|

by Warren Aston

July 14,

2020

from

Popular-Archaeology Website

PDF format

|

Warren Aston is an independent researcher

based in

Brisbane, Australia.

He

studied archaeology at the University of Queensland, and

has been involved in archaeological projects in Mexico

and Oman over several decades.

He

can be reached at:

astonwarren@hotmail.com |

Over

400 mounds on New Caledonia in the southwest Pacific may

mark a human presence predating the current earliest

generally accepted dates by thousands of years.

The following paper, relates a detailed review of the

investigation of enigmatic tumuli, or mounds, on the

Isle of Pines, part of the island French territory of

New Caledonia in the South Pacific.

The

origin and purpose of these tumuli have eluded

investigators and scientists for decades, sparking

various conjectural explanations for their existence.

If

the tumuli represent the work of humans, they would

provide evidence for human occupation of the island

thousands of years before the currently accepted dates

for human habitation.

The

author suggests a new hypothesis for further study.

RECOVERING A

PRIMAL EVENT IN SOUTH PACIFIC PREHISTORY

NEW CALEDONIA'S TUMULI - TOWARD

RESOLUTION

The ancient migrations settling the South Pacific remain poorly

understood.

This is particularly so

when the New Caledonia sequence is considered and where perhaps the

greatest archaeological mystery of the region awaits resolution.

Scattered across the

Isle of Pines

more than 400 tumuli, or mounds, shelter substantial cement

blocks, many with a circular shaft running through their centre.

The only tumulus fully

excavated also revealed a large cone-shaped iron object buried

directly beneath the shaft, function unknown.

Described by two

archaeologists as recently as 2015 as "a kind of archaeological

nightmare" 1 the origin and purpose of the tumuli remains

enigmatic, the mystery compounded by studies revealing dating

thousands of years earlier than settlement models currently allow.

The paper outlines

various investigations over the last century before arguing that

excavation data from two seminal studies (Chevalier 1963 and Lagarde

2017) demonstrate that non-anthropic explanations - notably the

long-standing avian theory - fail to address the substantial data

indicating a human presence on the island predating the Early Modern

Era.

A new hypothesis for the

original purpose of the tumuli is presented, one based on the

accumulated data.

NOMENCLATURE

While the term "tumulus" - a mound - is accurate enough, the word

can have an unfortunate association in English with burial

practices.

To remove the ambiguity

provided by the fact that there are, of course, numerous other

"mounds" of varying characteristics, both on the Isle of Pines and

elsewhere, the term "tumulus" in this paper refers to what are more

accurately described as a "cement-core tumulus."

The cement interior of the tumuli is typically referred to as a

"cylinder" in the various early reports.

As this term conveys the

implication of circularity, and these structures are actually

cube-shaped, this paper will use the term "core" as more accurate

terminology.

INTRODUCTION

The

Melanesian Kanak population is

believed to have inhabited the islands of New Caledonia since the

so-called Lapita period around 1350 BC.

The first European

arrivals on Kunie, the Isle of Pines, in the early nineteenth

century noted the numerous tumuli, but the indigenous population

ascribed no particular significance to them.

This led to some early

investigations and conjecture, but no sustained attention for many

decades.

Proper studies and

initial excavations commenced only in 1959. Since then, scholarly

opinion has advanced - and discarded - a range of ideas concerning

the tumuli, but without a consensus to the present.

MATERIAL

REMAINS - A DESCRIPTION

More than 400 large tumuli are dotted over much of the Isle of Pines

with a concentration on the central so-called "Iron Plateau," plus

about 20 at particular locations in the south of the main island of

New Caledonia.

No systematic attempt has

yet been made to locate tumuli elsewhere on the main island or,

indeed, the other islands of the group.

Early settlers assumed

these were simply ancient burial mounds, but no graves, bones,

pottery, charcoal, etc. have ever been found in them.

The locations of the tumuli generally appear to be quite random

regardless of the terrain, although in a very few places a possible

alignment or circle might be perceived in aerial images. More

certain is the fact that most tumuli are rarely spaced less than 200

m apart, as geologist Jacques Avias noted in 1949. 2

The tumuli average about

3 m in height with a circumference ranging between 15-25 m. 3

While the majority of

tumuli fall into this size range, a handful of oval shaped

structures have also been described; one that was examined measured

3 m high and 16 m wide. 4

New investigations have revealed that as much lies beneath the

tumuli as above; the mounds contain a large square or oblong core

made of a high-grade concrete. The most detailed excavation to date

of a tumulus was on the Isle of Pines in 1959, revealing a core

almost 2.60 m tall and a substantial 1.8 m across.

