HUMBOLDT Says:

"It is probable that the vapor of the tails of comets mingled with our atmosphere in the years 1819 and 1823."[1]

There is reason to believe that the present generation has passed through the gaseous prolongation of a comet's tail, and that hundreds of human beings lost their lives, somewhat as they perished in the Age of Fire and Gravel, burned up and poisoned by its exhalations.

And, although this catastrophe was upon an infinitely smaller scale than that of the old time, still it may throw some light upon the great cataclysm. At least it is a curious story, with some marvelous features:

On the 27th day of February, 1826, (to begin as M. Dumas would commence one of his novels,) M. Biela, an Austrian officer, residing at Josephstadt, in Bohemia, discovered a comet in the constellation Aries, which, at that time, was seen as a small round speck of filmy cloud. Its course was watched during the following month by M. Gambart at Marseilles and by M. Clausen at Altona, and those observers assigned to it an elliptical orbit, with a period of six years and three quarters for its revolution.

M. Damoiseau subsequently calculated its path, and announced that on its next return the comet would cross

[1. "Cosmos," Vol. i, p. 100.]

{p. 409}

the orbit of the earth, within twenty thousand miles of its track, and but about one month before the earth would have arrived at the same spot!

This was shooting close to the bull's-eye!

He estimated that it would lose nearly ten days on its return trip, through the retarding influence of Jupiter and Saturn; but, if it lost forty days instead of ten, what then?

But the comet came up to time in 1832, and the earth missed it by one month.

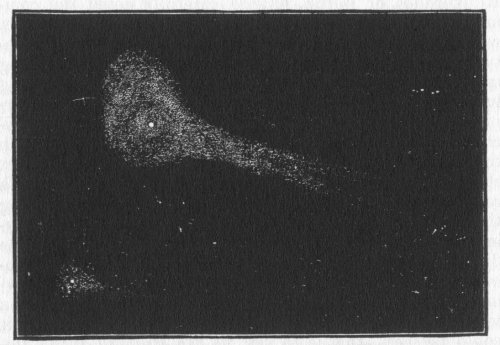

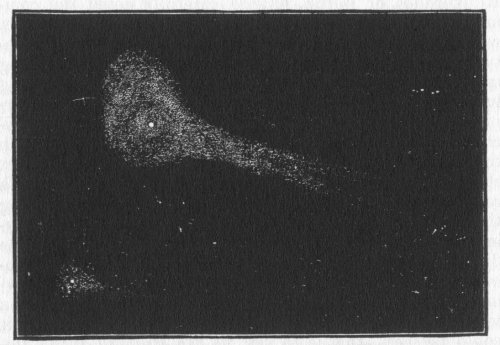

And it returned in like fashion in 1839 and 1846. But here a surprising thing occurred. Its proximity to the earth had split it in two; each half had a head and tail of its own; each had set up a separate government for itself; and they were whirling through space, side by side, like a couple of race-horses, about sixteen thousand miles apart, or about twice as wide apart as the diameter of the earth. Here is a picture of them, drawn from life.

BIELA'S COMET, SPLIT IN TWO, (From Guillemin's "The Heavens," page 247.)

{p. 410} Did the Fenris-Wolf, the Midgard-Serpent, and the Dog-Garm look like this?

In 1852, 1859, and 1866, the comet SHOULD have returned, but it did not. It was lost. It was dissipated. Its material was banging around the earth in fragments somewhere. I quote from a writer in a recent issue of the "Edinburgh Review":

