WE, come now to the theory which is at present most generally accepted:

It being apparent that glaciers were not adequate to produce the results which we find, the glacialists have fallen back upon an extraordinary hypothesis--to wit, that the whole north and south regions of the globe, extending from the poles to 35° or 40° of north and south latitude, were, in the Drift age, covered with enormous, continuous sheets of ice, from one mile thick at its southern margin, to three or five miles thick at the poles. As they find drift-scratches upon the tops of mountains in Europe three to four thousand feet high, and in New England upon elevations six thousand feet high, it follows, according to this hypothesis, that the ice-sheet must have been considerably higher than these mountains, for the ice must have been thick enough to cover their tops, and high enough and heavy enough above their tops to press down upon and groove and scratch the rocks. And as the striæ in Northern Europe were found to disregard the conformation of the continent and the islands of the sea, it became necessary to suppose that this polar ice-sheet filled up the bays and seas, so that one could have passed dry-shod, in that period, from France to the north pole, over a steadily ascending plane of ice.

No attempt has been made to explain where all this

{p. 24}

ice came from; or what force lifted the moisture into the air which, afterward descending, constituted these world-cloaks of frozen water.

It is, perhaps, easy to suppose that such world-cloaks might have existed; we can imagine the water of the seas falling on the continents, and freezing as it fell, until, in the course of ages, it constituted such gigantic ice-sheets; but something more than this is needed. This does not account for these hundreds of feet of clay, bowlders, and gravel.

But it is supposed that these were torn from the surface of the rocks by the pressure of the ice-sheet moving southward. But what would make it move southward? We know that some of our mountains are covered to-day with immense sheets of ice, hundreds and thousands of feet in thickness. Do these descend upon the flat country? No; they lie there and melt, and are renewed, kept in equipoise by the contending forces of heat and cold.

Why should the ice-sheet move southward? Because, say the "glacialists," the lands of the northern parts of Europe and America were then elevated fifteen hundred feet higher than at present, and this gave the ice a sufficient descent. But what became of that elevation afterward? Why, it went down again. It had accommodatingly performed its function, and then the land resumed its old place!

But did the land rise up in this extraordinary fashion? Croll says:

"The greater elevation of the land (in the Ice period) is simply assumed as an hypothesis to account for the cold. The facts of geology, however, are fast establishing the opposite conclusion, viz., that when the country was covered with ice, the land stood in relation to the sea at a lower level than at present, and that the continental periods or times, when the land stood in relation to the

{p. 25}

sea at a higher level than now, were the warm inter-glacial periods, when the country was free of snow and ice, And a mild and equable condition of climate prevailed. This is the conclusion toward which we are being led by the more recent revelations of surface-geology, and also by certain facts connected with the geographical distribution of plants and animals during the Glacial epoch."[1]

H. B. Norton says:

"When we come to study the cause of these phenomena, we find many perplexing and contradictory theories in the field. A favorite one is that of vertical elevation. But it seems impossible to admit that the circle inclosed within the parallel of 40°--some seven thousand miles in diameter--could have been elevated to such a height as to produce this remarkable result. This would be a supposition hard to reconcile with the present proportion of land and water on the surface of the globe and with the phenomena of terrestrial contraction and gravitation."[2]

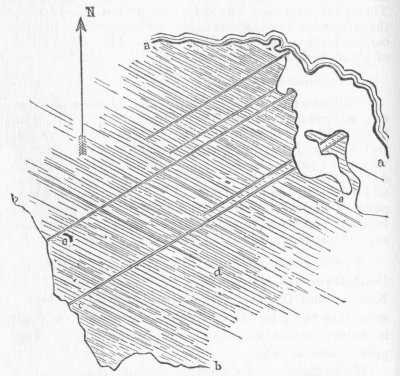

We have seen that the surface-rocks underneath the Drift are scored and grooved by some external force. Now we find that these markings do not all run in the same direction; on the contrary, they cross each other in an extraordinary manner. The cut on the following page illustrates this.

