|

from WorldPoliticsReview Website

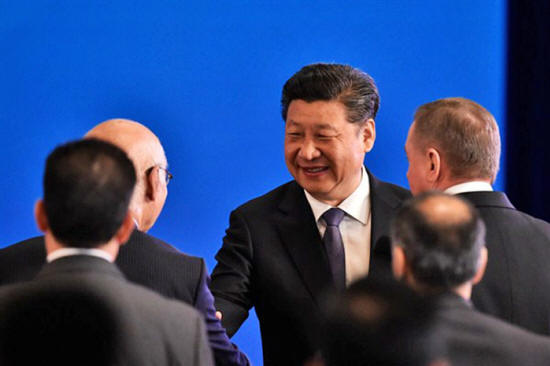

Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia, Beijing, April 28, 2016 (AP pool photo)

Under President Donald Trump, the U.S. appears

to be distancing itself from its established role as leader of the

global system. Many excitable pundits and even sober diplomats have

speculated that Beijing could fill the vacuum America is creating. I have to confess to being one of the excitable ones.

I argued in December that Chinese President Xi Jinping could counter Trump,

At the time, Trump - then the president-elect - threatened to punish the United Nations for a Security Council resolution on Israel.

It was asserted that,

This wasn't just armchair speculation.

In the aftermath of the U.S. election, Chinese officials made it plain that they wanted the new administration in Washington to stand by the Paris climate change treaty.

In January,

Xi stole headlines with a

pointed speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos lauding

globalization and free trade.

Beijing is

sending representatives to talks with other Pacific nations in Chile

this week to discuss

what can be salvaged from the Trans-Pacific Partnership

(TPP), the

Obama administration's flagship trade agreement that Trump abandoned

in one of his first official acts as president.

China is liable to takea more transactionalthan transformational approachto international institutions,looking to strike specific bargainsrather than take the lead.

But while these diplomatic maneuvers send the message that China remains a solid partner in an uncertain world, Beijing has yet to make a serious play to supplant the U.S. as a global leader.

China's immediate priorities appear to have been persuading Trump to stand by the One China policy regarding Taiwan and to ease mounting tensions on the Korean peninsula.

It has very publicly suspended coal imports from North Korea to comply with U.N. sanctions.

China currently looks more like a status quo power

focused on regional security rather than a revisionist power with

aspirations to global leadership.

Godemont argues that, while China has benefited from liberal international institutions and globalization, it does not necessarily have a cohesive vision of these.

To simplify the argument, the U.S. and other Western counterparts tend to see the sprawling international system that has evolved since 1945 as some sort of package.

If you like breaking down trade

barriers, you should also believe in limits to sovereign states'

right to suppress their citizens. If you think that the U.N. should

invest in global development, to get more technical, you should also

prize its human rights work.

It is also keen on, and good at, securing more senior positions in international secretariats for its nationals.

But Chinese officials also see many dimensions of the liberal order as irrelevant or actively antagonistic to their interests.

They have

not offered any serious funds to U.N. humanitarian efforts to

ease the global refugee crisis, which has little direct impact on

China, and consistently oppose U.N. bodies' efforts to promote

liberal human rights norms.

China became the second-biggest contributor to the $8 billion peacekeeping budget in 2016, and its diplomats are evidently proud of this. The fact that Beijing relegated Japan to third place in the process probably helps.

But the newly emboldened Chinese delegation in Turtle Bay

took a destructive approach to their new status in budget talks last

year, demanding big cuts to the human rights components of U.N.

blue-helmet missions, as well as to the staff dealing with sexual

abuses by peacekeepers.

Chinese analysts often frame this relatively cautious approach as the "democratization" of international organizations, or a search for "harmony" within them.

This sort of language may

obscure Beijing's specific diplomatic goals, but many Asian and

African officials much prefer it to Western hectoring about liberal

values.

Instead, the global system will evolve through friction,

barter and compromise.

The problem is that the West may have reached that point already.

|