|

by Steve Connor

12 November 2012

from

TheIndependent Website

Spanish version

Is the human species doomed to intellectual decline? Will our

intelligence ebb away in centuries to come leaving our descendants

incapable of using the technology their ancestors invented?

In short: will Homo be left

without his sapiens?

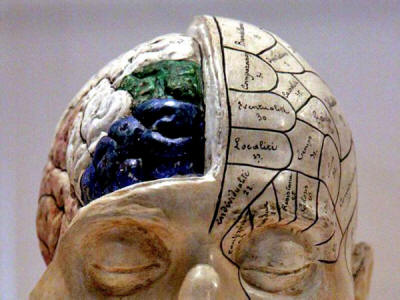

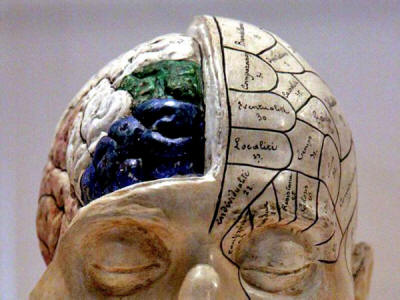

This is the controversial hypothesis of a leading geneticist who

believes that the immense capacity of the human brain to learn new

tricks is under attack from an array of genetic mutations that have

accumulated since people started living in cities a few thousand

years ago.

Professor

Gerald Crabtree, who heads a

genetics laboratory at Stanford University in California, has put

forward the iconoclastic idea (see

Our Fragile Intellect)

that rather than getting cleverer, human intelligence peaked several

thousand years ago and from then on there has been a slow decline in

our intellectual and emotional abilities.

Although we are now surrounded by the technological and medical

benefits of a scientific revolution, these have masked an underlying

decline in brain power which is set to continue into the future

leading to the ultimate dumbing-down of the human species, Professor

Crabtree said.

His argument is based on the fact that for more than 99 per cent of

human evolutionary history, we have lived as hunter-gatherer

communities surviving on our wits, leading to big-brained humans.

Since the invention of agriculture and

cities, however, natural selection on our intellect has effective

stopped and mutations have accumulated in the critical

“intelligence” genes.

“I would wager that if an average

citizen from Athens of 1000BC were to appear suddenly among us,

he or she would be among the brightest and most intellectually

alive of our colleagues and companions, with a good memory, a

broad range of ideas and a clear-sighted view of important

issues,” Professor Crabtree says in a provocative paper

published in the journal Trends in Genetics.

“Furthermore, I would guess that he

or she would be among the most emotionally stable of our friends

and colleagues. I would also make this wager for the ancient

inhabitants of Africa, Asia, India or the Americas, of perhaps

2,000 to 6,000 years ago,” Professor Crabtree says.

“The basis for my wager comes from new developments in genetics,

anthropology, and neurobiology that make a clear prediction that

our intellectual and emotional abilities are genetically

surprisingly fragile,” he says.

(Our

Fragile Intellect)

A comparison of the genomes of parents

and children has revealed that on average there are between 25 and

65 new mutations occurring in the DNA of each generation.

Professor Crabtree says that this

analysis predicts about 5,000 new mutations in the past 120

generations, which covers a span of about 3,000 years.

Some of these mutations, he suggests, will occur within the 2,000 to

5,000 genes that are involved in human intellectual ability, for

instance by building and mapping the billions of nerve cells of the

brain or producing the dozens of chemical neurotransmitters that

control the junctions between these brain cells.

Life as a hunter-gatherer was probably more intellectually demanding

than widely supposed, he says.

“A hunter-gatherer who did not

correctly conceive a solution to providing food or shelter

probably died, along with his or her progeny, whereas a modern

Wall Street executive that made a similar conceptual mistake

would receive a substantial bonus and be a more attractive

mate,” Professor Crabtree says.

However, other scientists remain

skeptical.

“At first sight this is a classic

case of Arts Faculty science. Never mind the hypothesis, give me

the data, and there aren’t any,” said Professor Steve Jones, a

geneticist at University College London.

“I could just as well argue that mutations have reduced our

aggression, our depression and our penis length but no journal

would publish that. Why do they publish this?” Professor Jones

said.

“I am an advocate of

Gradgrind 'science'

- facts, facts and more facts; but we need ideas too, and this

is an ideas paper although I have no idea how the idea could be

tested,” he said.

THE DESCENT OF MAN

-

Hunter-gatherer man - The human

brain and its immense capacity for knowledge evolved during

this long period of prehistory when we battled against the

elements

-

Athenian man - The invention of

agriculture less than 10,000 years ago and the subsequent

rise of cities such as Athens relaxed the intensive natural

selection of our “intelligence genes”.

-

Couch-potato man - As genetic

mutations increase over future generations, are we doomed to

watching soap-opera repeats without knowing how to use the

TV remote control?

-

iPad man - The fruits of science

and technology enabled humans to rise above the constraints

of nature and cushioned our fragile intellect from genetic

mutations.

Research Suggests That Humans Are Slowly But

Surely...

Losing Intellectual and Emotional

Abilities

by Lisa Lyons

12 November 2012

from

EurekAlert Website

Human intelligence and behavior require optimal functioning of a

large number of genes, which requires enormous evolutionary

pressures to maintain.

A provocative hypothesis published in a

recent set of Science and Society pieces published in the Cell Press

journal Trends in Genetics (see

Our Fragile Intellect)

suggests that we are losing our intellectual and emotional

capabilities because the intricate web of genes endowing us with our

brain power is particularly susceptible to mutations and that these

mutations are not being selected against in our modern society.

"The development of our intellectual

abilities and the optimization of thousands of intelligence

genes probably occurred in relatively non-verbal, dispersed

groups of peoples before our ancestors emerged from Africa,"

says the papers' author, Dr. Gerald Crabtree, of Stanford

University.

In this environment, intelligence was

critical for survival, and there was likely to be immense selective

pressure acting on the genes required for intellectual development,

leading to a peak in human intelligence.

From that point, it's likely that we began to slowly lose ground.

With the development of agriculture,

came urbanization, which may have weakened the power of selection to

weed out mutations leading to intellectual disabilities.

Based on calculations of the frequency

with which deleterious mutations appear in the human genome and the

assumption that 2000 to 5000 genes are required for intellectual

ability, Dr. Crabtree estimates that within 3000 years (about

120 generations) we have all sustained two or more mutations harmful

to our intellectual or emotional stability.

Moreover, recent findings from

neuroscience suggest that genes involved in brain function are

uniquely susceptible to mutations.

Dr. Crabtree argues that the combination

of less selective pressure and the large number of easily affected

genes is eroding our intellectual and emotional capabilities.

But not to worry...

The loss is quite slow, and judging by

society's rapid pace of discovery and advancement, future

technologies are bound to reveal solutions to the problem.

"I think we will know each of the

millions of human mutations that can compromise our intellectual

function and how each of these mutations interact with each

other and other processes as well as environmental influences,"

says Dr. Crabtree.

"At that time, we may be able to

magically correct any mutation that has occurred in all cells of

any organism at any developmental stage. Thus, the brutish

process of natural selection will be unnecessary."

|