|

from Slate Website

I'm not sure, but I think President Bush just admitted that when somebody briefs him, he consciously prefers what he wants to hear to what the truth happens to be.

As do we all, I suppose. But I see no evidence of irony, let alone self-criticism, in what Bush said. The subject was the National Intelligence Estimate on Iran, from which, as Slate's Fred Kaplan noted yesterday, Bush has been distancing himself in private conversations with foreign leaders.

Here's what Bush said today:

Note that Bush didn't say the intelligence services sometimes come to conclusions separate from what he may or may not believe. It would be bad form for Bush to say that out loud, because it would undermine part of his own executive branch. But it would be defensible intellectually. Of course presidents are going to disagree now and then with conclusions reached by the intelligence agencies.

One would hope that, in doing so, they give careful consideration to the known facts. But Bush wasn't saying that. He was saying that the intelligence services sometimes come to conclusions separate from what he may or may not want. In affirming this, he seemed totally unself-conscious.

There is absolutely no evidence that Bush was describing the necessary mental challenge of rising above what he wants to hear so that he can take in new information that might alter his understanding of reality.

Indeed, Bush's statement suggested that he suffers from a sort of executive learning disability that leaves him unwilling or unable even to grasp that what he wants to hear isn't always going to be the same thing as what he needs to hear.

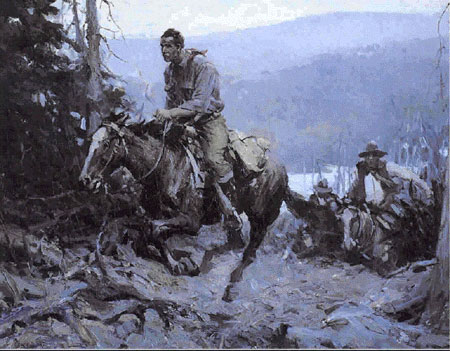

W.H.D. Koerner's A Charge To Keep

Weisberg writes:

As Bush noted in the memo, which he quoted in his autobiography of the same title:

Bush identified with the lead rider, whom he took to be a

kind of Christian cowboy, an embodiment of indomitable vigor, courage, and

moral clarity.

The painting was subsequently recycled by the Saturday Evening Post to illustrate a nonfiction story.

The caption that time was,

Koerner published the illustration a third and final time in a magazine called the Country Gentleman. On this go-round, it was indeed used to illustrate a short story that related to Wesley's hymn. But the story's moral was a little off-message.

According to Weisberg, it was,

Apparently nobody ever got around

to notifying Bush's Interior Department.

I propose that we outfit the Oval Office with a pinball

machine.

Lately, we've been hearing that they should. In the March 13 Washington Post, E.J. Dionne Jr. calls for "a moratorium on calling the president of the United States stupid."

In the March 7 Washington Post, Michael Kelly called Bush a "smart guy." But where is the evidence for this hidden intelligence? Dionne says that Bush has proved himself smart by conning most reporters into thinking he's a moderate. (In fact, Bush is a moderate as "moderate" is currently defined within an extremely conservative national Republican party.)

Kelly says that Bush's respect for his core

conservative constituency's few nonnegotiable issues is smart because it

leaves Bush room to compromise on many other issues that matter to swing

voters. This is something every elected official must do, yet Kelly would

never argue that every elected official is smart.

Borrowing from Bush's own rap on education standards, Bob Herbert of the New York Times has pegged this "the soft bigotry of low expectations."

Ronald Reagan benefited

from a similar bigotry, most memorably when he presented his addled and

self-contradictory explanation for his role in the Iran-Contra scandal. The

"I'm out to lunch" defense was not available to Bill Clinton when he

explained his role in the Marc Rich pardon because the public knows that

Clinton is not a stupid man. Nor was it available to another obviously smart

man, Richard Nixon, during Watergate.

But if the president

really is dumb, don't journalists have a responsibility to say so, even if

their readers don't want to hear it?

David Sanger of the New York Times spotlighted an excellent recent example in a March 8 story about Bush's talks with South Korean president Kim Dae Jung:

If that doesn't persuade you, check out this transcript of Bush's first press conference, where Bush in effect accused a reporter of playing "gotcha" when he was simply trying to find out Bush's stance toward a proposed European rapid-reaction force:

The following day, when Bush was asked the same question again, it was clear

that Bush's answer - the force would defer to NATO and would probably inspire

European nations to increase their defense budgets - needn't have depended on

any special briefing from Blair. Bush had simply been unfamiliar with the

subject.

After all, nobody ever bothered to argue that Jimmy Carter or John F. Kennedy wasn't dumb. Historians have argued, persuasively, that Dwight D. Eisenhower wasn't dumb, but this is something liberal intellectuals should have understood at the time. (How could a dummy have survived as Supreme Allied Commander during World War II?)

More typically, when David Broder and Bob Woodward of the Washington Post published a series (later a book) arguing that Dan Quayle wasn't quite as dumb as people said he was, it could be taken as confirmation that Quayle really was dumb. No politician is as dumb, or as smart, as the public believes him to be because the public lacks the means to acquire a nuanced familiarity with his mind.

But the public can usually form an opinion that's in the ballpark. As Franklin Foer points out in the March 19 New Republic, the much-maligned "conventional wisdom," though banal, is usually correct. Lately there's been a lot of revisionist thinking about Ronald Reagan's grasp of policy nuance based on a cache of recently unearthed radio commentaries and speeches.

These have been published in a book, Reagan In His Own Hand, which is being lauded by conservatives. What Chatterbox sees when he gazes into Reagan In His Own Hand, though, is the condescension of editor Martin Anderson, a longtime Reagan adviser, and of George Shultz, who wrote the foreword.

Here's Shultz:

In his introduction, Anderson and his co-editors marvel that Reagan's radio

broadcasts

drew upon hundreds of sources, and his drafts contain thousands of facts and

figures. Sometimes he lists his sources in accompanying documents. In one

case, for an essay on oil, he appended them. At times he cites his sources

in the text.

If Shultz and Anderson said these things about you, would you really feel flattered?

Or would you want to punch them in the nose?

Video

George W. Bush - American Idiot

|