If the direction of the motion of the ice-sheets, which caused these markings, was,--as the glacialists allege,--always from the elevated region in the north to the lower ground in the south, then the markings must always have been in the same direction: given a fixed cause, we must have always a fixed result. We shall see, as we go on in this argument, that the deposition of the "till" was instantaneous; and, as these markings were made before or at the same time the "till" was laid down, how could the land

[1. "Climate and Time," p. 391.

2. "Popular Science Monthly," October, 1879, p. 833.]

{p. 26}

possibly have bobbed up and down, now here, now there, so that the elevation from which the ice-sheet descended

SKETCH OF GLACIER-FURROWS AND SCRATCHES AT STONY POINT, LAKE ERIE, MICHIGAN.

aa, deep water-line; bb border of the bank of earthy materials; cc, deep parallel grooves four and a half feet apart and twenty-five feet long, bearing north 60° east; d, a set of grooves and scratches bearing north 60° west; e, a natural bridge.

[Winchell's "Sketches of Creation," p. 213.]

was one moment in the northeast, and the next moment had whirled away into the northwest? As the poet says:

". . . Will these trees,

That have outlived the eagle, page thy steps

And skip, when thou point'st out?"

{p. 27}

But if the point of elevation was whisked away from east to west, how could an ice-sheet a mile thick instantaneously adapt itself to the change? For all these markings took place in the interval between the time when the external force, whatever it was, struck the rocks, and the time when a sufficient body of "till" had been laid down to shield the rocks and prevent further wear and tear. Neither is it possible to suppose an ice-sheet, a mile in thickness, moving in two diametrically opposite directions at the same time.

Again: the ice-sheet theory requires an elevation in the north and a descent southwardly; and it is this descent southwardly which is supposed to have given the momentum and movement by which the weight of the superincumbent mass of ice tore up, plowed up, ground up, and smashed up the face of the surface-rocks, and thus formed the Drift and made the striæ.

But, unfortunately, when we come to apply this theory to the facts, we find that it is the north sides of the hills and mountains that are striated, while the south sides have gone scot-free! Surely, if weight and motion made the Drift, then the groovings, caused by weight and motion, must have been more distinct upon a declivity than upon an ascent. The school-boy toils patiently and slowly up the hill with his sled, but when he descends he comes down with railroad-speed, scattering the snow before him in all directions. But here we have a school-boy that tears and scatters things going up-hill, and sneaks down-hill snail-fashion.

"Professor Hitchcock remarks, that Mount Monadnock, New Hampshire, 3,250 feet high, is scarified from top to bottom on its northern side and western side, but not on, the southern."[1]

This state of things is universal in North America.

[1. Dana's "Manual of Geology," p. 537.]

{p. 28}

But let us look at another point:

If the vast deposits of sand, gravel, clay, and bowlders, which are found in Europe and America, were placed there by a great continental ice-sheet, reaching down from the north pole to latitude 35° or 40°; if it was the ice that tore and scraped up the face of the rocks and rolled the stones and striated them, and left them in great sheets and heaps all over the land--then it follows, as a matter of course, that in all the regions equally near the pole, and equally cold in climate, the ice must have formed a similar sheet, and in like manner have torn up the rocks and ground them into gravel and clay. This conclusion is irresistible. If the cold of the north caused the ice, and the ice caused the Drift, then in all the cold north-lands there must have been ice, and consequently there ought to have been Drift. If we can find, therefore, any extensive cold region of the earth where the Drift is not, then we can not escape the conclusion that the cold and the ice did not make the Drift.

Let us see: One of the coldest regions of the earth is Siberia. It is a vast tract reaching to the Arctic Circle; it is the north part of the Continent of Asia; it is intersected by great mountain-ranges. Here, if anywhere, we should find the Drift; here, if anywhere, was the ice-field, "the sea of ice." It is more elevated and more mountainous than the interior of North America where the drift-deposits are extensive; it is nearer the pole than New York and Illinois, covered as these are with hundreds of feet of débris, and yet there is no Drift in Siberia!

