|

from

WolfStreet Website

Something is changing about the perception of the Fed's free-money policies.

While we've lambasted them for their nefarious effects on the real economy and the inequality they produce, Wall Street, the prime beneficiary, has been bombastically gung-ho about them.

And the mainstream media have praised the Fed's "bold action," as it's called, at every twist and turn. But now even Wall Street is getting cold feet.

The official warning shot came from Fed Chair Janet Yellen, who admitted suddenly that,

Then bankers chimed in.

FICO, which produces the infamous credit score, found in its latest survey of North American bank risk managers that 62% of them thought,

With the economy so dependent on consumer spending,

This is a twist:

Turns out, in our consumer-based economy, most consumers no longer have the means to adequately support that economy; and the few who have benefited from the wealth redistribution scheme, are too few to adequately support the economy.

And they fret that this inequality is,

Suddenly the equation no longer works. Wall Street doesn't want a revolt.

Now even the New York Times, the indefatigable proponent of QE and ZIRP, ran an editorial that explained how QE and ZIRP,

William Cohan, a former M&A banker, quoted at length from Yellen's inequality speech.

Then he slammed into her:

That this shows up in the New York Times says something - maybe that QE is becoming politically untenable, that it's no longer cool to shove free trillions from all over the place into just one small corner of the economy.

Not because it isn't fair somehow, but because it wipes out consumers who are supposed to move the economy forward.

The anecdotal signs of consumers in trouble are everywhere. But they're partially obscured in our statistics by, among other factors, inflation and population growth.

Retail sales in September, seasonally adjusted, declined 0.3% month-over-month, and while that was somewhat of a cold shower, retail sales have been rising.

Doug Short of Advisor Perspectives explains:

But the retail sales report isn't adjusted for inflation, and it isn't adjusted for population growth.

When we want to find out real spending per consumer to see how each consumer is contributing to the economy - that's what we actually see here on the ground - the effects of the wealth transfer become apparent.

As Doug writes,

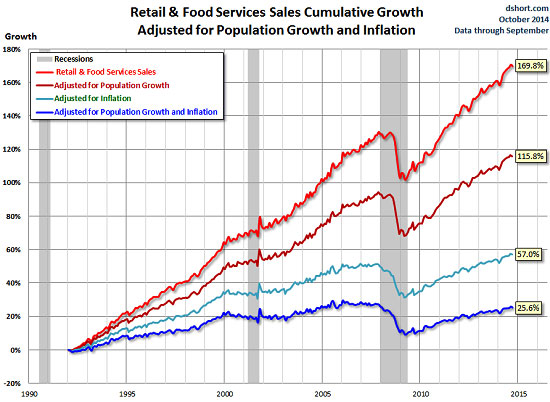

The chart below (his article including methodology is here) shows how much retail sales growth is a function of inflation and population growth.

Reported retails sales (red line, top) are up a whopping 169.8% since 1992. Fluctuations have been relatively minor, except for the collapse during the Financial Crisis. But since 1992, the population has grown 25% and the dollar has lost 42% of its purchasing power thanks to the Fed's proudest achievement, inflation.

Now look at the stagnating blue line at the bottom: retails sales adjusted for population growth and inflation are up only 25.6% over the past 22 years.

They're now at a level first seen in December 2004!

Based on this method, September retail sales dropped 0.5% from August and are only up 1.9% year-over-year.

While they've recovered since the horror levels of 2009, they remain 3.3% below the peak of January 2006. That's what the Fed's "bold actions" have accomplished.

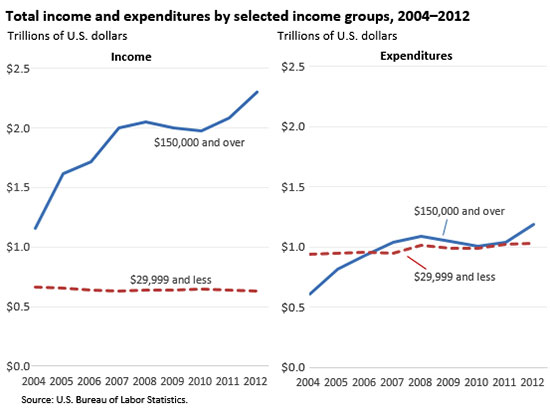

What this chart doesn't show is the bifurcation in retail sales; but a report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics does: those at the lower-income levels, those who've gotten ripped off by inflation, have become terrible consumers in our economy that is so dependent on consumer spending.

Note that the chart is not adjusted for inflation. If it were, it would look even more terrible.

Without thriving consumers, the American economy that is so dependent on them will continue to languish.

Just adding more consumers to the mix may increase overall consumer spending, and stirring up inflation may cover up the issue. But as the majority of individual consumers falls further behind, the risks of financial, social, or political "instability" might be looking ever more plausible to those bankers.

So is the FED now on the hot seat for its policies?

Now that bankers, Yellen, and even the New York Times are showing a modicum of doubt, are these the first signs that there is finally some resistance building up? If this is the case, perhaps, just perhaps, you can kiss QE - and with a little patience, ZIRP - goodbye.

And just perhaps, it's already dawning on skittish market participants what this might do to pandemic asset price inflation.

One big investor already reacted to a ludicrously inflated asset price.

|