|

by

Mike G.

October 17, 2014

from

DesmogBlog Website

Black smoke from burning of

associated gas

Image Credit: Leonid Ikan

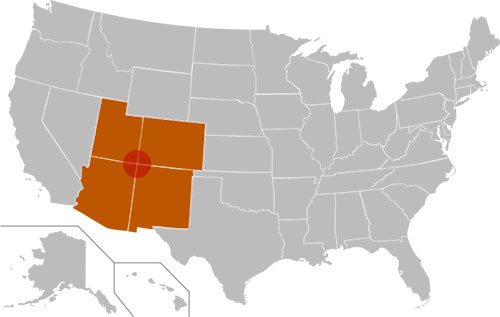

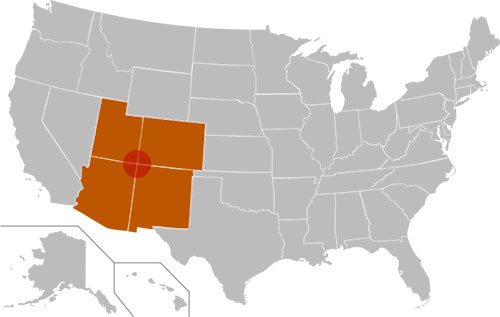

When NASA researchers first

saw data indicating a massive cloud of methane floating over the

American Southwest, they found it so incredible that they

dismissed it as an instrument error.

But as they continued analyzing data from the European Space

Agency’s Scanning Imaging Absorption Spectrometer for Atmospheric

Chartography (SCIAMACHY)

instrument from 2002 to 2012, the "atmospheric hot spot" kept

appearing.

The team at NASA was finally able to take

a closer look, and have now concluded that

there is in fact a 2,500-square-mile cloud of methane - roughly

the size of Delaware - floating over the Four Corners region

(below image), where the borders of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico,

and Utah all intersect.

A report published by the NASA researchers

in the journal Geophysical Research Letters (Four

Corners - The Largest U.S. Methane Anomaly Viewed from Space)

concludes that,

"the source is

likely from established gas, coal, and coal-bed methane mining

and processing."

Indeed, the hot spot happens to be above New Mexico's

San Juan Basin, the

most productive coalbed methane basin in North

America.

Methane is 20-times more potent as a greenhouse gas

than CO2, and has been

the focus of an increasing amount of attention, especially in

regards to

methane leaks from fracking for oil

and natural gas.

Pockets of natural gas, which is 95-98% methane, are

often found along with oil and simply burned off in a very visible

process called "flaring."

But scientists are starting to realize that far more

methane is being released by

the fracking boom than previously

thought.

Earlier this year, Cornell environmental engineering professor

Anthony Ingraffea released the results of a study of 41,000 oil

and gas wells (Assessment

and Risk Analysis of Casing and Cement Impairment in Oil and Gas

Wells in Pennsylvania)

that were drilled in Pennsylvania between 2000 and 2012, and

found newer wells using fracking and horizontal drilling methods

were far more likely to be responsible for fugitive emissions of

methane.

According to the NASA researchers, the

region of the American Southwest over which the 2,500-square-foot

methane cloud is floating emitted 590,000 metric tons of methane

every year between 2002 and 2012 - almost 3.5 times the widely used

estimates in the European Union’s

Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric

Research - and none of it was from fracking.

That should prompt a hard look at the entire fossil fuel sector, not

just fracking, according to University of Michigan Professor Eric

Kort, the lead researcher on the study:

"While fracking has become a focal point in

conversations about methane emissions, it certainly appears from

this and other studies that in the U.S.,

fossil fuel extraction activities across the board likely emit

higher than inventory estimates."

|