by Tyler Durden

November 19, 23011

from

ZeroHedge Website

"Nervous investors around the globe are

accelerating their exit from the debt of European governments and banks,

increasing the risk of a credit squeeze that could set off a downward

spiral.

Financial institutions are dumping their

vast holdings of European government debt and spurning new bond issues

by countries like Spain and Italy. And many have decided not to renew

short-term loans to European banks, which are needed to finance

day-to-day operations."

So begins an article not in some

hyperventilating fringe blog, but a cover article in the venerable New York

Times titled "Europe Fears a Credit Squeeze as Investors Sell Bond

Holdings."

Said otherwise, Europe's continental bank run in

which virtually, but not quite, all banks are dumping any peripheral

exposure with reckless abandon is now on.

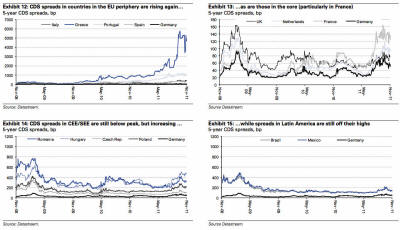

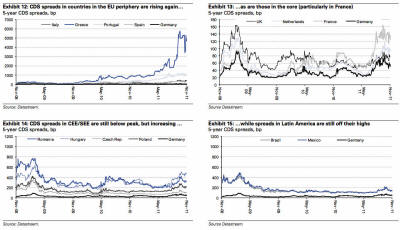

Granted, considering the epic collapse in bond

prices of Italian, French, Austrian, Hungarian, Spanish and Belgian bonds

which all hit record wide yields and spreads in the past week, and

furthermore following last week's "Sold

To You": European Banks Quietly Dumping €300 Billion In Italian Debt"

which predicted precisely this outcome, the news is not much of a surprise.

However, learning that everyone (with two

exceptions) has given up on Europe's financial system should send a shudder

through the back of everyone who still is capable of independent thought -

because said otherwise, the world's largest economic block is becoming

unglued, and its entire financial system is on the edge of a complete

meltdown.

And just to make sure that various fringe

bloggers who warned this would happen over a year ago no longer lead to the

hyperventilation of the venerable NYT, below, with the help of Goldman's

Jernej Omahan, we bring to our readers the complete annotated and

abbreviated beginner's guide to the pan-European bank run.

But first some more details

from the NYT:

The flight from European sovereign debt and

banks has spanned the globe.

European institutions like the Royal Bank of

Scotland and pension funds in the Netherlands have been heavy sellers in

recent days. And earlier this month, Kokusai Asset Management in Japan

unloaded nearly $1 billion in Italian debt.

At the same time, American institutions are pulling back on loans to

even the sturdiest banks in Europe.

When a $300 million certificate of deposit

held by Vanguard’s $114 billion Prime Money Market Fund from Rabobank in

the Netherlands came due on Nov. 9, Vanguard decided to let the loan

expire and move the money out of Europe. Rabobank enjoys a AAA-credit

rating and is considered one of the strongest banks in the world.

American money market funds, long a key supplier of dollars to European

banks through short-term loans, have also become nervous.

Fund managers have cut their holdings of

notes issued by euro zone banks by $261 billion from around its peak in

May, a 54 percent drop, according to JPMorgan Chase research.

Is this setting familiar to anyone?

It should

be:

"Experts say the cycle of anxiety, forced

selling and surging borrowing costs is reminiscent of the months before

the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, when worries about subprime

mortgages in the United States metastasized into a global market

crisis."

Ah, but there is one major difference: last time

around, the banks were not all in on the wrong side of the world's worst

poker hand (as described by Kyle Bass earlier). Now they are.

And should Europe's banks begin a domino-like

spiral of collapse, there will be nobody to bail out first Europe, then

Japan, then China, then the US and finally the world.

