|

by Stephen Smith from Thunderbolts Website

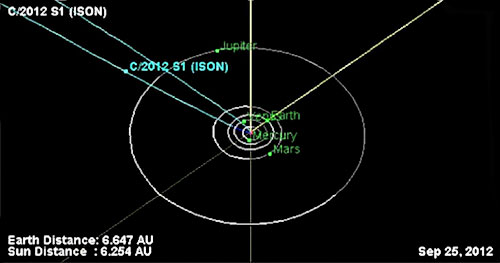

Orbital diagram of comet 2012 S1. Credit: JPL Small Body Database.

Are comets “dirty snowballs”?

Comet 2012 S1, an object approximately three kilometers in diameter, is presently inside the orbit of Jupiter.

It is “remarkably bright” according to astronomers, although it is still millions of kilometers from the Sun. Since it is so bright already, it has been speculated that it might become one of the most luminous comets ever witnessed.

Comets spend most of their time far from the Sun where the Solar System’s charge density is low. Since they move slowly, their electric charges reach equilibrium with the weak, radial solar field. As they get closer to the Sun, however, their nuclei speed into regions of increasing charge density and varying electrical flux.

Their polarity and charge characteristics respond to the increasing solar forces, so a coma (charge sheath) forms around them.

Discharge jets flare up and move across the surface in the same way as the plumes of Jupiter’s moon, Io. If the charge imbalance becomes too great, the nucleus might explode like an overcharged capacitor, breaking into fragments or vanishing forever.

Another reason that comets might exhibit increased activity is that they encounter some other strong electric field, such as in the vicinity of a gas giant planet (like Jupiter). In October of 2007, the unexpected brightening of comet Holmes 17P occurred for what astronomers at the time deemed “no apparent reason”.

Overall, it gradually brightened from 17th magnitude to about 2.5 magnitude, bringing it up naked-eye luminosity.

In a previous article about the fissioning of comet West in 1976, it was noted that comets tend to split or to undergo anomalous displays when they are approaching their farthest distance from the Sun. Because conventional theories of the solar system based exclusively on gravity expect disruptions only at close approaches to the Sun, the activity of comet West was a surprise.

Comet Linear was a profound surprise to astronomers in July of 2000 when it actually blew apart.

The strangest thing about its fragmentation was that it occurred at a distance of over 100 million kilometers from the Sun and not when it passed by during perihelion. Another counterintuitive observation is that so-called “sun-grazer” comets do not break apart despite approaching to within 50,000 kilometers of the Sun’s surface in some cases.

Four years after its encounter with the Sun, the large comet Hale-Bopp did not obey the standard theory of cometary activity. In the deep places of the Solar System, past Jupiter’s orbit, the comet displayed an ion tail, several jets of bright material spewing into space and a glowing coma.

The “dirty snowball” theory cannot account for such activity at distances where solar energy emissions are so weak that ice will not melt.

As has been written in the past, if solar heating were responsible for cometary discharges at such distances, then all the frozen moons of Jupiter would be as dry as deserts and would look more like our own moon than the icy bodies that they are.

If the Sun’s warmth was not the cause of Hale-Bopp’s display, then what is it that provides the energy for supersonic blasts of dust and ice when it is so far away? To reiterate, it is the presence of an energetic electric field that charges the cometary capacitor.

It seems apparent, based on previous observations, that comets are not the icy mud balls that astronomers think they are. Numerous examples of why that theory ought to be consigned to the “circular file” have been detailed in these pages.

2012 S1 could indeed become a spectacular apparition in Earth’s sky, although this author recalls comet Kohoutek, the so-called “comet of the century,” which subsequently became synonymous with spectacular duds.

However, 2012 S1′s chance depends on factors that have nothing to do with how much dust is on its surface, how much ice is contained in its nucleus, or how close it approaches the Sun. What will determine its fate is the electrical potential that will develop between the comet and the Sun.

How much charge it will accumulate, and how rapidly that charge disperses are going to be the deciding factors.

Electric Universe advocate Wal Thornhill wrote:

|