I quote from a high authority, and a firm believer in the theory that glaciers or ice-sheets caused the drift; James Geikie says:

"It is remarkable that nowhere in the great plains of Siberia do any traces of glacial action appear to have

{p. 29}

been observed. If cones and mounds of gravel and great erratics like those that sprinkle so wide an area in Northern America and Northern Europe had occurred, they would hardly have failed to arrest the attention of explorers. Middendorff does, indeed, mention the occurrence of trains of large erratics which he observed along the banks of some of the rivers, but these, he has no doubt, were carried down by river-ice. The general character of the 'tundras' is that of wide, flat plains, covered for the most part with a grassy and mossy vegetation, but here and there bare and sandy. Frequently nothing intervenes to break the monotony of the landscape. . . . It would appear, then, that ill Northern Asia representatives of the glacial deposits which are met with in similar latitudes in Europe and America do not occur. The northern drift of Russia and Germany; the åsar of Sweden; the kames, eskers, and erratics of Britain; and the iceberg-drift of Northern America have, apparently, no equivalent in Siberia. Consequently we find the great river-deposits, with their mammalian remains, which tell of a milder climate than now obtains in those high latitudes, still lying undisturbed at the surface."[1]

Think of the significance of all this. There is no Drift in Siberia; no "till," no "bowlder-clay," no stratified masses of gravel, sand, and stones. There was, then, no Drift age in all Northern Asia, up to the Arctic Circle!

How pregnant is this admission. It demolishes at one blow the whole theory that the Drift came of the ice. For surely if we could expect to find ice, during the so-called Glacial age, anywhere on the face of our planet, it would be in Siberia. But, if there was an ice-sheet there, it did not grind up the rocks; it did not striate them; it did not roll the fragments into bowlders and pebbles; it rested so quietly on the face of the land that, as Geikie tells us, the pre-glacial deposits throughout Siberia, with their mammalian remains, are still found "lying undisturbed

[1. "The Great Ice Age," p. 460, published in 1873.]

{p. 30}

on the surface"; and he even thinks that the great mammals, the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros, "may have survived in Northern Asia down to a comparatively recent date,"[1] ages after they were crushed out of existence by the Drift of Europe and America.

Mr. Geikie seeks to account for this extraordinary state of things by supposing that the climate of Siberia was, during the Glacial age, too dry to furnish snow to make the ice-sheet. But when it is remembered that there was moisture enough, we are told, in Northern Europe and America at that time to form a layer of ice from one to three miles in thickness, it would certainly seem that enough ought to have blown across the eastern line of European Russia to give Siberia a fair share of ice and Drift. The explanation is more extraordinary than the thing it explains. One third of the water of all the oceans must have been carried up, and was circulating around in the air, to descend upon the earth in rain and snow, and yet none of it fell on Northern Asia! And as the line of the continents separating Europe and Asia had not yet been established, it can not be supposed that the Drift ref used to enter Asia out of respect to the geographical lines.

But not alone is the Drift absent from Siberia, and, probably, all Asia; it does not extend even over all Europe. Louis Figuier says that the traces of glacial action "are observed in all the north of Europe, in Russia, Iceland, Norway, Prussia, the British Islands, part of Germany in the north, and even in some parts of the south of Spain."[2] M. Edouard Collomb finds only a "a shred" of the glacial evidences in France, and thinks they were absent from part of Russia!

[1. "The Great Ice Age," p. 461.

2. "The World before the Deluge," p. 451.]

{p. 31}

And, even in North America, the Drift is not found everywhere. There is a remarkable region, embracing a large area in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota, which Professor J. D. Whitney[1] calls "the driftless region," in which no drift, no clays, no gravel, no rock strive or furrows are found. The rock-surfaces have not been ground down and polished. "This is the more remarkable," says Geikie, "seeing that the regions to the north, west, east, and south are all more or less deeply covered with drift-deposits."[2] And, in this region, as in Siberia, the remains of the large, extinct mammalia are found imbedded in the surface-wash, or in cracks or crevices of the limestone.

