"The traditional history denies,

however, that the uranium on board U-234 was enriched and therefore

easily usable in an atomic bomb. The accepted theory asserts there

is no evidence that the uranium stocks of U-234 were transferred

into the Manhattan Project... And the traditional history asserts

that the bomb components on board (the) U-234 arrived too late to

be included in the atomic bombs that were dropped on Japan.

"The documentation indicates

quite differently on all accounts. "

Carter P. Hydrick

Critical Mass:

The Real Story of the Atomic Bomb and the Birth of the Nuclear Age.'

1

In December of 1944, an unhappy report is made to

some unhappy people:

"A study of the shipment of (bomb grade

uranium) for the past three months shows the following....: At present

rate we will have 10 kilos about February 7 and 15 kilos about May

1."2

This was bad news indeed, for a uranium

based atom bomb required between 10-100 kilograms by the earliest

estimates (ca. 1942), and, by the time this memo was written, about

50 kilos, the more accurate calculation of critical mass needed to

make an atom bomb from uranium.

One may imagine the consternation this memo must

have caused at headquarters. The was, perhaps, a considerable degree

of yelling and screaming and finger pointing and other histrionics,

interlarded with desperate orders to re-double efforts amid the fire-

tinged skies of the war's Wagnerian Gotterdammerung.

1 Carter

Hydrick, Critical Mass: the Real Story of the Atomic Bomb and the

Birth of the Nuclear Age, Internet published manuscript,

http://saba.fateback.com/criticalmass/begin.html,

1998, p. 6.

2 Ibid., p. 11.

The problem, however, is that the memo is not German

at all. It originates within the Manhattan Project on December 28,

1944, from Eric Jette, the chief metallurgist at Los Alamos. One may

imagine the desperation it must have triggered, however, since the

Manhattan Project had consumed two billion dollars all in the pursuit

of plutonium and uranium atom bombs. By this time it was of course

apparent that there were significant and seemingly insurmountable

problems in designing a plutonium bomb, for the fuses available to

the Allies were simply far too slow to achieve the uniform compression

of a plutonium core within the very short span of time needed to initiate

uncontrolled nuclear fission.

That left the uranium bomb as the more immediately

feasible alternative - as the Germans had discovered years earlier

- to the acquisition of a functioning weapon within the projected

span of the war. Yet, after a veritable hemorrhage of dollars in pursuit

of the latter objective, the Manhattan Project was far short of the

necessary critical mass for a uranium bomb. And with the inevitability

of an invasion of Japan looming, the pressure on General Leslie Groves

to produce results was immense.

The lack of a sufficient stockpile, after years of

concentrated all-out effort, was in part explainable, for two years

earlier Fermi had been successful in construction of the first functioning

atomic reactor. That success had spurred the American project to commit

more seriously to the pursuit of a plutonium bomb. Accordingly, some

of the precious and scarce refined and enriched uranium 235 coming

out of Oak Ridge and Lawrence's beta calutrons was being siphoned

off as feedstock for enrichment and transmutation into plutonium in

the breeder reactors constructed at Handford, Washington for the purpose.

Thus, some of the fissionable uranium stockpile had been deliberately

diverted for plutonium production.3 The decision

was a logical one and the Manhattan Project decision- makers cannot

be faulted to taking it. The reason is simple. Pound for weapons grade

pound, a pound of plutonium will produce more bombs than a pound of

uranium. It thus made economic sense to convert enriched uranium to

plutonium, for more bombs would be possible with the same amount of

material.

3 Hydrick, op. cit, p. 12.

But in December of 1944, having pursued

both options, General Leslie Groves now stood on the verge of losing

both gambles. And let us not forget what had just happened in Europe to sour the

mood of "those in the know" in the United States even further.

There, six months after the Allied landings in Normandy and the headlong

dash across France, Allied armies had stalled on the borders of the

Reich. Allied intelligence analysts confidently reassured the generals

that no further significant German military offensive was possible,

and their optimism was reflected in the general mood of the citizenry

in France, Britain, and the United States.

The mood was brutally shattered

when, on December 16, 1944, the German Army and Luftwaffe mounted

one last, desperate offensive with secretly husbanded reserves in

the Ardennes forest, scene of their 1940 triumph against France. Within

a matter of hours, the offensive had broken through American lines,

surrounded, captured, or otherwise decimated the entire 116th American

infantry division, and days later, surrounded the 101st Airborne division

at Bastogne, and appeared well on the way to crossing the Meuse River

at Namur. On December 28, 1944, when the memo was written, the German

offensive had been stalled, but not stopped.

