|

by Tyler Durden

September 06, 2015

from

ZeroHedge Website

Why did we focus so

much attention yesterday on a post

in which

the IMF confirmed what we had said

since last October, namely that the BOJ's days of ravenous debt

monetization are coming to a tapering end as soon as 2017 (as

willing sellers simply run out of product)?

Simple:

because in the global fiat regime,

asset prices are nothing more than an indication of central

bank generosity.

Or, as Deutsche Bank puts it:

"Ultimately in a fiat money

system asset prices reflect "outside" i.e. central bank

money and the extent to which it multiplied through the

banking system."

The problem is that the

BOJ and the

ECB are the only two remaining

central banks in a world in which Reverse

QE aka "Quantitative Tightening" in

China, and the FED's tightening in the form of an upcoming rate hike

(unless

the FED loses all credibility and

reverts its pro-rate hike bias), are now actively involved in

reducing global liquidity.

It is only a matter of time before the

market starts pricing in that the Bank of Japan's open-ended QE has

begun its tapering (followed by a QE-ending) countdown, which will

lead to devastating risk-asset consequences.

The ECB, which is also greatly supply

constrained as Ewald Nowotny

admitted yesterday, will follow

closely behind.

But while we expanded on the Japanese

problem to come

in detail yesterday, here are some

key observations on what is going on in both the U.S. and China

as of this moment -

the two places which all now admit are the culprit for the recent

equity selloff, and which the market has finally realized are

actively soaking up global liquidity.

Here the problem, as we initially

discussed

last November in "How

The Petrodollar Quietly Died, And Nobody Noticed", is

that as a result of the soaring U.S. dollar and collapse in oil

prices, Petrodollar recycling has crashed, leading to an outright

liquidation of FX reserves, read U.S. Treasury's by emerging market

nations.

This was reinforced on August 11th

when China joined the global liquidation push as a result of its

devaluation announcement, a topic which we also covered far ahead of

everyone else with our May report "Revealing

The Identity Of The Mystery 'Belgian' Buyer Of U.S. Treasurys",

exposing Chinese dumping of U.S. Treasury's via Belgium.

We also hope to have made it quite clear

that China's reserve liquidation and that of

the EM petro-exporters is really

two sides of the same coin:

in a world in which the USD is

soaring as a result of FED tightening concerns, other central

banks have no choice but to liquidate FX reserve assets: this

includes both EMs, and most recently, China.

Needless to say, these key trends

covered here over the past year have finally become the biggest

mainstream topic, and have led to the biggest equity drop in years,

including the first correction in the S&P since 2011.

Elsewhere, the risk devastation is much

more profound, with emerging market equity markets and currencies

crashing around the globe at a pace reminiscent of the Asian 1998

crisis, while in China both the housing and credit, not to mention

the stock market, bubble have all long burst.

Before we continue, we present a brief

detour from Deutsche Bank's Dominic Konstam on precisely how

it is that in the current fiat system, global central bank liquidity

is fungible and until a few months ago, had led to record equity

asset prices in most places around the globe.

To wit:

Let's start from some basics.

Global liquidity can be thought

of as the sum of all central banks' balance sheets (liabilities

side) expressed in dollar terms.

We then have the case of completely

flexible exchange rates versus one of fixed exchange rates. In

the event that one central bank, say the FED, is expanding its

balance sheet, they will add to global liquidity directly.

If exchange rates are flexible this

will also mean the dollar tends to weaken so that the value of

other central banks' liabilities in the global system goes up in

dollar terms.

Dollar weakness thus might

contribute to a higher dollar price for dollar denominated

global commodities, as an example.

If exchange rates are pegged then to achieve that peg other

central banks will need to expand their own balance sheets and

take on dollar FX reserves on the asset side.

Global liquidity is therefore

increased initially by the FED but, secondly, by further

liability expansion, by the other central banks.

Depending on the sensitivity of

exchange rates to relative balance sheet adjustments, it is not

an a priori case that the same balance sheet expansion by the

FED leads to greater or less global liquidity expansion under

either exchange rate regime.

