by Tyler Durden

March 09, 2014

from

ZeroHedge Website

While the US may be rejoicing its daily stock

market all time highs day after day, it may come as a surprise to many that

global equity capitalization has hardly performed as impressively compared

to its previous records set in mid-2007.

In fact, between the last bubble peak, and

mid-2013, there has been a $3.86 trillion decline in the value of equities

to $53.8 trillion over this six year time period, according to data compiled

by Bloomberg.

Alas, in a world in which there is no longer

even hope for growth without massive debt expansion, there is a cost to

keeping global equities stable (and US stocks at record highs):

that cost is $30 trillion, or nearly double

the GDP of the United States, which is by how much global debt has risen

over the same period.

Specifically,

total global debt has exploded by 40% in just 6 short years from 2007 to

2013, from "only" $70 trillion to over $100 trillion as of mid-2013,

according to the

BIS' just-released quarterly review.

It should come as no surprise to anyone by now,

but the only reason why global stocks haven't plummeted since the Lehman

collapse is simple:

governments have become the final backstop

for onboarding risk, with a Central Bank stamp of approval - in other

words, the very framework of the fiat system is at stake should global

equity levels collapse.

The BIS admits as much:

“Given the

significant expansion in government spending in recent years,

governments (including central, state and local governments) have been

the largest debt issuers,” according to Branimir Gruic, an

analyst, and Andreas Schrimpf, an economist at the BIS.

It should also come as no surprise that courtesy

of ZIRP and monetization of debt by every central bank, debt has itself

become money regardless of duration or maturity (although recent taper

tantrums have shown what will happen once rates start rising across the

curve again), explaining the mind-blowing tsunami of new debt issuance,

which will certainly never be repaid, and whose rolling will become

impossible once interest rates rise.

But of course, under central planning that is

not allowed.

As

Bloomberg reminds us, marketable U.S. government debt outstanding has

surged to a record $12 trillion, up from $4.5 trillion at the end of

2007, according to U.S. Treasury data compiled by Bloomberg.

Corporate

bond sales globally jumped during the period, with issuance totaling more

than $21 trillion, Bloomberg data show.

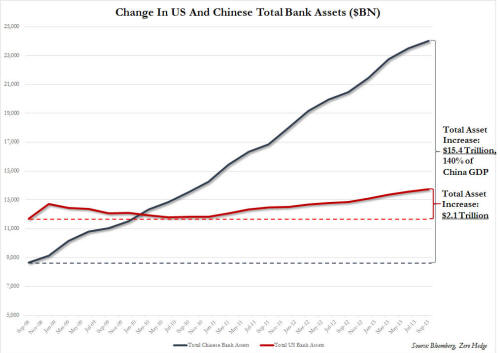

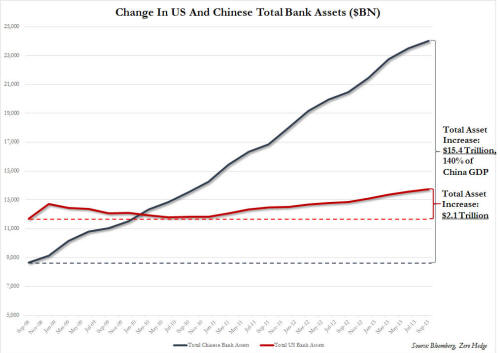

And as we won't tire of pointing out, China's

credit expansion over this period is easily the most important, and

overlooked one. Which is why with China out of the epic debt issuance

picture, and with

the FED tapering, all bets are slowly

coming off.

Bloomberg also comments, humorously, as follows:

"concerned that high debt loads would cause

international investors to avoid their markets, many nations resorted to

austerity measures of reduced spending and increased taxes, reining in

their economies in the process as they tried to restore the fiscal order

they abandoned to fight the worldwide recession."

Of course, once gross government corruption and

incompetence made all attempts at austerity futile, and with even the

austere nations' debt levels continuing to

breach record highs confirming there was never any actual austerity to begin

with, the push to pretend to reign debt in has finally faded, and

the entire world is once again engaged - at breakneck speed - in doing what

caused the great financial crisis in the first place: the issuance of record

amounts of unsustainable debt.

All of the above is known. What may not be known

is just who is issuing, and respectively, purchasing, this global

debt-funded spending spree, especially in a world in which one's debt is

another's asset.