But lest someone suggest this is merely the deranged ramblings of yet

another blogger, here is Goldman Sachs with a far more cool, calm and

collected explanation for why we should all panic (which comes at the

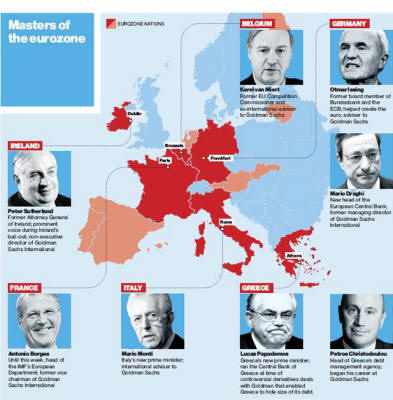

sublime moment: just as Goldman takes over all the key political locus

points of the European continent: more on that in the conclusion...)

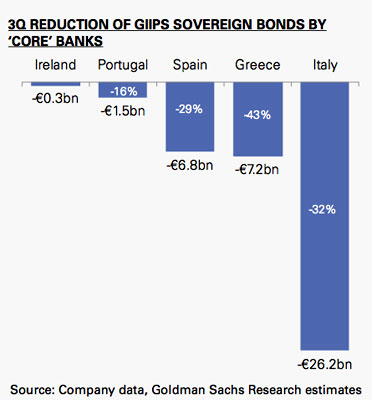

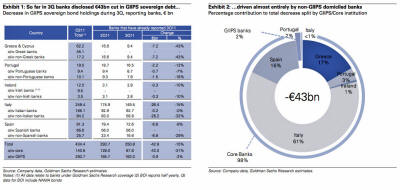

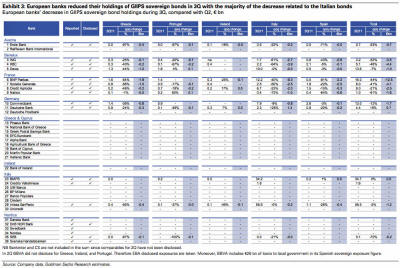

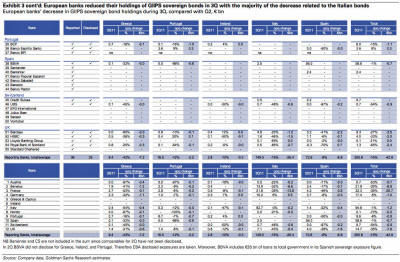

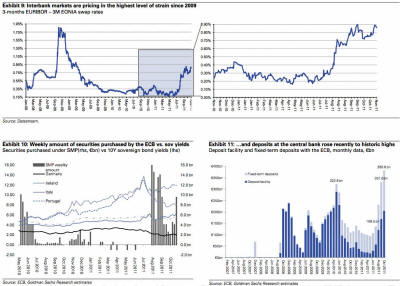

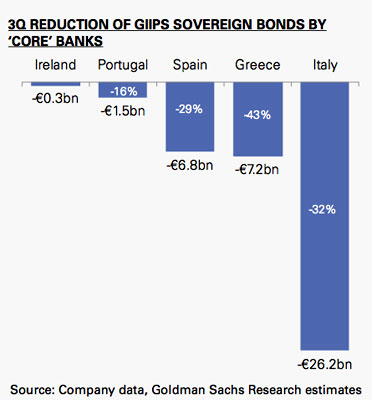

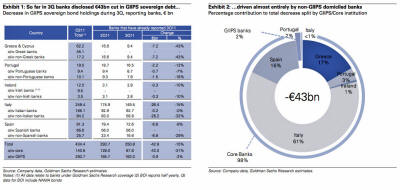

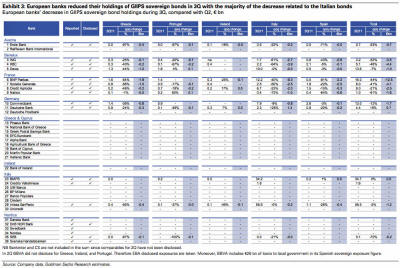

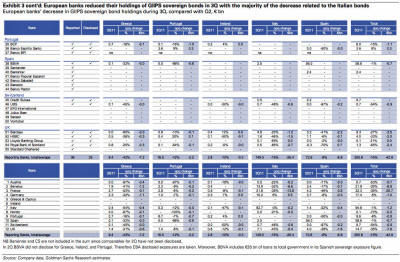

Core’ banks cut GIIPS debt by €42 bn (-31%) in 3Q

- A manifestation of PSI side-effects?