For the Allied officers privy to intelligence reports

and "in the loop" on the Manhattan Project, the offensive

was possibly seen as confirmation of their worst fears: the Germans

were close to a bomb, and were trying to buy time. The horrible thought

in the back of every Allied scientist's and engineer's head must have

been that after all the Allied military successes of the previous

years, the race for the bomb could still be won by the Germans.

And

if they were able to produce enough of them to put unbearable pressure

on any one of the Western Allies, the outcome of the war itself was

still in doubt. If, for example, the Germans had a-bombed British

and French cities, it is unlikely that a continuance of the would

have been politically feasible for Churchill's wartime coalition government.

In all likelihood it would have collapsed. A similar result would

have likely occurred in France. And without British and French bases

available for supply and forward deployment, the American military situation on the continent would

have become untenable, if not disastrous.

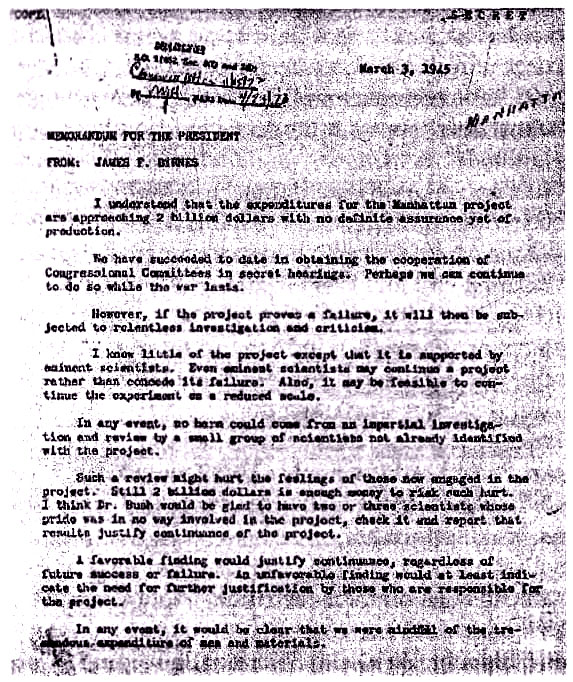

In any case, word of the Manhattan Project's difficulties

apparently leaked in the Washington DC political community, for United

States Senator James F. Byrnes got in on the act, writing a memorandum

to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and confirming that the Manhattan

Project was perceived - at least by some in the know - as being in

danger of failure:

SECRET March 3, 1945

MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT

FROM: JAMES F. BYRNES

I understand that the expenditures for the Manhattan

project are approaching 2 billion dollars with no definite assurance

yet of production.

We have succeeded to date in obtaining the cooperation

of Congressional Committees in secret meetings. Perhaps

we can continue to do so while the war lasts.

However, if the project proves a failure, it will

be subjected to relentless criticism.4

4 Memorandum of US Senator James F.

Byrnes to President Frankliin D. Roosevelt, March 3, 1945, cited in

Harald Fath, Geheime Kommandosache -S III Jonastal und die Siegeswaffenproduktion:

Weitere spurensuche nach Thuringens Manhattan Project (Schleusingen:

Amun Verlag, 2000), p. 41.

Senator Brynes' memorandum highlights the real problem

in the Manhattan Project, and the real, though certainly not publicly

known, military situation of the Allies ca. late 1944 and early 1945:

that in spite of tremendous conventional military success against

the Third Reich, the Western Allies and Soviet Russia could conceivably

still be forced to a "draw" if Germany deployed and used

atom bombs in sufficient numbers to affect the political situation

of the Western Allies.

Senator Byrnes' March

1945 Memorandum to President Roosevelt

With its stockpile of enriched uranium

already depleted by the decision to develop more plutonium for a

bomb (which as it turned out was undetonatable with existing British and American fuse technology

anyway) and far below that needed for a uranium-based atom bomb, "the

entire enterprise appeared destined for defeat."5

Not only defeat, but for "those in the know" in late 1944

and early 1945, the possibility was one of ignominious defeat and

horrible carnage.

5 Hydrick, op. cit, p. 13.

If the stocks of weapons grade uranium ca. late 1944

- early 1945 were about half of what they needed to be after two years

of research and production, and if this in turn was the cause of Senator

Byrnes' concern,

-

How then did the Manhattan Project acquire the large

remaining amount or uranium 235 needed in the few months from March

to the dropping of the Little Boy bomb on Hiroshima in August, only

five months away?

-

How did it accomplish this feat, if in feet after

some three years of production it had only produced less than half

of the needed supply of critical mass weapons grade uranium?

