|

translation from Portuguese by Silvio Mattievich Information sent by Enrico Mattievich via Email on May 30, 2020

Chavín de Huantar

hold the key to the hidden significance

of the Greek

myths...

From the palpable reality - the archaeological site of Chavín - an enigma since its discovery - I went to look for in Greek-Roman mythology, in search for an answer.

This paper, excerpted

from my book "Journey

to the Mythological Inferno", discusses the first part of

the archaeological, geographical and documentary evidences, which

favors the possibility that the mysterious remains of Chavín de

Huantar, in the Peruvian Andes, are referred to in Hesiod's

Theogony, a Greek treatise of the gods, written in the eighth

century BC.

The binomial Atlas-Hesperides is quoted in the Theogony - a Greek treatise of the gods - written by Hesiod around the 8th century B.C.

According to this

treatise, next to the Hesperides - which guarded the golden apples -

somewhere in the western limits of the Earth, beyond the renowned

Okeanos, where the Greeks believed to be Tartarus, the son of

Iapetus - Atlas - transformed into a high mountain, supports the sky

on his shoulders.

The binomial Atlas-Hesperides was sought in vain by geographers and travelers who searched western region of the earth.

Three centuries after Hesiod, Herodotus - the Father of History - also searched the lofty mountain of the west. After traveling through Egypt and parts of Western Africa, Herodotus claimed to have located the famous Atlas!

The incredible episode is

described in his Book IV, Chap. 184.

Impressions of navigators who traveled along the Amazon more than three thousand years ago?

Exaggeration? Or would it be the length of a dangerous sea journey from the Northern Hemisphere down to the Southern hemisphere, and then sailing up the gigantic river, until the impressive gates of the Pongo de Manseriche?

A deep and narrow gorge that strangles the Marañón River, trough mountains that rise 600 meters,

In the Upper Marañón,

within the Pongo de Manseriche and its upper course, dangerous

whirlpools form with frequency.

On the left margin rises the Cordillera Blanca, named after its snow-covered mountains and glaciers. It is here that the Nevado Huascarán (6,746 m) towers over neighboring snowcapped peaks.

Continuing due south one

reaches the headwaters of the Marañón - and of the Amazon - in the

Cordillera Huayhuash, dominated by majestic Nevado Yerupajá Mountain

(6,617 m).

This is one of the most spectacular regions in South America.

According to Raimondi, in

the southern part of Ancash Department, the snow-clad Cordillera is

extremely impressive, and the traveler passing through this lofty

region is constantly surrounded by massive snowcapped mountains,

whose inaccessible peaks seem to be where earth and sky meet. 4

In fact, at the foot of these mountains, exactly as described in Hesiod's verses, we find a palace or, rather, the ruins of one, erected to the monstrous gods of antiquity. Ornamented with mythological monsters, this palace must have been a famous temple or oracle; the only one in the region that stands out for its impressive architecture constructed entirely of stone.

In the ruins of this

palace, known as Chavín de Huantar, and in museum galleries in Lima,

one can see the extraordinary works of art sculpted and engraved in

stone, whereby one can easily identify monstrous entities such as

the Gorgon, Cerberus and other children of Tartarus. Fig. I - 1: Map of Huascarán National Park with the world's higest tropical mountains, where the ruins of the Palace of Chavín de Huantar are located.

One reaches this site from Huaraz, the department capital, by way of the Southern Highway along beautiful Santa Valley, and then, from Catac, crossing the Cordillera Blanca (Fig. I - 1).

Prior to the archaeological work initiated by Julio C. Tello, in 1919, the ruins were partially buried under a thick alluvial deposit, accumulated from the runoff of the torrential Huacheksa Stream, that descends from the snowy peaks of the Uruashraju (5,722 m) and Huantsán (6,395 m) mountains.

The alluvial soil that

covered and protected the ruins was suitable for farming, and

eventually the inhabitants of the nearby village used the dressed

stones of the palace to erect their houses. 5

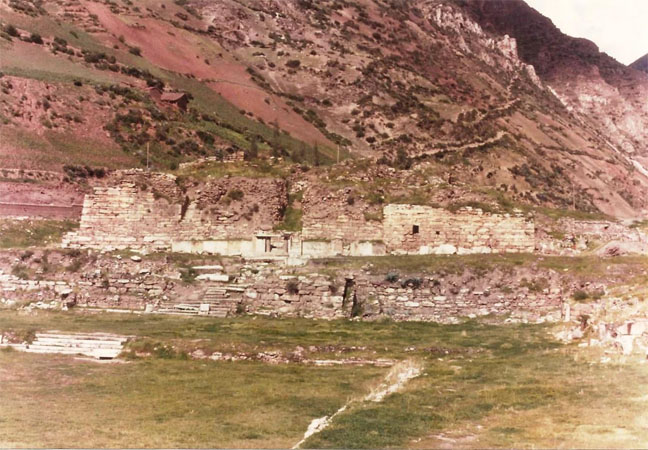

Though there is evidence of construction in stages, the layout and symmetry of the whole complex of edifices, stairways, plazas and subterranean canals, reveal great planning (Illus. I - 1 and 2).

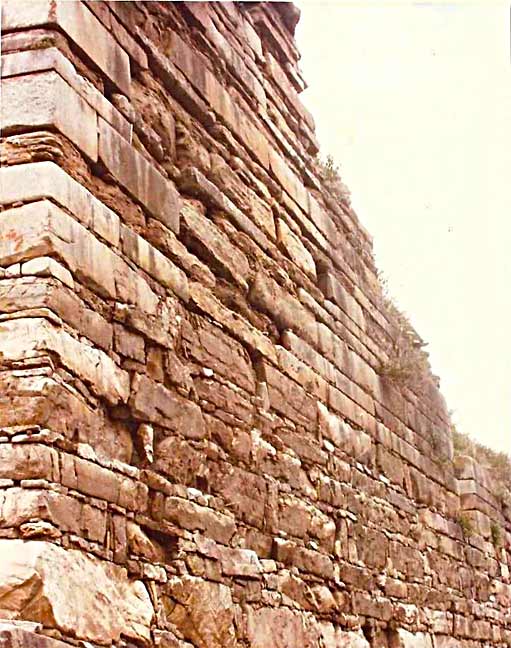

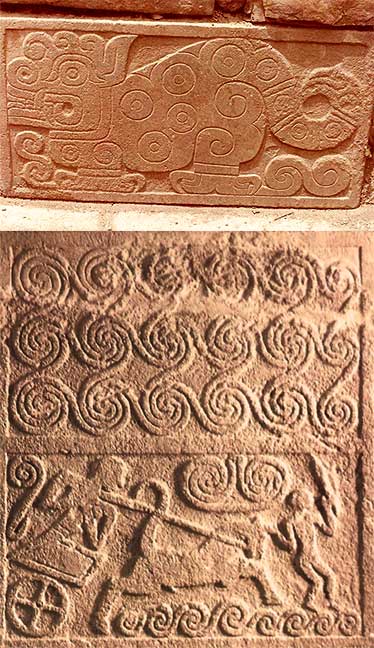

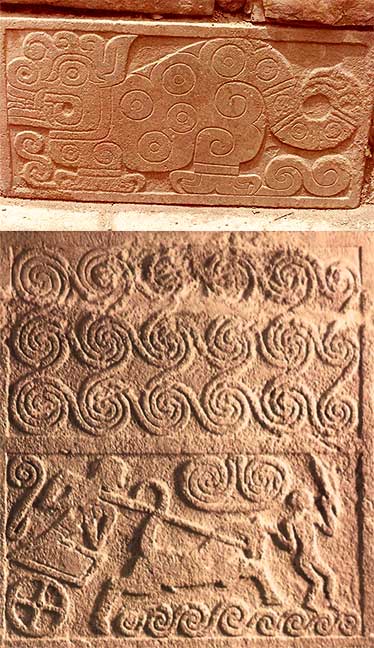

The architectural ornamentation consists mostly of ashlar masonry showing mythological representations carved in flat relief over granite, one of the hardest stones available (Illus. I - 5 and 6 and 10 top).

On the upper wall of the façades a series of monstrous heads were tenoned at regular intervals, which probably encircled the entire palace.

These granite heads, some weighing a half-ton, were supported by a rectangular tenon carved on the back, giving the impression of being suspended high on the walls without any means of support (Illus. I - 4 and 9).

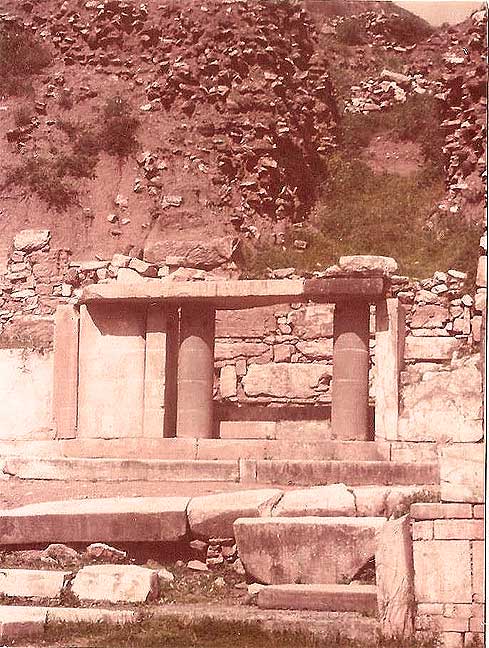

Two perfectly cylindrical granite columns, carved with highly stylized mythological figures, flank the Black and White Portal on the eastern façade (Illus. I - 3).

The iconography of Chavín Palace is impressive for the quality of its features and the originality of its design, revealing a creator of extraordinary architectural and artistic skills, rivaling the best works found in the Mycenae (Illus. I - 10 bottom) and Orcomenos grave steles, in Greece.

If this palace had been

unearthed there, no one would doubt the existence of Daedalus.

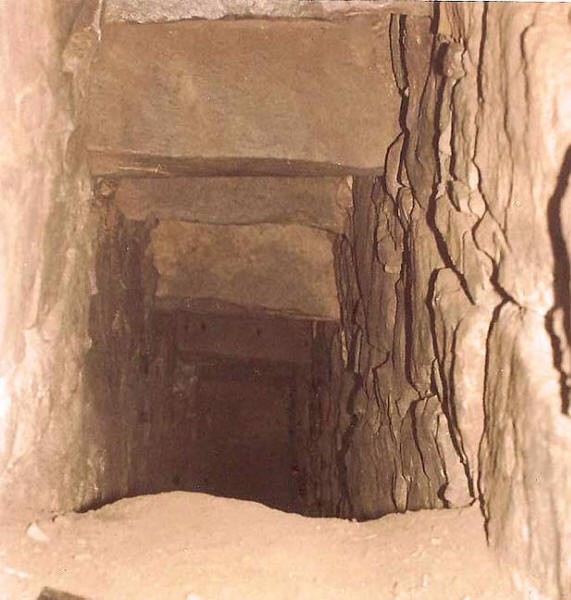

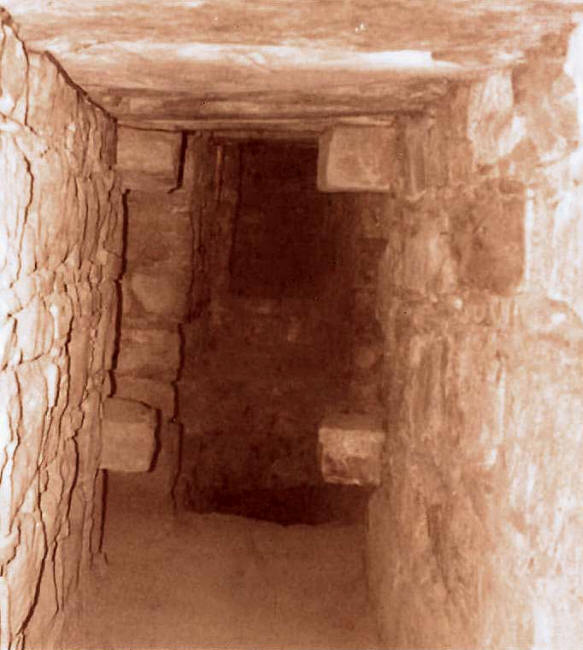

As shown in Fig. I - 2,

the edifice, which extends more than 10,000 square meters and

reaches a height of 15 m, has only narrow corridors, giving the

impression of a labyrinth.

Other smaller galleries link the principal labyrinth with a subterranean network which, by its inclination and lateral curvature, indicates that it was designed to convey water.

These galleries converge at a central aqueduct that extends from the façade of the principal temple to the Mosna River, passing below the stairways and the main plaza. The central aqueduct is slightly inclined, and its section of approximately two square meters, indicates that it carried an appreciable flow of water.

This work of hydraulic engineering, worthy of Daedalus, and for which specialists still have not found a satisfactory explanation, induces one to meditate on the apocalyptic gods represented in that edifice.

This labyrinth was the

starting point that led to a series of discoveries that became the

basis of the present physical interpretation of myths.

Fig. I - 2: Plan of the labyrinthine galleries of the Chavin Palace (according to J. C. Tello) with the principal edifice A, the oldest temple B, where the "Lanzon" is located, and edifice C extensively destroyed.

To maintain the secret of the subterranean mansion, a myth was spread, which perhaps not even its creator imagined would survive for such a long time.

The poets sang of the

deed of the hero who had challenged this abominable creature. Now,

dear reader, you will be taken to the Gorgon.

Due to the lance-like shape of the monolithic pillar, it was called "Lanzón."

The "Lanzón" was suspended from above like a gigantic knife ready to strike. It remained in that position, held firmly between two slabs of granite (or quartzite), forming part of the floor of the room above. While cleaning the galleries, in 1919, it was loosened from its original position.

With that lamentable

mishap, the pillar fell and lost its original alignment.

In the lower part, there are two laterally engraved cords, held doubly secure below the feet.

In the narrow room above, where once two large slabs of stone supported the "Lanzón," one finds the sacrificial room; very narrow and of peculiar shape, measuring 1.8 m in height. In this minuscule cubicle the victim was placed, after crossing a span by means of a ladder or a portable bridge.

The altar upon which the victim was sacrificed was not found though, from other sacrificial stones found in minor places of worship in the Andes, one can presume that the victim's blood ran through an orifice in the floor, dripping over the frightening image of the Gorgon.

Tello states that the victim's blood trickled down the front of the "Lanzón."

On that side there are two deeply engraved parallel grooves in the rock which, according to the archaeologist, were used to convey the blood from the sacrificial room down to a circular depression, as if it were the third eye of the Gorgon.

This depression is located in the middle of a cross engraved on top of the idol's head.

The arrangement of the double grooves, states Tello, allowed the recently sacrificed victim's blood to go directly into the mouth of the great divinity, before spreading down the grooves of the stone idol. 7

Another archaeologist,

Rebeca Carrion Cachot, believed that, besides blood, chicha (an

alcoholic drink made from corn) was poured down, and that the "Lanzón"

was the most ancient paccha, or rhyton, known in Peru.

8

If suffering and anguish could leave their marks on matter, that pillar would certainly contain all the lamentations of Hell. With that in mind, I extended my hand, closed my eyes and opened my soul.

Upon touching it, absolutely nothing happened; I only felt the cold surface, like a polished tombstone, as if it had been polished over a long period of time by the hands of nameless priests, with blood, fat and chicha, as it was usually done in ancient Peruvian rituals.

But, slowly I began to

feel ill at ease. An overwhelming force entered my soul, inciting me

to write without respite the results of my "journey."

A drawing of "Lanzón" showing South Face A and North Face B

He relates that the

palace appears to be an enormous fortress, more than 140 paces in

width and even more in length, and that there are figures of human

heads everywhere, admirably sculpted in stone, and which tradition

attributes to great antiquity, executed by men of high stature (as

he states, by giants), living there prior to the then governing

Incas. 9

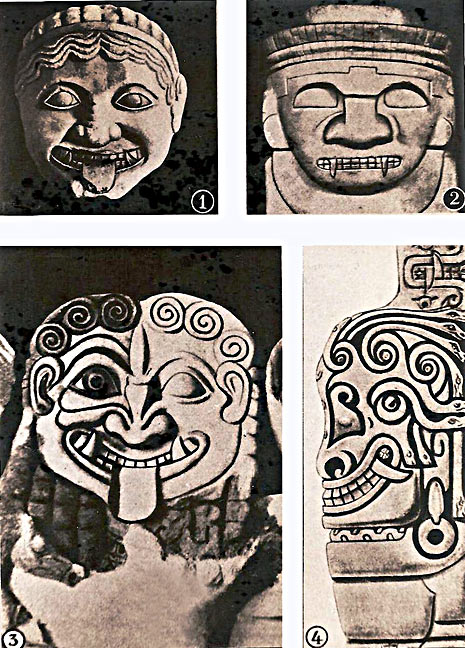

I don't believe that it is necessary to emphasize the similarity between the curve of the eyelids, the eyes and the nose. The relief that represents the lips forms an "ellipsoid" of the same relative size, inclusively curving its extremities upwards, with surprising fidelity.

However, the greatest

effect is provoked by the spirals that represent the hair

(transformed into serpents!) which in both compositions curl in the

same direction, and their number is identical. In reality these

facts arouse unexpected reactions in the mind of the observer.

But since the intention of Imbelloni was to demonstrate the impossibility of ancient contacts across the Atlantic, instead of following the logical path, he chose a dogmatic solution, stating:

And concludes:

That is, the resemblance between the Gorgonian images was so great, that it stretched the accepted limits of belief that they were culturally independent results.

In Imbelloni's time, there was no reliable method of determining the age of these archaeological monuments, and the hypothesis concerning the antiquity of the Peruvian civilization was wrong.

The influential Americanist Philip Ainsworth Means, for example, in 1919, believed that in the 13th century B.C., South America was a wild and uninhabited continent. 11

One is not concerned with the origin of mankind in South America (today, its presence can be confirmed as far back as 50,000 years ago). But one is certainly interested in the origin and evolution of the large pre-Colombian civilization of the continent (particularly, Peru), found in archaeological sites.

Through radiocarbon dating, archaeologists know that the Chavín culture, in its initial or formative phase, existed in various regions of Peru, as far back 1,600 B.C. 12

However, despite the

importance of this culture, there are no absolute dates available to

evaluate the age of Chavín Palace.

Another was initiated in 1972, with the collaboration of the archaeologist Herman Amat and his assistant, Marino Gonzales. 13

This last excavation was motivated by the tourist potential of the site, unearthing a circular plaza, 21 m in diameter, in front of the oldest temple, where the "Lanzón" stands.

However, despite the enormous volume of soil removed, no stratigraphic results or dates were presented, that could determine the age of the plaza, or at least, the period of its abandonment. This represents a real catastrophe for scientific archaeology, comparable to setting a library on fire.

The only data published corresponded to a charcoal sample found in one of the galleries of Chavín Palace, known as the Gallery of the Offerings, dating back to circa 780 B.C. 14

The fact that a skull and

many other human bone fragments along with other offerings were

found in the same gallery, could indicate that, already at that

time, the palace was completely abandoned. The galleries no longer

served their original functions, merely being used as a burial site

or a place to deposit ritual offerings.

Others point out that, during the Lumbreras excavations, in 1,967, several types of formative ceramics were found in the Chavín site. 16

Bennett also states that the ruins belonged to the first period of the Chavín culture. 17

By gathering together

these pieces of evidence one can tentatively estimate - until

further studies are carried out by a more technically capable team -

that the oldest section of the palace could have been built in the

second millennium before Christ, probably around 1,300 B.C.

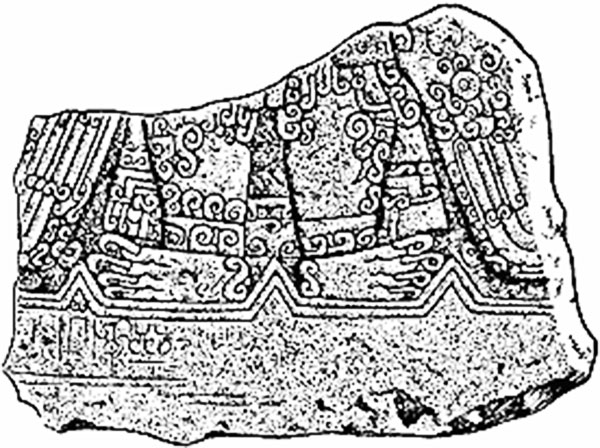

Fig. I - 4.

Gorgonian images from America and the Mediterranean

Nevertheless, some traditions were preserved, referring to "Huari" as a god and to the homonymous heroes called "huaris" or "guaris," endowed with supernatural powers, similar to the deity. These traditions - generally considered ridiculous or the work of the devil - were often extracted from the natives, under force or torture, by the iconoclastic clergymen.

Hence, the traditions of

the Conchuco region and nearby provinces, gathered in the 17th

century, are considerably fragmented and confused.

He distributed land to

each family, and taught them irrigation techniques. He also added

that he had a "seat" of stone to "sit on," and that he had arrived

in the form of a great and powerful wind. 18

"Huari-Viracocha" was feared because wherever he went, he would transform humans into stone.

This ancient tradition, quoted by the French researcher Pierre Duviols, is a priceless document because, in it, we find the Peruvian version of the myth of Perseus, or rather, a fragment of it, which the iconoclasts rescued unknowingly.

This interesting mythological fragment states: 19

Through these indigenous

traditions one can also deduce that the "House of the Huacas" was an

important oracle.

That identification is based on the description of the iconoclastic priest, Vega Bazan, who mentions a very large subterranean temple, constructed of large stone blocks, with extensive labyrinths, where the god "Huari" was worshipped.

According to Duviols, that description coincides perfectly with the temple of Chavín, because no other temple - or vestige of one - in ancient Conchuco Province fits Vega Bazan's description, except Chavín de Huantar.

Moreover, Duviols mentions the document by Vasques de Espinoza, who describes Conchuco Province without referring to any underground temple, except that of Chavín.

In that document, Vasques de Espinoza describes the temple of Chavín de Huantar: 20

After the archaeological works carried out at Chavín by J. C. Tello, in 1940, a series of monstrous heads was unearthed.

Considering the power

attributed to the Gorgon Medusa in transforming anyone into stone,

these heads with bulging eyes which formerly decorated the outer

walls of the temple, like trophy heads (Illus. 9a and 9b), are

petrified witnesses that allow one to identify Chavín with the abode

of the Gorgons, cited in Hesiod's Theogony.

Illus. I - 1. The Palace of Chavín, with the main plaza (foreground) and Wachecksa Gorge (upper right corner)

Illus. I - 2 Southeast corner

of the main temple of Chavín

Black and White Portal of the main temple, with two cylindrical columns of granite. The perfectly cylindrical columns were made by machine, in sectors, using a lathe.

Illus. I - 4: Rear view of Chavín Palace. The drawing, in the upper corner of the wall, shows the cornice with Cerberus-like figures. It also shows the original positions of the tenoned stone heads. Of the seven heads which were originally placed in the western wall, only two were found in situ by Tello's excavations. Note the wall inclination and the vertical periodicity of the stone-slabs: _.._.._.._.._.. (one thick, two thin, one thick, two thin,…).

The design is from J.C. Tello, "Chavin", Fig. 7, p.72.

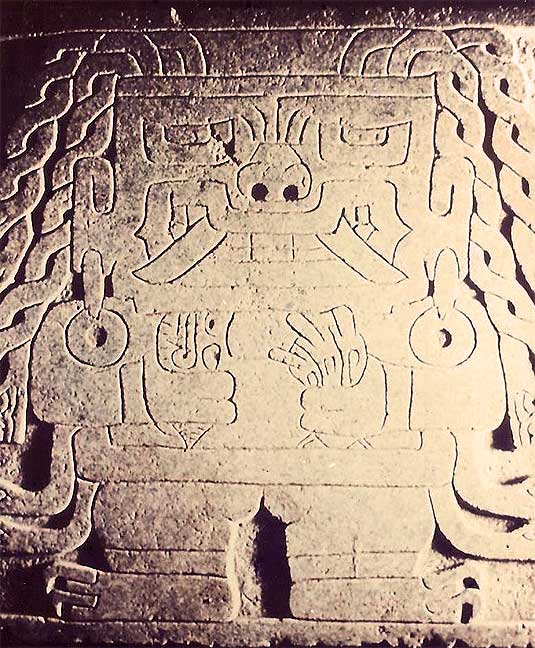

Illus. I - 5. Stele of a Gorgon, with 12 serpents. The hands are grasping shells, used as trumpets in rituals.

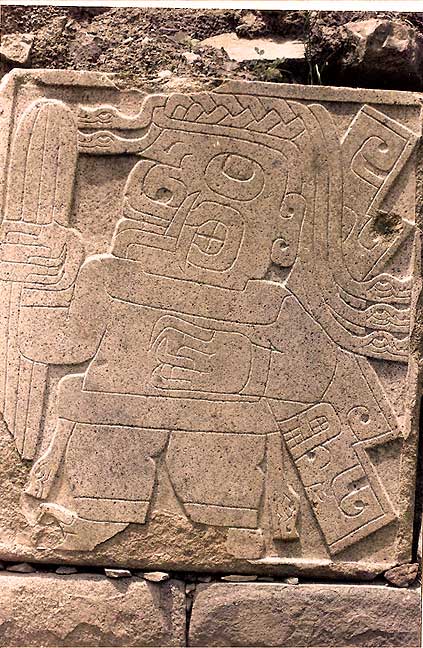

Illus. I - 6. Stele, in the circular plaza, of a three fingered Gorgon with two pair of wings, holding a club. For someone the figure holds a staff resembling stalks

of the mescaline- bearing San Pedro cactus.

Illus. I -7(a)

Illus. I -7(b). Labyrinthine gallery

in Chavín's Palace.

Illus. I - 8. South side of the Lanzón monolith with the Gorgon's large image

Illus. I - 9a. Stone head, which decorated the outer walls of Chavín Palace. According to Peruvian tradition, the stone heads, tenoned on the outer walls of the Palace, represented the "Huacas' who were petrified by the god Huari. Note the bulging eyes, linking them to the power of the Gorgon head, who transformed into stone

whoever gazed at her.

Illus. I - 9b. Stone head which decorated the outer walls of the Chavín Palace.

Illus. I - 10. (Top) Chavin's stele. (Bottom) Mycenae stele. Both with spirals and sigmoids.

The echoing resonance in the high mountains is mentioned in Hesiod's Theogony, which gave rise to the name "Resonant House of Hades and Persephone".

The article identifies the earliest representations of the "Fifty-headed dog of Hades" - Cerberus - found (and misnamed "feathered feline") in the excavations of the 21 m circular plaza, facing the oldest temple, where the great image of the Gorgon is found.

The article relates the vicissitudes of the Raimondi Stele, identified as the only existing representation in the world of the mighty Titan Typhoeus, as described in Hesiod's Theogony.

And, finally, it

discusses who were the people associated with the construction of

the main temple of Chavín.

Strange and powerful sounds echoed through its halls, protected by a guardian of the gates.

As the plan of the Chavín Palace complex shows (Part 1 Fig. I-2), adjoining the Old Temple (Building B), where the large image of the Gorgon stands, is the main temple (Building A).

On its eastern facade lies the Black and White Portal. The large carved lintel spanning the cylindrical columns is comprised of two types of stone. The southern half is white granite, and the northern half - of which only a piece remains - is black limestone.

Its name arises from the symmetric distribution of colors. 1

The flight of steps leading to the portico was also constructed with two types of stone joined in the middle, in perfect symmetry with the portal. One half, next to the Gorgon's temple is black limestone, and the other half is white granite.

This is the main temple of Chavín. Could it be the temple of the god "Huari"? It displays a notable portico, flanked by two perfectly cylindrical columns of hard granite. Engraved on the surface of these columns are mythological images of two "protective demons."

Yet, despite being the

main temple, no great image was found in it.

In that case, the temple of Persephone would be the Old Temple in which the large image of the Gorgon stands.

This identification of Persephone with the Gorgon Medusa should not surprise anyone reasonably familiar with Greek mythology, since the name is related to Perseus, her killer:

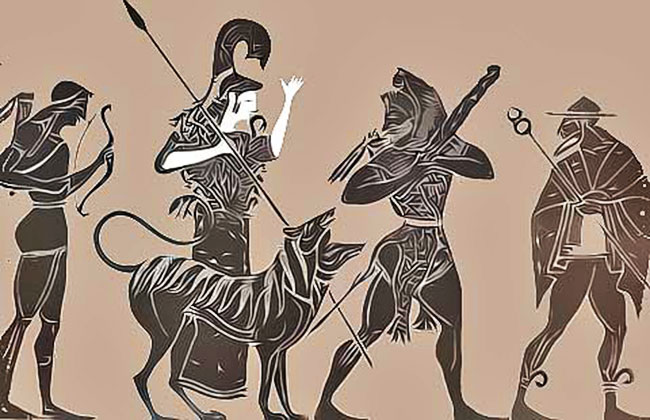

Fig. II - 1. Greek representation of Cerberus.

Fig. II - 2. Apollo, Athena, Heracles, Hermes and Cerberus on a Tyrrhenian amphora. Notice the serpent's head at the tip of Cerberus' tail.

Greek mythology makes reference to a wide gate offering access to the "subterranean abode," its threshold protected by a terrible monster, the dog Cerberus.

Hesiod quotes the monster in verses 311-312 of the Theogony:

The number of heads attributed to the watchdog of the Palace of Hades varies according to the author, sometimes having one, sometimes having fifty.

Also, its Mediterranean representations are not uniform. At times it is a common dog, at others it has leonine paws, or appears distinctly with serpents around its body (Figs. II 1-3).

What was the appearance

of that infernal creature where it actually guarded the entrance?

Rather than "feathered felines," one can call them mythological draconic images surrounded by serpents' heads.

Today, as in ancient times, it is difficult to determine the number of heads in that figure. Besides the principal head, there is another one at the tip of the tail, and two others sprouting from the jaw.

One of these figures is

surrounded by 9 serpents' heads, while the other has 11.

The representation, which is found on a Tyrrhenian amphora (Fig. II-2), shows the head of a serpent at the tip of the tail of the two-headed Cerberus, comparable to the figures of the Chavín cornice.

Obviously, a cornice could not be confused with a threshold.

Meanwhile, starting in 1,972, similar figures were discovered on the steles surrounding a circular plaza measuring 21 m in diameter, set in front of the Old Temple, forming the threshold of the central staircase that leads to the image of the Gorgon represented on the Lanzón (Illus..II - 1 and Illus.II - 2 Top).

Could the Chavin Palace

threshold be related to the threshold of the Palace of Night

mentioned by Hesiod?

Finally, comparing the steles of the aforementioned plaza to those of the first circle of tombs in Mycenae (Illus. II-2 Bottom), dating circa 1,500 B.C., one notes similarities in technique, the framing of the designs and the spiral motifs that decorate the central figures.

Therefore, besides the

Perseus myth, involving Mycenae and the Gorgon, Chavín also appears

to relate to Mycenae in technique and iconographic art.

The incredible art at Chavín is lavish and fantastic, such as the engraved design on a stone mortar fragment (Fig. II-5), found on the Chavín's site by Bennett, 6 and which was probably used for grinding medicinal plants.

The fragment bears the design of a mythological animal vomiting an unknown plant. The use of mortars appears to have been common in Chavín.

Tello dedicates five pages of his book to describing the various types of mortars found in the Chavín area and nearby sites. Some were unearthed intact, such as a massive diorite piece, 37 cm in length and 18.5 cm in height, sculpted in the shape of a mythological bird, the upper part hollowed out to form a rounded mortar, 16.5 cm in diameter.

Another piece found at Chavín, and which is presently at the University Museum, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Fig. II-6), represents a stone "feline," 33 cm in length and 16.5 cm in height, resting on four legs.

The "feline" is analogous to the aforementioned Cerberus-like monsters, engraved on the Gorgon temple threshold, at Chavín.

These objects, as well as other fragments used for the same purpose, were called "ceremonial mortars" by Tello. 7

To clarify this

intriguing question one must consult Greek mythology again.

Homer relates in the

Odyssey (I, 260) that Odysseus had sailed to Epirus in search of

φαρμαχονανδροφονον (fatal poison), the poison used on arrow tips.

The symbol of Asclepius, as well as the caduceus of Hermes, are similar to the one crowning the Raimondi Stele, one of the principal steles unearthed at Chavin.

It is said that Asclepius discovered the miraculous virtues of certain herbs on account of a serpent he injured, and which was cured by another one that carried a plant of miraculous properties in its gullet.

Convinced that everything has a cause, including illness, he worked to discover what was noxious to human health and what was able to reanimate mankind. He was worshipped in forests, medicinal springs and on high mountain tops.

The temple of Asclepius, in Athens, had a hot spring.

The god appeared in the

dreams of the sick and gave them remedies for their illnesses.

Its temple was the house of death.

However, other buildings of Chavín Palace were used to recover one's health, not only through the words of the oracle, but also by way of medicinal herbs, prepared and ground in stone mortars.

The buildings - most probably used to treat the health of pilgrims visiting Chavín - must have been on the south side. One kilometer from this point, to the right of the modern road following the Mosna River, is a hot spring, which waters could easily have been piped to the temple.

This spring, according to Raimondi, emits sulphurous waters at a temperature of 45°C. 8

Here, again, we find the dual symmetry, so common in the architectural elements of Chavín: the Black and White Portal and the black and white flight of steps in front of it - which had to symbolize life and death.

To the left of the black

steps, on the side of the Old Temple where the Gorgon stands, was

the house of death; to the right of the white steps, where medicinal

water flows, was the house of life.

The Image of Typhon

on the Raimondi Stele

One day, in 1840, while cultivating his land, a simple farmer, Timoteo Espinosa, found a large, well-cut and polished rectangular stone slab, on which was a carved image of a fearful god surrounded by many serpents.

He took it home to use as

a table. 10

Finally, in 1874, it was

transported by the sergeant major José Manuel Marticorena,

with great effort and using nearly two quintals (200 kg) of

explosives, in one hundred detonations, to remove the rocks blocking

the narrow paths in the Andes, between Chavín and Casma.

In Lima, it was placed over bricks in a rustic, black wooden frame, exposed to the elements, in the courtyard of the Exhibition Palace.

The people called it "the Inca Stone."

The more curious visitors admired the great number of serpents which the complicated design bore; yet, according to José Toríbio Polo, no one gave it the least artistic or historical importance. 11

As if forty years of selfless work by Raimondi to Peru were in vain, two years after his death, in 1892, the stele was found completely abandoned near a weir, beside the Exhibition Palace, used as a plaything by children.

Toríbio Polo's complaints were a patriotic gesture to save the stele which otherwise would be sold to a foreign museum for a few thousand pounds sterling.

After it was moved twice, from one museum to another, the irreparable happened.

The stele, having

survived three millennia; escaping undamaged from the hands of the

peasants, who cooked and ate on it and which safely crossed the

Cordillera of the Andes, was now broken into pieces in the hands of

those responsible for its safety.

The 17-cm thick stone parallelepiped measures 1.95 m high, 76 cm wide at the bottom, and 73 cm at the top. 13

However, neither the rock's dimensions nor type are important; rather, it is the elaborate carving on one of its surfaces. The high-relief design, engraved by the champleve technique, 5 mm deep, reveals a masterpiece of rare artistic conception, and executed with perfect symmetry by a steady and sure hand.

Its discoverer thought highly of it from the moment he examined it, stating: 14

And continuing:

In his notebooks, unpublished until 1943, Raimondi wrote:

All those who afterwards delved into Chavín's archaeology, at least once, tried to describe or interpret the engraved image on the stele. Some, like Tello's, were so detailed that the whole perspective was lost. 16

When reading scholars' interpretations, rather than being enlightened, an air of doubt and gloom arises, with little hope of ever understanding its significance.

Looking at these

interpretations and a dozen others which space does not allow one to

include, one could say that the Raimondi Stele acts like a magical

mirror, reflecting what is in each person's thoughts.

Who could discover its meaning merely by analyzing the elements represented in the image?

One must acknowledge the

impossibility of finding a satisfactory answer by this method. There

are innumerable examples of fruitless attempts to interpret myths

and legends based solely on the elements contained therein.

One must analyze quantitatively the engraved elements on the top half of the monstrous creature on the Raimondi Stele (Fig. II-7):

Uhle, for example, called them scolopendrid's legs (centipede's legs).

Imitating the archaic style of the Theogony, the god represented on the stele can be described as follows:

The artist who carved

this "son of the earth and sky," wanted to personify destructive

forces, represented by fifty serpents' heads and a hundred arms,

as well as the powerful weapons held in his hands.

Fig. II - 7.

Design of the Raimondi Stele.

These elements, together

with the monstrous heads with darting tongues, allow one to identify

it with Typhon.

Once again, oracle-like, one finds the answer in Hesiod's Theogony, 147-153:

The poet, facing the stele, could not have described it better:

No one was able to describe it as accurately as Hesiod's verses, depicting these Titans or giants, called Εκατογχειρες (Hecatoncheires), "which have a hundred arms."

The coincidence with the

god on the stele is quantitative as well.

Chavín Palace was erected to these gods and its fame reached beyond all borders.

The Nahoas or

Nahuatlacas, an ancient and cultured people who lived in Mexico

prior to the Spanish conquest, had also preserved the tradition of a

homonymous god, whom they called "Ehecatonatuih," meaning the "Sun's

Wind," the fourth and final one, who caused great destruction to

mankind. 22

In light of the present comparison, where we find an ancient Greek description of a deity coinciding with the image on the Raimondi Stele, we might be lead to interpret these Hecatoncheires as a myth describing three images at Chavín Palace.

However, this hypothesis is not completely satisfactory, since the Hesiodic myth splits into a fourth, similar entity, Typhon or Typhoeus, the apocalyptic god, characterized by infernal "theophonia" 23 (Theogony, 820-835):

Now, with Hesiod's help, one can appreciate the monstrous heads which the Gorgonian deity carries upon its shoulders, the enormous dragons' mouths, darting triangular tongues that seem to utter incomprehensible sounds that remain crystallized in stone.

The Hesiodic description

portrays Typhon as similar to the hundred-armed deity found on the

Raimondi Stele.

That hypothesis induced me to question the fundamental concepts of Peru's archaeology and proto-history.

It began after my first visit in 1981, when I realized that the labyrinthine structure of Chavín Palace could have been constructed for acoustic purposes, so as to simulate the sound of the gods.

These sounds (which shall be called "theophonia" from the Greek theo = god or the gods, and phonia = sound), along with the frightening appearance of the gods represented in Chavín Palace, must have caused a terrifying effect.

To unravel that burning question I returned to Chavín in January 1,983, to search for any signs of sound-generating structures that could have produced and amplified them within the galleries of the palace.

With the help of the custodian of the archaeological site, Gregorio Perea Martinez, I was able to verify that, in fact, the audio-visual setting of the ancient palace, where the personifications of the Gorgon, Typhon, and Cerberus were identified, must have been extremely sophisticated.

The worshippers of the Underworld were impressed not only by frightful images, but also by terrifying acoustic effects, that could have been produced inside the palace.

Perea showed me the underground galleries, which were constructed to handle a considerable flow of water. I was able to walk inside the central duct, located below the main plaza. Its nearly 2m2 section could have handled the water from several of the palace's galleries, channeling it to the Mosna River.

Today, the rear outline of the channel entrance, which carried the captured waters of the Wacheksa Stream, is unknown. The frequent landslides, and the construction of a road behind the palace ruins, destroyed all evidence of the channels.

Fortunately, along the front of the temples, on the eastern side of the palace, one can still find some ducts, vertically orientated or sharply inclined, as shown in Fig. II-8.

These ducts, which shall

be termed "excitators," as can be deduced from a simple analysis of

its internal structure, could have been excited by a stream of

water, yielding thunderous sounds, similar to conventional organ

tubes when excited by a stream of air (Fig. II-9).

On top is a lateral canalization, where the water entered, before falling into the vertical duct. The ducts are rectangular, and are formed by properly laid stone slabs.

An important detail allows them to be characterized as acoustic "excitators": on the lateral canalization, through which the stream of water entered, there is an overhanging stone slab (on the upper part of the vertical duct), forming a type of tongue, which forced the stream of water to form an arc, as shown in Fig. II-9 by points B and F.

The isolated air in

chamber C began to oscillate and the labyrinthine galleries of the

palace, in communication with the "excitator" through the acoustic

duct D, started to resonate, producing and reinforcing sound.

Fig. II - 8. Longitudinal section of the channel located below the flight of steps in front of the oldest temple, where the "Lanzón" lies. The cross-section shows the acoustic duct, beneath the "tongue", which probably

connected this "excitatory" to the labyrinth. by Luis G. Lumbreras, Arqueologicas N° 15. Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Museo Nacional de Antropología y Arqueología.

Instituto Nacional de Cultura. Lima, 1974.

But, understandably, due

to the small quantity of water and the inappropriate means to excite

it, they were unable to produce any sound at all.

Though the timid efforts

of the archaeologists were unable to prove anything, this does not

mean that more than 3,000 years ago the builders of the palace, who

appear to have been far more capable than the excavators, were able

to achieve hydroacoustic sounds, for which all evidence indicates is

the reason for the construction of the labyrinth at Chavin Palace. Fig. II - 9. Right drawing shows the longitudinal section of a hypothetical subterranean acoustic "excitator",

stimulated by hydraulic energy. C. Well where the air oscillate, stimulated by falling water; D. Acoustic duct connecting chamber C with the labyrinth E; F. Flow of water. Left drawing shows the longitudinal section of an organ pipe, stimulated by compressed air.

Chavin's steles with Cerberus-like figures, located on the threshold of the Circular Plaza of 21 m, in front of the Old Temple of the Gorgon. These steles were carved in identical pairs, and it is likely that were originally seven pairs

on each

side of the staircase.

Illus. II– 2. (Top) Chavin's stele. (Bottom) Mycenae stele. Both with spirals and sigmoids.

Top view of an acoustic excitator with the flagstone removed, located in front of the main palace of Chavín.

The arrow indicates the direction of the water flow.

A second acoustic excitator, in front of the main palace of Chavín.

Homer, describing the aegis of Athena (Iliad, V, 741 and 742), says:

...and further on (Iliad,

XI, 32-37), describing the armor of Agamemnon, the greatest Greek

hero who fought at Troy, quotes again the horrible Gorgon, with its

frightful gaze.

Odysseus, fearing that

Persephone, the goddess of the Underworld, will send the frightful

head against him, abandons the House of Hades and sets out to

navigate the deep ocean currents.

Pindar (Pythian, XII, 30) relates that the music was invented by Pallas Athena, on the occasion of the Gorgon's death. Athena invents the flute, composed of canes and thin sheets of bronze, inspired by a sinister melody produced by the groaning of the Gorgon and the hissing of serpents.

Beyond the constant association of Medusa with the emission of sound, another important observation is that beneath some shrines, where Medusa was represented in stone, ran a stream of water.

When describing the monuments of Argos, Pausanias relates that beneath the sanctuary of Cephisus one could hear the flowing of a river.

At this point it is appropriate to remember the remarks of Professor Marinatos:

The following discussion

of evidences about the origin and meaning of Chavín - still

unpublished - is launched here in advance of the second part of my

book, in preparation.

...the apocalyptic gods were "enchained".

The Palace of Chavín, in its time, was the most important oracle and religious center, not only in the Andean region, but in all South America.

Chavín was

comparable to Delphi and possibly was founded as a

copy of it. Obviously, all these sacred stones received blood

sacrifices, as the blood of sacrifices offered to massebáh

(standing stones in Semitic shrines and temples) and bethels (sacred

pillars) by Canaanites.

Which is most surprising, its name is not of Greek origin.

As we shall see, the

toponymy of places near Chavín, with remains of old monuments, as

well as the same name Chavín, indicate a Semitic or Canaanite

origin.

The Quechua words are

without the letters b, c, d, g, v, x and z. so, Baal could not be

spelled in Quechua, and was lost.

The earliest Phoenician attestation of Baal-Shamem comes from Building inscription from the 10th century B.C. of King Yehimilk in Byblos. Here Baal-Shamem is named before the 'Lady of Byblos' and 'the assembly of the gods of Byblos'.

He represents the summit of the local pantheon.

This is also true for the Karatepe inscription dating for the last decades of the 8th century B.C., where he heads a sequence of gods, being named before 'El, Creator of the Earth'.

In the Luwian version of this bilingual inscription, the 'Weather-god of Haven' corresponds to Baal-Shamem. Later, in the Hellenistic period, a temple at Umm el-Amed is dedicated to Baal-Shamem.

In Greek inscriptions from this region he is called,

At Hatra, in North

Mesopotamia, Baal-Shamem (various spellings b'lsmyn, b'smyn and

b'smn) had his own sanctuary. 25

Onga or Onka, which is the Phoenician name of Athena, is related to Cadmus.

When Cadmus was leaving Delphi, told by the oracle to follow the route of the Sun, he discovers an immense serpent, against which he wages a victorious battle.

He sows its teeth, from which emerge armed warriors, who fight each other to the death. With the five remaining survivors, he founds a town as ordered by the oracle, where he established a cult of Athena Onga.

See the geographic

interpretation of Cadmus myth in my book "Journey

to the Mythological Inferno", Chapter IV.

The wall portrays a war scene in which two columns of warriors approach each other from opposing sides amidst the carnage of their adversaries.

The engraved stones represent severed human bodies writhing in agony; triumphant warriors are adorned with severed heads, bleeding heads of defeated soldiers and a stone with a large pile of decapitated heads.

The stone frieze at Sechín is one of the oldest dated Andean stone carving known at the present time, dating in the middle of the second millennium B.C. 27

Richard L. Burger,

without the slightest intention of suggesting a Semitic influence on

Sechín, compares the bloody scene with the biblical Joshua'

conquest of Jericho.

I suggest that Figure

IV-5 shows a nautical quadrant engraved on the stone, and Figure

IV-6 shows a Phoenician-like vessel. I believe that the toponymy of

Sechín could be Semitic, homonymous to the Canaanite town of

Sechem, also spelled Sichem.

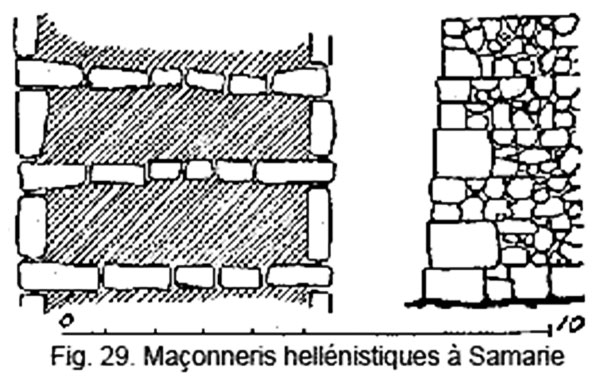

Samarian stone masonry, with the wall inclination and vertical periodicity of stone-slabs: (one thick-two thin) as the Chavín's walls of the "New Temple". See Illus. I - 4 (Part 1). After: A.G. Barrois, O.P. "Manuel D'Archéologie Biblique"

Tome I,

p. 115, Paris, 1938.

Fig. II - 11. Fragment of stele found in Chavín. Showing part of an engraved Babylonian? or Assyrian? style god. Under his feet it is possible to distinguish several Greek letters of an inscription. Dimensions: 1.25 m wide and 0.74 m height. After: "Chavín" J.C. Tello, p. 226.

In the second millennium B.C., Canaan, Crete, and what is now Greek territory, formed a single cultural entity.

Herodotus (II-44; IV-147ff.; VI-47; etc…) knew about the early Phoenician contact with them (Greeks). 30

It is worthy noting that

their combined presence (Phoenician and Greeks) is also confirmed in

ancient Perú.

|