If the Drift of North America was due to the ice-sheet, why is there no drift-deposit in "the driftless region" of the Northwestern States of America? Surely this region must have been as cold as Illinois, Ohio, etc. It is now the coldest part of the Union. Why should the ice have left this oasis, and refused to form on it? Or why, if it did form on it, did it refuse to tear up the rock-surfaces and form Drift?

Again, no traces of northern drift are found in California, which is surrounded by high mountains, in some of which fragments of glaciers are found even to this day.[3]

According to Foster, the Drift did not extend to Oregon; and, in the opinion of some, it does not reach much beyond the western boundary of Iowa.

Nor can it be supposed that the driftless regions of Siberia, Northwestern America, and the Pacific coast are due to the absence of ice upon them during the Glacial

[1. "Report of the Geological Survey of Wisconsin," vol. i, p. 114.

2. "The Great Ice Age," p. 465.

3. Whitney, "Proceedings of the California Academy of Natural Sciences."]

{p. 32}

age, for in Siberia the remains of the great mammalia, the mammoth, the woolly rhinoceros, the bison, and the horse, are found to this day imbedded in great masses of ice, which, as we shall see, are supposed to have been formed around them at the very coming of the Drift age.

But there is another difficulty:

Let us suppose that on all the continents an ice-belt came down from the north and south poles to 35° or 40° of latitude, and there stood, massive and terrible, like the ice-sheet of Greenland, frowning over the remnant of the world, and giving out continually fogs, snow-storms, and tempests; what, under such circumstances, must have been the climatic conditions of the narrow belt of land which these ice-sheets did not cover?

Louis Figuier says:

"Such masses of ice could only have covered the earth when the temperature of the air was lowered at least some degrees below zero. But organic life is incompatible with such a temperature; and to this cause must we attribute the disappearance of certain species of animals and plants--in particular the rhinoceros and the elephant--which, before this sudden and extraordinary cooling of the globe, appeared to have limited themselves, in immense herds, to Northern Europe, and chiefly to Siberia, where their remains have been found in such prodigious quantities."[1]

But if the now temperate region of Europe and America was subject to a degree of cold great enough to destroy these huge animals, then there could not have been a tropical climate anywhere on the globe. If the line of 35° or 40°, north and south, was several degrees below zero, the equator must have been at least below the frost-point. And, if so, how can we account for the survival,

[1. "The World before the Deluge," p. 462.]

{p. 33}

to our own time, of innumerable tropical plants that can not stand for one instant the breath of frost, and whose fossilized remains are found in the rocks prior to the Drift? As they lived through the Glacial age, it could not have been a period of great and intense cold. And this conclusion is in accordance with the results of the latest researches of the scientists:--

"In his valuable studies upon the diluvial flora, Count Gaston de Saporta concludes that the climate in this period was marked rather by extreme moisture than extreme cold."

Again: where did the clay, which is deposited in such gigantic masses, hundreds of feet thick, over the continents, come from? We have seen (p. 18, ante) that, according to Mr. Dawkins, "no such clay has been proved to have been formed, either in the Arctic regions, whence the ice-sheet has retreated, or in the districts forsaken by the glaciers."

If the Arctic ice-sheet does not create such a clay now, why did it create it centuries ago on the plains of England or Illinois?

The other day I traveled from Minnesota to Cape May, on the shore of the Atlantic, a distance of about fifteen hundred miles. At scarcely any point was I out of sight of the red clay and gravel of the Drift: it loomed up amid the beach-sands of New Jersey; it was laid bare by railroad-cuts in the plains of New York and Pennsylvania; it covered the highest tops of the Alleghanies at Altoona; the farmers of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin were raising crops upon it; it was everywhere. If one had laid down a handful of the Wisconsin Drift alongside of a handful of the New Jersey deposit, he could scarcely have perceived any difference between them.

