|

by Immanuel Velikovsky

from

VArchive Website

THE TEMPLE AT DAN

The story of Jeroboam, son of a widow of Zereda, an Ephraimite and

Solomon’s servant, begins with this passage:

Solomon built Millo, and repaired

the breaches of the city of David, his father.

And the man, Jeroboam, was a mighty man of valor; and Solomon,

seeing the young man that he was industrious, made him ruler

over all the charge of the house of Joseph.1

The ambitious servant was not satisfied

with this honor of administering the land of Menashe (Manasse) and

Ephraim, or even the entire northern half of the kingdom; he wished

to be a king himself. When Jeroboam’s plans became known to Solomon,

the king intended to kill him, but Jeroboam ran away to the Pharaoh

of Egypt.

When Solomon died, he returned; he tore

the ten tribes’ land from Rehoboam, son of Solomon. Solomon’s realm

was split in two: Jeroboam became king of Israel in the north, and

Rehoboam retained the kingdom of Judah in the south. To make the

rift permanent Jeroboam had to keep the people from going to

Jerusalem and its new temple.

And Jeroboam said in his heart, Now

shall the kingdom return to the house of David.

If this people go up to do sacrifice in

the house of the Lord at Jerusalem, then shall the heart of this

people turn again unto their lord, even unto Rehoboam, king of

Judah, and they shall kill me, and go again to Rehoboam, king of

Judah.2

From the viewpoint of serving his own ends, it was a sound idea to

build on some ancient sites places for folk gathering which would

compete with Jerusalem.

Whereupon the king [Jeroboam] took counsel, and made two calves of

gold, and said unto [his people]. It is too much for you to go up to

Jerusalem...

And he set the one in Beth-el, and

the other put he in Dan.3

Beth-El was in the south of his kingdom,

close to Jerusalem, Dan in the north of his kingdom. In order to

attract pilgrims from the land of Judah, Jeroboam also made Beth-El

the site of a new feast, “like unto the feast that is in Judah”.4

Setting up the image of the cult in Dan, Jeroboam proclaimed:

“Behold thy gods, O Israel, that

brought thee up out of the land of Egypt.“5

Thus, Dan in the north competed with

Jerusalem in the days of Passover and Tabernacles. The temple of Dan

was a much larger edifice than the temple in Bethel, and it became a

great place for pilgrimage, attracting people even from the southern

kingdom.

And this thing became a sin; for the people went to worship before

the one [of the two calves], even unto Dan.6

The temple of Dan was called a “House of High Places” :

“And he made an house of high

places...” 7

The Temple of Jerusalem was also called

a “House” in Hebrew.

For centuries the temple of Dan in the north successfully contested

with the Temple of Jerusalem, and attracted throngs of pilgrims.

Jeroboam, the man who supervised under Solomon the building of

Millo,

the fortress of Zion with its strong wall, and who, in recognition

of his ability demonstrated in this work, was appointed governor of

the northern provinces, now, when king, must have desired to erect

in Dan a temple surpassing the magnificent Temple of Solomon in

Jerusalem. Only in offering a more imposing building could he hope

not only to turn the people from going to Jerusalem, but make the

people of Judah elect a pilgrimage to Dan over one to Jerusalem.

Meanwhile, Jeroboam had seen the temples

and palaces of Egypt, and his ambition was, of course, to imitate

all the splendor he had seen in Jerusalem, in Karnak, and in

Deir

el-Bahari. Or would this “mighty man of valor”, industrious

constructor of Zion’s citadel, and a shrewd politician, try to

contest the Temple of Jerusalem by means of an ignoble chapel? That

he succeeded in his challenge is a testimony to the size and

importance of the temple at Dan.

It was not enough that Dan and Beth-El were ancient places of

reverence: magnificence was displayed in the capital of Solomon, and

magnificence had to prevail in the temple cities of the Northern

Kingdom.

The temple of Beth-El, the smaller of the two Israelite temples, was

demolished three centuries later by King Josiah, a few decades

before the Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar. It

was trampled into smithereens by the king, jealous for his God.8

There is no mention of a destruction of the temple in Dan. Where was

Dan and its “House of High Places” ?

THE SEARCH FOR

DAN

Dan was the northernmost point of the Israelite settlement where one

of the twelve tribes chose its domicile. A familiar expression was:

“From Dan even to Beer-Sheba.” 9

Students of biblical geography have agreed to place Dan in the Arab

village of el-Kadi, on the upper flow of the Jordan, which is there

but a rivulet. In recent years very insignificant ancient ruins have

been found on this place.10

This is in accord with what the biblical archaeologists expect, for

they think the temple of Dan to have been a very modest structure of

which, most probably, hardly any ruins would have remained.

The biblical Dan is placed on the upper flow of the Jordan because

of a passage in Josephus Flavius. In his Jewish Antiquities,

Josephus says that Dan was on “a spot not far from Mount Libanus and

the sources of the lesser Jordan”.11

Commentators of Josephus deduced that by

the “lesser Jordan” the upper flow of the Jordan, above the Lake of

Huleh, or above the Lake of Tiberias, is meant; however, this

interpretation is not supported by the words “not far from Mount

Libanus” since, from the surroundings of el-Kadi and the sources of

the Jordan, the snow-capped Hermon or Anti-Lebanon can be seen in

the distance, but not Lebanon, far behind the Anti-Lebanon.

