|

by Stephen Smith

September 25, 2011

from

Thunderbolts Website

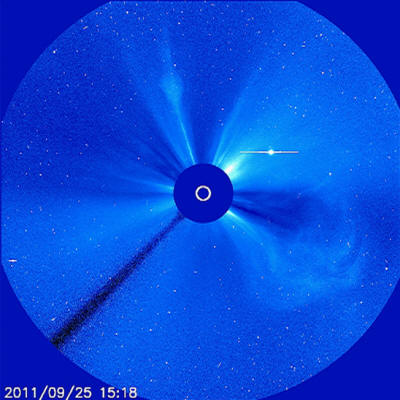

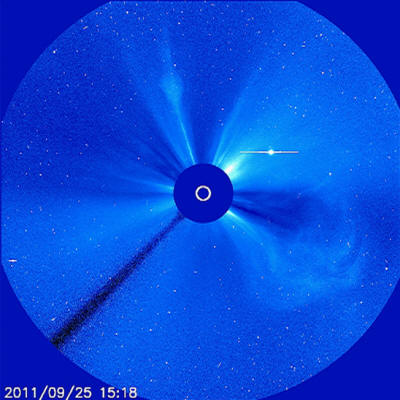

Latest image from the SOHO satellite. No sign of Comet Elenin.

Credit: NASA/ESA

Comet Elenin, despite fear mongers and

media hype, has vanished.

Leonid Elenin discovered C/2010 X1 (subsequently named after him) on

December 10, 2010. The comet reached perihelion on September 11,

2011 but does not seem to have survived its encounter with the Sun’s

electromagnetic fields.

Since the comet’s initial discovery, a litany of doom “prophecies”

has flooded the internet.

According to one report, over 12,000

websites have appeared with warnings of impending disaster or some

kind of world-changing “spiritual” event taking place either at

perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) or on September 23. Both

dates have come and gone, while our globe rolls on without any

effects.

If those who wish to use small comets as their theoretical tools of

destruction were to investigate their structure and behavior,

another way of interpreting what they are would bring an end to such

speculations. The first question to ask is: what is a comet? The

second question is: what effect can they have on Earth?

The commonly accepted view of comets is that they are the remains of

the original nebular cloud out of which our Solar System condensed.

Standard theory states that after the Sun, planets, moons, and planetesimals formed, a vast cloud of frozen water, dust, and gas

known as

the Oort Cloud was left in a halo around the Sun at a

distance of about 50,000 astronomical units (AU). In comparison,

Pluto is approximately 39 AU from the Sun.

An AU is almost 150

million kilometers, or the mean radius of Earth’s orbit.

As the theory goes, matter in the Oort Cloud has also condensed, but

into icy balls rather than rocky bodies. The Merriam-Webster

dictionary definition of a comet is:

“a celestial body that appears

as a fuzzy head usually surrounding a bright nucleus, that has a

usually highly eccentric orbit, that consists primarily of ice and

dust, and that often develops one or more long tails when near the

Sun.”

This conglomeration is often referred to as a “dirty snowball”

in consensus circles.

The

Giotto and

Deep Impact space probes told a different story,

however.

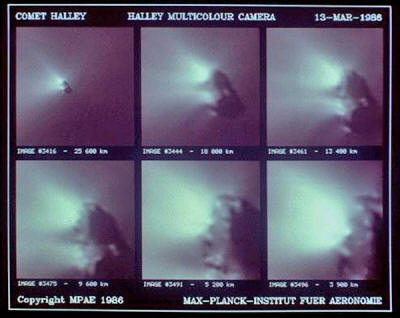

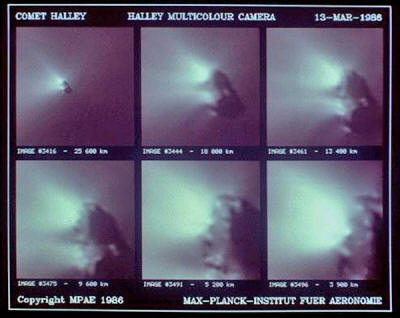

When Giotto made its close approach to Halley’s comet

(below image) in

1986, it sent back images that revealed the comet to be blackened

and scorched.

Indeed,

ESA scientists announced that it was the

blackest object ever discovered, even blacker than the soot-colored

moon

Phoebe.

Other comets have definitively falsified the dirty snowball

hypothesis. When

Shoemaker-Levy 9 exploded after passing near

Jupiter’s magnetosphere,

no volatile compounds were found, leaving

astronomers mystified.

When Deep Space 1, the first spacecraft with

an

ion propulsion drive, flew past comet Borrelly

(below image), the comet

appeared more like an asteroid, possessing a dry, hard surface: no

traces of ice or snowy fields.

Comets experience a steadily increasing voltage and current density

in the solar ‘wind’ as they race toward the Sun. This causes them to

acquire plasma sheaths as they move along, otherwise known as comas.

Some

cometary comas have been estimated to be more than a million

kilometers in diameter.

Eventually, the ‘dark discharge’ mode of the coma switches to the

‘arc mode,’ producing cathode jets and the characteristic comet dust

and ion tails. Close-up images of comet nuclei show bright spots on

the black nucleus, which may be explained as the arc touchdown

locations Unexpected X-rays have been detected coming from the

comet’s plasma sheath.

The energy required to generate X-rays is

supplied by the comet’s electrical discharge.

Comet Hyakutake is a

good example.

Comets are small. Most of them have a nucleus no more than 16

kilometers in diameter. They carry a negative charge with respect to

the Sun, so they begin to discharge violently when they approach the

inner Solar System.

However, their mass is low and their electric

fields are correspondingly weak when compared to Earth.

Mainstream viewpoints must come to realize that asteroids and comets

are not completely different from one another. The

Stardust mission

to

comet Wild 2 gathered samples from its coma, returning material

to Earth that resembled meteoric dust. Not what was expected from a

slushy mudball.

Comets do not initiate earthquakes, tsunamis, or volcanic eruptions

on our planet, especially when they are millions of kilometers away.

If they get close enough to penetrate Earth’s plasmasphere, they

most likely will blow up, just like Shoemaker-Levy 9 did.

|