IN this chapter I shall try to show what effect the contact of a comet must have had upon the earth and its inhabitants.

I shall ask the reader to follow the argument closely first, that he may see whether any part of the theory is inconsistent with the well-established principles of natural philosophy; and, secondly, that he may bear the several steps in his memory, as he will find, as we proceed, that every detail of the mighty catastrophe has been preserved in the legends of mankind, and precisely in the order in which reason tells us they must have occurred.

In the first place, it is, of course, impossible at this time to say precisely how the contact took place; whether the head of the comet fell into or approached close to the sun, like the comet of 1843, and then swung its mighty tail, hundreds of millions of miles in length, moving at a rate almost equal to the velocity of light, around through a great are, and swept past the earth;--the earth, as it were, going through the midst of the tail, which would extend for a vast distance beyond and around it. In this movement, the side of the earth, facing the advance of the tail, would receive and intercept the mass of material--stones, gravel, and the finely-ground-up-dust which, compacted by water, is now clay--which came in contact with it, while the comet would sail off into space,

{p. 92}

demoralized, perhaps, in its orbit, like Lexell's comet when it became entangled with Jupiter's moons, but shorn of a comparatively small portion of its substance.

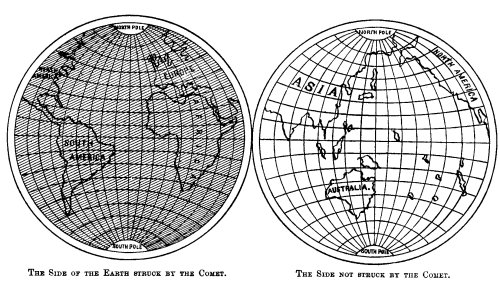

The following engraving will illustrate my meaning. I can not give, even approximately, the proportions of the

THE COMET SWEEPING PAST THE EARTH.

objects represented, and thus show the immensity of the sun as compared with our insignificant little orb. In a picture showing the true proportions of the sun and earth, the sun would have to be so large that it would take up the entire page, while the earth would be but as a

{p. 93}

THE SIDE OF THE EARTH STRUCK BY THE COMET {left}

THE SIDE NOT STRUCK BY THE COMET {right}

{p. 94}

pin-head. And I have not drawn the comet on a scale large enough as compared with the earth.

If the reader will examine the map on page 93, he will see that the distribution of the Drift accords with this theory. If we suppose the side of the earth shown in the left-hand figure was presented to the comet, we will see why the Drift is supposed to be confined to Europe, Africa, and parts of America; while the right-hand figure will show the half of the world that escaped.

"The breadth of the tail of the great comet of 1811, at its widest part, was nearly fourteen million miles, the length one hundred and sixteen million miles, and that of the second comet of the same year, one hundred and forty million miles."[1]

On page 95 is a representation of this monster.

Imagine such a creature as that, with a head fifty times as large as the moon, and a tail one hundred and sixteen million miles long, rushing past this poor little earth of ours, with its diameter of only seven thousand nine hundred and twenty-five miles! The earth, seven thousand nine hundred and twenty-five miles wide, would simply make a bullet-hole through that tail, fourteen million miles broad, where it passed through it!--a mere eyelet-hole--a pin-hole--closed up at once by the constant movements which take place in the tail of the comet. And yet in that moment of contact the side of the earth facing the comet might be covered with hundreds of feet of débris.

Or, on the other hand, the comet may, as described in some of the legends, have struck the earth, head on, amid-ships, and the shock may have changed the angle of inclination of the earth's axis, and thus have modified

[1. Schellen, "Spectrum Analysis," p. 392.]

{p. 95}

permanently the climate of our globe; and to this cause we might look also for the great cracks and breaks in the earth's surface, which constitute the fiords of the sea-coast and the trap-extrusions of the continents; and here, too,

THE GREAT COMET OF 1811.

might be the cause of those mighty excavations, hundreds of feet deep, in which are now the Great Lakes of America, and from which, as we have seen, great cracks radiate out in all directions, like the fractures in a pane of glass where a stone has struck it.