After having chosen the source of the Jordan as the area where to

look for Dan, this ancient city was located at el-Kadi for the

following reason: the name Dan is built of the Hebrew root that

signifies “to counsel” or “to judge”. El-Kadi means in Arabic “the

judge”. There was no other reason, beside this philological equation

of Hebrew and Arabic terms, to locate the site of the ancient temple

city in the small village of el-Kadi, since—until quite recently—no

ruins, large or small, were found on the site.

The aforementioned reference in Josephus makes one wonder whether by

“the lesser Jordan” the river Litani was meant. This river begins in

the valley between Mount Lebanon and Mount Anti-Lebanon, flows to

the south in the same rift in which farther to the south the Jordan

flows, and towards the source of that river, but changes its course

and flows then westwards and empties itself into the Mediterranean.

Its source being near Mount Lebanon, it appears that the Litani was

meant by “the lesser Jordan”.

However, Josephus, who wrote in the first century of the Christian

era, was not necessarily well-informed concerning the location of

Dan - the temple city of the Northern Kingdom - a state whose

history ended with the capture of Samaria by Sargon II in -722.12

Therefore, it is only proper to go back to the Scriptures in trying

to locate Dan.

THE PORTION OF

THE CHILDREN OF DAN

When the Israelites, after the Exodus from Egypt, roamed in the

wilderness, they sent scouts to Canaan to investigate the land and

to report. The scouts passed the land through its length “from the

wilderness of Zin unto Rehob, as men come to Hamath”.13

These were also destined to be the

southern and northern borders of the land:

“Your south quarter shall be from

the wilderness of Zin” and in the north “your border [shall be]

unto the entrance of Hamath”.14

The expressions “as men come to Hamath”,

or “unto the entrance of Hamath” signify that Rehob, the northern

point of the land visited by the scouts, was at a place where the

road began that led to the city of Hamath in Syria.

In the days of conquest under Joshua son of Nun, when the land was

partitioned by lot, the tribe of Dan received its portion in the

hilly country on the road from Jerusalem to Jaffa. The tribe was

opposed by the Philistines, also invading the same country. When the

population of Philistia increased through the arrival of new

immigrants from the Mediterranean islands, the tribe of Dan, being

the advance guard of the Israelites, had to suffer not mere

resistance, but strong counter-pressure.

The Samson saga reflects this struggle.

Tired of continuously opposing the increasing influx of the

Philistines, the Danites migrated to the north.

They... came unto Laish, unto a

people who were quiet and secure; and they smote them with the

edge of the sword, and burned the city with fire.

And there was no deliverer, because it was far from Zidon, and

they had no business with any man; and it was in the valley that

lieth by Beth-Rehob. And they built a city, and dwelt therein.

And they called the name of the city Dan... howbeit, the name

of the city was Laish at the first.15

Here we meet again the northern point

Rehob or Beth-Rehob. We are also told that it was situated in a

valley. Next to it was the city of Laish, and the Danites burned the

city and then erected there a new city, Dan.

Beth-Rehob, or House of Rehob, is the place we met—in the story of

the scouts sent by Moses—as the most remote point they visited going

to the north.

The place was “far from Zidon”; if it were where it is looked for

today—at the source of the Jordan—it would not have been proper to

say “far from Zidon”. but rather “from Tyre”. But if Zidon (Sidon)

is named as the nearest large city. Tyre must have been still

farther from Laish-Dan, and the latter city must have been more to

the north, in the valley between Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon.

The Danites were in contact with the Zidonians already at the time

when they fought with the Philistines for the possession of

territory. Because of want of land, they sent many of their sons as

sailors on Phoenician ships.16

In their new place of abode the Danites became kindred with the

Phoenicians.

In Dan-Laish, “the children of Dan set up the graven image” of

Micah.17 The story of

this holy image is connected with the migration of the Danites to

the north. Before migrating they sent a few men to find for them “an

inheritance to dwell in’”.18

These men traversed, on their errand, the mountainous land of

Ephraim. Micah was an Ephraimite who built a private chapel in Mount

Ephraim, where he placed “a graven image and a molten image”, and

hired a Levite to serve there as a priest.19

The men of Dan, dispatched on the errand to find a new domicile for

the tribe, heard an oracle from the priest.

After having spied the place of Laish,

they returned to their tribe that dwelt in the hilly borderland of

Zarah, and with six hundred warriors went to the north. Passing

again Mount Ephraim, they took with them the image and the priest,

despite the bitter protests of Micah. When they conquered Laish “the

children of Dan set up the graven image”.20

Since then, there was an oracle in Dan.

The name Dan-jaan, found in the Scriptures,21

is apparently a synonym for Dan: it means “Dan of answer”, or “of

oracle”.

Dan became the site of the temple built by Jeroboam. It was a holy

place long before he built his temple there, since the story of the

oracle of Micah is conspicuously narrated in the Book of Judges; it

is rather probable that Rehob was a sacred place even before the

Danites built their city on the ruins of Laish close by.

It cannot be said of the present village of el-Kadi that it lies on

the road “as men come to Hamath” ; to satisfy this description,

Rehob must be looked for farther to the north.

THE SUCCESSORS

OF JEROBOAM

Being located in an outstretched part of the Israelite kingdom, Dan

was often the subject of wars between the kings of Damascus and of

Israel. Shortly after the death of Jeroboam, the temple city was

conquered by the king of Damascus.22

It appears that, at the time of the revolution of Jehu, three

generations later, in the ninth century, Dan was still in the hands

of the kings of Damascus; but it is said that Jehu, who destroyed

the temple of Baal in Samaria, did not destroy the temple of Dan,

nor did he abolish its cult, “the sin of Jeroboam”.

