by Jon

Hilsenrath and

Brian Blackstone

December 12, 2012

from WallStreetJournal Website

|

A version of this article

appeared December 12, 2012, on page A1 in the U.S. edition of The

Wall Street Journal, with the headline:

Inside the Risky Bets of

Central Banks. |

BASEL, Switzerland

Every two months, more than a dozen bankers meet

here on Sunday evenings to talk and dine on the 18th floor of a cylindrical

building looking out on the Rhine.

The dinner discussions on money and economics are more than academic.

At the

table are the chiefs of the world's biggest central banks, representing

countries that annually produce more than $51 trillion of gross domestic

product, three-quarters of the world's economic output.

Central Banks Making Risky Bets on Global Economy

The world's major central banks are embarking on an aggressive new phase

of

policy activism, a course fraught with economic and political risks.

WSJ's

Jon Hilsenrath reports on the News Hub.

Of late, these secret talks have focused on global economic troubles and the

aggressive measures by central banks to manage their national economies.

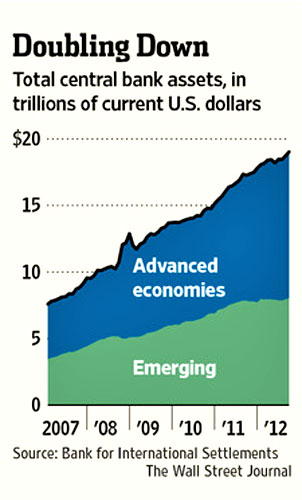

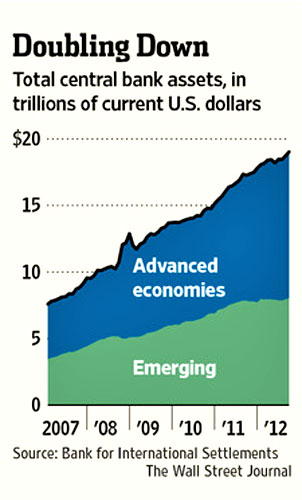

Since 2007, central banks have flooded the world financial system with more

than $11 trillion. Faced with weak recoveries and Europe's churning economic

problems, the effort has accelerated. The biggest central banks plan to pump

billions more into government bonds, mortgages and business loans.

Their monetary strategy isn't found in standard textbooks.

The central

bankers are, in effect, conducting a high-stakes experiment, drawing in part

on academic work by some of the men who studied and taught at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1970s and 1980s.

While many national governments, including the U.S., have failed to agree on

fiscal policy - how best to balance tax revenues with spending during slow

growth - the central bankers have forged their own path, independent of voters

and politicians, bound by frequent conversations and relationships

stretching back to university days.

If the central bankers are correct, they will help the world economy avoid

prolonged stagnation and a repeat of central banking mistakes in the 1930s.

If they are wrong, they could kindle inflation or sow the seeds of another

financial crisis.

Failure also could lead to new restrictions on the power

and independence of central banks, tools deemed crucial in such emergencies

as the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

"Will history decide they did too little or too much? We don't know because

it is still a work in progress," said Kenneth Rogoff, an economics professor

at Harvard and co-author of a book.

"This Time Is Different," examining

financial crises over eight centuries. "They are taking risks because it is

an experimental strategy."

-

The

U.S. Federal Reserve now buys $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities

each month and appears set at a meeting Wednesday to spend billions more on

Treasury securities.

-

The Bank of England has agreed to funnel billions of

pounds to businesses and households through banks.

-

The European Central Bank

pledged to hold down borrowing costs of governments that sought help.

-

The

Bank of Japan, under increased pressure to fight deflation,

is purchasing ¥91 trillion yen ($1.14 trillion) in government bonds,

corporate debt and stocks.

The goal is to lower borrowing costs and stimulate stock markets to

encourage spending and investment by households and business. But the method

is untested on such a global scale, and central bankers have labored in

behind-the-scenes meetings this year to size up the risks.

A day after their June dinner here, the central bankers were warned by one

of their hosts in a speech to the group.

"Central banks find themselves caught in the middle, forced to be the policy

makers of last resort. They are providing monetary stimulus on a massive

scale," said Jaime Caruana, general manager of the Bank for International

Settlements, where the dinners are held.

"These emergency measures could

have undesirable effects if continued for too long."

Another worry:

Boosting stock markets and easing credit costs allow national

governments to postpone difficult political decisions to fix such problems

as swelling budget deficits, according to this contrary view.

Vocal critics include economists at the BIS, an international body based

here that is increasingly an important staging ground for talks about the

postcrisis financial landscape.

They say central banks, seeking faster

growth, are stretched too thin.

"Central banks cannot solve structural problems in the economy," said

Stephen Cecchetti, who runs the BIS monetary department. "We've been saying

this for years, and it's getting tiresome."