The puzzled astronomers were left in a state of tantalizing uncertainty as to what had become of it. At the beginning of the year 1866 this feeling of bewilderment gained expression in the Annual Report of the Council of the Royal Astronomical Society. The matter continued, nevertheless, in the same state of provoking uncertainty for another six years. The third period of the perihelion passage had then passed, and nothing had been seen of the missing luminary. But on the night of November 27, 1872, night-watchers were startled by a sudden and a very magnificent display of falling stars or meteors, of which there had been no previous forecast, and Professor Klinkerflues, of Berlin, having carefully noted the common radiant point in space from which this star-shower was discharged into the earth's atmosphere, with the intuition of ready genius jumped at once to the startling inference that here at last were traces of the missing luminary. There were eighty of the meteors that furnished a good position for the radiant point of the discharge, and that position, strange to say, was very much the same as the position in space which Biela's comet should have occupied just about that time on its fourth return toward perihelion. Klinkerflues, therefore, taking this spot as one point in the path of the comet, and carrying the path on as a track into forward space, fixed the direction there through which it should pass as a 'vanishing-point' at the other side of the starry sphere, and having satisfied himself of that further position he sent off a telegram to the other side of the world, where alone it could be seen--that is to say, to Mr. Pogson, of the Madras Observatory--which may be best told in his own nervous and simple words.

{p. 411}

Herr Klinkerflues's telegram to Mr. Pogson, of Madras, was to the following effect:

"'November 30th--Biela touched the earth on the 27th of November. Search for him near Theta Centauri.'

"The telegram reached Madras, through Russia, in one hour and thirty-five minutes, and the sequel of this curious passage of astronomical romance may be appropriately told in the words in which Mr. Pogson replied to Herr Klinkerflues's pithy message. The answer was dated Madras, the 6th of December, and was in the following words:

"'On the 30th of November, at sixteen hours, the time of the comet rising here, I was at my post, but hopelessly; clouds and rain gave me no chance. The next morning I had the same bad luck. But on the third trial, with a line of blue break, about 17¼ hours mean time, I found Biela immediately! Only four comparisons in successive minutes could be obtained, in strong morning twilight, with an anonymous star; but direct motion of 2.5 seconds decided that I had got the comet all right. I noted it--circular, bright, with, a decided nucleus, but NO TAIL, and about forty-five seconds in diameter. Next morning I got seven good comparisons with an anonymous star, showing a motion of 17.9 seconds in twenty-eight minutes, and I also got two comparisons with a Madras star in our current catalogue, and with 7,734 Taylor. I was too anxious to secure one good place for the one in hand to look for the other comet, and the fourth morning was cloudy and rainy.'

"Herr Klinkerflues's commentary upon this communication was that he forthwith proceeded to satisfy himself that no provoking accident had led to the discovery of a comet altogether unconnected with Biela's, although in this particular place, and that he was ultimately quite confident of the identity of the comet observed by Mr. Pogson with one of the two heads of Biela. It was subsequently settled that Mr. Pogson had, most probably, seen both heads of the comet, one on the first occasion of his successful search, and the second on the following day; and the meteor-shower experienced in Europe on November 27th was unquestionably due to the passage

{p. 412}

near the earth of a meteoric trail traveling in the track of the comet. When the question of a possible collision was mooted in 1832, Sir John Herschel remarked that such an occurrence might not be unattended with danger, and that on account of the intersection of the orbits of the earth and the comet a rencontre would in all likelihood take place within the lapse of some millions of years. As a matter of fact the collision did take place on November 27, 1872, and the result, so far as the earth was concerned, was a magnificent display of aërial fireworks! But a more telling piece of ready-witted sagacity than this prompt employment of the telegraph for the apprehension of the nimble delinquent can scarcely be conceived. The sudden brush of the comet's tail, the instantaneous telegram to the opposite side of the world, and the glimpse thence of the vagrant luminary as it was just whisking itself off into space toward the star Theta Centauri, together constitute a passage that stands quite without a parallel in the experience of science."

But did the earth escape with a mere shower of fireworks?

I have argued that the material of a comet consists of a solid nucleus, giving out fire and gas, enveloped in a great gaseous mass, and a tail made up of stones, possibly gradually diminishing in size as they recede from the nucleus, until the after-part of it is composed of fine dust ground from the pebbles and bowlders; while beyond this there may be a still further prolongation into gaseous matter.