This implies that Dan came back into the

hands of the Israelites in the days of Jehu. In any case, the

population of the northern kingdom -that of Israel—but also of the

southern kingdom - that of Judah-continued to go to Dan on the

feasts of Passover and Tabernacles, preferring it to Jerusalem.

Jehu, jealous of the God

Yahweh, did nothing to keep the people from

going to Dan, and obviously even encouraged them to do so; the cult

of Dan was one of Yahweh, though in the guise of a calf, or Apis.

In the eighth century the prophet Amos, one of the earliest prophets

whose speeches are preserved in writing, spoke of the worship at

Dan:

They that swear by the sin of

Samaria, and say, Thy god, O Dan liveth; and, The manner of

Beer-Sheba liveth; even they shall fall, and never rise up

again.23

For a time Amos prophesied at Beth-El,

the other sacred site of the Northern Kingdom. In his time the place

had a royal chapel; and in view of the statement that, of the two

places where Jeroboam placed the calves, the people went to worship

in Dan,24 apparently

the chapel of Beth-El remained a minor sacrarium and did not attract

many worshippers.

Hosanna, another prophet who lived in the eighth century,

admonished:

“Let not Judah offend... neither go

yea up to Beethoven.” 25

He prophesied also that the “inhabitants

of Samaria shall fear because of the calves of Beethoven”, and that

the glory of that place will depart from it.26

It is generally agreed that Hosea, speaking of Beth-Aven (“the House

of Sin” ), referred to Beth-El This is supported by the verse in the

Book of Joshua which tells:

“And Joshua sent men from Jericho to

Ai, which is beside Beth-Aven, on the east side of Beth-El”

27

It appears that the name Beth-Aven, or

“The House of Sin” was applied to both places where Jeroboam built

temples for the worship of the calf. It is possible that, in another

verse of his, Hosea had in mind the temple of Dan; he said:

“The high places also of Aven, the

sin of Israel, shall be destroyed...”

28

“The sin of Israel” is the usual term

for the cult of Dan; and the “high places”, according to the quoted

story of Jeroboam placing calves in Dan and Beth-El,29

were built in Dan.

At the beginning of the Book of Amos, the following sentence

appears:

“I will break also the bar of

Damascus, and cut off the inhabitant from the plain of Aven (me’bik’at

Aven)... and the people of Syria shall go into captivity unto

Kir...“30

I shall return later to this passage and

to the accepted interpretation of “the plain of Aven”.

During the wars of the eighth century, the temple city of Dan may

have taken part in the struggle of the Northern Kingdom for its

existence, being oppressed first by Syria, and then by Assyria. Dan

may have been besieged, and may have changed hands during these

wars, but nothing is known of its destruction.

In the latter part of the eighth century the population of the

Northern Kingdom was deported by Sargon II to remote countries, from

where it did not return. More than a century later Jeremiah referred

to the oracle of Dan: “For a voice declareth from Dan”,31

which shows that the oracle of Dan was still in existence after the

end of the Northern Kingdom.

An oracle venerated since ancient times, a magnificent temple where

the image of a calf was worshipped, a place where the tribes of

Israel gathered in the days of the feasts, and the people of Judea

used to come, too—this was the cult.

On the way to Hamath, on the northern frontier of the Northern

Kingdom, closer to Zidon (Sidon) than to Tyre, and strategically

exposed to Damascus—this was the place. Would no ruins help to

identify the site?

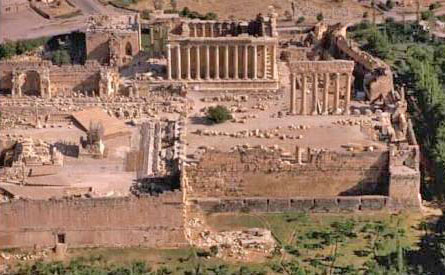

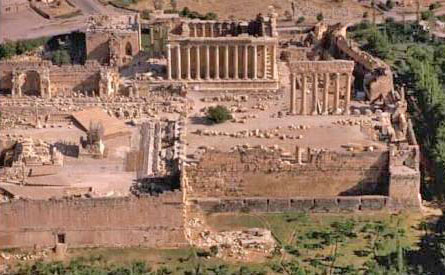

BAALBEK

In the valley that gives birth to two rivers of Syria—the Orontes

flowing to the north, and the Litani flowing to the south and west,

between the mountains of Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon, where roads from

Palestine in the south, Damascus in the east, and the sea-coast on

the west meet and run from there to Hamath in Upper Syria—lie the

ruins of Baalbek.

When we compare the ruins of Baalbek with those of many ancient

cities which we visited in Italy, Greece, Egypt, and in other parts

of Asia (and Africa), we cannot help thinking them to be the remains

of the boldest plan we ever saw attempted in architecture. Is it not

strange then, that the age and the undertaker of the works, in which

solidity and duration have been so remarkably consulted, should be a

matter of such obscurity...? 32

From the time when this was first written, in the fifties of the

eighteenth century, and till today, nothing was added to dispel the

obscurity which envelops the origin of this temple city.33

The excavations undertaken there brought no solution to the problem

of its origin or the nature of its cult.34

No early inscriptions were found.

Throngs of travelers who spend their day wandering among the ruins

of a magnificent acropolis go away without having heard what the

role of the place was in ancient times, when it was built, or who

was the builder. The pyramids, the temples of Kamak and Luxor, the

Forum and Circus Maximus in Rome were erected by builders whose

identity is generally known.

