|

by Acharya S/D.M. Murdock

22 March 2012

from FreeThoughtNation Website

In the first edition of The Christ Conspiracy: The Greatest

Story Ever Sold (1999), I included a chapter entitled "The Bible,

Sex and Drugs", at the end of which I provided a line

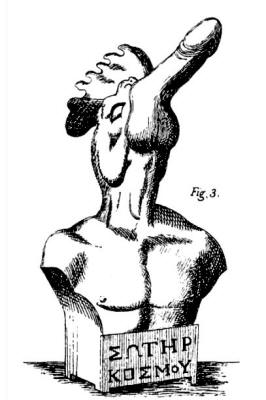

drawing of a bronze, rooster-headed bust with a phallus for a beak.

Under the image, I added the following caption:

Bronze sculpture hidden in the Vatican treasury of the Cock, symbol

of St. Peter. Inscription reads "Savior of the World."

I then cited the image as coming from "Walker, WDSSO," a reference

to Barbara G. Walker's

The Woman's Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred

Objects, included in my bibliography at the end of the book.

Previous to this image (168), I had discussed this theme of the

"peter" or cock, with the esoteric and "vulgar" meaning:

"Peter" is not only "the rock" but also "the cock" or penis, as the

word is used as slang to this day.

As Walker says,

"The cock was

also a symbol of Saint Peter, whose name also meant a phallus or

male principle (pater) and a phallic pillar (petra). Therefore, the

cock's image was often placed atop church towers."

The "Savior of the World" image appears in Walker's book on p. 397,

where she remarks:

It is no coincidence that "cock" is slang for "penis." The cock was

a phallic totem in Roman and medieval sculptures showing cocks

somehow transformed into, or supporting, human penises. Roman

carvings of disembodied phalli often gave them the legs or wings of

cocks.

Hidden in the treasury of the Vatican is a bronze image of a

cock with the head of a penis on the torso of a man, the pedestal

inscribed "The Savior of the World."

(There follows her quote cited in the paragraph above.)

Fabricated image or 'celebrated bronze'?

Over the years since The Christ Conspiracy was published, this image

has been the periodic focus of interest. Of late, in his new book

Did Jesus Exist?,

Bart Ehrman has raised up this image in my book

and appears to be accusing me of fabricating it.

Quoting me first,

he comments:

"'Peter' is not only 'the rock' but also 'the cock,' or penis, as

the word is use as slang to this day."

Here Acharya shows (her own?)

hand drawing of a man with a rooster head but with a large erect

penis instead of a nose, with this description:

"Bronze sculpture

hidden in the Vatican treasure [sic] of the Cock, symbol of St.

Peter" (295).

[There is no penis-nosed statue of Peter the cock in

the Vatican or anywhere else except in books like this, which love

to make things up.]

(The "treasure" typo is Ehrman's, while the "sic" is mine. The other

comments in brackets and parentheses are Ehrman's.)

In insinuating that I drew the image myself, Ehrman is indicating he

did not notice the citation under it in my book, clearly referring

to Barbara Walker's work.

He is further implying that I simply make

things up, and he is asserting with absolute certainty that no such

bronze has existed in the Vatican, essentially stating that I

fabricated the entire story.

Contrary to these unseemly accusations,

the facts are that I did not draw the image, the source of which was

cited, and that, according to several writers, the image certainly

is "hidden"

in the Vatican, as I stated.

In The Woman's Dictionary (397), Walker cites the image as "Knight,

pl. 2," which, in her bibliography, refers to: Knight, Richard

Payne - A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus. New York: University

Books, 1974.

