a Buddhist temple. The right-facing manji is often referred as the gyaku manji ("reverse manji"),

and can also be called kagi jokji, literally "hook cross." A

PokEmon playing card sold in Japan had a manji graphic.

Because

of its resemblance to the Nazi swastika (see below), the card

was altered for Western translations, and eventually withdrawn

in Japan following Western complaints.

Similarly, a manji symbol

was incorporated as a level design in both the Japanese and U.S.

versions of the 1986 The Legend of Zelda video game.

Native American Traditions

The swastika was a widely used Native American symbol. It has

been found in excavations of Mississippian-era sites in the Ohio

valley.

It was widely used by many southwestern tribes, most

notably the Navajo. Among different tribes the swastika carried

various meanings. To

the Hopi it represented the wandering Hopi

clans; to

the Navajo it was one symbol for a

whirling log (tsil

no'oli'), a sacred image representing a legend that was used in

healing rituals.

From The Book of the Hopi

by Frank Waters

The swastika symbol

represents the path of the migrations of the Hopi clans.

The center of the cross represents Tuwanasavi or the Center of

the Universe which lay in what is now the Hopi country in the

southwestern part of the US. Tuwanasavi was not the geographic

center of North America, but the magnetic or spiritual center

formed by the junction of the North-South and the East-West axis

along which the Twins sent their vibratory messages and

controlled the rotation of the planet.

Three directions (pasos) for most of the clans were the same:

the ice locked back door to the north, the Pacific Ocean to the

west and the Atlantic Ocean to the east.

Only 7 clans-the Bear, Eagle, Sun, Kachina, Parrot, Flute and

Coyote clans-migrated to South America to the southern paso at

it's tip. The rest of some 40 clans, having started from

somewhere in southern Mexico or Central America, regarded this

as their southern paso, their migration thus forming a balanced

symbol.

Upon arriving at each paso all the leading clans turned right

before retracing their routes.

Pre-Christian European Traditions

The swastika, also known

as the fylfot in northwestern Europe, appears on many

pre-Christian artifacts, drawn both clockwise and

counterclockwise, within a circle or in a swirling form.

The

Greek goddess Athena was sometimes portrayed as wearing robes

covered with swastikas.

The "Ogham stone" found in County Kerry,

Ireland is inscribed with several swastikas dating to the fifth

century AD, and is believed to have been an altar stone of the

Druids. The pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo,

England, contains gold cups and shields bearing swastikas.

Today

it is used as a symbol for Asatru, the reconstructed religion of

Northern Europe.

Early 20th Century

Europe

The British author Rudyard Kipling, who was strongly influenced

by Indian culture, had a swastika on the dust jackets of all his

books until the rise of Nazism made this inappropriate.

One of

Kipling's Just So Stories, "The Crab That Played With The Sea",

had an elaborate full-page illustration by Kipling including a

stone bearing what was called "a magic mark" (a swastika); some

later editions of the stories blotted out the mark, but not its

captioned reference, making the readers wonder what the "mark"

was.

The Russian Provisional Government of 1917 printed a number of

new bank notes with right-facing diagonally-rotated swastikars

in their centres. Some have suggested that this may have been

the inspiration behind the Nazis adoption of this symbol as

Alfred Rosenberg was in Russia at this time.

It was also used as a symbol by the Boy Scouts in Britain, and

worldwide. According to "Johnny" Walker,[14] the earliest

Scouting use was on the first Thanks Badge introduced in 1911.

Robert Baden-Powell's 1922 Medal of Merit design adds a swastika

to the Scout fleur-de-lis as good luck to the person receiving

the medal. Like Kipling, he would have come across this symbol

in India.

During 1934 many Scouters requested a change of design because

of the use of the swastika by the Nazis. A new British Medal of

Merit was issued in 1935.

The Lotta Svard emblem was designed by Eric Wasstrom in 1921. It

includes the swastika and heraldic roses.

During World War I, the swastika was used as the emblem of the

British National War Savings Committee.

In Finland the swastika was used as the official national

marking of the Finnish Air Force and Army between 1918 and 1944.

The swastika was also used by the Lotta Svard organization.

The blue swastika was the good luck

symbol used by the Swedish Count Erich von Rosen, who donated

the first plane to the Finnish White Army during the Civil War

in Finland.

It has no connection to the Nazi use of the

swastika. It also still appears in many Finnish medals and

decorations. In the very respected wartime medals of honor it

was a visible element, first drafted by Axel Gallen-Kallela

1918-1919.

Mannerheim cross with a swastika is

the Finnish equivalent of Victoria Cross, Croix de Guerre and

Congressional Medal of Honor. Due to Finland's alliance with

Nazi Germany in World War II, the symbol was abandoned as a

national marking, to be replaced by a roundel.