The marvelous site in the valley on the

junction of roads running to Hamath is a work of anonymous authors

in unknown ages. It is as if some mysterious people brought the

mighty blocks and placed them at the feet and in front of the

snow-capped Lebanon, and went away unnoticed. The inhabitants of the

place actually believe that the great stones were brought and put

together by Djenoun, mysterious creatures, intermediate between

angels and demons.35

SOLOMON’S BAALBEK

Local tradition, which may be traced to the early Middle Ages,

points to a definite period in the past when Baalbek was built: the

time of Solomon.

Ildrisi, the Arab traveler and geographer (1099-1154), wrote:

“The great (temple-city) of

astonishing appearance was built in the time of Solomon.”

36

Gazwini (d. 1823 or 4) explained the

origin of the edifices and the name of the place by connecting it

with Balkis, the legendary Queen of the South, and with Solomon.37

The traveler Benjamin of Tudela wrote in the year 1160 of his visit

to Baalbek:

“This is the city which is mentioned

in Scripture as Baalath in the vicinity of the Lebanon, which

Solomon built for the daughter of Pharaoh. The place is

constructed with stones of enormous size.”

38

Robert Wood, who stayed at Baalbek in

the 1750’s, and who published an unsurpassed monograph on its ruins,

wrote:

“The inhabitants of this country,

Mohomedans, Jews and Christians, all confidently believe that

Solomon built both, Palmyra and Baalbek.”

39

Another traveler who visited Syria in

the eighties of the eighteenth century recorded:

"The inhabitants of Baalbek assert

that this edifice was constructed by Djenoun, or genies in the

service of King Solomon.” 40

ON - AVEN

The identification of Bikat Aven, referred to in Amos 1:5 with the

plain of Coele-Syria is generally accepted.41

The text, already quoted, reads: “I will break also the bar of

Damascus, and cut off the inhabitant from the plain of Aven . . .”

The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Bible by the Seventy,

renders the above text as “the valley of On,” written the same as On

(or Heliopolis) in Egypt. The Hebrew spellings of Aven and On do not

differ in consonants; and vocals were inserted in the texts by the

Masoretes in a late period.

On is the Hebrew name of Heliopolis in

Egypt, pronounced also as Aven, as in Ezekiel 30:17; Bikat Aven is

the name of the plain of Baalbek in Amos. Tradition has it also that

the cult of Baalbek was brought there from Heliopolis in Egypt.42

Hosea, however, called by the name of Aven (Beth-Aven) the cities of

Bethel and Dan;43 and

he spoke of “high places” there, and in the instance where he

referred to “the sin of Israel” he obviously meant Dan.44

Amos, who in the eighth chapter speaks against the worshippers at

Dan, in chapter one speaks against the plain of Aven—and thus,

comparing Hosea and Amos, one wonders whether Amos 1:5 speaks of

Baalbek or of Dan.

The expression Bikat Aven, or the Valley (Plain) of Aven in Amos

impelled the exegetes and commentators to refer the place to Coele-Syria,

and this because Bi’qa is the specific name of the Coele-Syrian

plain—still in use today. The very name Baalbek is generally

explained as the Baal of Bi’qa or Bekaa—of the valley.

Baalbek is situated in the valley between Lebanon and Hermon. Of

Dan

it is also said that it was situated in a valley:

”...And it was in the valley that

lieth by Beth-Rehob. And they built a city, and dwelt therein.”

45

BAALATH, BAAL GAD,

BAAL ZAPHON, BAAL MELECH

Is Baalbek the Scriptural Baalath, as Benjamin of Tudela thought?

About Baalath it is said:

“And Solomon built . . . Baalath,

and Tadmor in the wilderness.” 46

Tadmor is Palmyra, far to the northeast

of Baalbek. Baalath is said to have belonged to the tribe of Dan.47

Or, is Baalbek the Scriptural Baal Gad? deliberated a few scholars.48

It is said:

“Baal Gad in the valley of Lebanon

under mount Hermon.” 49

In the valley of Lebanon under mount

Hermon lies Baalbek. If this identification is correct then Baalbek

was inside the Israelite kingdom. However, against this supposition

of Baal Gad in the valley of Lebanon it was argued that the

Israelite kingdom never embraced the area of Coele-Syria, or the

valley between Lebanon and Hermon (Anti-Lebanon).50

Some writers would regard Baalath and Baal Gad as two names of one

place and would locate it at Baalbek.51

If Solomon built in Palmyra in the desert between Syria and

Mesopotamia, the region of Coele-Syria between Lebanon and Hermon

could certainly be in the area of his building activity, argued

these scholars. But placing Baal Gad in Coele-Syria, where would

they place Dan, the northernmost point of the Kingdom of Israel? To

keep Dan in Galilee and to place Baal Gad, an Israelite city, one

hundred fifty kilometers farther to the north will not stand up

against the indisputable fact that Dan was the northernmost city in

Israel.

Some scholars, looking for Baalbek in the Scriptures, identified it

with Baal-Hamon, referred to in the Song of Songs.52

And again, Baal Hamon is supposed to be another name for Baalath and

Baal Gad.53

Also Baal Zaphon, or Zeus Cassius, was proposed as Baalbek.544

In this connection it can be said that, according to the Talmud, Gad

was the name of the planet Jupiter;55

and Zeus Cassius signifies Jupiter of Lebanon; and Hamon was

supposed to be a Syrian form of the name Amon56

who, according to the Greek authors, was Zeus-Jupiter.57

All this together, if correct, points toward the cult of Jupiter in

Baalbek, a matter to which we shall return in one of the next

sections.