The cavities in which rest the Great Lakes have been attributed to the ice-sheet, but it is difficult to comprehend how an ice-sheet could dig out and root out a hole, as in the case of Lake Superior, nine hundred feet deep!

{p. 96}

And, if it did this, why were not similar holes excavated wherever there were ice-sheets--to wit, all over the northern and southern portions of the globe? Why should a general cause produce only local results?

Sir Charles Lyell shows[1] that glaciers do not cut out holes like the depressions in which the Great Lakes lie; he also shows that these lakes are not due to a sinking down of the crust of the earth, because the strata are continuous and unbroken beneath them. He also calls attention to the fact that there is a continuous belt of such lakes, reaching from the northwestern part of the United States, through the Hudson Bay Territory, Canada, and Maine, to Finland, and that this belt does not reach below 50° north latitude in Europe and 40° in America. Do these lie in the track of the great collision? The comet, as the striæ indicate, came from the north.

The mass of Donati's comet was estimated by MM. Faye and Roche at about the seven-hundredth part of the bulk of the earth. M. Faye says:

"That is the weight of a sea of forty thousand square miles one hundred and nine yards deep; and it must be owned that a like mass, animated with considerable velocity, might well produce, by its shock with the earth, very perceptible results."[2]

We have but to suppose, (a not unreasonable supposition,) that the comet which struck the earth was much larger than Donati's comet, and we have the means of accounting for results as prodigious as those referred to.

We have seen that it is difficult to suppose that ice produced the drift-deposits, because they are not found where ice certainly was, and they are found where ice certainly was not. But, if the reader will turn to the

[1. "Elements of Geology," pp. 168,171, et seq.

2. "The Heavens," p. 260.]

{p. 97}

illustration which constitutes the frontispiece of this volume, and the foregoing engraving on page 93, he will see that the Drift is deposited on the earth, as it might have been if it had suddenly fallen from the heavens; that is, it is on one side of the globe--to wit, the side that faced the comet as it came on. I think this map is substantially accurate. There is, however, an absence of authorities as to the details of the drift-distribution. But, if my theory is correct, the Drift probably fell at once. If it had been twenty-four hours in falling, the diurnal revolution would, in turn, have presented all sides of the earth to it, and the Drift would be found everywhere. And this is in accordance with what we know of the rapid movements of comets. They travel, as I have shown, at the rate of three hundred and sixty-six miles per second; this is equal to twenty-one thousand six hundred miles per minute, and one million two hundred and ninety-six thousand miles per hour!

And this accords with what we know of the deposition of the Drift. It came with terrific force. It smashed the rocks; it tore them up; it rolled them over on one another; it drove its material into the underlying rocks; "it indented it into them," says one authority, already quoted.

It was accompanied by inconceivable winds--the hurricanes and cyclones spoken of in many of the legends. Hence we find the loose material of the original surface gathered up and carried into the drift-material proper; hence the Drift is whirled about in the wildest confusion. Hence it fell on the earth like a great snow-storm driven by the wind. It drifted into all hollows; it was not so thick on, or it was entirely absent from, the tops of hills; it formed tails, precisely as snow does, on the leeward side of all obstructions. Glacier-ice is slow and plastic,

{p. 98}

and folds around such impediments, and wears them away; the wind does not. Compare the following representation of a well-known feature of the Drift, called

CRAG AND TAIL.--c, crag; t, till.

"crag and tail," taken from Geikie's work,[1] with the drifts formed by snow on the leeward side of fences or houses.

The material runs in streaks, just as if blown by violent winds:

"When cut through by rivers, or denuded by the action of the sea, ridges of bowlders are often seen to be inclosed within it. Although destitute of stratification, horizontal lines are found, indicating differences in texture and color."[2]

Geikie, describing the bowlder-clay, says:

"It seems to have come from regions whence it is bard to see how they could have been borne by glaciers. As a rule it is quite unstratified, but traces of bedding are not uncommon."

