|

PART ONE

“In Khazaria, sheep, honey, and Jews exist in large quantities.”

I - RISE

The Byzantine Emperor and historian, Constantine Porphyrogenitus (913-959), must have been well aware of this when he recorded in his treatise on court protocol that letters addressed to the Pope in Rome, and similarly those to the Emperor of the West, had a gold seal worth two solidi attached to them, whereas messages to the King of the Khazars displayed a seal worth three solidi. This was not flattery, but Realpolitik. “In the period with which we are concerned,” wrote Bury, “it is probable that the Khan of the Khazars was of little less importance in view of the imperial foreign policy than Charles the Great and his successors.” The country of the Khazars, a people of Turkish stock, occupied a strategic key position at the vital gateway between the Black Sea and the Caspian, where the great eastern powers of the period confronted each other. It acted as a buffer protecting Byzantium against invasions by the lusty barbarian tribesmen of the northern steppes — Bulgars, Magyars, Pechenegs, etc. — and, later, the Vikings and the Russians.

But equally, or even more important both from the point of view of Byzantine diplomacy and of European history, is the fact that the Khazar armies effectively blocked the Arab avalanche in its most devastating early stages, and thus prevented the Muslim conquest of Eastern Europe. Professor Dunlop of Columbia University, a leading authority on the history of the Khazars, has given a concise summary of this decisive yet virtually unknown episode:

It is perhaps not surprising, given these circumstances, that in 732 — after a resounding Khazar victory over the Arabs — the future Emperor Constantine V married a Khazar princess. In due time their son became the Emperor Leo IV, known as Leo the Khazar. Ironically, the last battle in the war, AD 737, ended in a Khazar defeat. But by that time the impetus of the Muslim Holy War was spent, the Caliphate was rocked by internal dissensions, and the Arab invaders retraced their steps across the Caucasus without having gained a permanent foothold in the north, whereas the Khazars became more powerful than they had previously been. A few years later, probably AD 740, the King, his court and the military ruling class embraced the Jewish faith, and Judaism became the state religion of the Khazars.

No doubt their contemporaries were as astonished by this decision as modern scholars were when they came across the evidence in the Arab, Byzantine, Russian and Hebrew sources. One of the most recent comments is to be found in a work by the Hungarian Marxist historian, Dr Antal Bartha. His book on The Magyar Society in the Eighth and Ninth Centuries has several chapters on the Khazars, as during most of that period the Hungarians were ruled by them. Yet their conversion to Judaism is discussed in a single paragraph, with obvious embarrassment. It reads:

Which leaves us only slightly more bewildered than before. Yet whereas the sources differ in minor detail, the major facts are beyond dispute. What is in dispute is the fate of the Jewish Khazars after the destruction of their empire, in the twelfth or thirteenth century. On this problem the sources are scant, but various late mediaeval Khazar settlements are mentioned in the Crimea, in the Ukraine, in Hungary, Poland and Lithuania. The general picture that emerges from these fragmentary pieces of information is that of a migration of Khazar tribes and communities into those regions of Eastern Europe — mainly Russia and Poland — where, at the dawn of the Modern Age, the greatest concentrations of Jews were found.

This has lead several historians to conjecture that a substantial part, and perhaps the majority of eastern Jews — and hence of world Jewry — might be of Khazar, and not of Semitic Origin. The far-reaching implications of this hypothesis may explain the great caution exercised by historians in approaching this subject — if they do not avoid it altogether. Thus in the 1973 edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica the article “Khazars” is signed by Dunlop, but there is a separate section dealing with “Khazar Jews after the Fall of the Kingdom”, signed by the editors, and written with the obvious intent to avoid upsetting believers in the dogma of the Chosen Race:

Thus Cassel, a nineteenth-century orientalist, implying that the Khazars shared, for similar reasons, a similar fate. Yet the Hun presence on the European scene lasted a mere eighty years, whereas the kingdom of the Khazars held its own for the best part of four centuries. They too lived chiefly in tents, but they also had large urban settlements, and were in the process of transformation from a tribe of nomadic warriors into a nation of farmers, cattle-breeders, fishermen, vine-growers, traders and skilled craftsmen. Soviet archaeologists have unearthed evidence for a relatively advanced civilization which was altogether different from the “Hun whirlwind”.

They found the traces of villages extending over several miles, with houses connected by galleries to huge cattlesheds, sheep-pens and stables (these measured 3-3½ x 10-14 meters and were supported by columns. Some remaining ox-ploughs showed remarkable craftsmanship; so did the preserved artifacts — buckles, clasps, ornamental saddle plates. Of particular interest were the foundations, sunk into the ground, of houses built in a circular shape. According to the Soviet archaeologists, these were found all over the territories inhabited by the Khazars, and were of an earlier date than their “normal”, rectangular buildings.

Obviously the round-houses symbolize the transition from portable, dome-shaped tents to permanent dwellings, from the nomadic to a settled, or rather semi-settled, existence. For the contemporary Arab sources tell us that the Khazars only stayed in their towns — including even their capital, Itil — during the winter; come spring, they packed their tents, left their houses and sallied forth with their sheep or cattle into the steppes, or camped in their cornfields or vineyards. The excavations also showed that the kingdom was, during its later period, surrounded by an elaborate chain of fortifications, dating from the eighth and ninth centuries, which protected its northern frontiers facing the open steppes.

These fortresses formed a rough semi-circular arc from the Crimea (which the Khazars ruled for a time) across the lower reaches of the Donetz and the Don to the Volga; while towards the south they were protected by the Caucasus, to the west by the Black Sea, and to the east by the “Khazar Sea”, the Caspian. However, the northern chain of fortifications marked merely an inner ring, protecting the stable core of the Khazar country; the actual boundaries of their rule over the tribes of the north fluctuated according to the fortunes of war.