At several points along

the height of the core it was encircled by rings of iron-oxide

nodules. 5

The oval-shaped tumulus

noted earlier proved to have two concrete cores, each 2 m diameter,

and placed 5 m apart. 6 While the concrete cores so far

examined appear to consist of homogenous material, the upper part of

one of the Paita cores that was completely demolished contained

irregular pockets of soil of varying sizes. 7

With regard to the soil

intrusions, excavation data remain too limited to draw any

conclusions.

Most intriguingly, the Isle of Pines tumulus excavated by Chevalier

in 1959 revealed that buried directly below the centre of the core

was a symmetrical cone or top-shaped iron object, pointing down and

surrounded by 3 rings of large iron nuggets.

It was over 2 meters

long... 8

As will later be

discussed, Chevalier's excavations of two tumuli at Paita also

revealed puzzling features below the concrete core. One of the

tumuli completely demolished on Paita revealed a separate "vaguely

circular" slab of cement beneath it, in the middle of which was a

wide (90 cm) and deep (1.8 m) trench, oriented east-west, and two

holes at different depths.

The other Paita tumulus

did not appear to have a comparable feature beneath the core. 9

Another, most significant, feature was not noted until the

excavations led by Jack Golson in 1959-1960: a circular, vertical,

shaft running from the top of the core at its centre down to its

base; this will be discussed further.

Figure 1:

Known tumuli locations

on the Isle of Pines

(after D. Frimigacci, Notice explicative de la feuille Ile des Pins:

Carte géologique à l'échelle, Paris: BRGM, 1986, 28).

Figure 2A:

One of hundreds of enigmatic "tumuli" on the Isle of Pines.

This early photograph was published by R. H. Compton in 1917

and shows one of the rare double-cored mounds.

Figure 2B:

A 1949 aerial view of the "Iron Plateau" of the Isle of Pines

with scores of tumuli visible before reforestation of the area.

Figure 3:

Today,

hundreds of mounds lie in open land

or in pine forests on the Isle of Pines.

Photograph by the author, 2017.

MODERNS

ENCOUNTER AN ENIGMA

Some of the underlying issues for some aspects of New Caledonian

and, more generally, for South Pacific pre-history remaining in

somewhat of a stalemate were discussed in Roger Green & J. S.

Mitchell's 1983 paper, "New Caledonian Culture History: A Review of

the Archaeological Sequence." 10

The authors provide the

following reasons:

-

firstly, over the

years research has appeared in a great range of venues and

is seldom integrated.

-

secondly, not all

findings have been published in readily available sources

(and sometimes not published at all)

-

thirdly, a

perceived language barrier as the main sources are

[obviously] in French and English

-

finally, one of

the primary sources (Gifford & Shutler, 1956) has some

deficiencies in its presentation of data - something Green

and Mitchel discuss - and investigators since have not

followed a consistent terminology or frame of reference

A chronological

examination of the main sources reveals the long-standing confusion

over how to account for the tumuli within the accepted time-frame of

human arrival in New Caledonia, as well as the factors outlined by

Green and Mitchell just noted.

To examine even a brief

history of modern sciences' attempt to understand these structures

is to encounter a spectrum of human foibles, ranging from honest

reporting with rational analysis to degrees of disingenuity and,

above all, avoidance.

Early observers on the Isle of Pines realized that these scattered

mounds represented a mystery and were quick to seek answers.

As early as 1897,

Frenchman Theophile-Auguste Mialaret reported "opening" a

tumulus, but finding nothing of interest. 11

In 1917, Englishman

R.H. Compton reported in The Geographical Journal the

"remarkable" dome-shaped mounds of earth:

"…excavation has

revealed no contents of interest…various suggestions have been

put forward to explain them."

In both cases their

efforts were watched, as Compton noted,

"without fear by the

indigenous people who, while claiming that they did not make the

tumuli, could give no explanation for their origin."

He concluded:

"I am quite unable to

offer any suggestion as to their origin myself." 12

The 1949 paper by Avias

included an aerial photo (reproduced here as Figure 2B) showing

"nearly two hundred" tumuli on the central "Iron Plateau."

He proposed a series of

ancient arrivals in the southern Pacific, predating the Melanesians,

,

"…at least the

following hypothesis can be put forward: a civilization…

preceded the present Kanak civilization… this civilization had a

Neolithic industry more advanced than the indigenous people."

13

That the structures

contained a massive concrete core remained unsuspected and unknown

until proper excavations on the Isle of Pines began in 1959.

Leading the post-war

vanguard of serious investigators were two archaeologists, Jack

Golson and Luc Chevalier.

From 1959-1960 British-born Australian archaeologist Jack Golson led

a team excavating four "tumuli" on the Isle of Pines, finding that

there were at least 3 types of structures.

Golson's team went on to

map more than 120 mounds and excavated three of them. They viewed

the concrete cores as "anchors" and established, by probing their

centers, that "many" other mounds also had a cement core.