In 3Q2011, banks from the ‘core’ cut

their net GIIPS (alternative spelling of

PIIGS) sovereign debt holdings by €42 bn (or by one-third),

mostly,

French and Benelux banks cut their exposures

most, by €21 bn and €9 bn, respectively. GIIPS portfolios remained

unchanged with periphery banks.

Greek PSI sets a risky precedent, in our

view, as the prospect of ‘voluntary’ haircuts becoming a template for

GIIPS crisis resolution could drive exposure reduction.

Core banks now have €88 bn of GIIPS

sovereign bonds remaining. We expect this to decline.

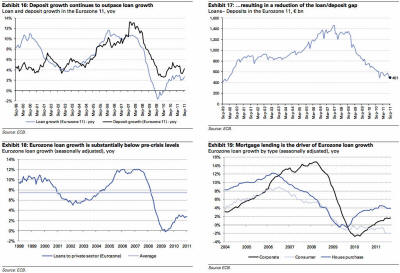

Problematically, we observe that GIIPS bond

reductions are not resulting in ‘core’ bond purchases but in a rise in

deposits at the ECB.

-

The disposal of GIIPS sovereign debt

accelerated during 3Q2011, and we highlight the following.

-

Banks cut net GIIPS sovereign

exposure by €43 bn.

-

The largest reductions relate to Italian

(€26 bn), Spanish (€7 bn) and Greek (€7 bn) net sovereign debt

positions.

-

Almost all of the reduction (€42 bn)

came from banks in the European ‘core’, where the GIIPS bond

positions therefore fell by just over one-third (31%).

-

At the

same time the banks from the ‘periphery’ kept their exposures

unchanged.

-

French (€21 bn) and Benelux (€9 bn)

banks reduced their exposure most.

-

Individually BNP (€12 bn), KBC (€4.4

bn), SG (€4.1 bn), BARC (€3.5 bn) and ING (€3.5 bn) cut the net

sovereign exposures most, in absolute terms.

We expect this trend to extend into 4Q and

to ultimately lead to a long-term reduction GIIPS bond holdings by core

banks.

Greek PSI - and the ‘voluntary’ 50% haircut - has changed the risk

perception of GIIPS bonds. We believe it has allowed for an assumption

that PSI will be used as a template in helping other GIIPS sovereigns

improve their public finances. Such intention is denied by policy

makers. Banks, on the other hand, express their view of the likelihood

of such an event through the changes in their net positions.

It is important to emphasizes that a bank’s decision to hold sovereign

debt is not an expression of an investment preference.

Rather, it is a decision related to

liquidity management. As such banks seek ‘risk free’ assets that can be

used to access liquidity at any time, particularly at the time of

crisis. Regulators continue to treat sovereign debt as highest-quality

and risk free (0% risk-weight) collateral.

With no RWA constraint and full refinancing

eligibility, banks are encouraged to hold sovereign debt; its

(selective) transition from a ‘risk free’ to a ‘risk’ asset is therefore

unexpected and highly damaging.

Earlier we said all but two entities have been

dumping PIIGS (or GIIPS as Goldman prefers to call them).

Sure enough, one of the unlucky two tasked with

buying everything sold in the secondary market is of course the ECB: the

same bank that everyone is accusing of not doing more to help.

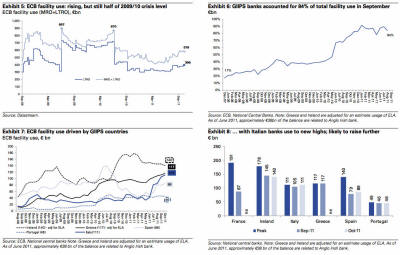

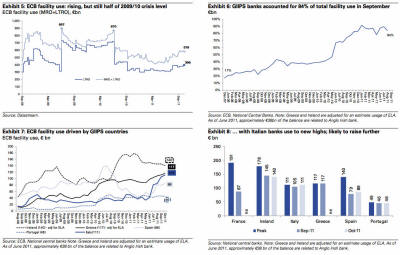

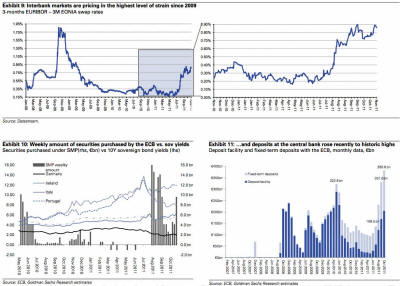

Funding - Increasingly reliant on the ECB

The use of ECB facilities rose again

in October, driven by Spanish (€7 bn) and Italian (€6 bn) banks.