At the peak of their power they controlled or exacted tribute from some thirty different nations and tribes inhabiting the vast territories between the Caucasus, the Aral Sea, the Ural Mountains, the town of Kiev and the Ukrainian steppes. The people under Khazar suzerainty included the Bulgars, Burtas, Ghuzz, Magyars (Hungarians), the Gothic and Greek colonies of the Crimea, and the Slavonic tribes in the north-western woodlands. Beyond these extended dominions, Khazar armies also raided Georgia and Armenia and penetrated into the Arab Caliphate as far as Mosul. In the words of the Soviet archaeologist M. I. Artamonov:

Taking a bird’s-eye view of the history of the great nomadic empires

of the East, the Khazar kingdom occupies an intermediary position in

time, size, and degree of civilization between the Hun and Avar

Empires which preceded, and the Mongol Empire that succeeded it.

After a century of warfare, the Arab writer obviously had no great sympathy for the Khazars. Nor had the Georgian or Armenian scribes, whose countries, of a much older culture, had been repeatedly devastated by Khazar horsemen. A Georgian chronicle, echoing an ancient tradition, identifies them with the hosts of Gog and Magog — “wild men with hideous faces and the manners of wild beasts, eaters of blood”.

An Armenian writer refers to “the horrible multitude of Khazars with insolent, broad, lashless faces and long falling hair, like women”. Lastly, the Arab geographer Istakhri, one of the main Arab sources, has this to say:

This is more flattering, but only adds to the confusion. For it was customary among Turkish peoples to refer to the ruling classes or clans as “white”, to the lower strata as “black”.

Thus there is no reason to believe that the “White Bulgars” were whiter than the “Black Bulgars”, or that the “White Huns” (the Ephtalites) who invaded India and Persia in the fifth and sixth centuries were of fairer skin than the other Hun tribes which invaded Europe. Istakhri’s black-skinned Khazars — as much else in his and his colleagues’ writings — were based on hearsay and legend; and we are none the wiser regarding the Khazars’ physical appearance, or their ethnic Origins. The last question can only be answered in a vague and general way.

But it is equally frustrating to inquire into the origins of the Huns, Alans, Avars, Bulgars, Magyars, Bashkirs, Burtas, Sabirs, Uigurs, Saragurs, Onogurs, Utigurs, Kutrigurs, Tarniaks, Kotragars, Khabars, Zabenders, Pechenegs, Ghuzz, Kumans, Kipchaks, and dozens of other tribes or people who at one time or another in the lifetime of the Khazar kingdom passed through the turnstiles of those migratory playgrounds.

Even the Huns, of whom we know much more, are of uncertain origin; their name is apparently derived from the Chinese Hiung-nu, which designates warlike nomads in general, while other nations applied the name Hun in a similarly indiscriminate way to nomadic hordes of all kinds, including the “White Huns” mentioned above, the Sabirs, Magyars and Khazars. In the first century AD, the Chinese drove these disagreeable Hun neighbours westward, and thus started one of those periodic avalanches which swept for many centuries from Asia towards the West. From the fifth century onward, many of these westward-bound tribes were called by the generic name of “Turks”.

The term is also supposed to be of Chinese origin (apparently derived from the name of a hill) and was subsequently used to refer to all tribes who spoke languages with certain common characteristics — the “Turkic” language group. Thus the term Turk, in the sense in which it was used by mediaeval writers — and often also by modern ethnologists — refers primarily to language and not to race. In this sense the Huns and Khazars were “Turkic” people. The Khazar language was supposedly a Chuvash dialect of Turkish, which still survives in the Autonomous Chuvash Soviet Republic, between the Volga and the Sura. The Chuvash people are actually believed to be descendants of the Bulgars, who spoke a dialect similar to the Khazars.

But all these connections are rather tenuous, based on the more or less speculative deductions of oriental philologists. All we can say with safety is that the Khazars were a “Turkic” tribe, who erupted from the Asian steppes, probably in the fifth century of our era. The origin of the name Khazar, and the modern derivations to which it gave rise, has also been the subject of much ingenious speculation. Most likely the word is derived from the Turkish root gaz, “to wander”, and simply means “nomad”.

Of greater interest to the non-specialist are some alleged

modern derivations from it: among them the Russian Cossack and the

Hungarian Huszar — both signifying martial horsemen; and also the

German Ketzer — heretic, i.e., Jew. If these derivations are

correct, they would show that the Khazars had a considerable impact

on the imagination of a variety of peoples in the Middle Ages.

It mentions the Khazars in a list of people who inhabit the region of the Caucasus. Other sources indicate that they were already much in evidence a century earlier, and intimately connected with the Huns. In AD 448, the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II sent an embassy to Attila which included a famed rhetorician by name of Priscus. He kept a minute account not only of the diplomatic negotiations, but also of the court intrigues and goings-on in Attila’s sumptuous banqueting hall — he was in fact the perfect gossip columnist, and is still one of the main sources of information about Hun customs and habits.

But Priscus also has anecdotes to tell about a people subject to the Huns whom he calls Akatzirs — that is, very likely, the Ak-Khazars, or “White” Khazars (as distinct from the “Black” Kara-Khazars). The Byzantine Emperor, Priscus tells us, tried to win this warrior race over to his side, but the greedy Khazar chieftain, named Karidach, considered the bribe offered to him inadequate, and sided with the Huns. Attila defeated Karidach’s rival chieftains, installed him as the sole ruler of the Akatzirs, and invited him to visit his court. Karidach thanked him profusely for the invitation, and went on to say that “it would be too hard on a mortal man to look into the face of a god.