-

Where

did its missing uranium 235 come from?

-

And how did it solve the pressing

problem of the fuses for a plutonium bomb?

Of course the answer if that if the Manhattan Project

was incapable of producing enough enriched uranium in that short amount

of time - months rather than years - then its stocks had to have been

supplemented from external sources, and there is only one viable place

with the necessary technology to enrich uranium on that scale, as

seen in the previous chapter. That source was Nazi Germany. But the

Manhattan Project is not the only atom bomb project with some missing

uranium.

Germany too appears to have suffered the "missing

uranium syndrome" in the final days prior to and immediately

after the end of the war. But the problem in Germany's case is that

the missing uranium it not a few tens of kilos, but several hundred

tons. At this juncture, it is worth citing Carter Hydrick's excellent

research at length, in order to exhibit the full ramifications of

this problem:

From June of 1940 to the end of the war, Germany

seized 3,500 tons of uranium compounds from Belgium - almost three

times the amount Groves had purchased.... and stored it in salt mines

in Strassfurt, Germany. Groves brags that on 17 April, 1945, as the

war was winding down, Alsos recovered some 1,100 tons of uranium ore

from Strassfurt and an additional 31 tons in Toulouse, France .....

And he claims that the amount recovered was all that Germany had ever

held, asserting, therefore, that Germany had never had enough raw

material to process the uranium either for a plutonium reactor

pile or through magnetic separation techniques.

Obviously, if Strassfurt once held 3,500 tons and

only 1,130 were recovered, some 2,370 tons of uranium ore was unaccounted

for - still twice the amount the Manhattan Project possessed and is

assumed to have used throughout its entire wartime effort.... The

material has not been accounted for to this day....

As early as the summer of 1941, according to historian

Margaret Gowing, Germany had already refined 600 tons of uranium to

its oxide form, the form required for ionizing the material into a

gas, in which form the uranium isotopes could then be magnetically

or thermally separated or the oxide could be reduced to a metal for

a reactor pile. In fact, Professor Dr. Riehl, who was responsible

for all uranium throughout Germany during the course of the war, says

the figure was actually much higher....

To create either a uranium or plutonium bomb, at

some point uranium must be reduced to metal. In the case of plutonium,

U238 is metallized; for a uranium bomb, U235

is metallized. Because of uranium's difficult characteristics, however,

this metallurgical process is a tricky one. The United States struggled

with the problem early and still was not successful reducing uranium

to its metallic form in large production quantities until late in

1942. The German technicians, however,... by the end of 1940, had

already processed 280.6 kilograms into metal, over a quarter of a

ton.6

6 Hydrick, op. cit., p. 23, emphasis

added.

These observations require some additional commentary.

First, it is to be noted that Nazi Germany, by the

best available evidence, was missing approximately two thousand tons

of unrefined uranium ore by the war's end. Where did this ore go?

Second, it is clear that Nazi Germany was enriching

uranium on a massive scale, having refined

600 tons to oxide form for potential metallization

as early as 1940. This would require a large and dedicated

effort, with thousands of technicians, and a commensurately

large facility or facilities to accomplish the enrichment.

The figures, in other words, tend to corroborate the hypothesis

outlined in the previous chapter that the I.G. Farben "Buna"

factory at Auschwitz was not a Buna factory at all, but a huge

uranium enrichment facility. However, the date would imply another such facility, located elsewhere, since

the Auschwitz facility did not really begin production until sometime

in 1942.

Finally, it also seems clear that the Germans possessed

an enormous stock of metallic uranium. But what was the isotope? Was

it U238 for further enrichment and separation

into U235, was it intended perhaps as feedstock

for a reactor to be transmuted into plutonium, or was it already U235,

the necessary material for a uranium atom bomb? Given the statements

of the Japanese military attaché in Stockholm cited at the end of

the previous chapter - that the Germans may have used an atomic or

some other weapon of mass destruction on the Eastern Front ca. 1942-43,

and given Zinsser's affidavit cited in the first chapter of an atom

bomb test in October of 1944, it cannot be conclusively denied that

some of this enormous stockpile may also have been U235,

the essential component for a bomb.

In any case, these figures strongly suggest that

the Germans, ca. 1940-1942 were significantly ahead of the Allies

in one very important aspect of atom bomb production: the enrichment

of uranium, and therefore, this suggests also that they were demonstrably

ahead in the race for an actual functioning atom bomb during this

period. But the figures also raise another disturbing question: where

did this uranium go?

One answer lies in the mysterious case of a

U-boat,

the U-234, captured by the Americans in 1945.

