WE turn now to the legends of mankind.

I shall try to divide them, so as to represent, in their order, the several stages of the great event. This, of course, will be difficult to do, for the same legend may detail several different parts of the same common story; and hence there may be more or less repetition; they will more or less overlap each other.

And, first, I shall present one or two legends that most clearly represent the first coming of the monster, the dragon, the serpent, the wolf, the dog, the Evil One, the Comet.

The second Hindoo "Avatar" gives the following description of the rapid advance of some dreadful object out of space, and its tremendous fall upon the earth:

"By the power of God there issued from the essence of Brahma a being shaped like a boar, white and exceeding small; this being, in the space of an hour, grew to the size of an elephant of the largest size, and remained in the air."

That is to say, it was an atmospheric, not a terrestrial creature.

"Brahma was astonished on beholding this figure, and discovered, by the force of internal penetration, that it could be nothing but the power of the Omnipotent which had assumed a body and become visible. He now felt that God is all in all, and all is from him, and all in him;

{p. 133}

and said to Mareechee and his sons (the attendant genii): 'A wonderful animal has emanated from my essence; at first of the smallest size, it has in one hour increased to this enormous bulk, and, without doubt, it is a portion of the almighty power.'"

Brahma, an earthly king, was at first frightened by the terrible spectacle in the air, and then claimed that he had produced it himself!

"They were engaged in this conversation when that vara, or 'boar-form,' suddenly uttered a sound like the loudest thunder, and the echo reverberated and shook all the quarters of the universe."

This is the same terrible noise which, as I have already shown, would necessarily result from the carbureted hydrogen of the comet exploding in our atmosphere. The legend continues:

"But still, under this dreadful awe of heaven, a certain wonderful divine confidence secretly animated the hearts of Brahma, Mareechee, and the other genii, who immediately began praises and thanksgiving. That vara (boar-form) figure, hearing the power of the Vedas and Mantras from their mouths, again made a loud noise, and became a dreadful spectacle. Shaking the full flowing mane which hung down his neck on both sides, and erecting the humid hairs of his body, he proudly displayed his two most exceedingly white tusks; then, rolling about his wine-colored (red) eyes, and erecting his tail, he descended from the region of the air, and plunged headforemost into the water. The whole body of water was convulsed by the motion, and began to rise in waves, while the guardian spirit of the sea, being terrified, began to tremble for his domain and cry for mercy.[1]

flow fully does this legend accord with the descriptions of comets given by astronomers, the "horrid hair," the mane, the animal-like head! Compare it with Mr.

[1. Maurice's "Ancient History of Hindustan," vol. i, p. 304.]

{p. 134}

Lockyer's account of Coggia's comet, as seen through Newell's large refracting telescope at Ferndene, Gateshead, and which he described as having a head like "a fan-shaped projection of light, with ear-like appendages, at each side, which sympathetically complemented each other at every change either of form or luminosity."

We turn to the legends of another race:

The Zendavesta of the ancient Persians[1] describes a period of "great innocence and happiness on earth."

This represents, doubtless, the delightful climate of the Tertiary period, already referred to, when endless summer extended to the poles.

"There was a 'man-bull,' who resided on an elevated region, which the deity had assigned him."

This was probably a line of kings or a nation, whose symbol was the bull, as we see in Bel or Baal, with the bull's horns, dwelling in some elevated mountainous region.

"At last an evil one, denominated Ahriman, corrupted the world. After having dared to visit heaven" (that is, he appeared first in the high heavens), "he descended upon the earth and assumed the form of a serpent."

That is to say, a serpent-like comet struck the earth.

"The man-bull was poisoned by his venom, and died in consequence of it. Meanwhile, Ahriman threw the whole universe into confusion (chaos), for that enemy of good mingled himself with everything, appeared everywhere, and sought to do mischief above and below."

We shall find all through these legends allusions to the poisonous and deadly gases brought to the earth by the comet: we have already seen that the gases which are proved to be associated with comets are fatal to life.

[1. Faber's "Horæ Mosaicæ," vol. i, p. 72.]

{p. 135}

And this, be it remembered, is not guess-work, but the revelation of the spectroscope.

The traditions of the ancient Britons[1] tell us of an ancient time, when

"The profligacy of mankind had provoked the great Supreme to send a pestilential wind upon the earth. A pure poison descended, every blast was death. At this time the patriarch, distinguished for his integrity, was shut up, together with his select company, in the inclosure with the strong door. (The cave?) Here the just ones were safe from injury. Presently a tempest of fire arose. It split the earth asunder to the great deep. The lake Llion burst its bounds, and the waves of the sea lifted themselves on high around the borders of Britain, the rain poured down from heaven, and the waters covered the earth."