For, as one cannot stare into the sun’s disc, even less could

one look into the face of the greatest god without suffering

injury.” Attila must have been pleased, for he confirmed Karidach in

his rule. Priscus’s chronicle confirms that the Khazars appeared on

the European scene about the middle of the fifth century as a people

under Hunnish sovereignty, and may be regarded, together with the

Magyars and other tribes, as a later offspring of Attila’s horde.

A number of these tribes — the Sabirs, Saragurs, Samandars, Balanjars, etc. — are from this date onward no longer mentioned by name in the sources: they had been subdued or absorbed by the Khazars. The toughest resistance, apparently, was offered by the powerful Bulgars. But they too were crushingly defeated (circa 641), and as a result the nation split into two: some of them migrated westward to the Danube, into the region of modern Bulgaria, others north-eastward to the middle Volga, the latter remaining under Khazar suzerainty. We shall frequently encounter both Danube Bulgars and Volga Bulgars in the course of this narrative. But before becoming a sovereign state, the Khazars still had to serve their apprenticeship under another short-lived power, the so-called West Turkish Empire, or Turkut kingdom.

It was a confederation of tribes, held together by a ruler: the Kagan or Khagan — a title which the Khazar rulers too were subsequently to adopt. This first Turkish state — if one may call it that — lasted for a century (circa 550-650) and then fell apart, leaving hardly any trace. However, it was only after the establishment of this kingdom that the name “Turk” was used to apply to a specific nation, as distinct from other Turkic-speaking peoples like the Khazars and Bulgars. The Khazars had been under Hun tutelage, then under Turkish tutelage. After the eclipse of the Turks in the middle of the seventh century it was their turn to rule the “Kingdom of the North”, as the Persians and Byzantines came to call it.

According to one tradition, the great Persian King Khusraw

(Chosroes) Anushirwan (the Blessed) had three golden guest-thrones

in his palace, reserved for the Emperors of Byzantium, China and of

the Khazars. No state visits from these potentates materialized, and

the golden thrones — if they existed — must have served a purely

symbolic purpose. But whether fact or legend, the story fits in well

with Emperor Constantine’s official account of the triple gold seal

assigned by the Imperial Chancery to the ruler of the Khazars.

There are several versions of the role played by the Khazars in that campaign which seems to have been somewhat inglorious — but the principal facts are well established. The Khazars provided Heraclius with 40000 horsemen under a chieftain named Ziebel, who participated in the advance into Persia, but then — presumably fed up with the cautious strategy of the Greeks — turned back to lay siege on Tiflis; this was unsuccessful, but the next year they again joined forces with Heraclius, took the Georgian capital, and returned with rich plunder. Gibbon has given a colourful description (based on Theophanes) of the first meeting between the Roman Emperor and the Khazar chieftain.

Eudocia (or Epiphania) was the only daughter of Heraclius by his first wife. The promise to give her in marriage to the “Turk” indicates once more the high value set by the Byzantine Court on the Khazar alliance. However, the marriage came to naught because Ziebel died while Eudocia and her suite were on their way to him. There is also an ambivalent reference in Theophanes to the effect that Ziebel “presented his son, a beardless boy” to the Emperor — as a quid pro quo?

There is another picturesque passage in an Armenian chronicle,

quoting the text of what might be called an Order of Mobilization

issued by the Khazar ruler for the second campaign against Persia:

it was addressed to “all tribes and peoples [under Khazar

authority], inhabitants of the mountains and the plains, living

under roofs or the open sky, having their heads shaved or wearing

their hair long”. This gives us a first intimation of the

heterogeneous ethnic mosaic that was to compose the Khazar Empire.

The “real Khazars” who ruled it were probably always a minority — as

the Austrians were in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

It fell to the latter to bear the brunt of the Arab attack in its initial stages, and to protect the plains of Eastern Europe from the invaders. In the first twenty years of the Hegira — Mohammed’s flight to Medina in 622, with which the Arab calendar starts — the Muslims had conquered Persia, Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and surrounded the Byzantine heartland (the present-day Turkey) in a deadly semi-circle, which extended from the Mediterranean to the Caucasus and the southern shores of the Caspian. The Caucasus was a formidable natural obstacle, but no more forbidding than the Pyrenees; and it could be negotiated by the pass of Dariel or bypassed through the defile of Darband, along the Caspian shore.

This fortified defile, called by the Arabs Bab al Abwab, the Gate of Gates, was a kind of historic turnstile through which the Khazars and other marauding tribes had from time immemorial attacked the countries of the south and retreated again. Now it was the turn of the Arabs. Between 642 and 652 they repeatedly broke through the Darband Gate and advanced deep into Khazaria, attempting to capture Balanjar, the nearest town, and thus secure a foothold on the European side of the Caucasus. They were beaten back on every occasion in this first phase of the Arab-Khazar war; the last time in 652, in a great battle in which both sides used artillery (catapults and ballistae).

Four thousand Arabs were killed, including their commander, Abdal-Rahman ibn-Rabiah; the rest fled in disorder across the mountains. For the next thirty or forty years the Arabs did not attempt any further incursions into the Khazar stronghold. Their main attacks were now aimed at Byzantium. On several occasions they laid siege to Constantinople by land and by sea; had they been able to outflank the capital across the Caucasus and round the Black Sea, the fate of the Roman Empire would probably have been sealed. The Khazars, in the meantime, having subjugated the Bulgars and Magyars, completed their western expansion into the Ukraine and the Crimea.

But these were no longer haphazard raids to amass booty and prisoners; they were wars of conquest, incorporating the conquered people into an empire with a stable administration, ruled by the mighty Kagan, who appointed his provincial governors to administer and levy taxes in the conquered territories. At the beginning of the eighth century their state was sufficiently consolidated for the Khazars to take the offensive against the Arabs. From a distance of more than a thousand years, the period of intermittent warfare that followed (the so-called ‘second Arab war”, 722-37) looks like a series of tedious episodes on a local scale, following the same, repetitive pattern: the Khazar cavalry in their heavy armour breaking through the pass of Dariel or the Gate of Darband into the Caliph’s domains to the south; followed by Arab counter-thrusts through the same pass or the defile, towards the Volga and back again.