Besides Baal Gad, Baal Zaphon or Zeus Cassius, Baal Hamon, and

Baalath, one more name is identified as Baalbek: Baalmelech, or “the

royal Baal”.58

THE TRILITHON

Already in the last century it was observed that the Acropolis of Baalbek and the temples built on it date from different epochs. The

massive substratum—the great base of the acropolis—appears to be of

an earlier date; the three temples on the substratum, of a later

date.

It is even probable that the wall of the acropolis did not originate

in one epoch. Among the stones of which it is built there are three

of an unusual size—almost twenty meters long. Each of them weighs

about one thousand tons. These huge monoliths are incased in the

wall. The question arises whether they are not the survivals of the

original cyclopean structure—that which carried the name Rehob, or

Beth-Rehob, and which served as a landmark for the scouts dispatched

by Moses in their survey of Canaan, and for the emissaries of the

tribe of Dan in their search for the territory in the north.

Like Stonehenge in Great Britain, or

Tiahuanaco in the Andes, it may have originated in an early time—not

necessarily Neolithic, since it appears that these stones are

subjected to hewing by metal tools.

In the quarry a mile away is found another stone of comparable size,

cut out of the rock from all but one side; it appears that this

stone of more perfect cut was quarried in a later time, possibly in

the days of Jeroboam, or even later; but, for probably mechanical

considerations, the work was not finished and the stone not removed,

and the emulation of the early builders not completed.59

In another place I intend to return to the problem of

the Trilithon

of Baalbek, when treating cyclopean buildings and the mechanical

means of quarrying and transporting these monoliths.

THE EMBOSSED

QUADERS

Aside from the incased trilithon, the attention of the visitor to

Baalbek who inspects the wall of the acropolis is drawn to stones of

a bossed shape with an indented rim on all four sides of the face of

the stone.

O. von Richter in 1822 60

and S. Wolcott in 1843 61

drew attention to the fact that the quaders of the wall of the

temple area of the acropolis of Baalbek have the same form as the

quaders of the Temple of Solomon, namely, of the surviving western

(outer) wall, or Wailing Wall. The Roman architects, wrote Wolcott,

never built foundations or walls of such stones; and of the

Israelite period it is especially the age of Solomon that shows this

type of stone shaping (chiseling).

The photograph of the outer wall of

Baalbek’s temple area illustrates that the same art of chiseling was

employed in the preparation of stones for its construction. Whatever

the time of construction of other parts of Baalbek’s compound—neolithic,

Israelite, Syrian, Greek, or Roman—this fundamental part of the

compound must have originated in the same century as the surviving

(western) wall of the area of Solomon’s temple.

THE TEMPLES OF

THE ACROPOLIS

The buildings on the flat plateau of the Acropolis have columns with

capitals of Corinthian style.

The time of the origin of these

temples is disputed. An author of the last century62

brought forth his arguments against a late date for the temples atop

the acropolis; he would not agree to ascribe them to the Roman

period, or Greek period; he dated them as originating in an early

Syrian period: the Romans only renovated these buildings in the

second century of the present era.

The opinions of scholars are divided over whether these buildings

can be ascribed to Roman times, though the source of the designs on

the doorways and the ceiling and in the capitals of the columns

speak for a Roman origin. When the Roman authorship of the buildings

is denied, the Romans are credited only with renovating the

structures.

The Emperor who is sometimes said to have built the largest of the

temples in the temple area—that of Jupiter—is Aelius Antoninus Pius

(138-161). The source of this information is the history of John of

Antioch, surnamed Malalas, who lived not earlier than in the seventh

century of this era, and wrote that Antoninus Pius built a temple

for Jupiter at Heliopolis, near the Lebanon in Phoenicia, which was

one of the wonders of the world.63

Julius Capitolinus, who wrote the annals of Antoninus Pius and

enumerated the buildings he erected, offers no material support for

the assertion made by the Syrian writer of the early Middle Ages.

Though Antoninus Pius did build in Baalbek, as is evidenced by his

inscriptions found there,64

his activity was restricted to reparation of the temples or the

construction of one of the edifices in the temple area.65

The work in its entirety could not have

been his because Lucian, his contemporary, calls the sanctuary of

Baalbek already ancient, and because Pompey had already found it in

existence and Trajan consulted its oracle.

The style of the temples caused the same divergence of opinion as

the style of the surviving ruins of Palmyra. Some regard them as

Roman,66 others as

Hellenistic and Oriental.67

They are sometimes called East-Roman.68

In the case that only the ornamentation is of the Roman period the

question may arise whether the walls and the columns of these

buildings could be of as early a period as the seventh century

before the present era, or the time of Manasseh, of whom Pseudo-Hippolytus

says that he reconstructed Baalbek, built originally in the time of

Solomon.69

THE CALF

It was almost a common feature in all places where pilgrims gathered

to worship at a local cult that diminutive images of the deity were

offered for sale to them.

Also small figures of the god or of his

emblem in precious or semi-precious metals were brought by

worshippers as a donation to the temple where the large scale figure

had its domicile.

In Baalbek archaeological work produced very few sacred objects or

figures that could shed light on the worship of the local god.

“It was a disappointment, next to

the brilliant success of so rich an excavation, that nothing was

learned of the nature of the deity and the history of its

worship.” 70

Figures of Jupiter Heliopolitanus

standing between two bullocks or calves have been found at Baalbek,

dating from Roman times.71

In addition, an image of a calf was also found.

The only figure of an earlier time found in Baalbek is an image of a

calf. Since it is to be expected that images found in an ancient

temple are reproductions of the main deity worshipped in the holy

enclosure, it is significant that the holy image in the temple of

Baalbek was that of a calf, and of no other animal.