Now, we have seen that Biela's comets lost their tails. What became of them? There is no evidence to show whether they lost them in 1852, 1859, 1866, or 1872. The probabilities are that the demoralization took place before 1852, as otherwise the comets would have been seen, tails and all, in that and subsequent years. It is true that the earth came near enough in 1872 to attract some of the wandering gravel-stones toward itself, and that they fell,

{p. 413}

blazing and consuming themselves with the friction of our atmosphere, and reached the surface of our planet, if at all, as cosmic dust. But where were the rest of the assets of these bankrupt comets? They were probably scattered around in space, disjecta membra, floating hither and thither, in one place a stream of stones, in another a volume of gas; while the two heads had fled away, like the fugitive presidents of a couple of broken banks, to the Canadian refuge of "Theta Centauri"--shorn of their splendors and reduced to first principles.

Did anything out of the usual order occur on the face of the earth about this time?

Yes. In the year 1871, on Sunday, the 8th of October, at half past nine o'clock in the evening, events occurred which attracted the attention of the whole world, which caused the death of hundreds of human beings, and the destruction of millions of property, and which involved three different States of the Union in the wildest alarm and terror.

The summer of 1871 had been excessively dry; the moisture seemed to be evaporated out of the air; and on the Sunday above named the atmospheric conditions all through the Northwest were of the most peculiar character. The writer was living at the time in Minnesota, hundreds of miles from the scene of the disasters, and he can never forget the condition of things. There was a parched, combustible, inflammable, furnace-like feeling in the air, that was really alarming. It felt as if there were needed but a match, a spark, to cause a world-wide explosion. It was weird and unnatural. I have never seen nor felt anything like it before or since. Those who experienced it will bear me out in these statements.

At that hour, half past nine o'clock in the evening, at apparently the same moment, at points hundreds of miles

{p. 414}

apart, in three different States, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois, fires of the most peculiar and devastating kind broke out, so far as we know, by spontaneous combustion.

In Wisconsin, on its eastern borders, in a heavily timbered country, near Lake Michigan, a region embracing four hundred square miles, extending north from Brown County, and containing Peshtigo, Manistee, Holland, and numerous villages on the shores of Green Bay, was swept bare by an absolute whirlwind of flame. There were seven hundred and fifty people killed outright, besides great numbers of the wounded, maimed, and burned, who died afterward. More than three million dollars' worth of property was destroyed.[1]

It was no ordinary fire. I quote:

"At sundown there was a lull in the wind and comparative stillness. For two hours there were no signs of danger; but at a few minutes after nine o'clock, and by a singular coincidence, precisely the time at which the Chicago fire commenced, the people of the village heard a terrible roar. It was that of a tornado, crushing through the forests. Instantly the heavens were illuminated with a terrible glare. The sky, which had been so dark a moment before, burst into clouds of flame. A spectator of the terrible scene says the fire did not come upon them gradually from burning trees and other objects to the windward, but the first notice they had of it was a whirlwind of flame in great clouds from above the tops of the trees, which fell upon and entirely enveloped everything. The poor people inhaled it, or the intensely hot air, and fell down dead. This is verified by the appearance of many of the corpses. They were found dead in the roads and open spaces, where there were no visible marks of fire near by, with not a trace of burning upon their bodies or clothing. At the Sugar Bush, which is an extended clearing, in some places four miles in width,

[1. See "History of the Great Conflagration," Sheahan & Upton, Chicago, 1871, pp. 393, 394, etc.]

{p. 415}

corpses were found in the open road, between fences only slightly burned. No mark of fire was upon them; they lay there as if asleep. This phenomenon seems to explain the fact that so many were killed in compact masses. They seemed to have huddled together, in what were evidently regarded at the moment as the safest places, far away from buildings, trees, or other inflammable material, and there to have died together."[1]

Another spectator says:

"Much has been said of the intense heat of the fires which destroyed Peshtigo, Menekaune, Williamsonville, etc., but all that has been said can give the stranger but a faint conception of the reality. The heat has been compared to that engendered by a flame concentrated on an object by a blow-pipe; but even that would not account for some of the phenomena. For instance, we have in our possession a copper cent taken from the pocket of a dead man in the Peshtigo Sugar Bush, which will illustrate our point. This cent has been partially fused, but still retains its round form, and the inscription upon it is legible. Others, in the same pocket, were partially melted, and yet the clothing and the body of the man were not even singed. We do not know in what way to account for this, unless, as is asserted by some, the tornado and fire were accompanied by electrical phenomena."[2]

"It is the universal testimony that the prevailing idea among the people was, that the last day had come. Accustomed as they were to fire, nothing like this had ever been known. They could give no other interpretation to this ominous roar, this bursting of the sky with fame, and this dropping down of fire out of the very heavens, consuming instantly everything it touched.