Looking thus through the wrong end of the telescope, one is reminded of the old jingle about the noble Duke of York who had ten thousand men; “he marched them up to the top of the hill. And he marched them down again.” In fact, the Arab sources (though they often exaggerate) speak of armies of 100000, even of 300000, men engaged on either side — probably outnumbering the armies which decided the fate of the Western world at the battle of Tours about the same time. The death-defying fanaticism which characterized these wars is illustrated by episodes such as the suicide by fire of a whole Khazar town as an alternative to surrender; the poisoning of the water supply of Bab al Abwab by an Arab general; or by the traditional exhortation which would halt the rout of a defeated Arab army and make it fight to the last man: “To the Garden, Muslims, not the Fire” — the joys of Paradise being assured to every Muslim soldier killed in the Holy War.

At one stage during these fifteen years of fighting the Khazars overran Georgia and Armenia, inflicted a total defeat on the Arab army in the battle of Ardabil (AD 730) and advanced as far as Mosul and Dyarbakir, more than half-way to Damascus, capital of the Caliphate. But a freshly raised Muslim army stemmed the tide, and the Khazars retreated homewards across the mountains. The next year Maslamah ibn-Abd-al-Malik, most famed Arab general of his time, who had formerly commanded the siege of Constantinople, took Balanjar and even got as far as Samandar, another large Khazar town further north. But once more the invaders were unable to establish a permanent garrison, and once more they were forced to retreat across the Caucasus.

The sigh of relief experienced in the Roman Empire assumed a tangible form through another dynastic alliance, when the heir to the throne was married to a Khazar princess, whose son was to rule Byzantium as Leo the Khazar. The last Arab campaign was led by the future Caliph Marwan II, and ended in a Pyrrhic victory. Marwan made an offer of alliance to the Khazar Kagan, then attacked by surprise through both passes. The Khazar army, unable to recover from the initial shock, retreated as far as the Volga. The Kagan was forced to ask for terms; Marwan, in accordance with the routine followed in other conquered countries, requested the Kagan’s conversion to the True Faith.

The Kagan complied, but his conversion to Islam must have been an act of lip-service, for no more is heard of the episode in the Arab or Byzantine sources — in contrast to the lasting effects of the establishment of Judaism as the state religion which took place a few years later. Content with the results achieved, Marwan bid farewell to Khazaria and marched his army back to Transcaucasia — without leaving any garrison, governor or administrative apparatus behind. On the contrary, a short time later he requested terms for another alliance with the Khazars against the rebellious tribes of the south. It had been a narrow escape. The reasons which prompted Marwan’s apparent magnanimity are a matter of conjecture — as so much else in this bizarre chapter of history. Perhaps the Arabs realized that, unlike the relatively civilized Persians, Armenians or Georgians, these ferocious Barbarians of the North could not be ruled by a Muslim puppet prince and a small garrison.

Yet Marwan needed every man of his army to quell major rebellions in Syria and other parts of the Omayad Caliphate, which was in the process of breaking up. Marwan himself was the chief commander in the civil wars that followed, and became in 744 the last of the Omayad Caliphs (only to be assassinated six years later when the Caliphate passed to the Abbasid dynasty). Given this background, Marwan was simply not in a position to exhaust his resources by further wars with the Khazars. He had to content himself with teaching them a lesson which would deter them from further incursions across the Caucasus. Thus the gigantic Muslim pincer movement across the Pyrenees in the west and across the Caucasus into Eastern Europe was halted at both ends about the same time.

As Charles Martel’s Franks saved Gaul and Western Europe, so the Khazars saved the eastern approaches to the Volga, the Danube, and the East Roman Empire itself. On this point at least, the Soviet archaeologist and historian, Artamonov, and the American historian, Dunlop, are in full agreement. I have already quoted the latter to the effect that but for the Khazars, “Byzantium, the bulwark of European civilization to the East, would have found itself outflanked by the Arabs”, and that history might have taken a different course. Artamonov is of the same opinion:

Lastly, the Professor of Russian History in the University of

Oxford, Dimitry Obolensky: “The main contribution of the Khazars to

world history was their success in holding the line of the Caucasus

against the northward onslaught of the Arabs.” Marwan was not only

the last Arab general to attack the Khazars, he was also the last

Caliph to pursue an expansionist policy devoted, at least in theory,

to the ideal of making Islam triumph all over the world. With the

Abbasid caliphs the wars of conquest ceased, the revived influence

of the old Persian culture created a mellower climate, and

eventually gave rise to the splendours of Baghdad under Harun al

Rashid.

After ten years of intolerable misrule there was a revolution, and the new Emperor, Leontius, ordered Justinian’s mutilation and banishment:

During his exile in Cherson, Justinian kept plotting to regain his throne. After three years he saw his chances improving when, back in Byzantium, Leontius was de-throned and also had his nose cut off. Justinian escaped from Cherson into the Khazar-ruled town of Doros in the Crimea and had a meeting with the Kagan of the Khazars, King Busir or Bazir. The Kagan must have welcomed the opportunity of putting his fingers into the rich pie of Byzantine dynastic policies, for he formed an alliance with Justinian and gave him his sister in marriage.

This sister, who was baptized by the name of Theodora, and later duly crowned, seems to have been the only decent person in this series of sordid intrigues, and to bear genuine love for her noseless husband (who was still only in his early thirties). The couple and their band of followers were now moved to the town of Phanagoria (the present Taman) on the eastern shore of the strait of Kerch, which had a Khazar governor. Here they made preparations for the invasion of Byzantium with the aid of the Khazar armies which King Busir had apparently promised. But the envoys of the new Emperor, Tiberias III, persuaded Busir to change his mind, by offering him a rich reward in gold if he delivered Justinian, dead or alive, to the Byzantines.

King Busir accordingly gave orders to two of his henchmen, named Papatzes and Balgitres, to assassinate his brother-in-law. But faithful Theodora got wind of the plot and warned her husband. Justinian invited Papatzes and Balgitres separately to his quarters, and strangled each in turn with a cord. Then he took ship, sailed across the Black Sea into the Danube estuary, and made a new alliance with a powerful Bulgar tribe.

Their king, Terbolis, proved for the time being more reliable than the Khazar Kagan, for in 704 he provided Justinian with 15000 horsemen to attack Constantinople. The Byzantines had, after ten years, either forgotten the darker sides of Justinian’s former rule, or else found their present ruler even more intolerable, for they promptly rose against Tiberias and reinstated Justinian on the throne. The Bulgar King was rewarded with “a heap of gold coin which he measured with his Scythian whip” and went home (only to get involved in a new war against Byzantium a few years later).

Justinian’s second reign (704-711) proved even worse than the first; “he considered the axe, the cord and the rack as the only instruments of royalty”. He became mentally unbalanced, obsessed with hatred against the inhabitants of Cherson, where he had spent most of the bitter years of his exile, and sent an expedition against the town. Some of Cherson’s leading citizens were burnt alive, others drowned, and many prisoners taken, but this was not enough to assuage Justinian’s lust for revenge, for he sent a second expedition with orders to raze the city to the ground. However, this time his troops were halted by a mighty Khazar army; whereupon Justinian’s representative in the Crimea, a certain Bardanes, changed sides and joined the Khazars.

The demoralized Byzantine expeditionary force abjured its allegiance to Justinian and elected Bardanes as Emperor, under the name of Philippicus. But since Philippicus was in Khazar hands, the insurgents had to pay a heavy ransom to the Kagan to get their new Emperor back. When the expeditionary force returned to Constantinople, Justinian and his son were assassinated and Philippicus, greeted as a liberator, was installed on the throne only to be deposed and blinded a couple of years later. The point of this gory tale is to show the influence which the Khazars at this stage exercised over the destinies of the East Roman Empire — in addition to their role as defenders of the Caucasian bulwark against the Muslims.

Bardanes-Philippicus was an

emperor of the Khazars’ making, and the end of Justinian’s reign of

terror was brought about by his brother-in-law, the Kagan. To quote

Dunlop: “It does not seem an exaggeration to say that at this

juncture the Khaquan was able practically to give a new ruler to the

Greek empire.”

One is a letter, purportedly from a Khazar king, to be discussed in Chapter 2; the other is a travelogue by an observant Arab traveller, Ibn Fadlan, who — like Priscus — was a member of a diplomatic mission from a civilized court to the Barbarians of the North. The court was that of the Caliph al Muktadir, and the diplomatic mission travelled from Baghdad through Persia and Bukhara to the land of the Volga Bulgars. The official pretext for this grandiose expedition was a letter of invitation from the Bulgar king, who asked the Caliph (a) for religious instructors to convert his people to Islam, and (b) to build him a fortress which would enable him to defy his overlord, the King of the Khazars.

The invitation — which was no doubt prearranged by earlier diplomatic contacts — also provided an opportunity to create goodwill among the various Turkish tribes inhabiting territories through which the mission had to pass, by preaching the message of the Koran and distributing huge amounts of gold bakhshish. The opening paragraphs of our traveller’s account read:

The date of the expedition, it will he noted, is much later than the events described in the previous section. But as far as the customs and institutions of the Khazars’ pagan neighbours are concerned, this probably makes not much difference; and the glimpses we get of the life of these nomadic tribes convey at least some idea of what life among the Khazars may have been during that earlier period — before the conversion — when they adhered to a form of Shamanism similar to that still practised by their neighbours in Ibn Fadlan’s time.

The progress of the mission was slow and apparently uneventful until they reached Khwarizm, the border province of the Caliphate south of the Sea of Aral. Here the governor in charge of the province tried to stop them from proceeding further by arguing that between his country and the kingdom of the Bulgars there were “a thousand tribes of disbelievers” who were sure to kill them. In fact his attempts to disregard the Caliph’s instructions to let the mission pass might have been due to other motives: he realized that the mission was indirectly aimed against the Khazars, with whom he maintained a flourishing trade and friendly relations. In the end, however, he had to give in, and the mission was allowed to proceed to Gurganj on the estuary of the Amu-Darya. Here they hibernated for three months, because of the intense cold — a factor which looms large in many Arab travellers’ tales:

Around the middle of February the thaw set in. The mission arranged to join a mighty caravan of 5000 men and 3000 pack animals to cross the northern steppes, and bought the necessary supplies: camels, skin boats made of camel hides for crossing rivers, bread, millet and spiced meat for three months. The natives warned them about the even more frightful cold in the north, and advised them what clothes to wear:

Ibn Fadlan, the fastidious Arab, liked neither the climate nor the people of Khwarizm:

There are many such incidents, which Ibn Fadlan reports without appreciating the independence of mind which they reflect. Nor did the envoy of the Baghdad court appreciate the nomadic tribesmen’s fundamental contempt for authority. The following episode also occurred in the country of the powerful Ghuzz Turks, who paid tribute to the Khazars and, according to some sources, were closely related to them:

The democratic methods of the Ghuzz, practised when a decision had to be taken, were even more bewildering to the representative of an authoritarian theocracy:

The sexual mores of the Ghuzz — and other tribes — were a remarkable mixture of liberalism and savagery:

He does not say whether the same punishment was meted out to the guilty woman. Later on, when talking about the Volga Bulgars, he describes an equally savage method of splitting adulterers into two, applied to both men and women. Yet, he notes with astonishment, Bulgars of both sexes swim naked in their rivers, and have as little bodily shame as the Ghuzz. As for homosexuality — which in Arab countries was taken as a matter of course — Ibn Fadlan says that it is “regarded by the Turks as a terrible sin”.