"Sometimes it contains worn fossils, and fragments of shells, broken, crushed, and striated; sometimes it contains bands of stones arranged in lines."

In short, it appears as if it were gusts and great whirls of the same material as the "till," lifted up by the cyclones and mingled with blocks, rocks, bones, sands, fossils, earth, peat, and other matters, picked up with terrible

[1. "The Great Ice Age," p. 18.

2. "American Cyclopædia," vol. vi, p. 112.]

{p. 99}

force from the face of the earth and poured down pell-mell on top of the first deposit of true "till."

In England ninety-four per cent of these stones found in this bowlder-clay are "stranger" stones; that is to say, they do not belong to the drainage area in which they are found, but must have been carried there from great distances.

But how about the markings, the striæ, on the face of the surface-rocks below the Drift? The answer is plain. Débris, moving at the rate of a million miles an hour, would produce just such markings.

Dana says:

"The sands carried by the winds when passing over rocks sometimes wear them smooth, or cover them with scratches and furrows, as observed by W. P. Blake on granite rocks at the Pass of San Bernardino, in California. Even quartz was polished and garnets were left projecting upon pedicels of feldspar. Limestone was so much worn as to look as if the surface had been removed by solution. Similar effects have been observed by Winchell in the Grand Traverse region, Michigan. Glass in the windows of houses on Cape Cod sometimes has holes worn through it by the same means. The hint from nature has led to the use of sand, driven by a blast, with or without steam, for cutting and engraving glass, and even for cutting and carving granite and other hard rocks."[1]

Gratacap describes the rock underneath the "till" as polished and oftentimes lustrous."[2]

But, it may be said, if it be true that débris, driven by a terrible force, could have scratched and dented the rocks, could it have made long, continuous lines and grooves upon them? But the fact is, the striæ on the face of the rocks covered by the Drift are not continuous;

[1. Dana's "Text-Book," p. 275.

2. "Popular Science Monthly," January, 1878, p. 320.]

{p. 100}

they do not indicate a steady and constant pressure, such as would result where a mountainous mass of ice had caught a rock and held it, as it were, in its mighty hand, and, thus holding it steadily, had scored the rocks with it as it moved forward.

"The groove is of irregular depth, its floor rising and falling, as though hitches had occurred when it was first planed, the great chisel meeting resistance, or being thrown up at points along its path."[1]

What other results would follow at once from contact with the comet?

We have seen that, to produce the phenomena of the Glacial age, it was absolutely necessary that it must have been preceded by a period of heat, great enough to vaporize all the streams and lakes and a large part of the ocean. And we have seen that no mere ice-hypothesis gives us any clew to the cause of this.

Would the comet furnish us with such heat? Let me call another witness to the stand:

In the great work of Amédée Guillemin, already cited, we read:

"On the other hand, it seems proved that the light of the comets is, in part, at least, borrowed from the sun. But may they not also possess a light of their own? And, on this last hypothesis, is this brightness owing to a kind of phosphorescence, or to the state of incandescence of the nucleus? Truly, if the nuclei of comets be incandescent, the smallness of their mass would eliminate from the danger of their contact with the earth only one element of destruction: the temperature of the terrestrial atmosphere would be raised to an elevation inimical to the existence of organized beings; and we should only escape the danger of a mechanical shock, to run into a not less frightful

[1. Gratacap, "The Ice Age," in "Popular Science Monthly," January, 1818, p. 321.]

{p. 101}

one of being calcined in a many days passage through an immense furnace."[1]

Here we have a good deal more heat than is necessary to account for that vaporization of the seas of the globe which seems to have taken place during the Drift Age.

But similar effects might be produced, in another way, even though the heat of the comet itself was inconsiderable.

Suppose the comet, or a large part of it, to have fallen into the sun. The arrested motion would be converted into heat. The material would feed the combustion of the sun. Some have theorized that the sun is maintained by the fall of cometic matter into it. What would be the result?

