The top one percent of the wealthiest

people on the planet own nearly fifty percent of the

world's assets while the bottom fifty percent of the

global population combined own less than one percent of

the world's wealth.

"These figures give more evidence

that inequality is extreme and growing, and that

economic recovery following the financial crisis has

been skewed in favor of the wealthiest.

In poor

countries, rising inequality means the difference

between children getting the chance to go to school

and sick people getting life saving medicines."

Emma Seery, Oxfam International

Those are the findings of an annual

report (Global

Wealth Report 2014) by the investment firm Credit Suisse released

Tuesday,

which shows that global economic inequality has surged

since the

financial collapse of 2008.

According to the report,

"global wealth has grown to a new

record, rising by $20.1 trillion between mid-2013

and mid-2014, an increase of 8.3%, to reach $263

trillion - more than twice the $117 trillion

recorded for the year 2000."

Though the rate of this wealth creation

has been particularly fast over the last year - the

fastest annual growth recorded since the pre-crisis year

of 2007 - the report notes that the benefits of this

overall growth have flowed disproportionately to the

already wealthy.

And the report reveals that as of

mid-2014,

"the bottom half of the global

population own less than 1% of total wealth. In

sharp contrast, the richest

decile hold 87% of

the world's wealth, and the top percentile alone

account for 48.2% of global assets."

Campaigners at Oxfam International, which

earlier this put out their

own

report on global inequality, said the Credit

Suisse report, though generally serving separate aims,

confirms what they also found in terms of global

inequality.

"These figures give more evidence

that inequality is extreme and growing, and that

economic recovery following the financial crisis has

been skewed in favor of the wealthiest.

In poor

countries, rising inequality means the difference

between children getting the chance to go to school

and sick people getting life saving medicines,"

Oxfam's head of inequality Emma Seery, told the

Guardian in response to the latest study.

In addition to giving an overall view of

trends in global wealth, the authors of the Credit

Suisse gave special attention to the issue of

inequality in this year's report, noting the increasing

level of concern surrounding the topic.

"The changing distribution of wealth

is now one of the most widely discussed and

controversial of topics," they write.

"Not least owing to [French

economist] Thomas Piketty's recent account of

long-term trends around inequality. We are confident

that the depth of our data will make a valuable

contribution to the inequality debate."

According to the report:

In almost all countries, the mean

wealth of the top decile (i.e. the wealthiest 10% of

adults) is more than ten times median wealth.

For the top percentile (i.e. the

wealthiest 1% of adults), mean wealth exceeds 100

times the median wealth in many countries and can

approach 1000 times the median in the most unequal

nations.

This has been the case throughout

most of human history, with wealth ownership often

equating with land holdings, and wealth more often

acquired via inheritance or conquest rather than

talent or hard work.

However, a combination of factors

caused wealth inequality to trend downwards in high

income countries during much of the 20th century,

suggesting that a new era had emerged.

That downward trend now appears to

have stalled, and possibly gone into reverse.

Working for The Few

Political Capture and Economic Inequality

OXFAM BRIEFING PAPER - SUMMARY 20

JANUARY 2014

from

Oxfam Website

|

This

paper was written by Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva

and Nick Galasso. Oxfam acknowledges the

assistance of Natalia Alonso, Ana Arendar,

Teresa Cavero, Anna Coryndon, Kimberly

Pfeifer and Max

Lawson in its production.

It is

part of a series of papers written to inform

public debate on development and

humanitarian policy issues.

For further information on the issues raised

in this paper please e-mail

advocacy@oxfaminternational.org

|

Housing for the

wealthier middle classes

rises above the

insecure housing of

a slum community in

Lucknow, India.

Photo: Tom Pietrasik/Oxfam

In November 2013, the World Economic Forum released its

'Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014',1

in which it ranked widening income disparities as the

second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18

months.