The name Baal-Bek (Baal-Bi’qa) is sometimes transmitted by Arab

authors as Baal bikra, or Baal of the Steer or Calf, which is the

way of folk etymology to adapt the name to the form of the worship

practiced in the temple. This, together with the finding of the

images of the calf in the area of the temple, strengthens the

impression that the god of Baalbek was a calf.

THE ORACLE OF

BAALBEK

Baalbek or, as the Romans called it, Heliopolis, was venerated in

the Roman world as the place of an old cult of an ancient oracle,

and it rivaled successfully other venerated temples of the Roman

Empire.

It is known that the Emperor Trajan, before going to war against the

Parthians in the year 115, wrote to the priests of Baalbek and

questioned its oracle. The oracle remained in high esteem at least

as late as the fourth century of the present era, when Macrobius in

his Saturnalia wrote of Baalbek:

“This temple is also famous for its

oracles.” 72

Was it the ancient oracle of Micah? In

the words of Jeremiah, shortly before the Babylonian exile of -586

in which he spoke of “a voice... from Dan”,73

we had the last biblical reference to the oracle of Micah. In the

days of Jeremiah the oracle must have been seven or eight hundred

years old. Did it survive until the days of Trajan and even later,

until the days of Macrobius?

In the Tractate Pesahim of the Babylonian Talmud is written the

following sentence: “The image of Micah stands in Bechi.”

74 Bechi is known as the

Hebrew name for Baalbek in the time of the Talmud. As we have seen,

in the Book of Exodus it is recounted that the Danites, migrating to

the North, took with them Micah and his idol, and that it was placed

in Dan of the North. The Talmud was composed between the second and

the fifth centuries of the present era.

This passage in the Tractate Pesahim is a strong argument for the

thesis of this essay, namely that Baalbek is the ancient Dan.75

TWO

PROBLEMS: A SUMMARY

The problems will be put side by side. Dan was the abode of the old

oracle of Micah. Jeroboam built there a “house of high places”, or a

temple. Previously, he was the builder of Jerusalem’s wall under

Solomon; before becoming king of the Northern Kingdom he lived as an

exile in Egypt. He introduced the cult of the calf in Dan.

The new temple was built to contest and to surpass the temple of

Jerusalem. It became the gathering place of the Ten Tribes, or “the

sin of Israel”, and pilgrims from Judah also went there.

The prophets, who opposed the cult of Dan, called the place

Aven,

like Aven, or On (Heliopolis) in Egypt.

Its oracle was still active in the days of Jeremiah, in the

beginning of the sixth century.

Dan was the northernmost city of the Kingdom of the Ten Tribes, and

the capital of the tribe of Dan. It was situated in a valley. If

Baal Gad, between the Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon was not the same

place, Dan must have been more to the north.

The place was at the point where the roads meet that run toward

Hamath.

No ruins of this temple-city are found. Where was Dan and its

temple?

Remains of a great temple-city are preserved in Baalbek.

At the

beginning of the present era it was described as already ancient. It

bore the name of Heliopolis, like the Egyptian On, or

Aven

(Ezekiel); and Amos, who spoke against the worshippers at Dan,

prophesied the desolation of Bikat-Aven, or the Valley of Baalbek.

Its cult was introduced from Egypt. During excavations, the figure

of a calf was unearthed.

The temple possessed an old oracle. The Talmud contains the

information that the oracle of Micah (which according to the

Book of

Judges was in Dan) stands in Baalbek.

Local tradition assigns the building of the temple of Baalbek to the

time of Solomon. The wall of the temple area is built of great stone

blocks of the same peculiar shape as those of the Wailing Wall in

Jerusalem, the remains of the outer wall of the temple area erected

by Solomon.

Baalbek lies in a valley (Bi’qa) between the Lebanon and the

Anti-Lebanon, and on the junction of the roads that connect Beirut

from the west and Damascus from the east with Hamath in the north.

The history of the temple-city of Baalbek in pre-Roman times is not

known, neither is its builder known, nor the time when it was built.

Two problems—when was Baalbek built and who was its builder, and

where was Dan and what was the fate of its temple—have a common

answer.

The tradition as to the age of the acropolis and temple area of

Baalbek is not wrong. Only a few years after Solomon’s death the

house of the high places of Dan-Baalbek was built by Jeroboam.*

Possibly, Solomon had already built a chapel for the oracle, besides

the palace for his Egyptian wife.

The Djenoun who, according to Arab tradition, built Baalbek for

Solomon were apparently the tribesmen of Dan. In the Hebrew

tradition, too, the tribesmen of Dan, because of the type of worship

in their capital, were regarded as evil spirits.

In the corrupted

name of Delebore, who, according to Macrobius, was the king who

built Baalbek and introduced there the cult of Heliopolis from

Egypt, it is possible to recognize the name of Jeroboam who actually

returned from Egypt before he built “the house of the high places”.

EDITORIAL

POSTSCRIPT

Velikovsky’s essay on Baalbek was

planned to include a discussion of the names by which this place

was known in Egyptian texts. This part was not written, but a

few notes of his, scattered among his papers, may help us to

follow his reasoning. One note reads:

“Dunip (Tunip) of the el-Amarna

letters and other ancient sources was Dan. It was also

Kadesh of Seti’s conquest. Finally, the place is known as

Yenoam (’Yahwe

speaks’) which refers to the oracle.”