The Swedish company ASEA, now a part of Asea Brown Boveri, used

the swastika in its logo from the 1800s to 1933, when it was

removed from the logo.

In Latvia too, the swastika (known as Thunder Cross and

Fire

Cross) was used as the marking of the Latvian Air Force between

1918 and 1934, as well as in insignias of some military units.

It was also used by the Latvian fascist movement Perkonkrusts

(Thunder Cross in Latvian), as well as by other non-political

organizations.

The Icelandic Steamship Company, Eimskip (founded in 1914) used

a swastika in its logo until recently.

In Dublin, Ireland, a laundry company known as the Swastika

Laundry was in existence on the south side of the city.

Featuring a black swastika on a white background, the business

started up in the early 20th century and continued up until

recent times.

North America

The Theosophical Society, founded in New York in 1875,

incorporated the Swastika into its seal because of the Buddhist

associations of the symbol.

The swastika's use by the Navajo and other tribes made it a

popular symbol for the American Southwest. Until the 1930s

blankets, metalwork, and other Southwestern souvenirs were

often made with swastikas.

One year in the first part of the 20th century, the Corn Palace

in Mitchell, South Dakota featured a design that had a swastika

on one of the towers.

Swastika is the name of a small community in northern Ontario,

Canada, approximately 580 kilometers north of Toronto, and 5

kilometers west of Kirkland Lake, the town of which it is now

part. The town of Swastika was founded in 1906. Gold was

discovered nearby and the Swastika Mining Company was formed in

1908. The government of Ontario attempted to change the town's

name during World War II, but the town resisted.

In Windsor, Nova Scotia, there was an ice hockey team from

1905-1916 named the Swastikas, and their uniforms featured

swastika symbols. There were also hockey teams named the

Swastikas in Edmonton, Alberta (circa 1916), and Fernie, British

Columbia (circa 1922).

The 45th Infantry Division of the United States Army used a

yellow swastika on a red background as a unit symbol until the

1930s, when it was switched to a thunderbird.

In 1925, Coca Cola made a lucky watch fob in the shape of a

swastika with the slogan, "Drink Coca Cola five cents in

bottles".

The Health, Physical Education and Recreation Building (HPER) at

Indiana University contains decorative Native American-inspired

reverse swastika tilework on the walls of the foyer and

stairwells on the southeast side of the building. HPER was built

as the university fieldhouse in the 1920's, before the Nazi

party came to power in Germany. In recent years, the HPER

swastika motif, along with the Thomas Hart Benton murals in

nearby Woodburn Hall have been the cause of much controversy on

campus.

Nazi Germany

The National Socialist German Workers Party (Nationalsozialistische

Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP) formally adopted the swastika

or Hakenkreuz (hooked cross) in 1920. This was used on the

party's flag (right), badge, and armband.

(It had been used

unofficially by the NSDAP and its predecessor, the German

Workers Party, Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (DAP), however.)

In Mein Kampf, Adolph Hitler wrote:

I myself, meanwhile, after

innumerable attempts, had laid down a final form; a flag

with a red background, a white disk, and a black swastika in

the middle. After long trials I also found a definite

proportion between the size of the flag and the size of the

white disk, as well as the shape and thickness of the

swastika.

Red, white, and black were the

colors of the flag of the old German Empire.

The use of the swastika was associated by Nazi theorists with

their conjecture of Aryan cultural descent of the German people.

Following the Nordicist version of the Aryan invasion theory,

the Nazis claimed that the early Aryans of India, from whose

Vedic tradition the swastika sprang, were the prototypical white

invaders. Thus, they saw fit to co-opt the sign as a symbol of

the Aryan master race.

The use of swastika as a symbol of

the Aryan race dates back to writings of Emile Burnouf.

Following many other writers, the German nationalist poet Guido

von List believed it to be a uniquely Aryan symbol. Hitler

referred to the swastika as the symbol of "the fight for the

victory of Aryan man" - Mein Kampf.

The swastika was already in use as a symbol of German volkisch

nationalist movements. In Deutschland Erwache - Ulric of England

writes:

...what inspired Hitler to use

the swastika as a symbol for the NSDAP was its use by the

Thule-Gesellschaft since there were many connections between

them and the DAP... from 1919 until the summer of 1921 Hitler

used the special Nationalsozialistische library of Dr.

Friedich Krohn, a very active member of the Thule-Gesellschaft.

Dr. Krohn was also the dentist from Sternberg who was

named by Hitler in Mein Kampf as the designer of a flag very

similar to one that Hitler designed in 1920 during the

summer of 1920, the first party flag was shown at Lake

Tegernsee ... these home-made early flags were not

preserved, the Ortsgruppe München flag was generally

regarded as the first flag of the Party.