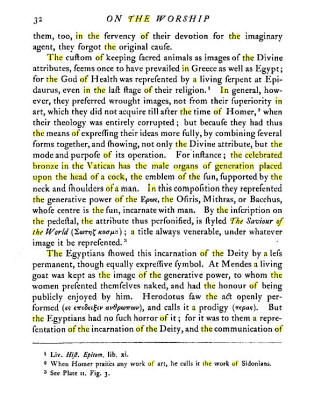

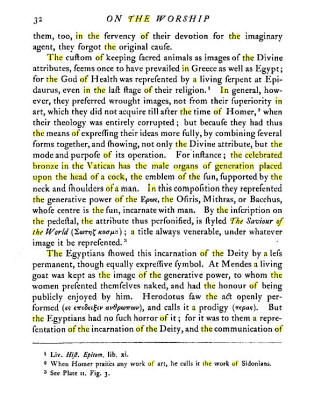

Consulting an earlier edition of Knight's book (1865

- above image), we find a

discussion of the object in question (32):

...the celebrated bronze in the Vatican has the male organs of

generation placed upon the head of a cock, the emblem of the sun,

supported by the neck and shoulders of a man.

In this composition

they represented the generative power of the Ερως [Eros], the

Osiris, Mithras, or Bacchus, whose centre is the sun.

By the

inscription on the pedestal, the attribute thus personified, is

styled The Savior of the World..., a title always venerable under

whatever image it be presented.

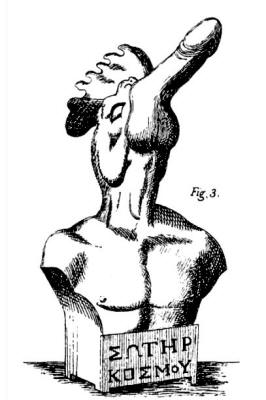

Here Knight references the image as "Plate II. Fig. 3."

Turning to

the back of the book, around p. 263, we find the image (above),

which is hand-drawn because of its age, printed when photography was

still not entirely feasible for publishers.

On page 35, Knight mentions the "celebrated bronze" again:

...Oftentimes, however, these mixed figures had a peculiar and

proper meaning, like that of the Vatican Bronze...

Another source, Gordon Williams in

A Dictionary of Sexual Language

and Imagery (258), comments about this artifact:

The relationship of cock and phallus is ancient. A bronze bust in

the Vatican Museum, bearing the Greek inscription "Redeemer of the

World" (Fuchs, Geschichte der Erotischen Kunst [Berlin 1908] fig.

103), is given a cock's head, the nose or beak being an erect penis.

Doing our scholarly due diligence, we find the pertinent figure in

Fuchs on p. 133.

Hot on the trail, we discover more information in

Peter Lang's Privatisierung der Triebe? (1994:203) about the,

"small

bust known as the Albani bronze, still housed in the Vatican's

secret collection..."

There, we read further:

"Its plinth is

inscribed 'Saviour of the World' in Greek, and it is possibly of

Gnostic import."

In another mention of the "notorious Albani bronze said to be held

in the Vatican Museum," we learn that such Rome phallic

representations are called priapi gallinacei. (Jones, Malcolm,

The

Secret Middle Ages, 75)

As we can see, this bronze image is

"celebrated" and "notorious," which means many scholars have written

about it, also stating that it is "housed" and "held" in the Vatican

Museum.

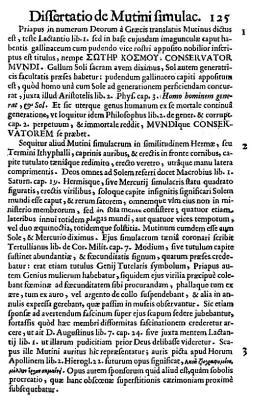

Romanum Museum, 1692

Continuing the hunt, a discussion of this artifact can be found in a

book entitled Public Characters of 1803-1804 (127), which comments

about the "Savior of the World" inscription, written in Greek as

ΣΩΤΗΡ ΚΟΣΜΟΥ, a phrase used also to describe

Jesus Christ:

That inscription is found upon an ancient Phallus, of a date of much

more remote antiquity than the birth of Christ. The account of this

antiquity may be seen at large in "De la Chaussee's Museum Romanum,"

printed at Rome, in folio, in 1692...

The late reverend and learned Dr. Middleton, in that valuable work

entitled "Germana quaedam antiquitatis eruditae monumenta, etc." has

not scrupled to give the following short account of it...

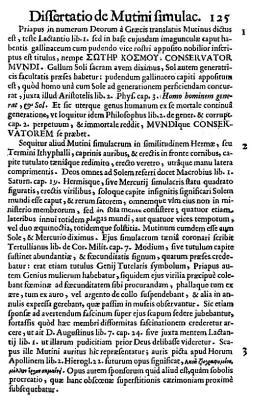

Tracing the image to De la Chaussee's Romanum Museum, we discover a

description on page 125 of volume 1:

The author follows this discussion with another about the ancient

author Macrobius and his work concerning the various gods of the

Roman Empire and their solar nature.

The priapus gallinaceus

A description of the statue in Latin is also provided by Rev. Dr.

Conyers Middleton (The Miscellaneous Works of the Late Reverend and

Learned Conyers Middleton, 4:51):

Quod quidem illustrari quodammodo videtur a Symbolica quadam apud

Causęum Priapi effigie, cui Galli Gallinacei caput crista ornatum,

rostri vero loco, Fascinum ingens datur: cujusque in basi litteris

Gręcis inscriptum legitur ΣΩΤΗΡ ΚΟΣΜΟΥ. Servator orbis. Quae omnia

vir doctus ita interpretatur:

"Gallum scilicet, avem soli sacram

esse; solemque generatricis facultatis pręsidem; pudendumque ideo

virile Gallinaceo capiti adjunctum denotare, quod a conjunctis solis

Priapique viribus, animalium genus omne procreatum et conservatum

sit, secundum physicum quoddam Aristotelis axioma, Homo hominem

general et Sol."

Here Middleton describes the "priapus effigy" as a rooster with a

head crest and the inscription "Savior of the World" or Servator

orbis in the Latin.

A "learned man" interprets the image as a cock,

a bird sacred to the sun, a symbol of fertility and generative

power. We can see where the term

priapus gallinaceus comes from, as

it refers to the erect member of the god

Priapus and the Latin word

for "rooster" or "cock."

Therefore, we are discussing an entire

genre of artifacts, evidently dating to before the common era and

into it (Gnostic?);

other such examples can be cited.

In The Image of Priapus (67), Giancarlo Carlobelli writes:

The "Soter cosmou" portrayed as the central figure appears to be an

example of what the classical scholars refer to as "Priapus

gallinaceus"; it may be a herm. The illustration had already

appeared in De la Chausse...

Here we learn that authors in antiquity used this term,

priapus

gallinaceus or "priapus cock."

Soter Cosmou - Savior of the World

Continuing our search, we find in Otto Augustus Wall's

Sex and Sex

Worship (Phallic Worship): A Scientific Treatise on Sex (437) a

photograph of what appears to be the original bronze statue (or at

least its twin).

Concerning this artifact, Wall (438) states that,

"this representation of a bronze figure of Priapus... was found in an

ancient Greek temple..."

Hidden in the Vatican

In

Studies in Iconography (7-8:94), published by Northern Kentucky

University, after discussing this "Savior of the World" artifact,

the author comments:

This object was published under papal and royal authority, exhibited

for a time in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and is now

said to be held inaccessible in the secret collections of the

Vatican.

During the public life of this bronze, officials disagreed

upon the probity of the exhibit. One offended cardinal requested

that the object be removed...

The writer (95) further states that,

"the Vatican Savior-as-Phallic-cock

was a scandalous satire on early Christians."

We are therefore

justified in bringing up this artifact and wondering why it would

serve as "satire on early Christians," if not for the reasons stated

here.

I obviously did not fabricate the image of this artifact, which has

been known in scholarly circles for over 300 years. Nor was my

contention erroneous that the figure is secreted in the Vatican,

according to several authors.

Nevertheless, Ehrman continues his imputation by concluding about my

book:

In short, if there is any conspiracy here, it is not on the part of

the ancient Christians who made up Jesus but on the part of modern

authors who make up stories about the ancient Christians and what

they believed about Jesus.

As we can see, everything in my book concerning this discussion is

cited and accurately represents the original commentary, as found in

several publications dating from the 17th century until the present

era, reflecting a tradition from antiquity.

It is unfortunate when

other scholars engage in libelous accusation and gross

misrepresentation, of which there are a number of other instances in Ehrman's book vis-ą-vis my work.

|