Tunip: As Velikovsky noted in

“From the End of the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Time of Ramses

II” (KRONOS III.:3, p. 32) certain scholars (e.g., Gauthier)

have identified Tunip with Baalbek, though others (e.g., Astour)

have disputed the link.

Thutmose III recorded the capture of

Tunip in the 29th year of his reign; an inscription

recounts the Egyptian king’s entering the chamber of offerings

and making sacrifices of oxen, calves, etc. toAmon and Harmachis.

The el-Amarna letters indicate that the same gods were

worshipped at Tunip as in Egypt.

On the walls of a Theban tomb of the time of Thutmose III (that

of Menkheperre-Seneb), among paintings of foreigners of various

nations, there is one of a personage from Tunip, carrying a

child in his arms. Velikovsky thought that, possibly, it was a

depletion of Jeroboam, and that the painting illustrated the

passage in the First Book of Kings (II :40):

“And Jeroboam arose, and fled

into Egypt, unto Shishak, king of Egypt...”

Among the considerations which led

Velikovsky to identify Tunip with Dan-Baalbek were,

(1) Tunip was located in

the general area of Baalbek, with some scholars asserting

that the two were one and the same.

(2) There was a temple of

Amon at Tunip; the Roman equivalent of Amon - Jupiter - was

worshipped at Baalbek.

Kadesh of Seti’s Conquest: This

identification was given in brief in Velikovsky’s article in

KRONOS III:3, mentioned above. The relevant passage reads:

“There is a mural that shows

Seti capturing a city called Kadesh. Modern scholars

recognized that this Kadesh or Temple City was not the

Kadesh mentioned in the annals of Thutmose. Whereas the

Kadesh of Thutmose was in southern Palestine, the Kadesh of

Seti was in Coele-Syria. The position of the northern city

suggested that it was Dunip, the site of an Amon temple

built in the days of Thutmose III. Dunip, in its turn, was

identified with Baalbek.”

Pseudo-Hippolytus (Sermo in Sancta

Theophania in J.P. Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus [Graeca]

Vol. 10, col. 705) gives the information that Manasseh, son of

Hezekiah, restored Baalbek. In his forthcoming Assyrian

Conquest, Velikovsky suggests that this could have been a reward

for Manasseh for his “loyalty to the Assyrian-Egyptian axis”.

Yenoam: Regarding Yenoam, I find only the following among

Velikovsky’s notes:

“Yenoam-Dan (Yehu probably

introduced the cult of Yahwe at Dan).”

Yenoam, read in Hebrew, could be

interpreted as “Ye [Yahwe]

speaks”; Velikovsky evidently saw in the name a reference to the

oracle at Dan.

Yenoam is mentioned among the towns

taken by Thutmose III (he captured it soon after taking Megiddoj.

In the el-Amarna letter no. 197 there is a reference to a town

named Yanuammu. Later, Seti recorded the despatching of an army

against Yenoam, in the first year ofhis reign. Yenoam is once

again mentioned on Merneptah’s so-called Israel Stele; the claim

is that it was “made non-existent.” In Ramses II and His Time

this deed is ascribed to Nebuchadnezzar.

- Jan Sammer

References

-

I Kings 11:27, 28.

-

I Kings 12:26, 27.

-

I Kings 12:28, 29.

-

I Kings 12:32. 33.

-

I Kings 12:28.

-

I Kings 12:30.

-

I Kings 12:31.

-

II Kings 23: 15.

-

Judges 20:1; I Samuel 3:20.

-

See Israel Exploration Journal,

Vol. 16 (1966), pp. 144-145; ibid., vol. 19 (1969), pp.

121-123. [In 1980, an arched city gate was reportedly

uncovered at this site. - LER]

-

Anriquities V.3.i.

-

Similarly, the passage in the

Book of Enoch (13:7), which refers to Dan to the “south of

the western side of Hermon” must not be treated as an

historical location.

-

Numbers 13:21.

-

Numbers 34:3,7-8.

-

Judges 18:27-29.

-

Judges5:17.

-

Judges 18:30.

-

Judges 18:1.

-

Judges 17:4, 7-13.

-

Judges 18:30.

-

Samuel 24:6.

-

Kings 15:20.

-

Amos 8: 14.

-

I Kings 12:30.

-

Hosea 4:15.

-

Hosea 10:5.

-

Joshua 7:2; cf. Joshua 18:11-12:

“and the lot . . . of Benjamin . . . and their border . . .

at the wilderness of Beth-Aven.” Cf. also I Samuel 13:5 and

14:23.

-

Hosea 10:18.

-

I Kings 12:28-30.

-

Amos 1:5.

-

Jeremiah 4:15.

-

Robert Wood, The Ruins of

Palmyra and Baalbek (Royal Geographical Society, London,

1827), Vol. Ill, p. 58; first published as The Ruinen of

Baalbec (1757).

-

“Wir wissen aussert wenig von

dem Schicksal Baalbeks in Altertum”, O. Puchstein, Führer

durch die Ruinen von Baalbek (Berlin, 1905), pp. 3-4.

-

“Es war leider bei den an

glanzenden Erfolgen so reichen Ausgrabungen eine

Enttauschung, dass sie uber das Wesen des Gottes und die

Geschichte seiner Verehrung nichts gelehrt hat.” H.

Winnefeld, Baalbek, Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen und

Untersuchungen von 1895-1905, ed. by Th. Wiegand, Vol. II

(Berlin, 1923), p. 110.

-

C. F. Volney, Voyage en Syrie et

en Egypte, pendent les années 1783-1785 (Paris, 1787), p.

224.