Mr. Proctor notes that in 1866 a star, in the constellation Northern Cross, suddenly shone with eight hundred times its former luster, afterward rapidly diminishing in luster. In 1876 a new star in the constellation Cygnus became visible, subsequently fading again so as to be only perceptible by means of a telescope; the luster of this star must have increased from five hundred to many thousand times.

Mr. Proctor claims that should our sun similarly increase in luster even one hundred-fold, the glowing heat would destroy all vegetable and animal life on earth.

There is no difficulty in seeing our way to heat enough, if we concede that a comet really struck the earth or fell into the sun. The trouble is in the other direction--we would have too much heat.

We shall see, hereafter, that there is evidence in our rocks that in two different ages of the world, millions of years before the Drift period, the whole surface of the

[1. "The Heavens," p. 260.]

{p. 102}

earth was actually fused and melted, probably by cometic contact.

This earth of ours is really a great powder-magazine there is enough inflammable and explosive material about it to blow it into shreds at any moment.

Sir Charles Lyell quotes, approvingly, the thought of Pliny: "It is an amazement that our world, so full of combustible elements, stands a moment unexploded."

It needs but an infinitesimal increase in the quantity of oxygen in the air to produce a combustion which would melt all things. In pure oxygen, steel burns like a candle-wick. Nay, it is not necessary to increase the amount of oxygen in the air to produce terrible results. It has been shown[1] that, of our forty-five miles of atmosphere, one fifth, or a stratum of nine miles in thickness, is oxygen. A shock, or an electrical or other convulsion, which would even partially disarrange or decompose this combination, and send an increased quantity of oxygen, the heavier gas, to the earth, would wrap everything in flames. Or the same effects might follow from any great change in the constitution of the water of the world. Water is composed of eight parts of oxygen and one part of hydrogen. "The intensest heat by far ever yet produced by the blow-pipe is by the combustion of these two gases." And Dr. Robert Hare, of Philadelphia, found that the combination which produced the intensest heat was that in which the two gases were in the precise proportions found in water.[2]

We may suppose that this vast heat, whether it came from the comet, or the increased action of the sun, preceded the fall of the débris of the comet by a few minutes or a few hours. We have seen the surface-rocks

[1. "Science and Genesis," p. 125.

2. Ibid., p. 127.]

{p. 103}

described as lustrous. The heat may not have been great enough to melt them--it may merely have softened them; but when the mixture of clay, gravel, striated rocks, and earth-sweepings fell and rested on them, they were at once hardened and almost baked; and thus we can account for the fact that the "till," which lies next to the rocks, is so hard and tough, compared with the rest of the Drift, that it is impossible to blast it, and exceedingly difficult even to pick it to pieces; it is more feared by workmen and contractors than any of the true rocks.

Professor Hartt shows that there is evidence that some cause, prior to but closely connected with the Drift, did decompose the surface-rocks underneath the Drift to great depths, changing their chemical composition and appearance. Professor Hartt says:

"In Brazil, and in the United States in the vicinity of New York city, the surface-rocks, under the Drift, are decomposed from a depth of a few inches to that of a hundred feet. The feldspar has been converted into slate, and the mica has parted with its iron."[1]

Professor Hartt tries to account for this metamorphosis by supposing it to have been produced by warm rains! But why should there be warm rains at this particular period? And why, if warm rains occurred in all ages, were not all the earlier rocks similarly changed while they were at the surface?

Heusser and Clarez suppose this decomposition of the rocks to be due to nitric acid. But where did the nitric acid come from?

In short, here is the proof of the presence on the earth, just before the Drift struck it, of that conflagration which we shall find described in so many legends.

[1. "The Geology of Brazil," p. 25.]

{p. 104}

And certainly the presence of ice could not decompose rocks a hundred feet deep, and change their chemical constitution. Nothing but heat could do it.

But we have seen that the comet is self-luminous--that is, it is in process of combustion; it emits great gushes and spouts of luminous gases; its nucleus is enveloped in a cloak of gases. What effect would these gases have upon our atmosphere?