"No two give a like description of the great tornado as it smote and devoured the village. It seemed as if 'the fiery fiends of hell had been loosened,' says one. 'It came in great sheeted flames from heaven,' says another. 'There was a pitiless rain of fire and SAND.' 'The

[1. See "History of the Great Conflagration," Sheahan & Upton, Chicago, 1871, p. 372.

2. Ibid., p. 373.]

{p. 416}

atmosphere was all afire.' Some speak of 'great balls of fire unrolling and shooting forth, in streams.' The fire leaped over roofs and trees, and ignited whole streets at once. No one could stand before the blast. It was a race with death, above, behind, and before them."[1]

A civil engineer, doing business in Peshtigo, says

"The heat increased so rapidly, as things got well afire, that, when about four hundred feet from the bridge and the nearest building, I was obliged to lie down behind a log that was aground in about two feet of water, and by going under water now and then, and holding my head close to the water behind the log, I managed to breathe. There were a dozen others behind the same log. If I had succeeded in crossing the river and gone among the buildings on the other side, probably I should have been lost, as many were."

We have seen Ovid describing the people of "the earth" crouching in the same way in the water to save themselves from the flames of the Age of Fire.

In Michigan, one Allison Weaver, near Port Huron, determined to remain, to protect, if possible, some mill-property of which he had charge. He knew the fire was coming, and dug himself a shallow well or pit, made a thick plank cover to place over it, and thus prepared to bide the conflagration.

I quote:

"He filled it nearly full of water, and took care to saturate the ground around it for a distance of several rods. Going to the mill, he dragged out a four-inch plank, sawed it in two, and saw that the parts tightly covered the mouth of the little well. 'I kalkerated it would be tech and go,' said he, 'but it was the best I could do.' At midnight he had everything arranged, and the roaring then was

[1. See "History of the Great Conflagration," Sheahan & Upton, Chicago, 1871, p. 374.]

{p. 417}

awful to hear. The clearing was ten to twelve acres in extent, and Weaver says that, for two hours before the fire reached him, there was a constant flight across the ground of small animals. As he rested a moment from giving the house another wetting down, a horse dashed into the opening at full speed and made for the house. Weaver could see him tremble and shake with excitement and terror, and felt a pity for him. After a moment the animal gave utterance to a snort of dismay, ran two or three times around the house, and then shot on into the woods like a rocket."

We have, in the foregoing pages, in the legends of different nations, descriptions of the terrified animals flying with the men into the caves of the earth to escape the great conflagration.

'I Not long after this the fire came. Weaver stood by his well, ready for the emergency, yet curious to see the breaking-in of the flames. The roaring increased in volume, the air became oppressive, a cloud of dust and cinders came showering down, and he could see the flame through the trees. It did not run along the ground, or leap from tree to tree, but it came on like a tornado, a sheet of flame reaching from the earth to the tops of the trees. As it struck the clearing he jumped into his well, and closed over the planks. He could no longer see, but he could hear. He says that the flames made no halt whatever, or ceased their roaring for an instant, but he hardly got the opening closed before the house and mill were burning tinder, and both were down in five minutes. The smoke came down upon him powerfully, and his den was so hot he could hardly breathe.