Based on those surveyed, inequality is

'impacting social stability within countries and

threatening security on a global scale.' Oxfam shares

its analysis, and wants to see the 2014 World Economic

Forum make the commitments needed to counter the growing

tide of inequality.

Some economic inequality is essential to drive growth

and progress, rewarding those with talent, hard earned

skills, and the ambition to innovate and take

entrepreneurial risks. However, the extreme levels of

wealth concentration occurring today threaten to exclude

hundreds of millions of people from realizing the

benefits of their talents and hard work.

Extreme economic inequality is damaging and worrying for

many reasons: it is morally questionable; it can have

negative impacts on economic growth and poverty

reduction; and it can multiply social problems. It

compounds other inequalities, such as those between

women and men. In many countries, extreme economic

inequality is worrying because of the pernicious impact

that wealth concentrations can have on equal political

representation.

When wealth captures government

policymaking, the rules bend to favor the rich, often to

the detriment of everyone else.

The consequences include the erosion of

democratic governance, the pulling apart of social

cohesion, and the vanishing of equal opportunities for

all.

Unless bold political solutions are instituted to

curb the influence of wealth on politics, governments

will work for the interests of the rich, while economic

and political inequalities continue to rise.

As US Supreme Court Justice Louis

Brandeis famously said,

'We may have democracy, or we may

have wealth concentrated in the hands of the few,

but we cannot have both.'

Oxfam is concerned that, left unchecked,

the effects are potentially immutable, and will lead to

'opportunity capture' - in which the lowest tax rates,

the best education, and the best healthcare are claimed

by the children of the rich.

This creates dynamic and mutually

reinforcing cycles of advantage that are transmitted

across generations.

Given the scale of rising wealth concentrations,

opportunity capture and unequal political representation

are a serious and worrying trend.

For instance:

-

Almost half of the world's wealth

is now owned by just one percent of the

population.2

-

The wealth of the one percent

richest people in the world amounts to $110

trillion.

-

That's 65 times the total wealth

of the bottom half of the world's population.3

-

The bottom half of the world's

population owns the same as the richest 85

people in the world.4

-

Seven out of ten people live in

countries where economic inequality has

increased in the last 30 years.5

-

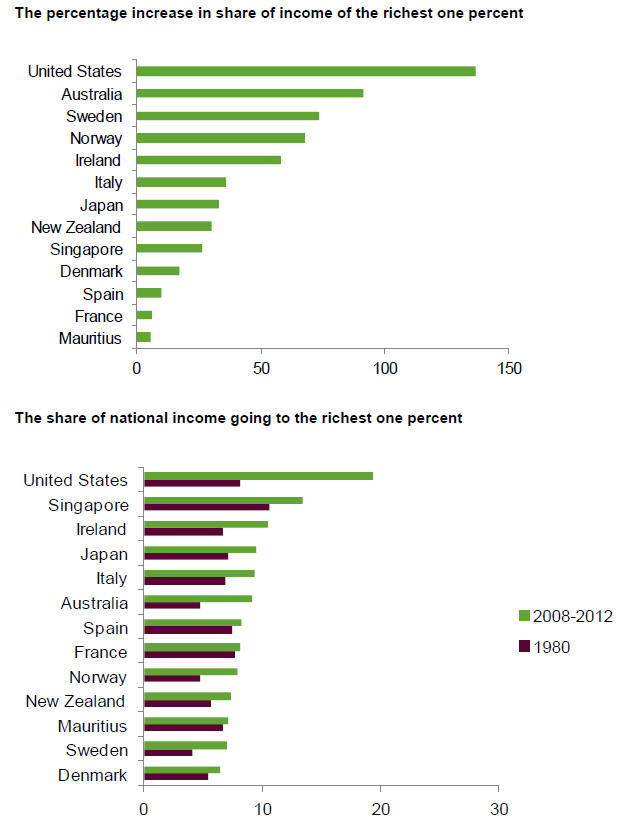

The richest one percent increased

their share of income in 24 out of 26 countries

for which we have data between 1980 and 2012.6

-

In the US, the wealthiest one

percent captured 95 percent of post-financial

crisis growth since 2009, while the bottom 90

percent became poorer.7

This massive concentration of economic

resources in the hands of fewer people presents a

significant threat to inclusive political and economic

systems.

