|

by Fannie Weinstein

The Detroit News

April 21, 1994

from

JohnEMackInstitute Website

|

Fannie Weinstein is a

Detroit News staff writer.

A second article by Fannie Weinstein originally

accompanied this piece but is not reproduced here; it

presented the stories of three experiencers.

“All three,” wrote

Weinstein, “say that before they met Mack, they had

been afraid to tell anyone but their closest

confidants about their encounters because of the

stigma surrounding the abduction controversy.

They're coming forward now, they say, so other

abductees will know they're not alone.”

An additional note: The

main article reproduced below ran under many different

titles in different newspapers (the article having been

syndicated nationwide via the Gannett News Service).

Different papers ran the article in different lengths.

This website had been

running the article under the title “A Close Encounter

with Critics” before it came into possession of the

original newsprint (pictured below), so we are

continuing to run the article under that title even

though it may be more properly recognized as “The Body

Snatchers” now that we are presenting the full text as

originally run in the Detroit News. |

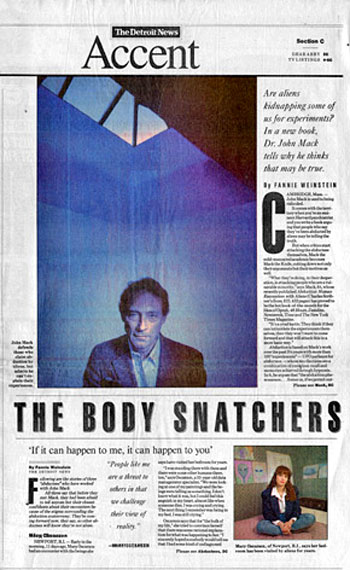

John Mack is used to being

ridiculed.

It comes with the territory when you're an eminent Harvard

psychiatrist and you write a book arguing that people who say

they've been abducted by aliens may be telling the truth.

But when critics start attacking the abductees themselves, Mack the

mild-mannered academic becomes Mack the Knife, cutting down not only

their arguments but their motives as well.

“What they're doing, in their

desperation, is attacking people who are a vulnerable minority,”

says Mack, 64, whose

Abduction - Human Encounter with Aliens

has proved to be the hot book-of-the-month for the likes of

Oprah, 48 Hours, Dateline, Newsweek, Time and The New York Times

Magazine.

“It's a cruel tactic. They think if they can intimidate the

experiencers themselves, then they won't want to come forward

and that will attack this in a more basic way.”

Abduction is based on Mack's work over

the past three and a half years with more than 100 “experiencers” -

UFO parlance for abductees - whose recollections are a combination

of conscious recall and memories achieved through hypnosis. In it,

he argues that,

“the abduction phenomenon... forces

us, if we permit ourselves to take it seriously, to re-examine

our perception of human identity - to look at who we are from a

cosmic perspective.”

Does this mean Mack actually believes

his subjects have been abducted by aliens? Not exactly.

"The word 'believe,' in American

English means suckered in, that somebody sold you a bill

of goods,” he explains. “So I have to qualify that."

“What I say is that these are people who as best as I can tell

have no reason to be distorting this phenomenon, who have

nothing to gain personally, who have come forward reluctantly,

who do not remotely demonstrate a form of mental disturbance

that could account for what they're saying and who, with or

without hypnosis and with intense feeling describe what [sounds

like] real experience.”

“So I say these people are speaking authentically, genuinely and

that it's a mystery I can't explain.”

The opposition

One thing Mack's critics can't dispute are his credentials.

Mack received his medical degree from Harvard in 1955 and has been a

professor of psychiatry at Cambridge Hospital, an affiliate of

Harvard Medical School, since 1972. He has written numerous

critically acclaimed books and is perhaps best known for his 1977

Pulitzer Prize-winning psychoanalytic biography of T.E. Lawrence.

But it's these very credentials, some critics say, that are creating

a smoke screen when it comes to analyses of Mack's work.

“Mack is a rather charismatic

personality, and the fact that he comes from Harvard seems to

give his views more authority,” argues Philip Klass, publisher

of the Skeptics UFO Newsletter.

“It's as if General [Norman]

Schwarzkopf were to make some crazy pronouncement dealing with

defense matters. People would say, 'Gee, he's a military man. He

must know what he's talking about.'”

Especially disturbing to Klass, a

journalist who has written about space technology for more than 40

years, is the lack of what he calls “scientifically credible

evidence” for extraterrestrial life.

“After spending more than a

quarter-century investigating UFO reports, I have yet to find a

single such case.”

Klass is as dismissive of the so-called

“abductees” as he is of Mack.

“They live humdrum lives,” he says.

“Nobody would ask them to appear on a talk show on the basis of

their normal lives. But all they have to do is read a book or

two about abductions, concoct a somewhat similar story and

they're a local celebrity. And who knows? Maybe they can write a

book and become a millionaire.”

It's not just lay persons, though, who

are troubled by Mack's latest direction. Even some of his colleagues

question its validity.