"He knew that the planks above him were on fire, but, remembering their thickness, he waited till the roaring of the flames had died away, and then with his head and hands turned them over and put out the fire by dashing up water with his hands. Although it was a cold night, and the water had at first chilled him, the heat gradually warmed him up until he felt quite comfortable. He remained in his den until daylight, frequently turning

{p. 418}

over the planks and putting out the fire, and then the worst had passed. The earth around was on fire in spots, house and mill were gone, leaves, brush, and logs were swept clean away as if shaved off and swept with a broom, and nothing but soot and ashes were to be seen."[1]

In Wisconsin, at Williamson's Mills, there was a large but shallow well on the premises belonging to a Mr. Boorman. The people, when cut off by the flames and wild with terror, and thinking they would find safety in the water, leaped into this well. "The relentless fury of the flames drove them pell-mell into the pit, to struggle with each other and die--some by drowning, and others by fire and suffocation. None escaped. Thirty-two bodies were found there. They were in every imaginable position; but the contortions of their limbs and the agonizing expressions of their faces told the awful tale."[2]

The recital of these details, horrible though they may be, becomes excusable when we remember that the ancestors of our race must have endured similar horrors in that awful calamity which I have discussed in this volume.

James B. Clark, of Detroit, who was at Uniontown, Wisconsin, writes:

"The fire suddenly made a rush, like the flash of a train of gunpowder, and swept in the shape of a crescent around the settlement. It is almost impossible to conceive the frightful rapidity of the advance of the flames. The rushing fire seemed to eat up and annihilate the trees."

They saw a black mass coming toward them from the wall of flame:

"It was a stampede of cattle and horses thundering toward us, bellowing moaning, and neighing as they galloped

[1. See "History of the Great Conflagration," Sheahan & Upton, Chicago, 1871, p. 390.

2. Ibid., p. 386.]

{p. 419}

on; rushing with fearful speed, their eyeballs dilated and glaring with terror, and every motion betokening delirium of fright. Some had been badly burned, and must have plunged through a long space of flame in the desperate effort to escape. Following considerably behind came a solitary horse, panting and snorting and nearly exhausted. He was saddled and bridled, and, as we first thought, had a bag lashed to his back. As he came up we were startled at the sight of a young lad lying fallen over the animal's neck, the bridle wound around his hands, and the mane being clinched by the fingers. Little effort was needed to stop the jaded horse, and at once release the helpless boy. He was taken into the house, and all that we could do was done; but he had inhaled the smoke, and was seemingly dying. Some time elapsed and he revived enough to speak. He told his name--Patrick Byrnes--and said: 'Father and mother and the children got into the wagon. I don't know what became of them. Everything is burned up. I am dying. Oh! is hell any worse than this?'"[1]

How vividly does all this recall the book of Job and the legends of Central America, which refer to the multitudes of the burned, maimed, and wounded lying in the caverns, moaning and crying like poor Patrick Byrnes, suffering no less in mind than in body!

When we leave Wisconsin and pass about two hundred and fifty miles eastward, over Lake Michigan and across the whole width of the State of Michigan, we find much the same condition of things, but not so terrible in the loss of human life. Fully fifteen thousand people were rendered homeless by the fires; and their food, clothing, crops, horses, and cattle were destroyed. Of these five to six thousand were burned out the same night that the fires broke out in Chicago and Wisconsin. The

[1. See "History of the Great Conflagration," Sheahan & Upton, Chicago, 1871, p. 383.]

{p. 420}

total destruction of property exceeded one million dollars; not only villages and cities, but whole townships, were swept bare.

But it is to Chicago we must turn for the most extraordinary results of this atmospheric disturbance. It is needless to tell the story in detail. The world knows it by heart:

Blackened and bleeding, helpless, panting, prone,

On the charred fragments of her shattered throne,

Lies she who stood but yesterday alone."

I have only space to refer to one or two points.

The fire was spontaneous. The story of Mrs. O'Leary's cow having started the conflagration by kicking over a lantern was proved to be false. It was the access of gas from the tail of Biela's comet that burned up Chicago!

The fire-marshal testified:

"I felt it in my bones that we were going to have a burn."