Here we have the whole story told briefly, but with the regular sequence of events:

1. The poisonous gases.

2. The people seek shelter in the caves.

3. The earth takes fire.

4. The earth is cleft open; the fiords are made, and the trap-rocks burst forth.

5. The rain pours down.

6. There is a season of floods.

When we turn to the Greek legends, as recorded by one of their most ancient writers, Hesiod, we find the coming of the comet clearly depicted.

We shall see here, and in many other legends, reference to the fact that there was more than one monster in the sky. This is in accordance with what we now know to be true of comets. They often appear in pairs or even triplets. Within the past few years we have seen Biela's comet divide and form two separate comets, pursuing

[1. "Mythology of the British Druids," p. 226.]

{p. 136}

their course side by side. When the great comet of 1811 appeared, another of almost equal magnitude followed it. Seneca informs us that Ephoras, a Greek writer of the fourth century before Christ, had recorded the singular fact of a comet's separation into two parts.

"This statement was deemed incredible by the Roman philosopher. More recent observations of similar phenomena leave no room to question the historian's veracity."[1]

The Chinese annals record the appearance of three comets--one large and two smaller ones--at the same time, in the year 896 of our era.

"They traveled together for three days. The little ones disappeared first and then the large one."

And again:

"On June 27th, A. D. 416, two comets appeared in the constellation Hercules, and pursued nearly the same path."[2]

If mere proximity to the earth served to split Biela's comet into two fragments, why might not a comet, which came near enough to strike the earth, be broken into several separate forms?

So that there is nothing improbable in Hesiod's description of two or three aërial monsters appearing at or about the same time, or of one being the apparent offspring of the other, since a large comet may, like Biela's, have broken in two before the eyes of the people.

Hesiod tells us that the Earth united with Night to do a terrible deed, by which the Heavens were much wronged. The Earth prepared a large sickle of white iron, with jagged teeth, and gave it to her son Cronus, and stationed him in ambush, and when Heaven came, Cronus, his son, grasped at him, and with his "huge sickle, long and jagged-toothed," cruelly wounded him.

[1. Kirkwood, "Comets and Meteors," p. 60.

2. Ibid., p. 51.]

{p. 137}

Was this jagged, white, sickle-shaped object a comet?

"And Night bare also hateful Destiny, and black Fate, and Death, and Nemesis."

And Hesiod tells us that "she," probably Night--

"Brought forth another monster, irresistible, nowise like to mortal man or immortal gods, in a hollow cavern; the divine, stubborn-hearted Echidna (half-nymph, with dark eyes and fair cheeks; and half, on the other hand, a serpent, huge and terrible and vast), speckled, and flesh-devouring, 'neath caves of sacred Earth. . . . With her, they say that Typhaon (Typhon) associated in love, a terrible and lawless ravisher for the dark-eyed maid. . . . But she (Echidna) bare Chimæra, breathing resistless fire, fierce and huge, fleet-footed as well as strong; this monster had three heads: one, indeed, of a grim-visaged lion, one of a goat, and another of a serpent, a fierce dragon;

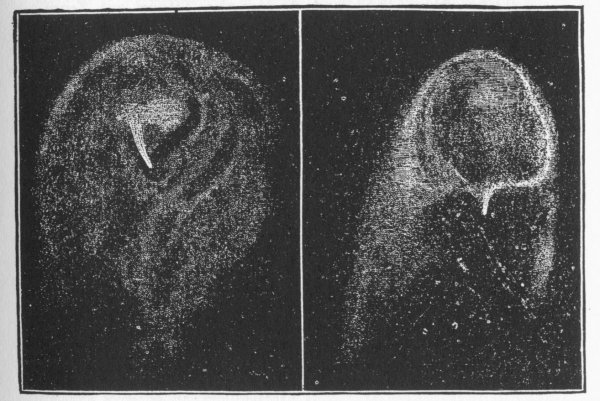

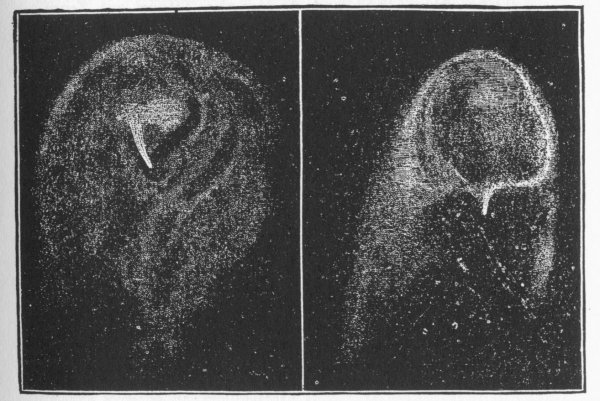

COMET OF 1862. Aspect of the head of the comet at nine in the evening, the 23d August, and the 24th August at the same hour.

{p. 138}

in front a lion, a dragon behind, and in the midst a goat, breathing forth the dread strength of burning fire. Her Pegasus slew and brave Bellerophon."