Hence the mere existence of a

massive build up in FX reserves shouldn't be viewed as a massive

expansion of global liquidity per se - although as we shall show

later, the empirical observation is that this is a more powerful

force for the "impact" of changes in global liquidity on

financial assets.

That, in broad strokes, explains how and

why the FED's easing, or tightening, terms have such profound

implications not only on every asset class, and currency pair, but

on global economic output.

Liquidity in the broadest sense tends to support

growth momentum, particularly when it is in excess of current

nominal growth.

Positive changes in liquidity should

therefore be equity bullish and bond price negative. Central

bank liquidity is a large part of broad liquidity and, subject

to bank multipliers, the same holds true.

Both FED tightening and China's FX

adjustment imply a tightening of liquidity conditions that, all

else equal, implies a loss in output momentum.

But while the impact on global economic

growth is tangible, there is also a substantial delay before its

full impact is observed.

When it comes to asset prices, however,

the market is far faster at discounting the disappearance of the

"invisible hand":

Ultimately in a fiat money system

asset prices reflect "outside" i.e. central bank money and the

extent to which it multiplied through the banking system. The

loss of reserves represents not just a direct loss of outside

money but also a reduction in the multiplier.

There should be no expectation that

the multiplier is quickly restored through offsetting central

bank operations.

Here Deutsche Bank suggests your panic,

because according to its estimates, while the U.S. equity market may

have corrected, it has a long ways to go just to catch up to the

dramatic slowdown in global plus FED reserves (that does not even

take in account the reality that soon both the BOJ and the ECB will

be forced by the market to taper and slow down their own liquidity

injections):

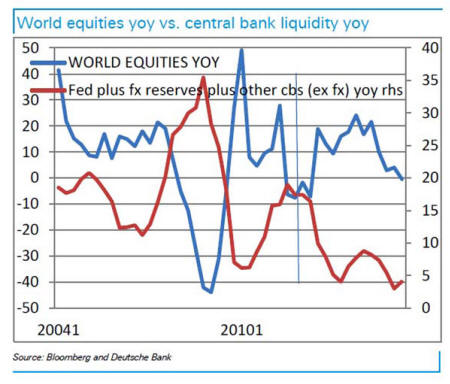

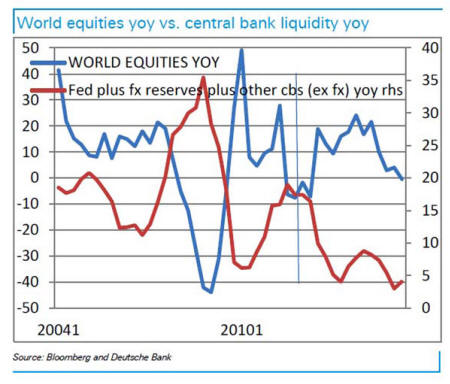

Let's start with risk assets,

proxied by global equity prices.

It would appear at first glance

that the correlation is negative in that when central bank

liquidity is expanding, equities are falling and vice versa. Of

course this likely suggests a policy response in that central

banks are typically "late" so that they react once equities are

falling and then equities tend to recover.

If we shift liquidity forward 6

quarters we can see that the market "leads" anticipated"

additional liquidity by something similar.

This is very worrying now in that it suggests that equity price

appreciation could decelerate easily to -20 or even 40 percent

based on near zero central bank liquidity, assuming similar

multipliers to the post crisis period.

Some more dire predictions from Deutsche

on what will happen next to equity prices:

If we only consider the FX and FED

components of liquidity there appears to be a tighter and more

contemporaneous relationship with equity prices.

The suggestion is at one level still

the same, absent FED and FX reserve expansion,

equity prices look more likely

to decelerate and quite sharply.

The FED's balance sheet for

example could easily be negative 5 percent this time next year,

depending on how they manage the SOMA portfolio and would be

associated with further FX reserve loss unless countries,

including China allowed for a much weaker currency.

This would be a great concern for global (central

bank liquidity).

Once again, all of this assumes a status

quo for the QE out of Europe and Japan, which as we pounded the

table yesterday, are both in the process of being "timed out"

The tie out, presumably with the

"leading" indicator of other central bank action is that other

central banks have been instrumental in supporting equities in

the past.

The

largest of course being the ECB and BoJ.

If the FED isn't going doing its

job, it is good to know someone is willing to do the job for

them, albeit there is a "lag" before they appreciate the extent

of someone else's policy "failure".

Worse, as noted yesterday soon there

will be nobody left to mask everyone one's failure: the global

liquidity circle jerk is coming to an end.

What does this mean for bond yields?

Well, as we explained previously, clearly the selling of TSYs by

China is a clear negative for bond prices.

However, what Deutsche Bank accurately

notes, is that should the world undergo a dramatic plunge in risk

assets, the resulting tsunami of residual liquidity will most likely

end up in the long-end, sending Treasury yields lower.

To wit:

...if investors believe that liquidity is likely

to continue to fall one should not sell real yields but buy them

and be more worried about risk assets than anything else.

This flies in the face of recent

concerns that China's potential liquidation of Treasuries for FX

intervention is a Treasury negative and should drive real yields

higher....

More generally the simple point is that falling reserves should

be the least of worries for rates - as they have so far proven

to be since late 2014 and instead, rates need to focus more on

risk assets.

The relationship between central bank liquidity

and the byproduct of FX reserve accumulation is clearly central

to risk asset performance and therefore interest rates.

The simplistic error is to assume that

all assets are treated equally.

They are not - or at least have not

been especially since the crisis.

If liquidity weakens and risk assets

trade badly, rates are most likely to rally not sell off.

It doesn't matter how many

Treasury bills are redeemed or USD cash is liquidated from

foreign central bank assets, U.S. rates are more likely to fall

than rise especially further out the curve. In some

ways this really shouldn't be that hard to appreciate.

After all central bank liquidity drives broader

measures of liquidity that also drives, with a lag, economic

activity.

Two points:

we agree with DB that if the market

were to price in collapsing "outside" money, i.e. central bank

liquidity, that risk assets would crush (and far more than just

the 20-40% hinted above).

After all it was central bank

intervention and only central bank intervention that pushed the

S&P from 666 to its all time high of just above 2100.

However, we also disagree for one

simple reason: as we explained in "What

Would Happen If Everyone Joins China In Dumping Treasuries",

the real question is what would

everyone else do.

If the other EMs join China in

liquidating the combined $7.5 trillion in FX reserves (i.e.,

mostly U.S. Treasuries but also those of Europe and Japan) shown

below...

... into an illiquid Treasury bond

market where central banks already hold 30% or more of all 10

Year equivalents (the BOJ will own 60% by 2018), then it is

debatable whether the mere outflow from stocks into bonds will

offset the rate carnage.

And, as we showed before, all else

equal, the unwinding of the past decade's accumulation of EM

reserves, some $8 trillion, could possibly lead to a surge in

yields from the current 2% back to 6% or higher.

In other words, inductively reserve

liquidation may not be a concern, but practically - when taking in

account just how illiquid the global TSY market has become - said

liquidation will without doubt lead to a surge in yields, if only

occasionally due to illiquidity driven demand discontinuities.

***

So where does that leave us?

Summarizing Deutsche Bank's

observations:

they confirm everything we have said

from day one, namely that the QE crusade undertaken first by the

FED in 2009 and then all central banks, has been the biggest

can-kicking exercise in history, one which brought a few years

of artificial calm to the market while making the wealth

disparity between the poor and rich the widest it has ever been

as it crushed the global middle class; now the end of QE is

finally coming.

And this is where Deutsche Bank,

which understands very well that the FED's tightening coupled

with Quantiative Tightening, would lead to nothing short of a

global equity collapse (especially once the market prices in the

inevitable tightening resulting from the BOJ's taper over the

coming two years), is shocked.

To wit:

This reinforces our view that the FED is in

danger of committing policy error.

Not because one and done is a

non issue but because the market will initially struggle to

price "done" after "one". And the FED's communication skills

hardly lend themselves to over achievement.

More likely in our view, is

that one in September will lead to a December pricing and

additional hikes in 2016, suggesting 2s could easily trade to 1

¼ percent.

This may well be an overshoot but it could imply

another leg lower for risk assets and a sharp reflattening of

the yield curve.

But it was the conclusion to Deutsche's

stream of consciousness that is the real shocker: in it DB's

Dominic Konstam implicitly ask out loud whether what comes next

for global capital markets (most equity, but probably rates as

well), is nothing short of a controlled demolition.

A

premeditated controlled demolition, and facilitated by

the FED's actions or rather lack thereof:

The more sinister undercurrent is

that as the relationship between negative rates has tightened

with weaker liquidity since the crisis,

there is a sense that policy is

being priced to "fail" rather than succeed.

Real rates fall when central banks

back away from stimulus presumably because they "think" they

have done enough and the (global) economy is on a healing

trajectory.

This could be viewed as a damning indictment of policy and is

not unrelated to other structural factors that make policy less

effective than it would be otherwise - including the

self evident break in bank multipliers due to new regulations

and capital requirements.

What would happen then?

Well, DB casually tosses an S&P trading

a "half its value", but more importantly, also remarks that what we

have also said from day one, namely that "helicopter

money" in whatever fiscal stimulus form it takes (even if

it is in the purest literal one) is the only remaining outcome after

a 50% crash in the S&P:

Of course our definition of

"failure" may also be a little zealous. After all

why should equities always rise

in value? Why should debt holders be expected to afford their

debt burden?

There are plenty of alternative

viable equilibria with SPX half its value,

longevity liabilities in default and debt deflation in

abundance.

In those equilibria traditional QE ceases to work

and the only road back to what we think is the current desired

equilibrium is via true helicopter money via fiscal stimulus

where there are no independent central banks.

And there it is: Deutsche Bank saying,

in not so many words, what Ray Dalio hinted at, namely that

the FED's tightening would be the mechanistic precursor to a market

crash and thus, QE4.

Only Deutsche takes the answer to its

rhetorical question if the FED is preparing for a "controlled

demolition" of risk assets one step forward: realizing that at this

point more QE will be self-defeating, the only remaining recourse to

avoid what may be another systemic catastrophe would be the one both

Friedman and Bernanke

hinted at many years ago:

the literal para-dropping of money

to preserve the fiat system for just a few more days (At this

point we urge rereading footnote 18 in Ben Bernanke's

"Deflation

- Making Sure 'It' Doesn't Happen Here" speech)

While we can only note that the gravity

of the above admission by Europe's largest bank can not be

exaggerated - for "very serious banks" to say this, something epic

must be just over the horizon - we should add:

if Deutsche Bank (with

its €55 trillion in derivatives) is right and if the FED

refuses to change its posture,

exposure to any asset which has counterparty risk and/or whose

value is a function of faith in central banks, should be

effectively wound down.

***

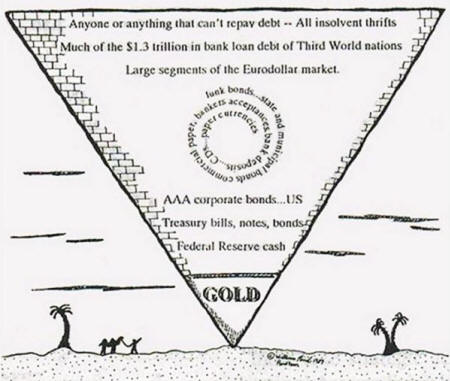

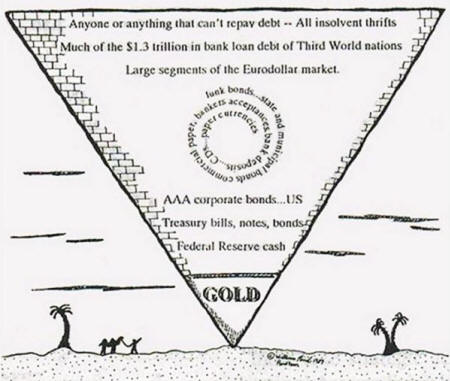

While we have no way of knowing how this

all plays out, especially if Deutsche is correct, we'll leave

readers with one of our favorite diagrams: Exter's inverted pyramid.

|