He says, speaking of O'Leary's barn:

"We got the fire under control, and it would not have gone a foot farther; but the next thing I knew they came and told me that St. Paul's church, about two squares north, was on fire."[1]

They checked the church-fire, but--

"The next thing I knew the fire was in Bateham's planing-mill."

A writer in the New York "Evening Post" says he saw in Chicago "buildings far beyond the line of fire, and in no contact with it, burst into flames from the interior."

[1. See "History of the Great Conflagration," Sheahan & Upton, Chicago, 1871, p. 163.]

{p. 421}

It must not be forgotten that the fall of 1871 was marked by extraordinary conflagrations in regions widely separated. On the 8th. of October, the same day the Wisconsin, Michigan, and Chicago fires broke out, the States of Iowa, Minnesota, Indiana, and Illinois were severely devastated by prairie-fires; while terrible fires raged on the Alleghanies, the Sierras of the Pacific coast, and the Rocky Mountains, and in the region of the Red River of the North.

"The Annual Record of Science and Industry" for 1876, page 84, says:

"For weeks before and after the great fire in Chicago in 1872, great areas of forest and prairie-land, both in the United States and the British Provinces, were on fire."

The flames that consumed a great part of Chicago were of an unusual character and produced extraordinary effects. They absolutely melted the hardest building-stone, which had previously been considered fire-proof. Iron, glass, granite, were fused and run together into grotesque conglomerates, as if they had been put through a blast-furnace. No kind of material could stand its breath for a moment.

I quote again from Sheahan & Upton's Work:

"The huge stone and brick structures melted before the fierceness of the flames as a snow-flake melts and disappears in water, and almost as quickly. Six-story buildings would take fire and disappear for ever from sight in five minutes by the watch. . . . The fire also doubled on its track at the great Union Depot and burned half a mile southward in the very teeth of the gale--a gale which blew a perfect tornado, and in which no vessel could have lived on the lake. . . . Strange, fantastic fires of blue, red, and green played along the cornices of buildings."[1]

[1. "History of the Chicago Fire," pp. 85, 86.]

{p. 422}

Hon. William B. Ogden wrote at the time:

"The fire was accompanied by the fiercest tornado of wind ever known to blow here."[1]

"The most striking peculiarity of the fire was its intense heat. Nothing exposed to it escaped. Amid the hundreds of acres left bare there is not to be found a piece of wood of any description, and, unlike most fires, it left nothing half burned. . . . The fire swept the streets of all the ordinary dust and rubbish, consuming it instantly."[2]

The Athens marble burned like coal!

"The intensity of the heat may be judged, and the thorough combustion of everything wooden may be understood, when we state that in the yard of one of the large agricultural-implement factories was stacked some hundreds of tons of pig-iron. This iron was two hundred feet from any building. To the south of it was the river, one hundred and fifty feet wide. No large building but the factory was in the immediate vicinity of the fire. Yet, so great was the heat, that this pile of iron melted and run, and is now in one large and nearly solid mass."[3]

The amount of property destroyed was estimated by Mayor Medill at one hundred and fifty million dollars; and the number of people rendered houseless, at one hundred and twenty-five thousand. Several hundred lives were lost.

All this brings before our eyes vividly the condition of things when the comet struck the earth; when conflagrations spread over wide areas; when human beings were consumed by the million; when their works were obliterated, and the remnants of the multitude fled before the rushing flames, filled with unutterable consternation;

[1. "History of the Chicago Fire," p. 87.

2. Ibid., p. 119.

3. Ibid., p. 121.]

{p. 423}

and as they jumped pell-mell into wells, so we have seen them in Job clambering down ropes into the narrow-mouthed, bottomless pit.

Who shall say how often the characteristics of our atmosphere have been affected by accessions from extraterrestrial sources, resulting in conflagrations or pestilences, in failures of crops, and in famines? Who shall say how far great revolutions and wars and other perturbations of humanity have been due to similar modifications? There is a world of philosophy in that curious story, "Dr. Ox's Hobby," wherein we are told how he changed the mental traits of a village of Hollanders by increasing the amount of oxygen in the air they breathed.

{p. 424}