-

Idrisi in P. Jaubert, Geographie

d’Edrisi (Paris, 1836-1840), I, p. 353; quoted by C. Ritter,

Die Erdkunde, Vol. XVII (Berlin, 1854), p. 224.

-

Al-Qazwini Zakariya ibn

Muhammad, Kosmographie, H. F. Wüstenfeld ed. (Berlin,

1848-49), II, p. 104.

-

A. Asher tr. and ed.. The

Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela (N.Y. 1840-41).

-

R.Wood, TheRuins of Palmyran

Baalbek (London, 1827),p.58.

-

C. F. Volney, op. cit., p. 224.

-

E. Robinson, Biblical Researches

in Palestine and the Adjacent Regions (London, 1874), Vol.

Ill, pp. 519-520.

-

Lucian, De Dea Syria, par. 5;

Macrobius, Saturnalia I. 23: Assyrii quoque Solem sub nomine

Jovis, quem Dia Heliopoliten cognominant, maximis ceremoniis

in civitate, que Heliopolis nuncupatur. Ejus dei simulacrum

sumtum est de oppido Aegypti, quod et ipsum Heliopolis

apellatur, regnante apud Aegyptios Senemure; perlatum est

primum in eam per Opiam, legatum Deleboris, regis Assyriorum,

sacerdotesque Aegyptios, quorum princeps fuit Partemetis,

diuque habitum apud Assyrios, postea Heliopolim commigravit.

-

Hosea 10:5.

-

Hosea 10:8.

-

Judges 18:28.

-

I Kings 9:17-18.

-

Joshua 19:44.

-

Michaelis, Supplementa ad lexica

hebraica (Gottingen, 1784-1792), pp. 197-201; Ritter, Die

Erdkunde, Vol. XVII, pp. 229-230; E. F. C. Rosenmüller, The

Biblical Geography of Asia Minor, Phoenicia and Arabia,

tr.by N. Morren (Edinburgh, 1841), 1. ii., pp. 280-281; W.

H. Thomson, “Baalbek” in Encyclopaedia Britannica (14th

ed.), Vol. II, p. 835.

-

Joshua ll:17;cf. St. Jerome,

Onomastica, article “Baalgad”.

-

E. Meyer, Geschichte des

Alterthums, Vol. I (first ed., Berlin, 1884), p. 364, note;

Robinson, Biblical Researches, III, p. 410, n. 2.

-

Cf. Robinson, Biblical

Researches, III, p. 519; Ritter, Die Erdkunde Vol. XVII, pp.

229-230.

-

Song of Songs 8:11.

-

G. H. von Schubert, Reise in das

Morgenland in den Jahren 1836 und 1837 (Erlangen, 1838,

1839); Wilson, Lands of the Bible, Vol. II, p. 384.

-

O. Eissfeldt, Tempel und Kulte

syrischer Stadte in hellenistischromischer Zeit (Leipzig,

1941), p. 58.

-

F. H. W. Gesenius, Thesaurus

philologicus linguae hebraeae et chaldeae Veteris Testamenti

(Leipzig, 1829), p. 264.

-

Michaelis, Supplementa ad lexica

hebraica, p. 201; Rosenmüller, Biblical Geography, I. ii, p.

281, Wilson, Lands of the Bible, II, p. 384.

-

Herodotus, Histories II. 42;

Diodorus Siculus 1.13.2.

-

G. Hoffman, “Aramäische

Inschliften.’’Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, XI (1896), p.

246.

-

See the recent discussion by

Jean-Pierre Adam, “À propos du trilithon de Baalbek, Le

transport et la mise à l’oeuvre des mégalithes,” Syria LIV

(1977), pp. 31-63.

-

O. von Richter, Wallfahrt, p.

88; quoted by Ritter, Die Erdkunde, XVII, p. 231.

-

S. Wolcott, “Notices of

Jerusalem; and Excursion to Hebron and Sebeh or Masada; and

Journey from Jerusalem northwards to Beirut, etc.” in

Bibliotheca Sacra (1843), p. 82; quoted by Ritter, Die

Erdkunde, XVII, p. 232.

-

See von Schubert, Reise in das

Morgenland, op. cit.. Vol. III, p. 325.

-

Chronographia in Corpus

Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae 11, p. 280.

-

Robinson, Biblical Researches,

III, p. 509.

-

Robinson suggested that

“Antonine rebuilt the great temple of the Sun: and erected

the lesser temple to Jupiter Baal” (Biblical Researches,

III, p. 520, n.6).

-

O. Puchstein in Th.Wiegand ed.

Palmyra (Berlin, 1932).

-

B. Schulz in Wiegand ed.,

Palmyra

-

H. Winnefeld, B. Schulz, Baalbek

(Berlin, Leipzig, 1921, 1923).

-

L. Ginzberg, Legends of the Jews

(Philadelphia, 1928), VI, p. 375.

-

Winnefeld in Wiegand,Baalbek,

op. cit., Vol. II (1923), p. 110:

-

Rene Dussaud, “Jupiter

heliopolitain,” Syria 1 (1920), pp. 3-15; Nina Jidejian,

Baalbek Heliopolis “City of the Sun” (Beirut, 1975), ill.

no. 135-140.

-

Sat. i. 23. 12.

-

Jeremiah 4:15.

-

Pesahim 117a; see Ginzberg,

Legends of the Sews, VI, p. 375.

-

The readers of this passage

probably understood it in the sense that Micah’s oracular

image, after being removed from the temple of Dan, was

placed in Baalbek. Baalbek being Dan, such an interpretation

is superfluous.

-

|