The case of the U-234 is well-known in literature

about the Nazi atom bomb, and of course the Allied Legend is that

none of the material on board the U-boat found its way into the American

atom bomb project.

None of this could be further from the truth.

The U-234 was a very large mine-laying U-boat that

had been adapted as an undersea freighter to carry large cargoes.

Consider then the following "cargo manifest" of the U-234's

very odd cargo:

-

(1)

Two Japanese officers 7

-

(2)

80 gold-lined cylinders containing 560 kilograms of uranium

oxide 8

-

(3)

Several wooden cases or barrels full of "water"

-

(4) Infrared proximity fuses

(5) Dr. Heinz Schlicke, inventor of the fuses

When the U-234 was being loaded with its cargo in

Germany for the outward voyage, its radio operator, Wolfgang Hirschfeld,

observed the two Japanese officers writing "U235"

on the paper wrapping of the cylinders prior to their being loaded

into the submarine.9 Needless to say, this observation has called

forth the full range of debunking techniques normally applied by skeptics

to UFO sightings: low sun angles, poor lighting, distance was to great to see clearly, etc. etc. This is no surprise,

for if Hirschfeld saw what he saw, then the enormous implications

were obvious.

The use of gold lined cylinders is explainable by

the fact that uranium, a highly corrosive metal, is easily contaminated

if it comes into contact with other unstable elements. Gold, whose

radioactive shielding properties are as great as lead, is also, unlike

lead, a highly pure and stable element, and is therefore the element

of choice when storing or shipping highly enriched and pure uranium

for long periods of time, such as a voyage.10

Thus, the uranium oxide on board the U-234 was highly enriched uranium,

and most likely, highly enriched U235, the last

stage, perhaps, before being reduced to weapons grade or to

metallization

for a bomb (if it was already in weapons grade purity).

7

The two officers were Air Force Colonel Genzo Shosi,

an engineer, and Navy Captain Hideo Tomonaga. When the captain of

the U-234 made known his intentions to surrender the submarine, which

was then en route to Japan after the German surrender, the two Japanese

officers committed hari-kiri, and were buried at sea with full military

honors by the Germans.

8 Hydrick's comment on the U-234's

cargo manifest explains why the U- 234 was off limits to the American

press following its surrender: "Whoever first read the entry

and understood the frightening capabilities and potential purpose

of uranium must have been stunned by the entry." (op. cit, p.

7)

9 Hydrick, op. cit., p. 5.

10 Ibid., p. 8.

Indeed, if the Japanese officers'

labels on the cylinders were accurate, it is likely that it

was at the final stage of purity before metallization.

The cargo of the U-234 was so sensitive, in fact,

that when the U.S. Navy prepared its own cargo

manifest for the German submarine on June 16, 1945, the uranium oxide

had entirely disappeared from the list.11 Significantly,

within a week of the appearance of the U.S. Navy's version of the

U-234's cargo manifest, Oak Ridge's output of enriched uranium very

nearly doubled.12 This in itself is highly suspect,

since as late as March of 1945, as we have already seen, a U.S. Senator

is worried about the failure of the Manhattan Project, so much so

that he writes President Roosevelt a memorandum on the subject, and

of course, we have also already seen that the chief metallurgist of

Los Alamos laboratory indicates the stock of fissile U235

is far short of the needed critical mass, and would remain so for

several months.

11 Hydride, op. cit., p. 9.

12 Ibid., p. 11

The conclusion is therefore simple, but frightening:

the missing uranium used in the Manhattan Project was German, and

that means that Nazi Germany's atom bomb project was much further

along that the post-war Allied Legen would have us believe.

But what of the other two items in the U-234's strange

cargo manifest, the fuses and their inventor, Dr. Heinz Schilcke?

We have already noted that by late 1944 and early 1945, the American

plutonium bomb project had run afoul of some nasty mathematics: the

critical mass of a plutonium bomb, "imploded" or compressed

by surrounding conventional explosives, would have to be assembled

within 1/3000th of a second, otherwise the bomb would fail, and only

produce a kind of "atomic fizzling firecracker", a "radiological"

bomb producing very little explosion but a great deal of deadly radiation.

This was a speed far in excess of the capabilities of conventional

wire cabling and the ordinary fuses available to the Allied engineers.

