|

Empire Strikes Back

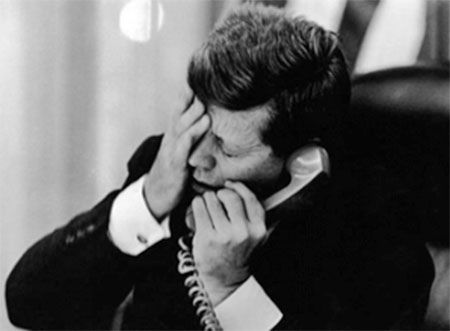

JFK learns that Lumumba has been killed.

Little is Ever What it Seems

It seems that he had been involved in

intelligence work for much of his adult life. He had been in and around hot

spots of covert action. And in the fall of 1963, he had for some

unfathomable reason been worried that someone would discover he had been in

Dallas on the evening of November 21 and seemingly the morning of November

22.

Why hide that fact?

But given his documented intelligence ties and

the fact that figures close to him were connected to the event, the

likelihood that his attempt to distance himself from Dallas on November 22

was unrelated to the tragedy of that day seems low.

In the absence of any plausible alternative explanation, I found the possibility that George H. W. Bush himself was somehow linked to the events in Dallas worth pursuing, as a working hypothesis at least.

Among the material I had to consider was that memo from J. Edgar Hoover referring to a briefing given to "George Bush of the CIA" on the day after the assassination.

I also had to take into account the visit from

England that week by Al Ulmer, the CIA coup expert - and that Ulmer

had spent time with Poppy. There were still more disturbing facts, perhaps

all coincidental, which I gathered and which will be presented below and in

the next chapter.

But I knew I should not, and really could not

ignore what I was finding.

Heads had rolled, and Allen Dulles, the Bushes’ close friend, was still smarting over his firing.

So was Charles Cabell, the brother of Dallas

mayor Earle Cabell and the CIA’s deputy director of operations during the

Bay of Pigs invasion; Kennedy deep-sixed his career. Also holding a grudge

against the Kennedys was Prescott Bush, who was furious at both JFK and RFK

for sacking his close friend Dulles. And there were many others.

In Poppy’s book-length collection of correspondence, All the Best, George Bush, there are no letters in the relevant time frame even mentioning the JFK assassination.

Remarkably for a Texan, and an aspiring Texas politician of that era, Bush has apparently never written anything about the assassination. This applies even to his anemic memoir, Looking Forward, in which he mentions Kennedy’s visit to Dallas but not what happened to him there.

Once I began to piece together the scattered clues to what might be the true narrative, I realized that Poppy’s resort to crafty evasions and multilayered cover stories in this incident seemed to fit a pattern in his life.

Over and over, those seeking to nail down the

facts about George H. W. Bush’s doings encounter what might be characterized

as a sustained fuzziness; what appear at first glance to be unexceptionable

details turn out, on closer examination, to be potentially important facts

that slip away into confusion and deniability. Little is ever what it seems.

We start with motive.

Jack’s insistence on Allen Dulles’s resignation following the Bay of Pigs debacle was in effect a declaration of independence from the Wall Street intelligence nexus that had pretty much had its way in the previous administration. Like FDR, JFK was considered a traitor to his own class.

Also like FDR, he had the charm and political savvy to get away with it. With his wealthy scoundrel of a father in his corner, he could not be bought or controlled.

After Castro announced in December 1959 that he

was a Communist, the CIA recognized its newly found common cause with the

underworld and solicited the services of several mobsters, in what became

the notorious CIA-Mafia plots against JFK. There was motive aplenty:

Attorney General Robert Kennedy relentlessly pursued the mob-tied Teamsters

boss Jimmy Hoffa and a long list of underworld figures.

For one thing, Jack Kennedy could not keep his

pants on. He thought nothing of romancing the wives and girlfriends of the

powerful. The FBI tracked many affairs during JFK’s brief time in office,

but then J. Edgar Hoover was no fan of the Kennedys either.