Central banks control the spigot of the world's money supply.

When opened,

the flow of new cash heats up economies, driving down interest rates and

unemployment but risking inflation. Closing the spigot, on the other hand,

raises interest rates and cools economies but tamps down prices.

The central bankers have promised that once the global economy gets back on

its feet, they will shut off the spigots quickly enough to forestall

inflation.

But pulling back so much money, at exactly the right time, could

become a political and logistical challenge.

"We're all very conscious that we're in an environment that's unusual and

we're using a policy weapon that we don't have a lot of experience with,"

Charles Bean, deputy governor of the Bank of England said in an interview.

Central bankers themselves are among the most isolated people in government.

If they confer too closely with private bankers, they risk unsettling

markets or giving traders an unfair advantage.

And to maintain their

independence, they try to keep politicians at a distance.

Since the financial crisis erupted in late 2007, they have relied on each

other for counsel. Together, they helped arrest the downward spiral of the

world economy, pushing down interest rates to historic lows while pumping

trillions of dollars, euros, pounds and yen into ailing banks and markets.

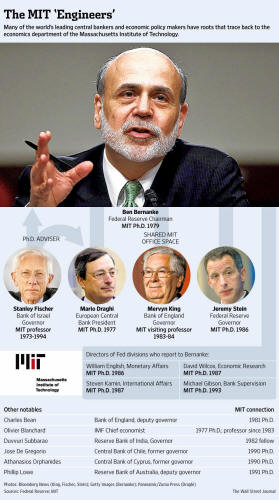

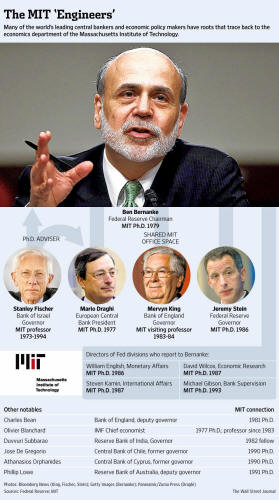

Three of the world's most powerful central bankers launched their careers in

a building known as "E52," home to the MIT economics department.

-

Fed

Chairman Ben Bernanke and ECB President Mario Draghi earned their Ph.D.s

there in the late 1970s.

-

Bank of England Governor Mervyn King taught briefly

there in the 1980s, sharing an office with Mr. Bernanke.

Many economists emerged from MIT with a belief that government could help to

smooth out economic downturns.

Central banks play a particularly important

role in this view, not only by setting interest rates but also by

influencing public expectations through carefully worded statements.

While at MIT, the central bankers dreamed up mathematical models and

discussed their ideas in seminar rooms and at cheap food joints in a rundown

Boston-area neighborhood on the Charles River.

Over Sunday dinners in Basel, which often stretch to three hours, they now

talk of pressing, real-world problems with authority. The meals are part of

two-day meetings held six times a year at

the BIS.

Dinner guests include

leaders of,

-

the Fed

-

ECB

-

Bank of England

-

Bank of Japan,

...as well as

central bankers from,

-

India

-

China

-

Mexico

-

Brazil,

...and a few other countries.

"That is where it really gets down and dirty," said Nathan Sheets, a

Citigroup C -0.70% economist and former head of the Federal Reserve's

international affairs division.

He didn't attend the dinners during his

tenure at the Fed but is familiar with them.

"Every one of the dinners was

important through the crisis."

The Bank of England's Mr. King leads the dinner discussions in a room

decorated by the Swiss architectural firm Herzog & de Meuron, which designed

the "Bird's Nest" stadium for the Beijing Olympics.

The men have designated

seats at a round table in a dining area scented by white orchids and framed

by white walls, a black ceiling and panoramic views.

"It is a way in which people can talk completely privately," Mr. King said

in an interview. "It is a big advantage if you have some feel for how

central banks think about questions, what they're likely to do in the future

if certain events were to occur."

Serious matters follow appetizers, wine and small talk, according to people

familiar with the dinners.

Mr. King typically asks his colleagues to talk

about the outlook in their respective countries. Others ask follow-up

questions. The gatherings yield no transcripts or minutes. No staff is

allowed.

The 18-member group, formally known as the Economic Consultative Committee,

has only once issued a public statement:

a two-line missive in September,

promising to look for solutions in interbank lending markets, responding to

allegations that some private banks had conspired to manipulate the Libor

interest rate.

On Mondays after the dinner, the bankers join a larger group of central

bankers at a large round table on a lower floor of the BIS building, which

is shaped like a rook chess piece.

Staff members sit nearby at desks

decorated in white leather.

"These meetings are a very important forum to understand the global

situation," said Duvvuri Subbarao, governor of the Reserve Bank of India and

a Sunday dinner participant. "People speak freely."

The central bankers often act with the common goal of bringing the world

closer to full employment.