But in the only episode he relates to prove his point, the seducer of a “beardless youth” gets away with a fine of 400 sheep. Accustomed to the splendid baths of Baghdad, our traveller could not get over the dirtiness of the Turks.

When the Ghuzz commander-in-chief took off his luxurious coat of brocade to don a new coat the mission had brought him, they saw that his underclothes were “fraying apart from dirt, for it is their custom never to take off the garment they wear close to their bodies until it disintegrates”. Another Turkish tribe, the Bashkirs, ‘shave their beards and eat their lice. They search the folds of their undergarments and crack the lice with their teeth.” When Ibn Fadlan watched a Bashkir do this, the latter remarked to him: “They are delicious.”

All in all, it is not an engaging picture. Our fastidious traveller’s contempt for the barbarians was profound. But it was only aroused by their uncleanliness and what he considered as indecent exposure of the body; the savagery of their punishments and sacrificial rites leave him quite indifferent. Thus he describes the Bulgars’ punishment for manslaughter with detached interest, without his otherwise frequent expressions of indignation:

Among the Volga Bulgars, Ibn Fadlan found a strange custom:

Commenting on this passage, the Turkish orientalist Zeki Validi Togan, undisputed authority on Ibn Fadlan and his times, has this to say:

This leads one to believe that the custom should be regarded as a measure of social defence against change, a punishment of non-conformists and potential innovators. But a few lines further down he gives a different interpretation:

Perhaps both types of motivation were mixed together: ‘since

sacrifice is a necessity, let’s sacrifice the trouble-makers”. We

shall see that human sacrifice was also practised by the Khazars —

including the ritual killing of the king at the end of his reign. We

may assume that many other similarities existed between the customs

of the tribes described by Ibn Fadlan and those of the Khazars.

Unfortunately he was debarred from visiting the Khazar capital and

had to rely on information collected in territories under Khazar

dominion, and particularly at the Bulgar court.

They argued among themselves for seven days, while Ibn Fadlan and his people feared the worst. In the end the Ghuzz let them go; we are not told why. Probably Ibn Fadlan succeeded in persuading them that his mission was in fact directed against the Khazars. The Ghuzz had earlier on fought with the Khazars against another Turkish tribe, the Pechenegs, but more recently had shown a hostile attitude; hence the hostages the Khazars took.

The Khazar menace loomed large on the horizon all along the journey. North of the Caspian they made another huge detour before reaching the Bulgar encampment somewhere near the confluence of the Volga and the Kama. There the King and leaders of the Bulgars were waiting for them in a state of acute anxiety. As soon as the ceremonies and festivities were over, the King sent for Ibn Fadlan to discuss business.

And apparently he had every reason to be afraid, as Ibn Fadlan relates:

It sounds like a refrain. Ibn Fadlan also specifies the annual

tribute the Bulgar King had to pay the Khazars: one sable fur from

each household in his realm. Since the number of Bulgar households

(i.e., tents) is estimated to have been around 50000, and since

Bulgar sable fur was highly valued all over the world, the tribute

was a handsome one.

Ibn Fadlan then proceeds to give a rather fanciful description of the Kagan’s harem, where each of the eighty-five wives and concubines has a “palace of her own”, and an attendant or eunuch who, at the King’s command, brings her to his alcove “faster than the blinking of an eye. After a few more dubious remarks about the “customs” of the Khazar Kagan (we shall return to them later), Ibn Fadlan at last provides some factual information about the country:

Ibn Fadlan’s travel report, as far as it is preserved, ends with the words:

I have quoted Ibn Fadlan’s odyssey at some length, not so much because of the scant information he provides about the Khazars themselves, but because of the light it throws on the world which surrounded them, the stark barbarity of the people amidst whom they lived, reflecting their own past, prior to the conversion. For, by the time of Ibn Fadlan’s visit to the Bulgars, Khazaria was a surprisingly modern country compared to its neighbours.

The contrast is evidenced by the reports of other Arab historians, and is present on every level, from housing to the administration of justice. The Bulgars still live exclusively in tents, including the King, although the royal tent is “very large, holding a thousand people or more”. On the other hand, the Khazar Kagan inhabits a castle built of burnt brick, his ladies are said to inhabit “palaces with roofs of teak”, and the Muslims have several mosques, among them “one whose minaret rises above the royal castle”. In the fertile regions, their farms and cultivated areas stretched out continuously over sixty or seventy miles. They also had extensive vineyards.

Thus Ibn Hawkal:

The region north of the Caucasus was extremely fertile. In AD 968 Ibn Hawkal met a man who had visited it after a Russian raid: “He said there is not a pittance left for the poor in any vineyard or garden, not a leaf on the bough.… [But] owing to the excellence of their land and the abundance of its produce it will not take three years until it becomes again what it was.” Caucasian wine is still a delight, consumed in vast quantities in the Soviet Union.

However, the royal treasuries’ main source of income was foreign trade. The sheer volume of the trading caravans plying their way between Central Asia and the Volga-Ural region is indicated by Ibn Fadlan: we remember that the caravan his mission joined at Gurganj consisted of “5000 men and 3000 pack animals”. Making due allowance for exaggeration, it must still have been a mighty caravan, and we do not know how many of these were at any time on the move. Nor what goods they transported — although textiles, dried fruit, honey, wax and spices seem to have played an important part. A second major trade route led across the Caucasus to Armenia, Georgia, Persia and Byzantium.