First, they would be destructive to animal life. But it does not follow that they would cover the whole earth. If they did, all life must have ceased. They may have fallen in places here and there, in great sheets or patches, and have caused, until they burned themselves out, the conflagrations which the traditions tell us accompanied the great disaster.

Secondly, by adding increased proportions to some of the elements of our atmosphere they may have helped to produce the marked difference between the pre-glacial and our present climate.

What did these gases consist of?

Here that great discovery, the spectroscope, comes to our aid. By it we are able to tell the elements that are being consumed in remote stars; by it we have learned that comets are in part self-luminous, and in part shine by the reflected light of the sun; by it we are even able to identify the very gases that are in a state of combustion in comets.

In Schellen's great work[1] I find a cut (see next page) comparing the spectra of carbon with the light emitted by two comets observed in 1868--Winnecke's comet and Brorsen's comet.

Here we see that the self-luminous parts of these comets

[1. "Spectrum Analysis," p. 396.]

{p. 105}

burned with substantially the same spectrum as that emitted by burning carbon. The inference is irresistible that these comets were wrapped in great masses of carbon in a state of combustion. This is the conclusion reached by Dr. Schellen.

Padre Secchi, the great Roman astronomer, examined Dr. Winnecke's comet on the 21st of June, 1868, and concluded that the light from the self-luminous part was produced by carbureted hydrogen.

We shall see that the legends of the different races speak of the poison that accompanied the comet, and by which great multitudes were slain; the very waters that

{p. 106}

first flowed through the Drift, we are told, were poisonous. We have but to remember that carbureted hydrogen is the deadly fire-damp of the miners to realize what effect great gusts of it must have had on animal life.

We are told[1] that it burns with a yellow flame when subjected to great heat, and some of the legends, we will see hereafter, speak of the "yellow hair" of the comet that struck the earth.

And we are further told that, "when it, carbureted hydrogen, is mixed in due proportion with oxygen or atmospheric air, a compound is produced which explodes with the electric spark or the approach of flame." Another form of carbureted hydrogen, olefiant gas, is deadly to life, burns with a white light, and when mixed with three or four volumes of oxygen, or ten or twelve of air, it explodes with terrific violence.

We shall see, hereafter, that many of the legends tell us that, as the comet approached the earth, that is, as it entered our atmosphere and combined with it, it gave forth world-appalling noises, thunders beyond all earthly thunders, roarings, howlings, and hissings, that shook the globe. If a comet did come, surrounded by volumes of carbureted hydrogen, or carbon combined with hydrogen, the moment it reached far enough into our atmosphere to supply it with the requisite amount of oxygen or atmospheric air, precisely such dreadful explosions would occur, accompanied by noises similar to those described in the legends.

Let us go a step further:

Let us try to conceive the effects of the fall of the material of the comet upon the earth.

We have seen terrible rain-storms, hail-storms, snow-storms;

[1. "American Cyclopædia," vol. iii, p. 776.]

{p. 107}

but fancy a storm of stones and gravel and clay-dust!--not a mere shower either, but falling in black masses, darkening the heavens, vast enough to cover the world in many places hundreds of feet in thickness; leveling valleys, tearing away and grinding down hills, changing the whole aspect of the habitable globe. Without and above it roars the earthquaking voice of the terrible explosions; through the drifts of débris glimpses are caught of the glaring and burning monster; while through all and over all is an unearthly heat, under which rivers, ponds, lakes, springs, disappear as if by magic.

Now, reader, try to grasp the meaning of all this description. Do not merely read the words. To read aright, upon any subject, you must read below the words, above the words, and take in all the relations that surround the words. So read this record.

Look out at the scene around you. Here are trees fifty feet high. Imagine an instantaneous descent of granite-sand and gravel sufficient to smash and crush these trees to the ground, to bury their trunks, and to cover the earth one hundred to five hundred feet higher than the elevation to which their tops now reach! And this not alone here in your garden, or over your farm, or over your township, or over your county, or over your State; but over the whole continent in which you dwell--in short, over the greater part of the habitable world!