{p. 34}

Here, then, is a geological formation, almost identical in character, fifteen hundred miles long from east to west, and reaching through the whole length of North and South America, from the Arctic Circle to Patagonia.

Did ice grind this out of the granite?

Where did it get the granite? The granite reaches the surface only in limited areas; as a rule, it is buried many miles in depth under the sedimentary rocks.

How did the ice pick out its materials so as to grind nothing but granite?

This deposit overlies limestone and sandstone. The ice-sheet rested upon them. Why were they not ground up with the granite? Did the ice intelligently pick out a particular kind of rock, and that the hardest of them all?

But here is another marvel--this clay is red. The red is due to the grinding up of mica and hornblende. Granite is composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica. In syenitic granite the materials are quartz, feldspar, and hornblende. Mica and hornblende contain considerable oxide of iron, while feldspar has none. When mica and hornblende are ground up, the result is blue or red clays, as the oxidation of the iron turns the clay red; while the clay made of feldspar is light yellow or white.

Now, then, not only did the ice-sheet select for grinding the granite rocks, and refuse to touch the others, but it put the granite itself through some mysterious process by which it separated the feldspar from the mica and hornblende, and manufactured a white or yellow clay out of the one, which it deposited in great sheets by itself, as west of the Mississippi; while it ground up the mica and hornblende and made blue or red clays, which it laid down elsewhere, as the red clays are spread over that great stretch of fifteen hundred miles to which I have referred.

{p. 35}

Can any one suppose that ice could so discriminate?

And if it by any means effected this separation of the particles of granite, indissolubly knit together, how could it perpetuate that separation while moving over the land, crushing all beneath and before it, and leave it on the face of the earth free from commixture with the surface rocks?

Again: the ice-sheets which now exist in the remote north do not move with a constant and regular motion southward, grinding up the rocks as they go. A recent writer, describing the appearance of things in Greenland, says:

"The coasts are deeply indented with numerous bays and fiords or firths, which, when traced inland, are almost invariably found to terminate against glaciers. Thick ice frequently appears, too, crowning the exposed sea-cliffs, from the edges of which it droops in thick, tongue-like, and stalactitic projections, until its own weight forces it to break away and topple down the precipices into the sea."[1]

This does not represent an ice-sheet moving down continuously from the high grounds and tearing up the rocks. It rather breaks off like great icicles from the caves of a house.

Again: the ice-sheets to-day do not striate or groove the rocks over which they move.

Mr. Campbell, author of two works in defense of the iceberg theory--"Fire and Frost," and "A Short American Tramp"--went, in 1864, to the coasts of Labrador, the Strait of Belle Isle, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence, for the express purpose of witnessing the effects of icebergs, and testing the theory he had formed. On the coast of Labrador he reports that at Hanly Harbor, where

[1. "Popular Science Monthly," April, 1874, p. 646.]

{p. 36}

the whole strait is blocked up with ice each winter, and the great mass swung bodily up and down, "grating along the bottom at all depths," he "found the rocks ground smooth, but not striated."[1] At Cape Charles and Battle Harbor, he reports, "the rocks at the water-line are not striated."[2] At St. Francis Harbor, "the water-line is much rubbed smooth, but not striated."[3] At Sea Islands, he says, "No striæ are to be seen at the land-wash in these sounds or on open sea-coasts near the present waterline."[4]

Again: if these drift-deposits, these vast accumulations of sand, clay, gravel, and bowlders, were caused by a great continental ice-sheet scraping and tearing the rocks on which it rested, and constantly moving toward the sun, then not only would we find, as I have suggested in the case of glaciers, the accumulated masses of rubbish piled up in great windrows or ridges along the lines where the face of the ice-sheet melted, but we would naturally expect that the farther north we went the less we would find of these materials; in other words, that the ice, advancing southwardly, would sweep the north clear of débris to pile it up in the more southern regions. But this is far from being the case. On the contrary, the great masses of the Drift extend as far north as the land itself. In the remote, barren grounds of North America, we are told by various travelers who have visited those regions, "sand-hills and erratics appear to be as common as in the countries farther south."[5] Captain Bach tells us[6] that he saw great chains of sand-hills, stretching

[1. "A Short American Tramp," pp. 68, 107.