A third consisted of the increasing traffic of Rus merchant fleets down the Volga to the eastern shores of the Khazar Sea, carrying mainly precious furs much in demand among the Muslim aristocracy, and slaves from the north, sold at the slave market of Itil. On all these transit goods, including the slaves, the Khazar ruler levied a tax of ten per cent. Adding to this the tribute paid by Bulgars, Magyars, Burtas and so on, one realizes that Khazaria was a prosperous country — but also that its prosperity depended to a large extent on its military power, and the prestige it conveyed on its tax collectors and customs officials.

Apart from the fertile regions of the south, with their vineyards and orchards, the country was poor in natural resources. One Arab historian (Istakhri) says that the only native product they exported was isinglass. This again is certainly an exaggeration, yet the fact remains that their main commercial activity seems to have consisted in re-exporting goods brought in from abroad. Among these goods, honey and candle-wax particularly caught the Arab chroniclers’ imagination. Thus Muqaddasi:

It is true that one source — the Darband Namah — mentions gold or silver mines in Khazar territory, but their location has not been ascertained. On the other hand, several of the sources mention Khazar merchandise seen in Baghdad, and the presence of Khazar merchants in Constantinople, Alexandria and as far afield as Samara and Fergana. Thus Khazaria was by no means isolated from the civilized world; compared to its tribal neighbours in the north it was a cosmopolitan country, open to all sorts of cultural and religious influences, yet jealously defending its independence against the two ecclesiastical world powers.

We shall see that this attitude prepared the ground for the coup de théâtre — or coup d”état — which established Judaism as the state religion. The arts and crafts seem to have flourished, including haute couture. When the future Emperor Constantine V married the Khazar Kagan’s daughter (see above, section 1), she brought with her dowry a splendid dress which so impressed the Byzantine court that it was adopted as a male ceremonial robe; they called it tzitzakion, derived from the Khazar-Turkish pet-name of the Princess, which was Chichak or “flower” (until she was baptized Eirene).

“Here,” Toynbee comments, “we have an

illuminating fragment of cultural history.” When another Khazar

princess married the Muslim governor of Armenia, her cavalcade

contained, apart from attendants and slaves, ten tents mounted on

wheels, “made of the finest silk, with gold- and silver-plated

doors, the floors covered with sable furs. Twenty others carried the

gold and silver vessels and other treasures which were her dowry”.

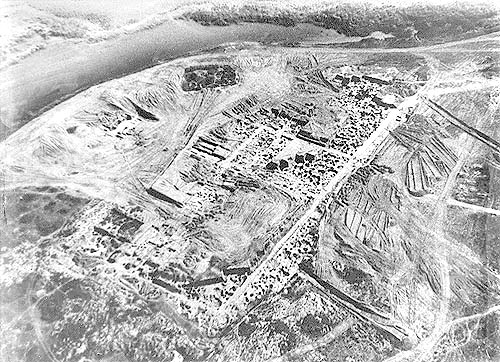

The Kagan himself travelled in a mobile tent even more luxuriously

equipped, carrying on its top a pomegranate of gold. Khazar fortress at Sarkel (Belaya Vyezha, Russia). Aerial photo from excavations conducted by M. I. Artamanov during the 1930's.

After his exhaustive survey of the archaeological and documentary evidence (mostly from Soviet sources), Bartha concludes:

The last remark of the Hungarian scholar refers to the spectacular archaeological finds known as the “Treasure of Nagyszentmiklos” (see frontispiece). The treasure, consisting of twentythree gold vessels, dating from the tenth century, was found in 1791 in the vicinity of the village of that name. Bartha points out that the figure of the “victorious Prince” dragging a prisoner along by his hair, and the mythological scene at the back of the golden jar, as well as the design of other ornamental objects, show close affinities with the finds in Novi Pazar in Bulgaria and in Khazar Sarkel.

As both

Magyars and Bulgars were under Khazar suzerainty for protracted

periods, this is not very surprising, and the warrior, together with

the rest of the treasure, gives us at least some idea of the arts

practised within the Khazar Empire (the Persian and Byzantine

influence is predominant, as one would expect). One school of

Hungarian archaeologists maintains that the tenth century gold- and

silversmiths working in Hungary were actually Khazars. As we shall

see later on (see III, 7, 8), when the Magyars migrated to Hungary

in 896 they were led by a dissident Khazar tribe, known as the

Kabars, who settled with them in their new home. The Kabar-Khazars

were known as skilled gold and silversmiths; the (originally more

primitive) Magyars only acquired these skills in their new country.

Thus the theory of the Khazar origin of at least some of the

archaeological finds in Hungary is not implausible — as will become

clearer in the light of the Magyar-Khazar nexus discussed later on.

And Ibn Hawkal:

Here we have another important clue to the Khazar dominance: a permanent professional army, with a Praetorian Guard which, in peacetime, effectively controlled the ethnic patchwork, and in times of war served as a hard core for the armed horde, which, as we have seen, may have swollen at times to a hundred thousand or more.

The capital of this motley empire was at first probably the fortress of Balanjar in the northern foothills of the Caucasus; after the Arab raids in the eighth century it was transferred to Samandar, on the western shore of the Caspian; and lastly to Itil in the estuary of the Volga. We have several descriptions of Itil, which are fairly consistent with each other. It was a twin city, built on both sides of the river. The eastern half was called Khazaran, the western half Itil; the two were connected by a pontoon bridge. The western half was surrounded by a fortified wall, built of brick; it contained the palaces and courts of the Kagan and the Bek, the habitations of their attendants and of the “pure-bred Khazars”.

