|

by Dan Mitchell

11 February 2015

from

InternationalMan Website

|

Dan Mitchell is an

economist and senior fellow at the Cato Institute. He's

a strong proponent of tax competition, financial

privacy, and fiscal sovereignty. You can read his blog

here. |

Tax havens have a valuable role in the global economy.

They facilitate the efficient allocation

of capital; they encourage saving and investment; and because of

tax competition, they encourage

better policy in the rest of the world.

As noted in the New England Journal of International and

Comparative Law, tax competition serves a beneficial role. It

forces greater fiscal responsibility and affords taxpayers the

ability to enjoy more of what they earn. This in turn draws savings

investment and skilled labor into the economy.

But economic efficiency isn't the only reason that

tax havens should be preserved.

These low-tax jurisdictions also should be defended on a moral

basis.

Most notably, they offer a safe haven

for people subject to persecution.

It isn't very well understood that the vast majority of the world's

population lives in nations where governments fail to provide the

basic protections of civilized society. Indeed, in many cases,

governments are the problem, as corrupt ruling elites use their

power to exploit people. Corruption often is rampant, expropriation

is common, crime is endemic, and there's widespread persecution.

Not surprisingly, people with money are common targets of

oppression, particularly if they're a religious, political, ethnic,

racial, and/or sexual minority.

Tax havens help protect these people from venal and incompetent

governments by providing a secure place to hide their assets.

Indeed, one of the reasons why Switzerland has such an admirable

human rights policy of protecting financial privacy is that it

strengthened its laws in the 1930s to help protect German Jews who

wanted to guard their assets from the Nazis.

Many groups in the world face discrimination and hostility, often

from government.

The ethnic Chinese in nations such as Indonesia and the Philippines

often are resented by the local population. The same is true for

people of Indian descent in East Africa.

When you belong to a group that is unpopular and susceptible to

being targeted by the government, it makes sense to protect your

family's interest by putting your money someplace like Hong Kong,

where the politicians from your country can't find out about it. If

they can't find out about it, they can't steal it.

In other words, the financial privacy laws that make tax havens so

attractive to French families and Swedish entrepreneurs who want to

escape oppressive taxation are the same laws that protect other

people from different forms of persecution.

Let's look at the example of political dissidents from places such

as Russia or any of the 107 nations listed as "not free" or "only

partly free" by

Freedom House. These people (or the

civil society groups that they operate) have a big incentive to keep

their money where the political elite can't seize it.

Imagine if you're a farmer in Zimbabwe. Would you want to leave your

assets in a local bank where the nation's dictator can arbitrarily

confiscate your money?

Of course not.

You're going to put your money in a

jurisdiction that's honest and well run, such as the Cayman Islands.

-

Or what about the Argentine

family that wisely has little faith in its government's

ability to maintain the value of currency?

-

Would you want to leave your

money in a local bank, oblivious to the risk that your

family's life savings could be wiped out overnight by

devaluation?

-

Or what if you're an

entrepreneur in Venezuela?

-

Do you keep your assets in the

nation and report them on your tax return when there is

corruption in the tax office and your personal data may be

sold to kidnappers, who then grab one of your kids?

If you have any sense whatsoever, you

place your money in a bank in Miami, since America is a tax haven -

at least, if you aren't a US citizen or US resident.

International bureaucracies such as,

...are attacking tax havens as part of a

campaign orchestrated by high-tax nations. Uncompetitive governments

don't like tax competition; they instead would prefer to create a

global tax cartel - sort of an OPEC for politicians.

With this in mind, it's remarkable that even the international

bureaucracies acknowledge the valuable role of tax havens on

financial privacy.

The United Nations, for instance, admitted in a 1998 report that for

much of the 20th century, governments around the

world spied on their citizens to maintain political control.

Political freedom depends on the ability to hide purely personal

information from a government. Too bad the UN bureaucrats are

ignoring these warnings and pushing for global taxation.

But

the United Nations isn't the only

hypocritical organization.

A former leader of the OECD's anti-tax

competition project, Jeffrey Owens, recognized the role of

tax havens as protectors of human rights. As reported by the UK

based Observer, Owens stressed that tax havens are essential for

individuals who live in unstable regimes.

Even a former Clinton-era Treasury

Department official who was closely involved with the OECD's

anti-tax competition campaign admitted,

"[H]ow far do we want to go with

this information exchange and the secrecy issues, the privacy

issues and so forth, which relates to the problems of corrupt

governments, a danger to your children and to individuals? That

subject should be discussed."

Let's quickly touch on a few other moral

issues.

The campaign against tax havens interferes with the right of

jurisdictions to pursue pro-growth policies, which is especially

discriminatory against poor nations.

Having no or low taxes is the main

criterion for being listed as a tax haven by the OECD, yet most OECD

nations didn't have income taxes during the 1700s and 1800s, which

was the period of time when they climbed from agricultural poverty

to middle-class prosperity.

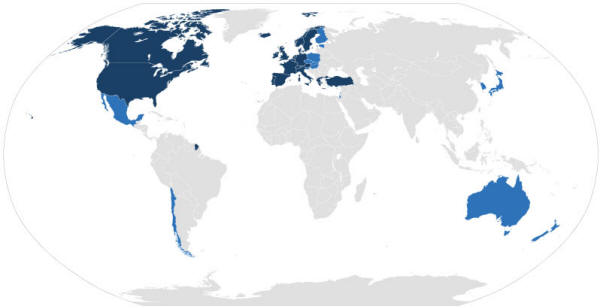

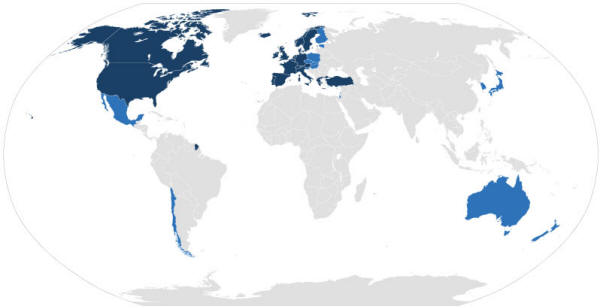

OECD Member

States

We should all be offended that nations such as France and Germany

became rich when they had no income tax, and now they want to deny

that opportunity to poor nations that want to follow the same

development strategy.

Speaking of discrimination, it's also a bit unseemly that powerful

nations in Europe are targeting less powerful jurisdictions from

places such as the Caribbean. Somebody needs to tell the bureaucrats

in Paris that the era of colonialism is over.

Another issue is the OECD's hypocritical treatment of capital

compared to labor. The Paris-based bureaucracy is upset that

investment funds are flowing to low-tax jurisdictions, many of which

are in the developing world.

But OECD nations are big beneficiaries

of a brain drain from developing nations.

This flow of talent is very beneficial

for labor inflow nations, just as global financial flows are very

beneficial for capital inflow nations. Yet the OECD isn't suggesting

that developing nations have the right to tax immigrant income

earned in OECD nations, so why should OECD nations be allowed to tax

flight capital in non-OECD nations?

Speaking of hypocrisy, what about the fact that the OECD doesn't

blacklist its own members?

The United States, the United Kingdom,

Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, and Luxembourg are all OECD member

nations; yet they weren't on the OECD's blacklist. Only smaller,

less powerful nations were subject to this form of discrimination.

Of course, the ultimate hypocrisy of all is that the bureaucrats who

work at the OECD and the United Nations all get tax-free salaries -

while they're running around the world trying to demand that other

nations raise their taxes.

Politicians from high-tax nations and their flunkies at the

international bureaucracies often admit that the moral issues raised

in this article are very pertinent, but they then say that they're

worried that tax havens enable some of their residents to avoid the

tax net.

-

But why is that the fault of

jurisdictions with better tax policies?

-

If high-tax nations want better

compliance, shouldn't they fix their tax systems instead of

trying to bully other nations into surrendering their fiscal

sovereignty and becoming vassal tax collectors?

|