Other times, though, they are starkly at odds.

In November 2010, for example, the Fed launched a $600 billion bond-buying

program known as quantitative easing. A few days later, New York Fed

President William Dudley and Fed vice chairwoman Janet Yellen attended a

weekend meeting here and were surprised by the furor the Fed's stimulus

program had stirred among developing countries, according to people familiar

with the talks.

Mr. Dudley and Ms. Yellen spent much of the meeting

explaining the Fed's actions, as other central bankers raised worries the

program would cause inflation or spark an unwanted flood of capital into

their markets.

"Every time there is quantitative easing by the Fed, that gets discussed,"

said Mr. Subbarao. "We all have to reckon with the spillover impact of our

policies on other countries."

Basel, he said, is the place to air such

concerns.

The role of the Bank for International Settlements has broadened since it

was formed in 1930 to handle reparation payments imposed on Germany after

World War I. In the 1970s, it became the center of discussions on bank

capital rules. In the 1990s, it became the meeting place for central bankers

to talk about the global economy.

The central bankers typically stop short of formally coordinating their

moves. Mr. Bernanke, Mr. Draghi and Bank of Japan head Masaaki Shirakawa are

more focused on domestic challenges.

Mr. Shirakawa has often warned others

in Basel about the effectiveness of easy money policies, according to people

familiar with his statements.

That hesitance has made the BOJ an issue in

Sunday's Japan elections. Shinzo Abe, the front-runner to become prime

minister, has promised to rein in the BOJ's independence and demand more

aggressive efforts to end consumer price deflation.

But as central bankers grapple with doubts and disagreements over reviving

the global economy, they form a tight-knit fraternity, tied by efforts to

manage growth and gird against financial instability.

Their relationships

play out during conversations by phone and in person.

"A big secret of central bank cooperation," Mr. King said, "is that you can

just pick up a phone and have an agreement on something very quickly" in a

crisis.

This summer, the central banking clique kept in close touch as they readied

for a new round of monetary activism.

On June 8, Mr. Bernanke and Mr. King

spoke by phone for a half-hour before policy meetings at their central

banks, according to Mr. Bernanke's phone records, obtained in a public

records request. A few days later, Mr. Bernanke spoke by phone with Mark

Carney, head of the Bank of Canada - and last month named as Mr. King's

successor.

Shortly after, Mr. Bernanke called Stanley Fischer, head of the

Bank of Israel, and a former MIT professor who was Mr. Bernanke's

dissertation adviser.

On June 18, Mr. Bernanke had an early morning call from his home on Capitol

Hill with Mr. Draghi and Mr. King, according to his phone records, as the

men assessed the impact of the Greek election on Europe's financial system.

Two conflicting views tug at the world's central bankers. One view is that

central banks haven't done enough to attack economic malaise. The other is

that easy-money policies lack sufficient power to help economies and risk

triggering runaway inflation or another financial bubble.

In August, tension over the two positions spilled into the open during the

Fed's annual retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyo.

Adam Posen, who recently finished

a four-year term as a member of the Bank of England's monetary policy

committee, chastised central bankers for their unwillingness to do more to

stimulate their economies because of "self-imposed taboos."

Mr. Posen said central banks should give more help to such weakened markets

as U.S. mortgages and European government bonds.

Athanasios Orphanides, another MIT professor who recently finished a term as

the head of the central bank of Cyprus, took the opposing view. In the

1970s, he said, central banks sought to return unemployment to low levels of

the 1960s.

They made the mistake of keeping interest rates too low for too

long, he said, yielding inflation instead of full employment.

If banks

repeat the mistake of overestimating their ability to push unemployment

lower, he said,

"disaster will follow on the price front."

Mr. Bean, meanwhile, said he worried that current low-interest-rate policies

were losing their efficacy, an idea recently echoed by Mr. King.

Low rates,

he said, might induce less-than-expected business and consumer spending when

governments and the private sector are burdened by too much debt.

"There is a lot we don't understand," said Donald Kohn, the Fed's former

vice chairman.

Mr. Bernanke sat quietly during the discussion. But he and the other major

central bankers were already primed to launch a new monetary onslaught.

A few days later, the ECB announced an agreement to buy bonds of struggling

European governments in exchange for a country's adherence to fiscal

austerity.

Then the Fed announced plans to buy bonds every month until U.S. job market

improves "substantially." The BOJ, despite Mr. Shirakawa's hesitance, soon

followed with news it also was expanding its bond-buying program.

Economists at the BIS, meanwhile, have grown more skeptical about the

central bank tilt.

They say their warnings of a credit bubble were ignored

before the financial crisis.

"Nobody took it seriously," said William White,

formerly the top BIS economist.

Now, he said, the central banks may again be steering toward long-term

troubles in their elusive quest for short-term growth.