But he became increasingly wary of the nation’s war machine, especially after the Cuban missile crisis.

During those tense days, as the nation seemed to drift toward nuclear confrontation, and his military advisers pushed for a preemptive first strike against the missile sites in Cuba, Kennedy had turned to his adviser Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and said,

He preferred a negotiated solution for getting

the missiles out of Cuba, and he and Khrushchev eventually reached one. This

gained them world-wide praise, but it exacerbated tensions for both men with

hard-liners in their own countries.

President Kennedy was aware that the Pentagon was deeply concerned about his policies.

After reading Seven Days in May, a novel about a coup by U.S. armed forces against a president seen as an appeaser, he convinced John Frankenheimer to make it into a movie. JFK even offered the director a prime shooting location outside the White House - in spite of vociferous objections from the Pentagon.

President Kennedy also alienated critics over Indochina. Historians still debate JFK’s long-term plans regarding troop levels there, but he clearly worried about a looming quagmire.

Here, too, the lessons of the Bay of Pigs applied: the United States could not win without the support of the local populace. Anti-Communist hawks were skeptical of Kennedy’s motives. Some even issued preemptive warnings:

Kennedy’s economic policies were drawing additional heat. In Latin America, for example, he antagonized American businessmen, including Nelson Rockefeller, when he interfered with their oil and mineral plans in Brazil’s vast Amazon basin.

On June 10, 1963, in a speech at American University in Washington, D.C., the president took a direct shot at the military-industrial complex by announcing support for the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited aboveground and underwater nuclear weapons tests.

Kennedy had been stunned to learn of the human cost of radioactive fallout.

But the nuclear arms race was another bonanza for business - uranium-mining operations in particular.

These constituted a growing share of earnings for the oil exploration and resource extraction industry.

(Decades later, the

George W. Bush-Dick Cheney administration would pull the United

States out of the treaty regime that had begun with the Test Ban Treaty.

This would be just one of many instances in which the younger Bush fulfilled

objectives long harbored by Kennedy’s right-wing enemies.)

It was a combustible mix.

It was more like New Orleans - spectacularly corrupt, and with forceful elements, from the genteel to the unwashed, jockeying for power. The police force included KKK members and habitués of gangster redoubts such as Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club.

Yet Dallas also was a growing bastion of new money and corporate clout, a center of the domestic oil industry, along with a heavy clustering of defense contractors and military bases.

Texas was in a sense a feisty breakaway republic with a complicit colony of transplants from the Eastern Establishment.

Texas oil riches and Eastern entitlement, combined with the mix of intelligence and defense, gave rise to an atmosphere of intrigue.

The established energy giants had long relied on corporate covert operations to help maintain their far-flung oil empires. Now independent producers and refiners were getting into this game as well; and the mind-set tended to spill over into politics.

A 1964 New York Times article reported on a group of businessmen who had formed,

The group was powerful and confident enough that it essentially advertised the fact that anyone seeking project approval should come to it, rather than the official government agencies.

Politically, the members of this new establishment,

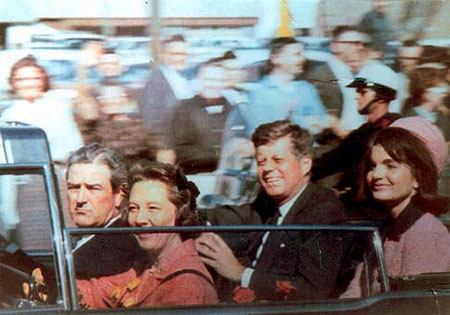

The Kennedys understood the political importance of Dallas, and of Texas in general.

They chose Lyndon Johnson, a fierce competitor for the nomination in 1960, to be Jack’s vice president because they needed Southern, in particular Texan, votes. After the election, they appointed Texans, like John Connally, a lawyer representing oil interests, to be secretary of the Navy, and George McGhee, the son-in-law of Everette DeGolyer, the legendary oil industry figure, as deputy secretary of state.