For 4Q, we expect a sharp increase in use by

Italian banks, driven by:

-

LCH’s increased margin requirements on

Italian REPOs, which now make market REPOs comparatively more expensive

than those at the ECB;

-

a steady fading of the ECB funding

‘stigma’

It is possible that the majority of the €300

bn of interbank funding and market REPOs could end up on ECB’s balance

sheet.

That alone would have the capacity to lift current ECB use from

€579 bn to just below €900 bn. This level of use would compare with

previous crisis peak levels (2009) of €870-897 bn.

We have long argued that the ECB has capacity to back-stop bank funding

requirements - and there is no change to this view. That said, a gradual

closing of the last functioning wholesale funding market - short-term

REPOs, backed by government bonds - is certainly not an encouraging

sign.

The re-opening of the long-term funding

markets has been pushed further out, in our view.

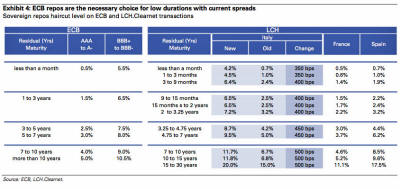

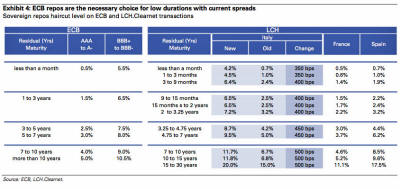

LCH triggers increased margin requirements

on Italian REPOs

On November 9, 2011, LCH.

Clearnet (LCH) announced its decision to

increase ‘deposit factors’ applied to Italian debt repo transactions

(e.g. haircut on collateral) by 3.5% to 5% depending on the duration of

the collateral.

The move was not a surprise as LCH’s Risk

Management Framework states that it,

“would generally consider a spread of

450bp over the 10-year AAA benchmark to be indicative of additional

sovereign risk”, which may cause it to “materially increase the

margin required for positions in that issuer”.

Previously, ECB interventions kept the

spreads below the key trigger level of 450bp.

Italian banks likely to switch to the ECB

Owing to increased margin

requirement, market REPOs have become more expensive. In our view, the

banks are therefore likely to look for alternative sources of funding,

especially with the ECB.

Typically, the cost a bank faces to fund a sovereign bond portfolio

through a tri-party repo transaction consists of:

-

the funding rate (‘repo rate’) for

the duration of the repo and applied to the market value of the

bonds

-

additional funding costs, mostly in

the form of the haircut/margin required by the Central Clearing

House as collateral

The higher the haircut/margin level and the

marginal funding cost, the higher the cost of the borrowing, which

becomes ineffective when it exceeds the cost of the ECB repo facility

(1.5% repo rate + haircut funding cost).

The Italian banks’ funding currently includes €155 bn of customer repos

and €193 bn of interbank funding exposure to non resident MFIs. The

large portion of the latter takes the form of secured funding (repos).

In addition, the Italian banks currently draw on €111 bn of ECB funding.

It is possible that the majority of the €300 bn of interbank funding and

market REPOs could end up on the ECB’s balance sheet. That alone would

have the capacity to lift current ECB use from €579 bn to just below

€900 bn.

This level of use would compare with

previous crisis peak levels (2009) of €870-897 bn.

So just why again is it that anyone accuses the

ECB of doing nothing?

When all is said and done under the current

regime, the ECB balance sheet will be just under €2 trillion, and that is

without any incremental printing, courtesy of the farce that is

"sterilization" with banks which exist only due to the ECB, thereby making

said sterilization about the most idiotic thing ever conceived.

Yet that is

what spin is for...

In the meantime, the European shadow banking system is on the verge of a

complete shutdown, with repos of all shapes and sizes about go dark.