Are there any words that can draw, even faintly, such a picture--its terror, its immensity, its horrors, its destructiveness, its surpassal of all earthly experience and imagination? And this human ant-hill, the world, how insignificant would it be in the grasp of such a catastrophe! Its laws, its temples, its libraries, its religions, its armies, its mighty nations, would be but as the veriest

{p. 108}

stubble--dried grass, leaves, rubbish-crushed, smashed, buried, under this heaven-rain of horrors.

But, lo! through the darkness, the wretches not beaten down and whelmed in the débris, but scurrying to mountain-caves for refuge, have a new terror: the cry passes from lip to lip, "The world is on fire!"

The head of the comet sheds down fire. Its gases have fallen in great volumes on the earth; they ignite; amid the whirling and rushing of the débris, caught in cyclones, rises the glare of a Titanic conflagration. The winds beat the rocks against the rocks; they pick up sand-heaps, peat-beds, and bowlders, and whirl them madly in the air. The heat increases. The rivers, the lakes, the ocean itself, evaporate.

And poor humanity! Burned, bruised, wild, crazed, stumbling, blown about like feathers in the hurricanes, smitten by mighty rocks, they perish by the million; a few only reach the shelter of the caverns; and thence, glaring backward, look out over the ruins of a destroyed world.

And not humanity alone has fled to these hiding-places: the terrified denizens of the forest, the domestic animals of the fields, with the instinct which in great tempests has driven them into the houses of men, follow the refugees into the caverns. We shall see all this depicted in the legends.

The first effect of the great heat is the vaporization of the waters of the earth; but this is arrested long before it has completed its work.

Still the heat is intense--how long it lasts, who shall tell? An Arabian legend indicates years.

The stones having ceased to fall, the few who have escaped--and they are few indeed, for many are shut up for ever by the clay-dust and gravel in their hiding-places,

{p. 109}

and on many others the convulsions of the earth have shaken down the rocky roofs of the caves--the few survivors come out, or dig their way out, to look upon a changed and blasted world. No cloud is in the sky, no rivers or lakes are on the earth; only the deep springs of the caverns are left; the sun, a ball of fire, glares in the bronze heavens. It is to this period that the Norse legend of Mimer's well, where Odin gave an eye for a drink of water, refers.

But gradually the heat begins to dissipate. This is a signal for tremendous electrical action. Condensation commences. Never has the air held such incalculable masses of moisture; never has heaven's artillery so rattled and roared since earth began! Condensation means clouds. We will find hereafter a whole body of legends about "the stealing of the clouds" and their restoration. The veil thickens. The sun's rays are shut out. It grows colder; more condensation follows. The heavens darken. Louder and louder bellows the thunder. We shall see the lightnings represented, in myth after myth, as the arrows of the rescuing demi-god who saves the world. The heat has carried up perhaps one fourth of all the water of the world into the air. Now it is condensed into cloud. We know how an ordinary storm darkens the heavens. In this case it is black night. A pall of dense cloud, many miles in thickness, enfolds the earth. No sun, no moon, no stars, can be seen. "Darkness is on the face of the deep." Day has ceased to be. Men stumble against each other. All this we shall find depicted in the legends. The overloaded atmosphere begins to discharge itself. The great work of restoring the waters of the ocean to the ocean begins. It grows colder--colder--colder. The pouring rain turns into snow, and settles on all the uplands and north countries; snow falls on

{p. 110}

snow; gigantic snow-beds are formed, which gradually solidify into ice. While no mile-thick ice-sheet descends to the Mediterranean or the Gulf of Mexico, glaciers intrude into all the valleys, and the flora and fauna of the temperate regions become arctic; that is to say, only those varieties of plants and animals survive in those regions that are able to stand the cold, and these we now call arctic.

