|

by Lorraine Evans

from

CarlaNaylan Website

|

Kingdom of the Ark is a

work of narrative non-fiction, putting forward the

theory that refugees from Ancient Egypt settled in

Britain and/or Ireland in the middle of the Bronze Age,

under the leadership of Meritaten, eldest daughter of

the 'Heretic Pharaoh' Akhenaten. |

Medieval

legend

A medieval manuscript called the

Scotichronicon, or

Chronicles of the Scots, written in AD 1435 by a monk named

Walter Bower, gives the

following legend about the origin of the Scots:

"In ancient times Scota, the

daughter of pharaoh, left Egypt with her husband Gaythelos

by name and a large following. For they had heard of the

disasters which were going to come upon Egypt, and so through

the instructions of the gods they fled from certain plagues that

were to come. They took to the sea, entrusting themselves to the

guidance of the gods. After sailing in this way for many days

over the sea with troubled minds, they were finally glad to put

their boats in at a certain shore because of bad weather."

The manuscript goes on to say that the

Egyptians settled in what is now Scotland, were later chased

out by the local population and moved to Ireland, where they merged

with an Irish tribe and became known as the Scotti. They

became High Kings of Ireland, and eventually re-invaded and

re-conquered Scotland, which gains its name from their founding

princess, Scota.

This sort of folk etymology, deriving contemporary names from

(legendary?) eponymous founders, was extremely popular in the Middle

Ages. For example, Britain is supposed to have been named after

Brutus (Historia Brittonum), Gwynedd after a (legendary?)

king Cunedda, and the seven provinces of the Picts after the seven

sons of Cruithne.

Orkneyinga Saga, written in

Iceland in about 1200 AD, attributes the name of Norway to a

legendary founder called Nor, and Historia Brittonum,

written in northern Britain around 830 AD, attributes the names of

major European tribes (Franks, Goths, Alamans, Burgundians,

Longobards, Saxones, Vandals) to the sons of a descendant of

Noah.

Kingdom of the Ark attempts to find

evidence to support the story of Scota's journey from Egypt to

Britain or Ireland.

Egyptian

history

As Scota is not an Egyptian name, the first task for the

author is to identify a plausible candidate princess from surviving

Egyptian records. The Walter Bower manuscript gives the name

of Scota's father as Achencres, and a historian called

Manetho, writing around 300 BC, gives Achencres as the

Greek version of Akhenaten. As readers of the recent novel

Nefertiti will know, Akhenaten ruled in Egypt around 1350 BC and

instigated a political and religious revolution, moving the capital

to a new city at a site known today as Amarna and attempting to

change the religion of Egypt to sole worship of the sun-disk or Aten.

Six daughters of Akhenaten and his queen

Nefertiti are known from carvings in the royal palaces excavated at

Amarna. The author argues that five of the daughters appear to have

died in Egypt, and that the eldest daughter Meritaten

disappears from the records at around the time of Akhenaten's death

and met an unknown fate.

On the strength of this, she identifies

Meritaten as 'Scota'.

Akhenaten's reign was not a successful time for Egypt, and the end

of his reign appears to have resulted in a period of political

chaos. He was followed by three short-lived successors (including

Tutankhamun of the famous tomb), and then by a military Pharaoh

Horemheb, who came to power about 1320 BC. Horemheb appears to have

had a particular dislike of everything associated with Akhenaten,

and systematically destroyed buildings and monuments erected in

Akhenaten's reign.

Given this upheaval, it is not

implausible that a daughter of Akhenaten might have had good reason

to become a political refugee and look for a new life outside Egypt,

perhaps with a foreign husband. Several chapters in Kingdom of

the Ark are devoted to Akhenaten's chaotic reign and its

aftermath, and are among the most detailed and informative in the

book (probably reflecting the author's background as an

Egyptologist).

Having suggested that Scota might be an alternative name for

Meritaten, the author then looks for evidence that Meritaten/Scota

travelled from Egypt to Britain and/or Ireland as recounted in the

Walter Bower manuscript.

This relies mainly on material from a

range of archaeological sources, summarized below.

Archaeology

A necklace of amber, jet and faience beads was found with a

secondary Bronze Age burial of a young man in a Neolithic burial

mound at Tara in Ireland, excavated in 1955 and carbon-dated to 1350

BC. The faience beads were similar to those in the tomb of

Tutankhamun, which dates to about the same period. (Note:

faience is a ceramic, often characterized by a glossy blue glaze

resembling precious stones such as turquoise or lapis lazuli).

A second, similar, necklace was found in

a Bronze Age burial mound in Devon in 1889. As the faience beads are

similar to those found in Egypt at the same period, the author

suggests that the burials may have been high-ranking Egyptians.

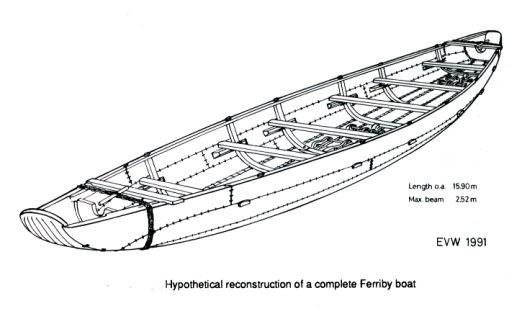

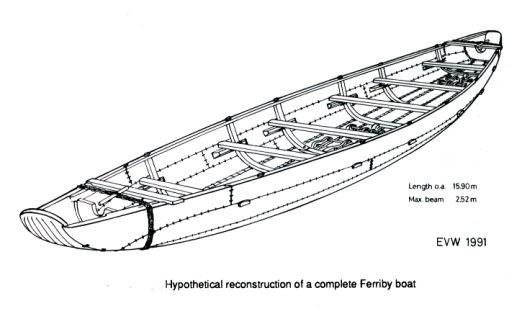

A shipwrecked boat excavated in Ferriby on the Humber Estuary

in northern England in 1938-1946 was of a design similar to those

used in the ancient Mediterranean and was carbon-dated to 1400-1350

BC. The author suggests that the boat may have been part of Scota's

fleet from Egypt.