José Manuel Erbez wrote:

The first time the swastika was

used with an "Aryan" meaning was on December 25, 1907, when

the self-named Order of the New Templars, a secret society

founded by [Adolf Joseph] Lanz von Liebenfels, hoisted at

Werfenstein Castle (Austria) a yellow flag with a swastika

and four fleurs-de-lys.

However, Liebenfels was drawing on

an already-established use of the symbol.

NSDAP flags at the 1936 Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg. On 14 March

1933, shortly after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of

Germany, the NSDAP flag was hoisted alongside Germany's national

colors. It was adopted as the sole national flag on 15 September

1935.

The swastika was used for badges and flags throughout Nazi

Germany, particularly for government and military organizations,

but also for "popular" organizations such as the Reichsbund

Deutsche Jagerschaft.

Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg. On 14 March 1933, shortly after

Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany, the NSDAP flag

was hoisted alongside Germany's national colors. It was adopted

as the sole national flag on 15 September 1935.

The swastika was

used for badges and flags throughout Nazi Germany, particularly

for government and military organizations, but also for

"popular" organizations such as the Reichsbund Deutsche

Jägerschaft.

The Iron Cross

featured a swastika during the Nazi period

The Iron Cross featured a swastika

during the Nazi period - while the DAP and the NSDAP had used

both right-facing and left-facing swastikas, the right-facing

swastika is used consistently from 1920 onwards.

However, Ralf Stelter notes that the swastika flag used on land had a

right-facing swastika on both sides, while the ensign (naval

flag) had it printed through so that you would see a left-facing

swastika when looking at the ensign with the flagpole to the

right.

There were attempts to amalgamate Nazi and Hindu use of the

swastika. Notably by Savitri Devi Mukherji who declared Hitler

an avatar of Vishnu.

Taboo in Western Countries

Because of its use by Hitler and the Nazis and, in modern times,

by neo-Nazis and other hate groups, for many people in the West,

the swastika is associated primarily with Nazism, fascism, and

white supremacy in general. Hence, outside historical contexts,

it has become taboo in Western countries.

For example, the

German postwar criminal code makes the public showing of the Hakenkreuz (the swastika) and other Nazi symbols illegal and

punishable, except for scholarly reasons.

The powerful symbolism acquired by the swastika has often been

used in graphic design and propaganda as a means of drawing Nazi

comparisons; examples include the cover of Stuart Eizenstat's

2003 book Imperfect Justice, publicity materials for Costa-Gavras's

2002 film Amen, and a billboard that was erected opposite the

U.S. Interests Section in Havana, Cuba, in 2004, which

juxtaposed images of the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse pictures with

a swastika.

Founded in the 1970s, the Raelian Movement, a religious sect

believing in the possibility of immortality by scientific

progress, used a symbol that was the source of considerable

controversy: an interlaced Star of David and swastika. In 1991,

the symbol was changed to remove the swastika and deflect public

criticism.

The Society for Creative Anachronism, which aims to

study and recreate Medieval and Renaissance history, imposes

restrictions on its members' use of the swastika on their arms,

although some arms dating to the early days of the group have

the symbol.

Raelian Symbol

The Raëlian symbol, before 1991 and after recent years,

controversy has erupted when consumer goods bearing the symbol

have been exported (often unintentionally) to North America.

In

2002, Christmas crackers containing plastic toy pandas sporting

swastikas were pulled from shelves after complaints from

consumers in Canada, although the China-based manufacturer

claimed the symbol was presented in a traditional sense and not

as a reference to the Nazis.

In 1995, the City of Glendale, California scrambled to cover up

over 900 cast iron lampposts decorated with swastikas throughout

the downtown portion of the city; the lampposts had been

manufactured by an American company in the early 1920s, and had

nothing to do with Nazism.

In 2004, Microsoft released a "critical update" to remove two

swastikas and a Star of David from the font Bookshelf Symbol 7.

The font had been bundled with Microsoft Office 2003.

Punk rockers like Siouxsie Sioux, Sid Vicious and John Lydon

used, and were photographed using, the Nazi version of the

swastika for its shock value, notwithstanding that Malcolm

McLaren, the Sex Pistols' manager, was half-Jewish.

The previously successful career of the British band Kula Shaker

virtually collapsed in the 1990s after the band's frontman,

Crispian Mills, son of actress Hayley Mills, expressed his

desire to use Swastikas as part of the imagery of their live

show; because of this, and additional remarks he made, he was

widely accused of holding Nazi sympathies.

However, the band was musically influenced by Indian styles, and

Mills asserted that his attraction to the swastika was part of

an attempt to reclaim the Indian usage of the symbol in the

West.

In January 2005 there was much criticism when Prince Harry of

Wales, third in line of succession to the British throne, was

photographed wearing what appeared to be intended as an Afrika

Korps uniform, plus a Nazi swastika armband, to a fancy dress

party.

