|

|

|

from ExtremeTech Website

Scientists working at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab) near Chicago have successfully communicated a short digital message using a stream of neutrinos.

While this sounds cool, the truly exceptional bit is that the message was transmitted through 790 feet (240m) of solid stone.

Neutrinos are subatomic particles (like electrons or quarks, or the theorized Higgs Boson) that have almost zero mass, a neutral charge (thus their name), and travel at close to the speed of light.

Unlike almost every other particle in the universe, neutrinos are unaffected by electromagnetism (because of their neutral charge), and only subject to gravity and weak nuclear force. This means that neutrinos can easily pass through solid objects as large as planets.

Every second, 65 billion neutrinos from the Sun pass through each square centimeter of the Earth at almost the speed of light.

To recreate this effect, the Fermilab scientists used a particle accelerator (NuMI) to shoot a stream of neutrinos through 240 meters of stone at the MINERvA neutrino detector.

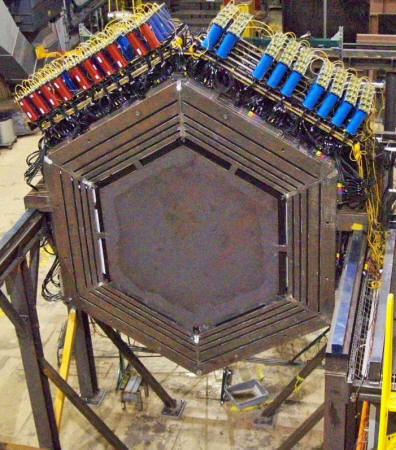

If MINERvA detected neutrinos, it registered as a binary 1; no neutrinos, binary 0. Using this technique (pictured above), the scientists, with a burst of originality to rival Alexander Graham Bell himself, transmitted the word "neutrino."

Now, there's nothing to stop Fermilab from pointing their particle gun at the ground and shooting neutrinos all the way through the Earth to Chicago's antipode near Australia.

This would instantly become the fastest communication network on the planet:

Satellite networks, which are still regularly used for telecoms, have to bounce through 50,000 miles or more. In theory, anyway.

The same properties that allow neutrinos to pass through whole planets also make them very hard to detect.

MINERvA is a large, multi-ton slab of metal (pictured above), and yet it can only detect one neutrino in 10 billion.

Producing all of those neutrinos requires a huge amount of energy and a particle accelerator, which is usually a few miles in length (CERN's Large Hadron Collider is 17 miles in circumference and 100 meters underground).

Suffice it to say, then, that mere mortals won't be building neutrino networks any time soon, but there are definitely military and government applications.

Similar to quantum networks, it would be very hard to wiretap a neutrino burst. Likewise, neutrinos could also be used to communicate with submarines, which have very limited communication channels (radio waves really don't like water).

Then there's the interstellar internet - or Galnet, as I like to call it - where you really don't want a wireless signal to hit an obstacle (a star, planet, spaceship…) half way there.

More information at "Demonstration of Communication Using Neutrinos".

Using Elusive Particles

from

UniversityOfRochester Website

The message was sent through 240 meters of stone and said simply, "Neutrino."

Many have theorized about the possible uses of neutrinos in communication because of one particularly valuable property: they can penetrate almost anything they encounter.

If this technology could be applied to submarines, for instance, then they could conceivably communicate over long distances through water, which is difficult, if not impossible, with present technology.

And if we wanted to communicate with something in outer space that was on the far side of a moon or a planet, our message could travel straight through without impediment.

The team of scientists that demonstrated that it was possible performed their test at the Fermi National Accelerator Lab (or Fermilab, for short), outside of Chicago.

The group has submitted its findings (Demonstration

of Communication Using Neutrinos) to the journal

Modern Physics Letters A.

The second is a multi-ton detector

called

MINERvA,

located in a cavern 100 meters underground.

Neutrinos, on the other hand, regularly pass through entire planets without being disturbed.

Because of their neutral electric charge

and almost non-existent mass, neutrinos are not subject to magnetic

attractions and are not significantly altered by gravity, so they

are virtually free of impediments to their motion.

After the neutrinos were detected, a computer on the other end translated the binary code back into English, and the word "neutrino" was successfully received.

Minerva is an international collaboration of nuclear and particle physicists from 21 institutions that study neutrino behavior using a detector located at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory near Chicago.

This is the first neutrino experiment in the world to use a high-intensity beam to study neutrino reactions with nuclei of five different target materials, creating the first side-by-side comparison of interactions.

This will help complete the picture of neutrinos and allow data to be more clearly interpreted in current and future experiments.

|