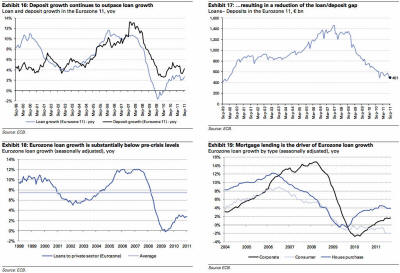

And summarizing all of the above visually, here come the charts:

And while we already discussed that one half of

Europe's dumb money is the ECB by necessity, to get the answer for who is

the other half we go back to our post from last Friday:

Completing the picture is the answer of who

the dumb money is:

Italian bonds still have one support

bloc.

Domestic banks appear to be holding on

to their much larger holdings. As of last December, EBA stress tests

showed Intesa Sanpaolo held €60bn of Italian debt. UniCredit and

Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena held €49bn and €32bn respectively.

Recent results indicate that those

holdings have changed little.

“We will keep investing the largest

part of our liquidity in Italian government bonds,” said Corrado

Passera, chief executive officer at Intesa Sanpaolo, in a call

with analysts this week.

“We believe they provide the right

yields vis-à-vis the cost. So no policy change on our side.”

Still, according to the investment

banker advising firms on their Italian holdings, the domestic banks’

decisions to hold on could have more to do with their inability to

offload such large amounts quickly and without deep losses. Indeed,

some Italian bankers seem resigned to the situation.

Capital concerns are also preventing them from selling.

“The key issue is on solvency and I

think they made a mistake in requiring us to hold more capital,”

said the chief executive of a mid-sized Italian bank.

“To meet these levels we cannot sell

too much of our sovereign debt.”

So instead of selling, Italian banks are

doing all they can to dodecatuple down and... buy!?

To summarize

Everyone is dumping European paper, except for

the ECB and Italian banks, which have no choice and instead have to double

down and buy more.

In the meantime, the market is going

increasingly bidless as liquidity evaporates, confidence has disappeared and

virtually everyone now expects a repeat of Lehman brothers. Of course, this

means that when the bottom finally out from the market, the implosion of the

Italian banking system, and thus economy, will be instantaneous.

And when Italy goes, so goes its $2 trillion+ in

sovereign debt, and at that point we will see just how effectively hedged

and offloaded the rest of the world is, as contagion shifts from Italy and

slowly but surely engulfs the entire world.

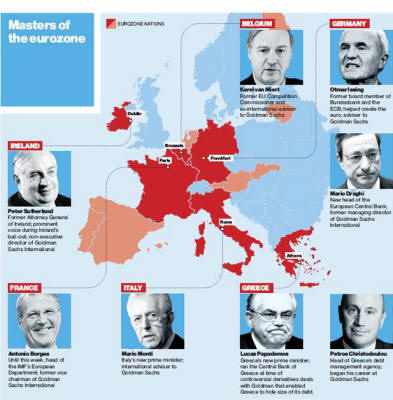

Incidentally, is it really that surprising that Goldman is now doing its

best to precipitate a bank run of Europe's major financial institutions by

"suddenly" exposing the truth that was there all along? During the great

financial crisis of 2008, the one biggest winner from the collapse of Bear

and Lehman was none other than the squid.

This time around, Goldman has set its sights on

Europe and has already made sure that its tentacles will be in firmly in

control at all the right places when the collapse comes, as

the Independent shows.

And when banks are falling over like houses of

cards in the middle of a tornado cluster, and the financial power vacuum is

in desperate need to be filled, who will step in once again but... Goldman

Sachs.

Video

'Goldman Sachs Dictatorship - Hitler's Dream'

by

RussiaToday

December 7, 2011

from

YouTube Website

Time is running out for Eurozone leaders to save the single currency, as

they prepare for eleventh-hour talks in Brussels. Germany and France are

pushing to change EU treaties, to create a fiscal union and introduce

tougher budget rules.

However, the European Council President believes they

can achieve the same goals without altering existing treaties, which would

need a lengthy ratification process.

The British Prime Minister warned he

wouldn't agree to anything which damaged the UK's role in the European

market. Meanwhile, credit ratings giant Standard and Poor's has added to the

sense of urgency, as it threatens to downgrade 15 Eurozone countries as well

as their bailout fund.

Investigative journalist Tony Gosling says countries

need to return to their own currencies if they're to escape being ruled by

Brussels.