But political accommodation does not necessarily

bring affection. Dallas still was not a friendly place for JFK.

While Prescott Bush and Allen Dulles remained anchored in the East, Poppy and "Uncle" Neil Mallon had done well in Houston and Dallas, respectively. Mallon nurtured the de facto power structure emerging in Dallas, most of which worked out of one particular Dallas high-rise, the Republic National Bank Building.

A Kennedy rally would not have attracted many

people from there, and not for reasons of ideology alone.

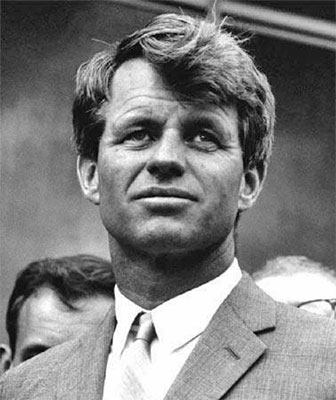

Where Jack was charming, Bobby was blunt. Where Jack was cautious, Bobby was aggressive. Bobby’s innumerable investigations into fraud and corruption among military contractors, politicians, and corporate eminences - including a Greek shipping magnate named Aristotle Onassis - made many enemies.

His determination to take on organized crime angered FBI director Hoover, who had long-standing friendships with mob associates and enjoyed spending time at resorts and racetracks in the company of these individuals. Hoover routinely bypassed the Kennedys and dealt with Vice President Johnson instead.

In fact, the Kennedys were hoping that after the

1964 election, they would have the clout to finally retire Hoover, who had

headed the FBI since its inception four decades before.

But Kennedy’s gutsiest - and arguably his most dangerous - domestic initiative was his administration’s crusade against the oil depletion allowance, the tax break that swelled uncounted oil fortunes. It gave oil companies a large and automatic deduction, regardless of their actual costs, as compensation for dwindling assets in the ground.

Robert Kennedy instructed the FBI to issue

questionnaires, asking the oil companies for specific production and sales

data.

FBI director Hoover expressed his own reservations, especially about the use of his agents to gather information in the matter.

Hoover’s close relationship with the oil

industry was part of the oil-intelligence link he shared with Dulles and the

CIA. Industry big shots weren’t just sources; they were clients and friends.

And Hoover’s FBI was known for returning favors.

Another strong defender of the allowance was Democratic senator Robert Kerr of Oklahoma, the multimillionaire owner of the Kerr-McGee oil company.

So friendly was he with his Republican colleague

Prescott Bush that when Poppy Bush was starting up his Zapata Offshore

operation, Kerr offered some of his own executives to help. Several of them

even left Kerr’s company to become Bush’s top executives.

Although the former haberdasher would publicly

exhibit some independence, he often buckled privately to Kerr and his

like-minded friends. One example was Truman’s decision to create the

nation’s first true peacetime spy apparatus, which eventually became the

Central Intelligence Agency.

Even among a cutthroat Washington crowd, Robert Kerr’s vicious side stood out - and he did not much like the Kennedys. As an old friend and mentor to LBJ, Kerr had been so angry on learning that Johnson had accepted the number-two spot under Jack Kennedy that he was ready to start shooting.

Wheeling on Johnson, his wife, Lady Bird, and Johnson aide Bobby Baker, Kerr yelled:

In fact, he was the one person in the White House the oilmen trusted. The Kennedys, for their part, had never like LBJ - he had run hard against Jack in the 1960 primaries. They asked him to be Jack’s running mate for political purposes alone. Within a year of the inauguration, there was already talk of dumping him in 1964. RFK, in particular, detested Johnson, and the feeling was mutual.