It is known that late in the timetable of events

leading to the Trinity test of the plutonium bomb in New Mexico that

a design modification was introduced to the implosion device that

incorporated "radiation venting channels", allowing radiation

from the plutonium core to escape and reflect off the

surrounding reflectors as the detonator was fired, within billionths

of a second after the beginning of compression. There is no possible

way to explain this modification other than by the incorporation of

Dr. Schlicke's infrared proximity fuses into the final design of the

American bomb, since they enabled the fuses to react and fire are

the speed of light.13

In support of this historical reconstruction, there is a communication

from May 25, 1945 from the chief of Naval Operations,

to Portsmouth where the U-234 was brought after its surrender,

indicating that Dr. Schlicke, now a prisoner of war, would

be accompanied by three naval officers, to secure the fuses and

bring them to Washington.14 There Dr.

Schlicke

was apparently to give a lecture on the fuses

under the auspices of a "Mr. Alvarez,"15

who would appear to be none other than well-known

Manhattan Project scientist Dr. Luis Alvarez, the very man who,

according to the Allied Legend, "solved" the fusing problem for

the plutonium bomb!16

13 Q.v. Hydrick, op. cit, pp. 46-51, for a detailed discussion

of this issue and the historical problems it poses for the Allied

Legend.

14 Ibid., p. 46.

15 Ibid.

16 As I observed in my previous book, The Giza Death Star Deployed,

Dr.Luis Alvarez also had some other strange distinctions to his credit,

being one of the scientists allegedly involved with the alleged Roswell

"UFO" crash, the CIA's subsequent "Robertson Panel"

in the 1950s on UFOs and government policy, and subsequent cosmic ray

experiments inside the 2nd Pyramid at Giza.

So

it would appear that the surrender of the U-234 to the Americans

in 1945 solved the Manhattan Project's two biggest outstanding

problems: lack of sufficient supplies of weapons grade uranium,

and lack of adequate fusing technology to make a plutonium

bomb work. And this means that in the final analysis the Allied

Legend about the Germans having been "far behind" the Allies

in the race for the atom bomb is simply a incorrect in the extreme

in the best case, or a deliberate lie in the worst. But the fuses

raise another frightening specter: What were the Germansdeveloping

such highly sophisticated fuses for? Infrared heat-seeking

rockets, which they had developed, would be one answer, and of course an implosion device to compress critical

mass would be another.

But what about the other missing German uranium

mentioned previously? The mission of the U-234 and its precious cargo

thus raises certain other questions, and highlights other possibilities

in this regard. It is a fact that throughout the war Germany and Japan

both conducted long-range exchanges of officers and technology via

aircraft and submarine - the exchange of technology being mostly a

one-sided affair from Germany to Japan. It is conceivable that many

of these voyages - just as with the U-234 - would have included similar

transfers of uranium stocks and high technology to Japan. Some of

the missing uranium must therefore surely be looked for in the Far

East, in the Japanese atom bomb program.17

Similarly, during the war both Germany and Italy

undertook long-range flights to Japan, the Germans using their special

long- range heavy lift transport aircraft such as the Ju-290 for polar

flights. It is conceivable that these flights and their Italian counterparts

also involved the exchange of officers and technology, if not a small

amount of raw material as well. Some of the missing uranium probably

also fell into the hands of the Soviets as the Russian armies steamrollered

into Eastern Europe and finally into what would become the Soviet

"eastern" zone of occupation in Germany.

But why, after traveling under radio silence from

Germany, did the U-234 finally surrender its precious uranium, fuses,

and "water", when its obvious destination was Japan? This

is an intriguing question, and one that unfortunately cannot be answered

here except briefly. Again, Carteer Hydrick's superb research elaborates

one highly probable hypothesis: U-234 was handed over to the US authorities

on the orders of none other than Martin Bormann, in a maneuver designed

to secure his and others' freedom after the war, and as part of a

deliberate plan to continue Nazism and its agendas and research underground.18

17Q.v. chapter 7.

18 Q.v. part two. The allegation that Bormann's action

was a component of this plan is my own, and not Hydrick's although

Hydrick also clearly suggests a connection. This "Bormann hypothesis"

of the events leading up to the U-234's surrender is a major component of Hydrick's work,

spanning several pages of meticulous research.

It is thus, on this view, the first visible, and crucial, element of the emerging

Operation Paperclip, the transfer of technology amid scientists from

the collapsing Third Reich to the United States. There, the German

scientists and engineers could, would, and did continue their lines

of esoteric research and development of high technology and sophisticated

weaponry, with a similar moral and ideological effect on the culture

at large as occurred in Nazi Germany.

And finally, of course, as we have already seen,

some of the missing uranium ended up in the German atom bomb program

itself, enriched, and refined, and probably assembled and tested -

if not used - in actual bombs themselves.

Back to Contents