Amber from the Baltic Sea is found in

Bronze Age contexts in Britain and in Mycenae (Greece), indicating

the existence of long-distance trading routes across Europe. The

amber's source can be identified by infrared analysis.

Egyptian artifacts such as faience are found in Mycenaean

excavations, and Mycenean-style pottery is found in Akhenaten's city

of Amarna in Egypt, indicating trading and/or diplomatic links

between Mycenae and Akhenaten's Egypt. The author suggests that

Akehenaten's daughter Meritaten could have known about

north-western Europe via contacts with Mycenae.

There are mysterious prehistoric towers called

motillas in

Spain, which consist of a conical tower in an enclosure.

One was excavated in 1947 and metalwork dated to the middle Bronze

Age was found.

The Bower chronicle says that the

followers of Scota settled for a while in Spain and built,

"….a very strong tower, encircled by

deep ditches, in the middle of the settlement….", and the author

suggests that the motillas are these towers.

Motilla sites - Spain

Numerous Egyptian artifacts have been

found in Spain, dating from the Third Dynasty (well before the time

of Akhenaten and the supposed flight of Meritaten),

indicating long-established links between Egypt and Spain.

(However, as far as I can see the author does not claim that

Egyptian artifacts have been found at motilla sites).

Two barrow burials near Stonehenge in Britain were excavated in 1808

and 1818 and contained amber jewellery and gold artifacts that

resemble types found in the eastern Mediterranean.

Tin ingots have been found in Cornwall that resemble those found in

the eastern Mediterranean. The author suggests that Cornish tin may

have been traded, probably by the Phoenicians, into the

Mediterranean in the Bronze Age, but notes that it cannot be proved

because the Cornish ingots cannot be dated.

Two Bronze Age shipwrecks found in the English Channel, one near

Dover and one in Devon, date to about 1200 BC and appear to have

been carrying cargoes of bronze artifacts of types found in

Continental Europe, indicating that seaborne trade between Britain

and Europe occurred in the Bronze Age.

Summary and

conclusion

To my mind, the archaeological finds described in the book make a

reasonably convincing case for trade links across Europe in the

Bronze Age, connecting Ireland, Britain and the Baltic with central

Europe, Spain, the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt.

If the boats

found at Ferriby did indeed come from the eastern Mediterranean,

some of this trade may have been direct rather than the passage of

goods through a sequence of intermediaries.

This doesn't particularly surprise me;

ancient cultures have a habit of turning out to be more mobile, more

connected and more sophisticated than we thought. I would have liked

to see some attempt to set the finds in context. As presented, they

indicate that long-distance trade was possible, but give little idea

of whether it was rare or commonplace.

I'm afraid I'm less convinced that these links can be construed as

'evidence' of a single person's journey from Egypt to Ireland and/or

Britain, and still less that they constitute proof that a daughter

of an Egyptian Pharaoh founded the dynasty of the High Kings of

Tara and gave her name to Scotland. It could have

happened (and it would make a great starting point for a novel), but

it seems to me that the artifacts do not demand an explanation

involving a refugee Egyptian princess.

They

can be just as easily, and more simply, explained as the result of

regular trading and/or diplomatic links over a considerable period. They

can be just as easily, and more simply, explained as the result of

regular trading and/or diplomatic links over a considerable period.

Kingdom of the Ark presents an intriguing hypothesis, but in

my view has a tendency to over-interpret its evidence. For example,

the book claims that the

Walter Bower manuscript had

preserved accurate details that were only later discovered by

archaeology, such as "the exact dimensions" of the towers in Spain

and the "terrible plagues" in Akhenaten's Egypt.

Yet the actual wording of the Bower

manuscript - taking the translations given in the book - seem to me

to be too unspecific to support this claim.

Bower's description of

the Spanish settlement is,

"….a very strong tower, encircled by

deep ditches, in the middle of the settlement….".

This is a general description, not a set

of exact dimensions.

It could also apply to a medieval castle in the

middle of a fortified town, for example - which would presumably

have been familiar to Bower. And Bower specifically says that Scota

fled "…from plagues that were to come," whereas the plagues

documented at Amarna happened before Meritaten disappeared from the

records - i.e., Bower would seem to have got the events the opposite

way round.

He may have been drawing on a genuine

tradition (although it's worth noting that 1350 BC to 1435 AD is

over 2,700 years, which is a very long time to maintain a

tradition), but I think it is stretching a point to claim accuracy.

There are also occasional oddities in editing, e.g. "These are found

on the Continent, predominantly in southern Germany to the west of

the River Seine."

The famous River Seine is in France. Is

there another one in Germany, or is this an error? Kingdom of the

Ark presents its case with a strong narrative drive that carries the

reader easily along, but needs to be read with a critical mind.

A colorful narrative full of interesting snippets of history and

archaeology, presenting an intriguing (though to my mind not

entirely convincing) theory.

References

|