RFK’s investigations of military contractors in

Texas increasingly pointed towards a network of corruption that might well

lead back to LBJ himself. According to presidential historian Robert

Dallek,

While in law school in Austin, the Liedtkes had rented the servants’ quarters of Johnson’s home. (At the time, the main house was occupied by future Democratic governor John Connally, a protégé of Johnson’s.) Another connection came through Senator Prescott Bush, whose conservative Republican values often dovetailed with those of Johnson during the years when LBJ served as the Democrats’ majority leader.

After Johnson ascended to the presidency, he and

newly elected congressman Poppy Bush were often allies on such issues as the

oil depletion allowance and the war in Vietnam.

Whether one was nominally a Democrat or Republican did not much matter.

They all shared an enthusiasm for the anything-goes capitalism that had made them rich, and a deep aversion to what was known in the local dialect as "government inference."

That meant anything the government did - such as environmental rules or antitrust investigations - that did not constitute a favor or bestowal.

on the cover of his biography

by Lon Tinkle

His name was Everette DeGolyer, and he and his son-in-law George McGhee represented, to a unique degree, the ongoing influence that the oil industry has had on the White House, irrespective of the occupant. They were also allies of the Bushes.

In addition to his consulting firm DeGolyer-MacNaughton, DeGolyer founded Geophysical Service Inc., which later became Texas Instruments, and was a pioneer in technologies that became central to the industry, such as aerial exploration and the use of seismographic equipment in prospecting.

His career spanned the terms of eight American presidents, many of whom he knew; he was also on close terms with many Anglo-European oil figures and leaders of the Arab world. He sat on the board of Dresser Industries for many years, and, as we shall see in chapter 13, played a central role in cementing the U.S.-Saudi oil relationship.

Until he died in 1956, DeGolyer was the man you

went to if you wanted to get into the oil and gas game. The intelligence

agencies sought him out as well.

McGhee also sat on the board of James and William Buckley’s family firm, Pantepec Oil, which employed George de Mohrenschildt, whom McGhee knew personally.

Both McGhee and de Mohrenschildt were active in Neil Mallon’s Dallas Council on World Affairs.

After the war, McGhee served as assistant secretary of state for Near East affairs.

In 1951 he spent eighty hours at the bedside of Iran’s prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh in an attempt to mediate the terms of ownership for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.

Two years after their unsuccessful talks, Mossadegh was overthrown in a CIA-led coup. Time and again, McGhee,

George McGhee

When LBJ became vice president, he oversaw McGhee’s appointment as undersecretary of state for political affairs. McGhee’s elevation to one of the top posts in the State Department particularly annoyed Robert Kennedy, who managed to get him reassigned as ambassador to West Germany.

McGee "was useless," said RFK.

Needless to say, McGhee did not become a member

of the Bobby Kennedy fan club.

And even worse was the prospect that the Kennedys could become a dynasty.

After Jack there might be Bobby, and after

Bobby, Ted. It was not an appealing prospect to the Bushes and their circle;

and it is only stating the obvious to observe that this was not a group to

suffer setbacks with a fatalistic shrug.

Instead, within a dozen years of Bobby Kennedy’s

assassination, a new conservative dynasty was beginning to emerge: the House

of Bush.

We want to believe in our institutions and in the order they embody. It is unnerving to even consider the possibility that the most powerful among us might deem themselves exempt from the rules in such a fundamental way. Yet, the leaders of these same institutions have frequently seen nothing wrong with assassinating leaders in other countries, even democratically elected ones.

The CIA condoned, connived at, or indeed took an active role in assassination plots and coups against figures as varied as,

Is it that difficult to believe that those who

viewed assassination as a policy tool would use it at home, where the sense

of grievance and the threat to their interests was even greater?

As the Washington Post wrote in McGhee’s obituary:

Some years before McGhee’s death, a JFK assassination researcher asked him in writing if he had had a role in Trujillo’s death.

McGhee wrote back that while he had not, the assassination "was not a problem for me."

|