The wall had four gates, one of them facing the river. Across the river, on the east bank, lived “the Muslims and idol worshippers”; this part also housed the mosques, markets, baths and other public amenities. Several Arab writers were impressed by the number of mosques in the Muslim quarter and the height of the principal minaret. They also kept stressing the autonomy enjoyed by the Muslim courts and clergy. Here is what al-Masudi, known as “the Herodotus among the Arabs”, has to say on this subject in his oft-quoted work Meadows of Gold Mines and Precious Stones:

In reading these lines by the foremost Arab historian, written in the first half of the tenth century, one is tempted to take a perhaps too idyllic view of life in the Khazar kingdom. Thus we read in the article “Khazars” in the Jewish Encyclopaedia: “In a time when fanaticism, ignorance and anarchy reigned in Western Europe, the Kingdom of the Khazars could boast of its just and broad-minded administration.” This, as we have seen, is partly true; but only partly. There is no evidence of the Khazars engaging in religious persecution, either before or after the conversion to Judaism.

In this respect they may be called more tolerant and enlightened than the East Roman Empire, or Islam in its early stages. On the other hand, they seem to have preserved some barbaric rituals from their tribal past. We have heard Ibn Fadlan on the killings of the royal gravediggers. He also has something to say about another archaic custom regicide: “The period of the king’s rule is forty years. If he exceeds this time by a single day, his subjects and attendants kill him, saying “His reasoning is already dimmed, and his insight confused”.” Istakhri has a different version of it:

Bury is doubtful whether to believe this kind of Arab traveller’s lore, and one would indeed be inclined to dismiss it, if ritual regicide had not been such a widespread phenomenon among primitive (and not-so-primitive) people. Frazer laid great emphasis on the connection between the concept of the King’s divinity, and the sacred obligation to kill him after a fixed period, or when his vitality is on the wane, so that the divine power may find a more youthful and vigorous incarnation. It speaks in Istakhri’s favour that the bizarre ceremony of “choking” the future King has been reported in existence apparently not so long ago among another people, the Kok-Turks.

Zeki Validi quotes a French anthropologist, St Julien, writing in 1864:

We do not know whether the Khazar rite of slaying the King (if it ever existed) fell into abeyance when they adopted Judaism, in which case the Arab writers were confusing past with present practices as they did all the time, compiling earlier travellers’ reports, and attributing them to contemporaries. However that may be, the point to be retained, and which seems beyond dispute, is the divine role attributed to the Kagan, regardless whether or not it implied his ultimate sacrifice. We have heard before that he was venerated, but virtually kept in seclusion, cut off from the people, until he was buried with enormous ceremony.

The affairs of state, including leadership of the army, were managed by the Bek (sometimes also called the Kagan Bek), who wielded all effective power. On this point Arab sources and modern historians are in agreement, and the latter usually describe the Khazar system of government as a “double kingship”, the Kagan representing divine, the Bek secular, power. The Khazar double kingship has been compared — quite mistakenly, it Seems — with the Spartan dyarchy and with the superficially similar dual leadership among various Turkish tribes. However, the two kings of Sparta, descendants of two leading families, wielded equal power; and as for the dual leadership among nomadic tribes, there is no evidence of a basic division of functions as among the Khazars.

A more valid comparison is the system of government in Japan, from the Middle Ages to 1867, where secular power was concentrated in the hands of the shogun, while the Mikado was worshipped from afar as a divine figurehead. Cassel has suggested an attractive analogy between the Khazar system of government and the game of chess. The double kingship is represented on the chess-board by the King (the Kagan) and the Queen (the Bek). The King is kept in seclusion, protected by his attendants, has little power and can only move one short step at a time.

The Queen, by contrast, is the most powerful presence on the board, which she dominates. Yet the Queen may be lost and the game still continued, whereas the fall of the King is the ultimate disaster which instantly brings the contest to an end. The double kingship thus seems to indicate a categorical distinction between the sacred and the profane in the mentality of the Khazars. The divine attributes of the Kagan are much in evidence in the following passage from Ibn Hawkal:

The passage about the virtuous young man selling bread, or whatever it is, in the bazaar sounds rather like a tale about Harun al Rashid. If he was heir to the golden throne reserved for Jews, why then was he brought up as a poor Muslim? If we are to make any sense at all of the story, we must assume that the Kagan was chosen on the strength of his noble virtues, but chosen among members of the “Imperial Race” or “family of notables”.

This is in fact the view of Artamonov and Zeki Validi. Artamonov holds that the Khazars and other Turkish people were ruled by descendants of the Turkut dynasty, the erstwhile sovereigns of the defunct Turk Empire (cf. above, section 3). Zeki Validi suggests that the “Imperial Race” or “family of notables”, to which the Kagan must belong, refers to the ancient dynasty of the Asena, mentioned in Chinese sources, a kind of desert aristocracy, from which Turkish and Mongol rulers traditionally claimed descent. This sounds fairly plausible and goes some way towards reconciling the contradictory values implied in the narrative just quoted: the noble youth without a dirhem to his name — and the pomp and circumstance surrounding the golden throne. We are witnessing the overlap of two traditions, like the optical interference of two wave-patterns on a screen: the asceticism of a tribe of hard-living desert nomads, and the glitter of a royal court prospering on its commerce and crafts, and striving to outshine its rivals in Baghdad and Constantinople.

After all, the creeds professed by those sumptuous courts had also been inspired by ascetic desert-prophets in the past. All this does not explain the startling division of divine and secular power, apparently unique in that period and region. As Bury wrote:

A speculative answer to this question has recently been proposed by Artamonov. He suggests that the acceptance of Judaism as the state religion was the result of a coup d'état, which at the same time reduced the Kagan, descendant of a pagan dynasty whose allegiance to Mosaic law could not really be trusted, to a mere figurehead. This is a hypothesis as good as any other — and with as little evidence to support it. Yet it seems probable that the two events — the adoption of Judaism and the establishment of the double kingship — were somehow connected.

|