The astronomical works show what weird, and fantastic, and goblin-like shapes the comets assume under the telescope. Look at the representation on page 137, from Guillemin's work,[1] of the appearance of the comet of 1862, giving the changes which took place in twenty-four hours. If we will imagine one of these monsters close to the earth, we can readily suppose that the excited people, looking at "the dreadful spectacle," (as the Hindoo legend calls it,) saw it taking the shapes of serpents, dragons, birds, and wolves.

And Hesiod proceeds to tell us something more about this fiery, serpent-like monster:

"But when Jove had driven the Titans out from Heaven, huge Earth bare her youngest-born son, Typhœus (Typhaon, Typhœus, Typhon), by the embrace of Tartarus (Hell), through golden Aphrodite (Venus), whose hands, indeed, are apt for deeds on the score of strength, and untiring the feet of the strong god; and from his shoulders there were a hundred heads of a serpent, a fierce dragon playing with dusky tongues" (tongues of fire and smoke?), "and from the eyes in his wondrous heads are sparkled beneath the brows; whilst from all his heads fire was gleaming, as he looked keenly. In all his terrible heads, too, were voices sending forth every kind of voice ineffable. For one while, indeed, they would utter sounds, so as for the gods to understand, and at another time, again, the voice of a loud-bellowing bull, untamable in force and proud in utterance; at another time, again, that of a lion possessing a daring spirit; at another time, again, they would sound like to whelps, wondrous to hear; and at another, he would hiss, and the lofty mountains resounded.

[1. "The Heavens," p. 256.]

{p. 139}

"And, in sooth, then would there have been done a deed past remedy, and he, even he, would have reigned over mortals and immortals, unless, I wot, the sire of gods and men had quickly observed him. Harshly then he thundered, and heavily and terribly the earth re-echoed around; and the broad heaven above, and the sea and streams of ocean, and the abysses of earth. But beneath his immortal feet vast Olympus trembled, as the king uprose and earth groaned beneath. And the heat from both caught the dark-colored sea, both of the thunder and the lightning, and fire from the monster, the heat arising from the thunder-storms, winds, and burning lightning. And all earth, and heaven, and sea, were boiling; and huge billows roared around the shores about and around, beneath the violence of the gods; and unallayed quaking arose. Pluto trembled, monarch over the dead beneath; and the Titans under Tartarus, standing about Cronus, trembled also, on account of the unceasing tumult and dreadful contention. But Jove, when in truth he had raised high his wrath, and had taken his arms, his thunder and lightning, and smoking bolt, leaped up and smote him from Olympus, and scorched all around the wondrous heads of the terrible monster.

"But when at length he had quelled it, after having smitten it with blows, the monster fell down, lamed, and huge Earth groaned. But the flame from the lightning-blasted monster flashed forth in the mountain hollows, hidden and rugged, when he was stricken, and much was the vast earth burnt and melted by the boundless vapor, like as pewter, heated by the art of youths, and by the well-bored melting-pit, or iron, which is the hardest of metals, subdued in the dells of the mountain by blazing fire, melts in the sacred earth, beneath the hands of Vulcan. So, I wot, was earth melted in the glare of burning fire. Then, troubled in spirit, he hurled him into wide Tartarus."[1]

Here we have a very faithful and accurate narrative of the coming of the comet:

[1. "Theogony."]

{p. 140}

Born of Night a monster appears, a serpent, huge, terrible, speckled, flesh-devouring. With her is another comet, Typhaon; they beget the Chimæra, that breathes resistless fire, fierce, huge, swift. And Typhaon, associated with both these, is the most dreadful monster of all, born of Hell and sensual sin, a serpent, a fierce dragon, many-headed, with dusky tongues and fire gleaming; sending forth dreadful and appalling noises, while mountains and fields rock with earthquakes; chaos has come; the earth, the sea boils; there is unceasing tumult and contention, and in the midst the monster, wounded and broken up, falls upon the earth; the earth groans under his weight, and there he blazes and burns for a time in the mountain fastnesses and desert places, melting the earth with boundless vapor and glaring fire.

We will find legend after legend about this Typhon he runs through the mythologies of different nations. And as to his size and his terrible power, they all agree. He was no earth-creature. He moved in the air; he reached the skies:

"According to Pindar the head of Typhon reached to the stars, his eyes darted fire, his hands extended from the East to the West, terrible serpents were twined about the middle of his body, and one hundred snakes took the place of fingers on his hands. Between him and the gods there was a dreadful war. Jupiter finally killed him with a flash of lightning, and buried him under Mount Etna."

And there, smoking and burning, his great throes and writhings, we are told, still shake the earth, and threaten mankind:

And with pale lips men say,

'To-morrow, perchance to-day,

Encelidas may arise! "'

{p. 141}