The Swastika

Stone

The stone overlooks the valley of the

River Wharfe, and is identical to some of the 'Camunnian Rose'

designs in Val Camonica, Italy - nine cup-marks in a cross shape,

surrounded by a curved swastika-shaped groove.

The Ilkley carving

also has an 'appendage' off the east arm - a cup surrounded by a

curved hook-shaped groove. It is unique on the moor (which is

covered in hundreds of cup-and-ring type carvings) although there is

an unfinished swastika design (more angular, without cups) on the

nearby Badger Stone.

One of the lines of cups on the Swastika Stone is less than a degree

off magnetic north-south.

One naturally looks north from the stone,

as it is on a rocky outcrop on the north side of the moor.

-

Was it

associated with the Pole Star with which its cups align?

-

Why then

does its shape describe a clockwise motion, whereas the stars turn

anti-clockwise around the pole?

Iron Age Rock Carving

The stone is found in the moors near Ilkley in West Yorkshire.

Perhaps the design relates to the shamanic practice of ascent up the

'Pillar of the World' (to use the Lapp term).

Numerous Siberian and

northern European peoples documented by Mircea Eliade see the Pole

Star as the summit of a pole holding up the sky (seen as a tent).

Eliade notes similar beliefs about the

Pole Star in Ancient Saxon, Scandinavian and Romanian myths. If,

then, one imagines the Swastika design to be the base of a Pillar of

the World, the implicit motion of the design makes sense. Something

that appears to turn anti-clockwise when looking up from the bottom

of a pole will, if it slides down the pole and is viewed from above,

appear to turn clockwise.

The Swastika Stone may map the turning sky down onto the ground,

forming the bond between 'levels' that is so central to shamanic

cosmology.

Also, the 'appendage' cup, in relation to the central cup, would

have only been a couple of degrees off the summer solstice sunrise

during the period 2000BCE - 100CE (covering most of the likely times

at which the glyph was carved. The 'hook' groove, if imagined to

turn with the swastika, would 'haul' the cup-sun across the sky.

This seems to strengthen the swastika-sky connection.

(I should note that I do not support the idea that cup-and-ring

patterns are maps of stellar constellations. Perhaps some involved

rudimentary attempts at this, but no one has found accurate

correspondences in any existing patterns. They seem to me to be more

generally concerned with access points to alternate realities).

With the Pole Star/Pillar of the World ideas in mind, one could see

some cup-and-ring markings as being related.

The 'tail' grooves

could be the Pillar reaching up to the cup-pole, surrounded by rings

of revolving stars. Some local cup-and-ring markings, like those on

the Panorama Stone, have 'ladders' instead of 'tail' grooves.

This

image further supports the shamanic interpretation of the petroglyphs, as ladders are among the most frequently occurring

representations of shamanic ascent to other worlds. Human figures

atop ladders appear in !Kung San rock art related to trance-state

ascension.

Cup-and-ring style petroglyphs in the British Isles are usually

dated to the Bronze Age (because some are included in, or in the

proximity of, Bronze Age burials) or the Neolithic (because of

comparable carvings on Irish passage graves from that period - see

also Richard Bradley's recent work 'Signing the Land' for arguments

dating this style of prehistoric art to the Neolithic).

The Swastika Stone is arguably associated with this style of rock

art, due to its use of cup-marks, but I have recently come to see it

as most likely originating in the Iron Age, or even during Roman

occupation. This is because of Verbeia, a Romano-Celtic goddess

revered by the Roman troops stationed in Ilkley (then Olicana).

Verbeia is often accepted as being a version of the Celtic

spring/fire goddess Brigid, who is still associated with

swastika-like symbols in Ireland. Also, the Roman cohort which set

up her altar were recruited from the Lingones, a Gaulish Celtic

tribe.

Apparently Romano-Celtic coins have been found in Gaul bearing

swastika-like designs. It seems tempting to think that the Lingones

cohort carved the Swastika Stone when they were here, but this would

surely be unusual.

Or perhaps the recruited Celtic/Roman troops were

influenced in their choice of 'genuis loci', Verbeia, by the native

Celts of West Yorkshire, the Brigantes (whose name derives from the

goddess Brigantia, related to Brigid), who may have already carved

the stone.

The Swastika may map the turning sky down onto the ground, forming

the bond between 'levels' that is so central to shamanic cosmology.

Spiritual

Secrets in the Carbon Atom - The Swastika

Legend has it that the Vedic

civilization was highly advanced.

The sages that oversaw its

development, through their mystic insight and deep meditation,

discovered the ancient symbols of spirituality - Aumkara and

Swastika. They also discovered many scientific principles

that they applied to develop a highly advanced technology.

They gave the atom its sanskrit name "Anu".

|