2. Ibid., p. 68.

3. Ibid., p. 72.

4. Ibid., p. 76.

5. "The Great Ice Age," p. 391.

6. "Narrative of Arctic Land Expedition to the Mouth of the Great Fish River," pp. 140, 346.]

{p. 37}

away from each side of the valley of the Great Fish River, in north latitude 66°, of great height, and crowned with gigantic bowlders.

Why did not the advancing ice-sheet drive these deposits southward over the plains of the United States? Can we conceive of a force that was powerful enough to grind up the solid rocks, and yet was not able to remove its own débris?

But there is still another reason which ought to satisfy us, once for all, that the drift-deposits were not due to the pressure of a great continental ice-sheet. It is this:

If the presence of the Drift proves that the country in which it is found was once covered with a body of ice thick and heavy enough by its pressure and weight to grind up the surface-rocks into clay, sand, gravel, and bowlders, then the tropical regions of the world must have been covered with such a great ice-sheet, upon the very equator; for Agassiz found in Brazil a vast sheet of "ferruginous clay with pebbles," which covers the whole country, "a sheet of drift," says Agassiz, "consisting of the same homogeneous, unstratified paste, and containing loose materials of all sorts and sizes," deep red in color, and distributed, as in the north, in uneven hills, while sometimes it is reduced to a thin deposit. It is recent in time, although overlying rocks ancient geologically. Agassiz had no doubt whatever that it was of glacial origin.

Professor Hartt, who accompanied Professor Agassiz in his South American travels, and published a valuable work called "The Geology of Brazil," describes drift-deposits as covering the province of Pará, Brazil, upon the equator itself. The whole valley of the Amazon is covered with stratified and unstratified and unfossiliferous

{p. 38}

Drift,[1] and also with a peculiar drift-clay (argile plastique bigarrée), plastic and streaked.

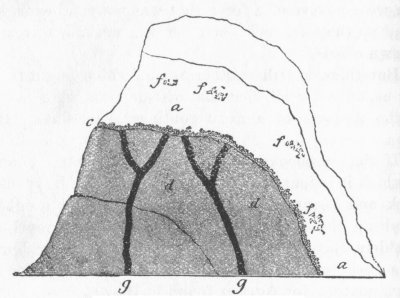

Professor Hartt gives a cut from which I copy the following representation of drift-clay and pebbles overlying a gneiss hillock of the Serra do Mar, Brazil:

DRIFT-DEPOSITS IN THE TROPICS.

a, drift-clay; f f, angular fragments of quartz; c. sheet of pebbles; d d, gneiss in situ; g g, quartz and granite veins traversing the gneiss.

But here is the dilemma to which the glacialists are reduced: If an ice-sheet a mile in thickness, or even one hundred feet in thickness, was necessary to produce the Drift, and if it covered the equatorial regions of Brazil, then there is no reason why the same climatic conditions should not have produced the same results in Africa and Asia; and the result would be that the entire globe, from pole to pole, must have rolled for days, years, or centuries, wrapped in a continuous easing, mantle, or shroud of ice, under which all vegetable and animal life must have utterly perished.

[1. "Geology of Brazil," p. 488.]

{p. 39}

And we are not without evidences that the drift-deposits are found in Africa. We know that they extend in Europe to the Mediterranean. The "Journal of the Geographical Society" (British) has a paper by George Man, F. G. S., on the geology of Morocco, in which he says:

"Glacial moraines may be seen on this range nearly eight thousand feet above the sea, forming gigantic ridges and mounds of porphyritic blocks, in some places damming up the ravines, and at the foot of Atlas are enormous mounds of bowlders."

These mounds oftentimes rise two thousand feet above the level of the plain, and, according to Mr. Man, were produced by glaciers.