Here is

the BIS's answer to that question:

Cross-border

investments in global debt markets since the crisis

Branimir Gruic and Andreas Schrimpf

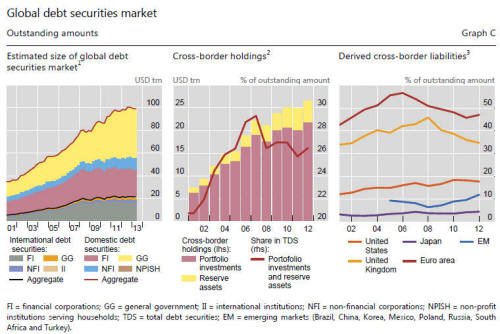

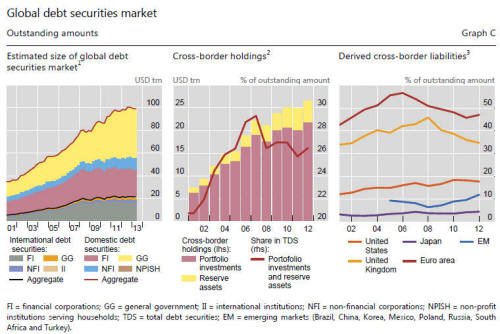

Global debt markets have grown to an estimated $100 trillion (in amounts

outstanding) in mid-2013 (Graph C, left-hand panel), up from $70

trillion in mid-2007. Growth has been

uneven across the main market segments.

Active issuance by governments and

non-financial corporations has lifted the share of domestically issued

bonds, whereas more restrained activity by financial institutions has

held back international issuance (Graph C, left-hand panel).

Not surprisingly, given the significant

expansion in government spending in recent years, governments (including

central, state and local governments) have been the largest debt issuers

(Graph C, left-hand panel).

They mostly issue debt in domestic markets,

where amounts outstanding reached $43 trillion in June 2013, about 80%

higher than in mid-2007 (as indicated by the yellow area in Graph C,

left-hand panel). Debt issuance by non-financial corporates has grown at

a similar rate (albeit from a lower base).

As with governments, non-financial

corporations primarily issue domestically. As a result, amounts

outstanding of non-financial corporate debt in domestic markets

surpassed $10 trillion in mid-2013 (blue area in Graph C, left-hand

panel).

The substitution of traditional bank loans

with bond financing may have played a role, as did investors’ appetite

for assets offering a pickup to the ultra-low yields in major sovereign

bond markets.

Financial sector deleveraging in the

aftermath of the financial crisis has been a primary reason for the

sluggish growth of international compared to domestic debt markets.

Financials (mostly banks and non-bank

financial corporations) have traditionally been the most significant

issuers in international debt markets (grey area in Graph C, left-hand

panel). That said, the amount of debt placed by financials in the

international market has grown by merely 19% since mid-2007, and the

outstanding amounts in domestic markets have even edged down by 5% since

end-2007.

Who are the investors that have

absorbed the vast amount of newly issued debt? Has the investor base

been mostly domestic or have cross-border investments grown at a similar

pace to global debt markets?

To provide a perspective, we combine

data from the BIS securities statistics with those of the IMF

Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS).

The results of the CPIS

suggest that non-resident investors held around $27 trillion of global

debt securities, either as reserve assets or in the form of portfolio

investments (Graph C, centre panel).

Investments in debt securities by non-residents thus accounted for

roughly one quarter of the stock of global debt securities, with

domestic investors accounting for the remaining 75%.

The global financial crisis has left a

dent in cross-border portfolio investments in global debt securities.

The share of debt securities held by cross-border investors either as

reserve assets or via portfolio investments (as a percentage of total

global debt securities markets) fell from around 29% in early 2007 to

26% in late 2012.

This reversed the trend in the

pre-crisis period, when it had risen by 8 percentage points from 2001 to

a peak in 2007.

It suggests that the process of international financial integration may

have gone partly into reverse since the onset of the crisis, which is

consistent with other recent findings in the literature.

This could be temporary, though. The latest

IMF-CPIS data indicate that cross-border investments in debt securities

recovered slightly in the second half of 2012, the most recent period

for which data are available.

The contraction in the share of cross-border

holdings differed across countries and regions (Graph C, right-hand

panel).

Cross-border holdings of debt issued by euro

area residents stood at 47% of total outstanding amounts in late 2012,

10 percentage points lower than at the peak in 2006. A similar trend can

be observed for the United Kingdom.

This suggests that the majority of new debt

issued by euro area and UK residents has been absorbed by domestic

investors. Newly issued US debt securities, by contrast, were

increasingly held by cross-border investors (Graph C, right-hand panel).

The same is true for debt securities issued by borrowers from emerging

market economies.

The share of emerging market debt securities

held by cross-border investors picked up to 12% in 2012, roughly twice

as high as in 2008.

Source:

BIS Quarterly Review March 2014 - International

banking and financial market developments