Instead of moving forward together,

people are increasingly separated by economic and

political power, inevitably heightening social tensions

and increasing the risk of societal breakdown.

Oxfam's polling from across the world captures the

belief of many that laws and regulations are now

designed to benefit the rich. A survey in six countries

(Spain, Brazil, India, South Africa, the UK and the US)

showed that a majority of people believe that laws are

skewed in favor of the rich - in Spain eight out of 10

people agreed with this statement.

Another recent Oxfam poll of low-wage

earners in the US reveals that 65 percent believe that

Congress passes laws that predominantly benefit the

wealthy.

The impact of political capture is striking. Rich and

poor countries alike are affected. Financial

deregulation, skewed tax systems and rules facilitating

evasion, austerity economics, policies that

disproportionately harm women, and captured oil and

mineral revenues are all examples given in this paper.

The short cases included are each

intended to offer a sense of how political capture

produces ill-gotten wealth, which perpetuates economic

inequality.

This dangerous trend can be reversed.

The good news is that there are clear

examples of success, both historical and current. The US

and Europe in the three decades after World War II

reduced inequality while growing prosperous.

Latin America has significantly reduced

inequality in the last decade - through more progressive

taxation, public services, social protection and decent

work. Central to this progress has been popular politics

that represent the majority, instead of being captured

by a tiny minority.

This has benefited all, both rich and

poor.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Those gathered at Davos for the

World Economic Forum

have the power to turn around the rapid increase in

inequality.

Oxfam is calling on them to pledge that they

will:

-

Not dodge taxes in their own

countries or in countries where they invest and

operate, by using tax havens;

-

Not use their economic wealth to

seek political favors that undermine the

democratic will of their fellow citizens;

-

Make public all the investments

in companies and trusts for which they are the

ultimate beneficial owners;

-

Support progressive taxation on

wealth and income;

-

Challenge governments to use

their tax revenue to provide universal

healthcare, education and social protection for

citizens;

-

Demand a living wage in all the

companies they own or control;

-

Challenge other economic elites

to join them in these pledges.

Oxfam has recommended policies in

multiple contexts to strengthen the political

representation of the poor and middle classes to achieve

greater equity.

These policies include:

-

A global goal to end extreme

economic inequality in every country. This

should be a major element of the post-2015

framework, including consistent monitoring in

every country of the share of wealth going to

the richest one percent.

-

Stronger regulation of markets to

promote sustainable and equitable growth; and

-

Curbing the power of the rich to

influence political processes and policies that

best suit their interests.

The particular combination of policies

required to reverse rising economic inequalities should

be tailored to each national context.

But developing and developed countries

that have successfully reduced economic inequality

provide some suggested starting points, notably:

-

Cracking down on financial

secrecy and tax dodging

-

Redistributive transfers; and

strengthening of social protection schemes

-

Investment in universal access to

healthcare and education

-

Progressive taxation

-

Strengthening wage floors and

worker rights

-

Removing the barriers to equal

rights and opportunities for women

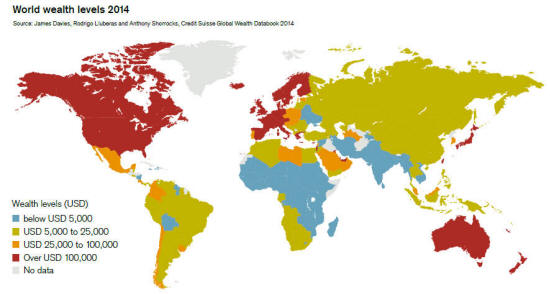

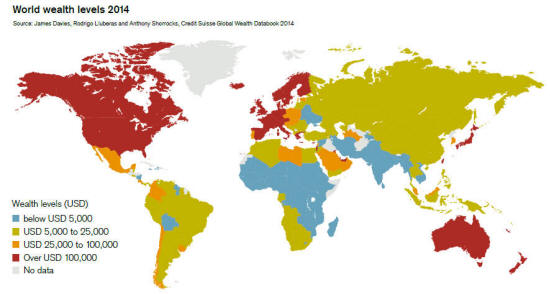

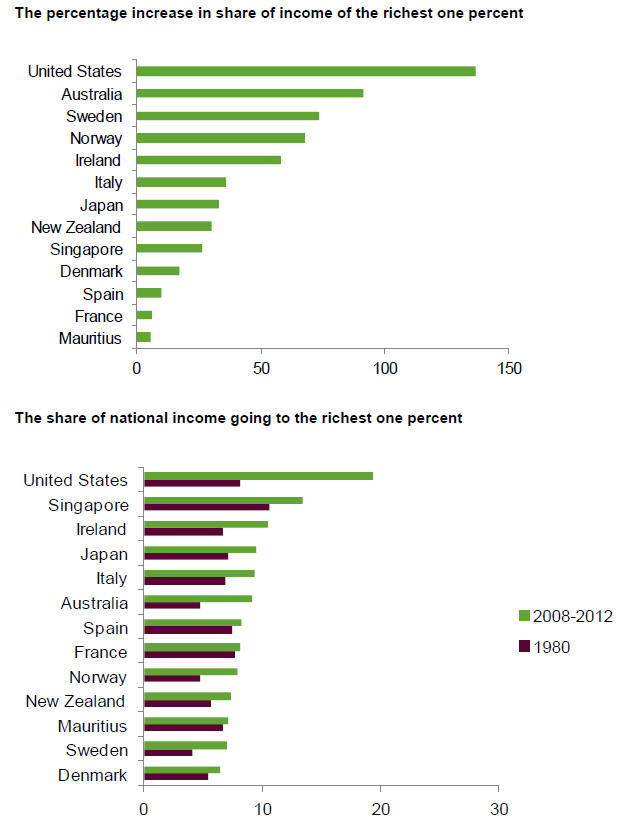

Figure 1: The rich get

richer

Source: F. Alvaredo, A. B. Atkinson, T. Piketty and E.

Saez, (2013)

'The

World Top Incomes Database'

NOTES

-

World Economic Forum (2013)

'Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014', Geneva:

World Economic Forum,

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GAC_GlobalAgendaOutlook_2014.pdf

-

Credit Suisse (2013) 'Global

Wealth Report 2013', Zurich: Credit Suisse.

https://publications.credit-suisse.com/tasks/render/file/?fileID=BCDB1364-A105-0560-1332EC9100FF5C83,

and Forbes' The World's Billionaires (accessed

on December 16, 2013)

http://www.forbes.com/billionaires/list/

-

Calculated based on information

from Credit Suisse, op. cit. Total wealth

amounts to $240.8 trillion. Share of wealth for

the bottom half of the population is 0.71

percent. That for the richest one percent is 46

percent (amounting to $110 trillion).

-

Credit Suisse, op. cit.

-

The World Top Incomes Database,

http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/

-

Ibid.

-

E. Saez (2013) 'Striking it

Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the

United States (updated with 2012 preliminary

estimates)', Berkeley: University of California,

Department of Economics.

http://elsa.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2012.pdf

and The World Top Incomes Database

http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/

OXFAM

Oxfam GB, Oxfam House, John Smith

Drive, Cowley, Oxford, OX4 2JY, UK.

Oxfam is an international confederation of 17

organizations networked together in more than 90

countries, as part of a global movement for change, to

build a future free from the injustice of poverty: