|

by

Jiri Mruzek

from

RedIceCreations Website

Are the World's Biggest Building Blocks Prehistoric?

In 27 BC, the Roman Emperor Augustus supposedly took the unfathomable

decision to build in the middle of nowhere the grandest and mightiest temple

of

antiquity, the Temple of Jupiter, whose platform, and big courtyard are

retained by three walls containing twenty-seven limestone blocks, unequaled

in size anywhere in the world, as they all weigh in excess of 300 metric

tons. Three of the blocks, however, weigh more than 800 tons each. This

block trio is world-renowned as the "Trilithon". antiquity, the Temple of Jupiter, whose platform, and big courtyard are

retained by three walls containing twenty-seven limestone blocks, unequaled

in size anywhere in the world, as they all weigh in excess of 300 metric

tons. Three of the blocks, however, weigh more than 800 tons each. This

block trio is world-renowned as the "Trilithon".

If we think within the official academic framework of history,

Augustus had

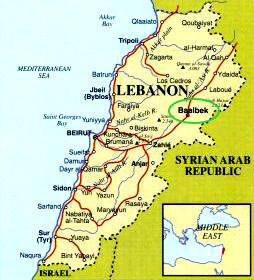

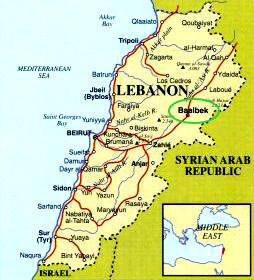

no obvious reasons for selecting Baalbek as the temple's building site.

Supposedly, Baalbek was just a small city on a trading route to Damascus

through the Bekaa valley in Lebanese mountains, about sixty kilometers from

the Mediterranean coast (34º lat., 36º long.) It was of no special religious

significance, apart from being in the centre of a burial region, in the midst of thousands of rock cut

tombs.

But, lavishing great architecture on Baalbek then seems totally out of

character for the undeniably selfish Rome, which had at the very same time

been stealing historic treasures from other countries, such as the obelisks

from Egypt. It makes more sense that Baalbek had something no other place

could offer, not even the city of Rome, the heart of the empire.

This

something may also be the reason why so many people wished to be buried

there. Indeed, it has been noted that the blocks in the retaining wall

of the Baalbek temple site clearly look a lot more eroded than

the bona fide Roman ruins of the Temple of Jupiter, as well as those of the

other two Roman temples also on the site.

Therefore, the heavily eroded

blocks should be much older.

|

Bonfils, ca. 1870. Negative inscribed "468. Mur Cyclopeen a Balbek."

Albumen. Unmounted.

11 x 9 inches.

© 1996 Middle East Section.

Joseph Regenstein Library.

The University of

Chicago |

This fact naturally gives rise to a different scenario: At

Baalbek Rome had

found a fabulous ready made foundation, a mighty platform to add a suitably

majestic structure to, stamping the Roman eagle upon the whole for the

perception of future generations.

Material Evidence

The much greater erosion of the big Baalbek blocks qualifies as material

proof of their much greater age. The issue really seems rather simple. This

is how the stone looks when it is almost like new after having

been recently sanded.

However, sanding did not get rid of the deep pits,

signs of either considerable previous erosion, or the product of drilling,

if not both. |

Circumstantial Evidence

One also finds plenty of circumstantial evidence undermining the official

version of Trilithon's origins:

a) Absence of Baalbek records.

Above all, Rome records no claim to the incredible retaining wall.

b) Presence of other records of actual Roman transport capabilities.

Elsewhere in the Roman empire, just a little over 300 metric tons seemed to

be the limit for the transport of big blocks, achievable only with the

greatest difficulty. Transport of the 323 ton Laterano obelisk to Rome

spanned the reigns of three emperors. Clearly, the record setting engineers

from Baalbek, had they existed, could have also managed the task of

transporting the relatively light Lateran Obelisk.

The fact that they were nowhere to be found, no matter, how crucial the

task, indicates that they simply did not exist.

c) Baalbek was an important holy place.

The Ptolemys conferred the title of Heliopolis upon

Baalbek. Therefore, like

the other Heliopolis (Sun City) under Ptolemys' domain in

Egypt, it had to

be an ancient holy place, it must have had some notable architecture, and

the two places had to have some connection. I suggest it was the titanic

blocks that instilled awe in everybody. In Phoenician times,

Baalbek had

supposedly been a religious centre devoted to Baal. Local Arab legends place

the cyclopean walls (the Baalbek Terrace) into the time of Cain and

Abel.

d) Roman and Megalithic styles of building.

Orthodox scholars of today scoff at all suggestions that Romans had not

brought the great blocks to the temple site, despite the fact that building

with megalithic blocks was not at all in the Roman style, and was no longer

practiced in those days. Romans knew and used concrete. The Colosseum still

standing in Rome is a good example of a classic Roman concrete structure.

|

The sad truth is that regarding the

Trilithon, some scholars have mental

blocks its own size. Admissions that blocks weighing over a 1000 metric tons

were quarried and transported in prehistoric times would invite

uncomfortable questions on what technology had made it all possible.

Regardless of such touchy issues, I have several personal observations,

which support dating of Baalbek's megalithic walls to the megalithic era.

Have a look at this nice northwestern view of the wall (right image) as it was circa 1870.

|

|

The wall has two distinctly contrasting parts:

-

One forms the bulk of the wall, five layers of considerably eroded blocks.

Several such blocks also survive in the sixth layer. Sizes of these blocks

vary from big to unbelievably big, the largest building blocks anywhere.

-

The second part is a later Arab addition. Its blocks differ by being:

The Arabs had a fortress here. It was devastated by wars and finally by a

major earthquake several centuries ago. The Romans must have left the old

sacred enclosure walls as they were, and concentrated on building the

temples. They had no need for defensive walls like the Arabs.

|

The top corner of the

northern block of the Trilithon is well rounded by erosion, and

human abrasion. One of the newer, small blocks rests directly on

this eroded, round spot. So, when it was lain into this position,

the damage was much like it is today.

It is evident that one block is a lot older than the others, as the

position of the newer blocks marks the extent of erosion in the

older blocks at the time |

If the big blocks were to be

Roman, then the newer Arab blocks would mark

the erosion of the older Roman blocks as it was after the first six or

seven-hundred years. But, how could this erosion be a lot greater than the

subsequent erosion of both the old and the new blocks in twice as much time?

In the details below, we can see that whoever had added the smaller blocks

(presumably also limestone, and coming from the same quarry, the nearest one

to the temple), had made adjustments for erosion in the old ruin, which are

visible as steps, or notches in the elsewhere straight line of the newer

blocks.

The eroded blocks seem to have been hewn flat on top to facilitate

the laying of additional blocks.

Of the four blocks atop the eroded blocks, each is at a different horizontal

level |

|

|

Time to Draw the Line

A horizontal line was cut into the older block. It seems to continue the

bottom line of the neighboring newer block quite exactly. The red line you

see is there to show this fact.

I believe that the cut

line had marked the top portion of the older block, which was to be

cut away, so that the newer blocks could be set level. Thankfully,

the plan was not carried out for some reason. |

Consequently, we

have a clear clue to what had happened here.

Because the line in the eroded block survives about as well as the newer

blocks, the two materials must be similarly durable.

It then follows that by the apparent rate of aging, the heavily eroded

blocks should be at least several millenia older than the newer blocks.

Ergo, the older part of the wall cannot be Roman.

|

Hadjar el Gouble (the Stone of the South) 1,170 metric tons

In a quarry about half a mile away from the Trilithon is an even bigger

block It measures 69 x 16 x 13 feet, ten inches, and weighs about 1,170

metric tons.

There is a belief, the block was slated for the retaining wall,

but was later found to be too big. Thus, it was abandoned in the quarry

while still joined to the bedrock at one end. |

|

The important question is, was it younger, or was it older than the three

Trilithon blocks? It seems that it had to be made later than the

Trilithon.

If it was made first, and then deemed to be too big, it would have still

been utilized, rather than quarrying a new block, the Romans would have

simply whittled the big block down to a more manageable size. We would not

see it in the quarry today.

On the other hand, despite their brilliant ability to move about burdens as

unprecedented as the Trilithon, the unknown architects lost their nerve at

the very end, the big block looming almost ready. There was no attempt to

move the practically finished block. This just does not behoove the solid

Roman engineers, especially the creme de la creme entrusted with the task by

the Emperor himself. Why did they leave behind a monument to their

engineering limits and human weaknesses, and by extrapolation - Roman

emperor's limitations?

Again, this would be very un-Roman of them, and even

more so in view of what the same engineers saw at Aswan. It is a fact that

the big block still in a Baalbek quarry seems to weigh about the same as the

famous abandoned obelisk at Aswan, Egypt. Here, the question begs itself if

this really is by chance.

How could the two biggest ever blocks of quarried stone coincide in weight,

despite being made in different eras, by different techniques, and abandoned

for different reasons? Not likely, is it?

This thread gets funnier, when we learn that the fifty-four enormous columns

for the Jupiter's temple actually came from Aswan! There the Roman engineers

could not have missed witnessing the abandoned 1,170 ton obelisk, which the

Egyptians had obviously intended to move, prior to discovering that it was

cracked, a fatal flaw.

Did the obelisk somehow inspire Romans to quarry a block of the same weight

(albeit not proportion) at Baalbek, and then abandon it, when almost

complete, mimicking the Egyptians ad absurdum, every inch of the way? Monkey

see, monkey do? Is this not insane?

Another theory holds that work on the block stopped, when Rome suddenly

became Christian, and stopped all construction on the site. That is of

course impossible, because the retaining wall with the big blocks was long

complete by then, and where else would the big block go, other then the

retaining wall? So, none of the explanations makes sense

Then there is that utter lack of documentation for these stunning exploits,

which should have been proudly noted by Roman historians, politicians, and

so on. It's a little like if American history books skipped the fact that

America went to the Moon. Meanwhile, local legends ascribe the stones to the

time of Genesis. The big blocks were part of a fortress built there by Cain.

So, did Romans move the Trilithon blocks? Absolutely not! Romans had no

desire to move such weights, because they knew just as well as we do that

they could not move even substantially smaller blocks. History supports our

notion with solid evidence from the same time period.

When Augustus, emperor of Rome had conquered the region in 27 BC, he ordered

that the massive obelisk towering above others at the Karnak temple in Egypt

be brought to Rome, but the effort was aborted, when the trophy proved too

heavy. Sources give varying estimates of its weight, from 323 tons to 455

tons.

The discrepancy must stem from the fact that the original obelisk was 36

meters long, and had weighed 455 tons. Now that it is 4 meters shorter at

the base, it must be correspondingly lighter, and because obelisks are

always considerably thicker at the base than higher up, the loss of a

hundred tons would be realistic. So, the discrepancy is self-explanatory.

It seems to suggest a reason to why some 300 years later, Emperor

Constantine I (reigned A.D. 306-337) had succeeded where Augustus had

failed, namely, in taking the obelisk out of Egypt. But, in the process, the

pedestal and a large part of its base were destroyed. Well, since we are

talking about the otherwise indestructible Aswan granite, we have to deem

the obliteration of the thickest, strongest part of the obelisk deliberate.

Unable as they were to move the whole obelisk, the Romans had taken only as

much as they could carry.

After all, Constantine's workers had similar

troubles with the obelisk of Tuthmoses III now standing in

Istanbul. Here is

a quote I found at Andrew Finkel's site:

"The decision to import the structure was taken by

Constantine himself. Rome

had at a dozen obelisks. His city, Constantinople or the "New Rome" had to

have at least one. The Byzantines succeeded in fetching the monument from

Deir el Bahri near Thebes, although in a sawn-off form. The original shaft

was probably a great deal longer. Yet having brought it to the harbor on

the Sea of Marmara side of the city, no one could figure out for an entire

century how to get it up the hill"

At the same time the big 323 ton Lateran obelisk from

Karnak was still in

Alexandria, remaining there until after Constantine's death. His son,

Constantius II [reigned A.D. 337-340] had then taken it to Rome instead.

However, it did not get to Rome's Circus Maximus until A.D. 357, seventeen

years after the death of Constantius II. Finishing the centuries old project

took almost fifty years...

Knowing all these facts then bears heavily on our judgment of what the

Roman could, or could not do at Baalbek.

a) Roman engineers had failed to even budge the 455 ton

Thutmoses' obelisk

at Karnak for emperor Augustus.

b) But, allegedly, the same Roman engineers had successfully transported the

three Trilithon blocks weighing twice as much, plus, twenty-four more blocks

weighing pretty well as much, i.e., 300 - 400 tons, all of which we see in

the enclosure wall of the Baalbek temple terrace.

Moreover, the transport of the

Trilithon blocks would have had been

incredibly rapid, because the retaining walls should be in place prior to

the construction of the temple itself, as logic would seem to dictate

Unable to move the 455 ton Karnak obelisk, Augustus took two other obelisks

from the Sun Temple in Heliopolis, instead. It was the first transport of

obelisks to Rome. The obelisks are now in the Piazza del Popolo (235 tons),

and the Piazza di Montecitorio (230 tons). Funny, 235 + 230 = 465. So,

Augustus got his 455 tons, plus change, but it was in two parts.

These are

solid indications of the then Roman capacity in moving heavy objects.

|

|

Why did Romans pick the remote

Baalbek? Did they do it for practical

reasons, utilizing older structures, and perhaps plentiful building

materials already onsite?

Even the fifty-four enormous yet typically

Roman columns from Aswan granite,

which had once surrounded the courtyard, of which six are still standing

(image left),

may be pre-Roman, but later recarved in the Roman style. Despite being as

magnificent as they are, the spectacular and unprecedented construction

achievements at Baalbek were not heralded to the world as its own by the

proud and glory hungry Rome.

Why not? |

Making such a claim would have been impossible, if the world already knew

about the awesome Baalbek ruins, of course.

If Roman and other writers had

failed to mention the great Baalbek blocks, they were in

amazing sync with

the modern day's attitude.

|

antiquity, the Temple of Jupiter, whose platform, and big courtyard are

retained by three walls containing twenty-seven limestone blocks, unequaled

in size anywhere in the world, as they all weigh in excess of 300 metric

tons. Three of the blocks, however, weigh more than 800 tons each. This

block trio is world-renowned as the "Trilithon".

antiquity, the Temple of Jupiter, whose platform, and big courtyard are

retained by three walls containing twenty-seven limestone blocks, unequaled

in size anywhere in the world, as they all weigh in excess of 300 metric

tons. Three of the blocks, however, weigh more than 800 tons each. This

block trio is world-renowned as the "Trilithon".