In the midst of this darkness and cold and snow, the remnants of poor humanity wander over the face of the desolated world; stumbling, awe-struck, but filled with an insatiable hunger which drives them on; living upon the bark of the few trees that have escaped, or on the bodies of the animals that have perished, and even upon one another.

All this we shall find plainly depicted in the legends of mankind, as we proceed.

Steadily, steadily, steadily--for days, weeks, months, years--the rains and snows fall; and, as the clouds are drained, they become thinner and thinner, and the light increases.

It has now grown so light that the wanderers can mark the difference between night and day. "And the evening and the morning were the first day."

Day by day it grows lighter and warmer; the piled-up snows begin to melt. It is an age of tremendous floods. All the low-lying parts of the continents are covered with water. Brooks become mighty rivers, and rivers are floods; the Drift débris is cut into by the waters, re-arranged, piled up in what is called the stratified, secondary, or Champlain drift. Enormous river-valleys are cut out of the gravel and clay.

The seeds and roots of trees and grasses, uncovered by the rushing torrents, and catching the increasing

{p. 111}

warmth, begin to put forth green leaves. The sad and parti-colored earth, covered with white, red, or blue clays and gravels, once more, wears a fringe of green.

The light increases. The warmth lifts up part of the water already cast down, and the outflow of the steaming ice-fields, and pours it down again in prodigious floods. It is an age of storms.

The people who have escaped gather together. They know the sun is coming back. They know this desolation is to pass away. They build great fires and make human sacrifices to bring back the sun. They point and guess where he will appear; for they have lost all knowledge of the cardinal points. And all this is told in the legends.

At last the great, the godlike, the resplendent luminary breaks through the clouds and looks again upon the wrecked earth.

Oh, what joy, beyond all words, comes upon those who see him! They fall upon their faces. They worship him whom the dread events have taught to recognize as the great god of life and light. They burn or cast down their animal gods of the pre-glacial time, and then begins that world-wide worship of the sun which has continued down to our own times.

And all this, too, we shall find told in the legends.

And from that day to this we live under the influence of the effects produced by the comet. The mild, eternal summer of the Tertiary age is gone. The battle between the sun and the ice-sheets continues. Every north wind brings us the breath of the snow; every south wind is part of the sun's contribution to undo the comet's work. A continual amelioration of climate has been going on since the Glacial age; and, if no new catastrophe falls on the earth, our remote posterity will yet see the last snow-bank

{p. 112}

of Greenland melted, and the climate of the Eocene reestablished in Spitzbergen.

"It has been suggested that the warmth of the Tertiary climate was simply the effect of the residual heat of a globe cooling from incandescence, but many facts disprove this. For example, the fossil plants found in our Lower Cretaceous rocks in Central North America indicate a temperate climate in latitude 35° to 40° in the Cretaceous age. The coal-flora, too, and the beds of coal, indicate a moist, equable, and warm but not hot climate in the Carboniferous age, millions of years before the Tertiary, and three thousand miles farther south than localities where magnolias, tulip-trees, and deciduous cypresses, grew in the latter age. Some learned and cautious geologists even assert that there have been several Ice periods, one as far back as the Devonian."[1]

The ice-fields and wild climate of the poles, and the cold which descends annually over Europe and North America, represent the residuum of the refrigeration caused by the evaporation due to the comet's heat, and the long absence of the sun during the age of darkness. Every visitation of a comet would, therefore, necessarily eventuate in a glacial age, which in time would entirely pass away. And our storms are bred of the conflict between the heat and cold of the different latitudes. Hence, it may be, that the Tertiary climate represented the true climate of the earth, undisturbed by comet catastrophes; a climate equable, mild, warm, stormless. Think what a world this would be without tempests, cyclones, ice, snow, or cold!

Let us turn now to the evidences that man dwelt on the earth during the Drift, and that he has preserved recollections of the comet to this day in his myths and legends.

[1. "Popular Science Monthly," July, 1876, p. 283.]

{p. 113}

Next: Part III. The Legends.--Chapter I. The Nature Of Myths