“People respect his other

achievements,” says Dr. Malkah Notman, acting chairwoman of

Cambridge Hospital's psychiatry department [which Mack founded].

“But the perception is that this is not a productive area.”

You'll never convince Mack of that.

A

tall, handsome man with dark hair and graying temples, he talks

about the abduction phenomenon with the kind of enthusiasm usually

limited to eager young professionals.

Outfitted in a blue tweed sports coat, a pale blue button-down shirt

and gray corduroy slacks - looking ever the part of the slightly

disheveled professor - Mack spent much of a recent interview rocking

back and forth in a worn, leather desk chair that takes up a sizable

chunk of his tiny Cambridge Hospital office.

For the most part, Mack is philosophical about the stir his book is

making.

“My work seems to have stimulated a

kind of polarization in the media,” says Mack, who speaks as

much with his hands as with his mouth. “On the one hand, you

have people who are somewhat open. They may be nervous, but

they've allowed themselves to walk through my process and they

see that something's going on here that's mysterious.”

“The other end of the pole is people who simply say this is not

possible. They completely dismiss the association with UFOs,

they completely dismiss the fact that the phenomenon occurs in

children as young as 2 or 3 years old, they completely dismiss

the fact that the experiences are consistent among thousands of

people all over the country and they dismiss the fact that I say

there isn't mental illness here.

Then they become snide, nasty

and personally attack me.”

Intellectual

Challenges

Mack became interested in the abduction phenomenon after a colleague

introduced him to

Budd Hopkins, a New York artist

who is considered the father of the abduction-awareness movement.

At first, Mack says he was as skeptical as the next guy.

The pair met in January 1990, and Hopkins told Mack about people

from all over the country who had told him about their experiences.

A month later, Mack met with four abductees and became intrigued by

the philosophical, spiritual and social implications of what they

had to say.

Most significantly, Mack writes in the book's introduction, the

phenomenon calls into question the basic Western belief that reality

is grounded only in the material world or in what can be perceived

by the physical senses.

It's this intellectual dilemma, Mack says, that explains why people

are so disturbed by the phenomenon.

“We like to believe we are in

control our world,” he says, “that we can bulldoze it, blow up

the enemy.”

“That illusion of control is deeply built into the Western

psyche. This phenomenon strikes at the core of that and says not

only are we not in control, that some kind of intelligence can

break through and do threatening things to people for which

there's no defense, it also shatters another belief - that we an

the preeminent intelligence, if not the only intelligence, in

the cosmos. It makes a mockery of our arrogance.”

'Experiencers'

The most notable characterization of the abductees, says Mack, is

that they can't be categorized. His own sample includes students,

housewives, secretaries, writers, business people, computer industry

professionals and psychologists.

Some of the abductees come from broken homes, others come from

intact, well-functioning families.

Experiencers, say their abduction encounters begin most commonly in

homes and at night. Usually the experiencer is accompanied by one or

two or mom humanoid beings who guide them to a ship. The experiencer

often discovers that he or she is unable to move at will.

Inside the ships the experiencers remember witnessing mom alien

beings. The entities most commonly observed are small, gray humanoid

beings 3 to 4 feet tall. They usually have large, pear-shaped heads

that protrude in the back, long arms with three or four long

fingers, a thin torso and spindly legs.

Abductees are often subjected to procedures in which

instruments are used to penetrate virtually every part of their

bodies, including the nose, sinuses, eyes, ears and other parts of the

head, arms, legs, feet, abdomen, genitalia and more rarely, the

chest.

Sometimes instruments are used to take sperm samples from men and to

remove or fertilize eggs from females. Abductees report being

impregnated by aliens and later having an alien-human or human-human

pregnancy terminated. Also, some report the presence of homing

objects, or implants, that have been inserted in their bodies so

that the aliens can track and monitor them.

Afterwards, many abductees suffer long-term physical symptom such as

headaches, nasal sinus pain, limb pains and gastrointestinal and

urological-gynecological symptom.

Because they often suffer some sort of psychological trauma as well,

Mack tries to ensure that the abductees have access to mental health

professionals if he can't see them himself.

“I try to make sure they have

someone they can talk to who at least understands the

phenomenon,” he says. “One of the things that is really

troubling is that there aren't enough people who are qualified

to do this work. But that's changing. I now have two

psychiatrists in the area who are open to it and who will see

these people.”

The chances of Mack and his critics ever

seeing eye-to-eye is slim.

Take Klass, for example, who confesses

facetiously that he keeps a video camera by his bedside.

“I figure if I am abducted and if I

can get video on board a flying saucer, I could really do very

well,” he cracks.

For his part, Mack is less concerned

with battling his critics than he is with openings public dialogue

about the abduction phenomenon.

“I want people to ask themselves, is

it possible that something they don't understand is going on

here?” he says.

“My role, my responsibility, is to

open a serious conversation in this culture that maybe there are

dimensions and realities and something going on hem that we

don't understand, and that it might be more useful for us to

acknowledge this than to shoot the messengers.”

|