We shall see, hereafter, that the sands bordering Egypt belong to the Drift age. The diamond-bearing gravels of South Africa extend to within twenty-two degrees of the equator.

It is even a question whether that great desolate land, the Desert of Sahara, covering a third of the Continent of Africa, is not the direct result of this signal catastrophe. Henry W. Haynes tells us that drift-deposits are found in the Desert of Sahara, and that--

"In the bottoms of the dry ravines, or wadys, which pierce the hills that bound the valley of the Nile, I have found numerous specimens of flint axes of the type of St. Acheul, which have been adjudged to be true palæolithic implements by some of the most eminent cultivators of prehistoric science."[1]

The sand and gravel of Sahara are underlaid by a deposit of clay.

Bayard Taylor describes in the center of Africa

[1. "The Palæolithic Implements of the Valley of the Delaware," Cambridge, 1881.]

{p. 40}

great plains of coarse gravel, dotted with gray granite bowlders.[1]

In the United States Professor Winchell shows that the drift-deposits extend to the Gulf of Mexico. At Jackson, in Southern Alabama, be found deposits of pebbles one hundred feet in thickness.[2]

If there are no drift-deposits except where the great ice-sheet ground them out of the rocks, then a shroud of death once wrapped the entire globe, and all life ceased.

But we know that all life,--vegetable, animal, and human,--is derived from pre-glacial sources; therefore animal, vegetable, and human life did not perish in the Drift age; therefore an ice-sheet did not wrap the world in its death-pall; therefore the drift-deposits of the tropics were not due to an ice-sheet; therefore the drift-deposits of the rest of the world were not due to ice-sheets: therefore we must look elsewhere for their origin.

There is no escaping these conclusions. Agassiz himself says, describing the Glacial age:

"All the springs were dried up; the rivers ceased to flow. To the movements of a numerous and animated creation succeeded the silence of death."

If the verdure was covered with ice a mile in thickness, all animals that lived on vegetation of any kind must have perished; consequently, all carnivores which lived on these must have ceased to exist; and man himself, without animal or vegetable food, must have disappeared for ever.

A writer, describing Greenland wrapped in such an ice-sheet, says

[1. "Travels in Africa," p. 188.

2. "Sketches of Creation," pp. 222, 223.]

{p. 41}

"The whole interior seems to be buried beneath a great depth of snow and ice, which loads up the valleys and wraps over the hills. The scene opening to view in the interior is desolate in the extreme--nothing but one dead, dreary expanse of white, so far as the eye can reach--no living creature frequents this wilderness--neither bird, beast, nor insect. The silence, deep as death, is broken only when the roaring storm arises to sweep before it the pitiless, blinding snow."[1]

And yet the glacialists would have us believe that Brazil and Africa, and the whole globe, were once wrapped in such a shroud of death!

Here, then, in conclusion, are the evidences that the deposits of the Drift are not due to continental ice-sheets:

I. The present ice-sheets of the remote north create no such deposits and make no such markings.

II. A vast continental elevation of land-surfaces at the north was necessary for the ice to slide down, and this did not exist.

III. The ice-sheet, if it made the Drift markings, must have scored the rocks going up-hill, while it did not score them going down-hill.

IV. If the cold formed the ice and the ice formed the Drift, why is there no Drift in the coldest regions of the earth, where there must have been ice?

V. Continental ice-belts, reaching to 40° of latitude, would have exterminated all tropical vegetation. It was not exterminated, therefore such ice-sheets could not have existed.

VI. The Drift is found in the equatorial regions of the world. If it was produced by an ice-sheet in those regions, all pre-glacial forms of life must have perished; but they did not perish; therefore the ice-sheet could not

[1. "Popular Science Monthly," April, 1874, p. 646.]

{p. 42}

have covered these regions, and could not have produced the drift-deposits there found.

In brief, the Drift is not found where ice must have been, and is found where ice could not have been; the conclusion, therefore, is irresistible that the Drift is not due to ice.

{p. 43}