As briefly noted earlier,

their excavations revealed that at least several of the cores had a

vertical hole running through them, a feature they termed

"postholes," but could not determine what function the shaft might

serve.

Golson published a brief report in 1961, "Report on New Zealand,

Western Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Fiji" concluding:

"The mystery of the

tumuli is thus, despite this spate of activity, as great as

ever. Who were these concrete makers of New Caledonia and what

is the function of their constructions?

Native tradition is

silent and the archaeologist as yet ignorant." 14

In 1963 he published more

data from his expedition in "Rapport sur les fouilles effectuees a

l'ile des Pins (Nouvelle Caledonie) de Decembre 1959 li Fevrier

1960" and with Daniel Frimigacci in 1986, "Tout Ce Que Vous Pouvez

Savoir Sur Les Tumulus, Meme Si Vous Osez Le Demander,'' 15

providing a comprehensive summary of the topic.

Luc Chevalier, the French archaeologist, was led by unexpected

circumstances in September 1959 to shed further light on the tumuli.

Based in

Noumea as curator of the National

Museum, Chevalier traveled to the Isle of Pines to investigate a

report that local workers upgrading a road had encountered a solid

white "rock" at the centre of a tumulus they were demolishing for

road-building material.

With a half-exposed mound

as a starting point, Chevalier immediately began excavating until

the southern side of the tumulus core was exposed and the unexpected

object beneath it revealed.

Chevalier describes it as

an "iron oxide rock" about 2.40 m tall - almost as tall as the core

itself - and a maximum diameter of 1.10 m, resembling a symmetrical

upside-down "top" or cone, pointing down.

At that point, the entire

structure threatened to collapse; amid several small landslides

excavation was halted.

In 1963, Chevalier's

final report, "Le Probleme des Tumuli en Nouvelle-Caledonie"

appeared in the Bulletin de la Societe des Etudes Melanesiennes;

16 It deserves close reading.

Figure 4A, 4B (2 images):

The exposed 2 meter high concrete core

from the tumulus excavated by Chevalier in 1959,

with a close-up view of large iron nodules

embedded in it.

Photographs by the author, 2018.

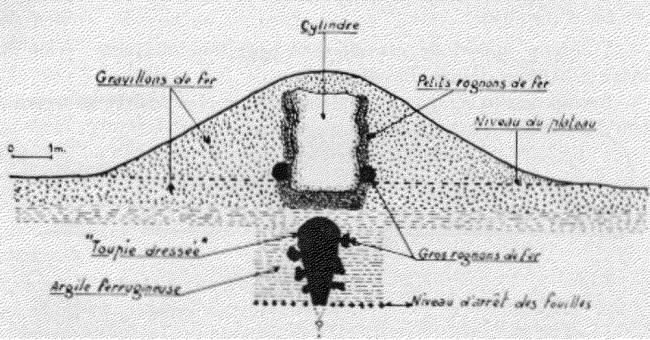

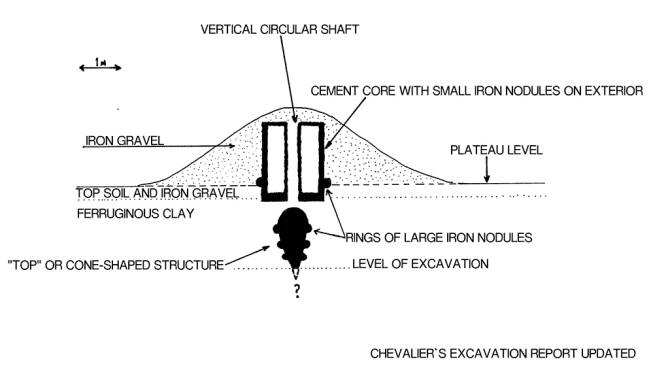

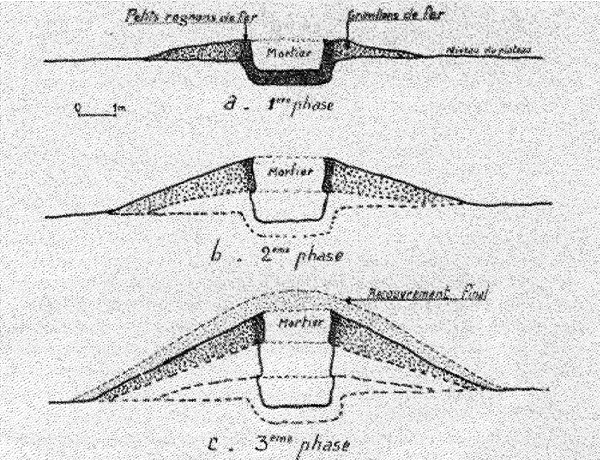

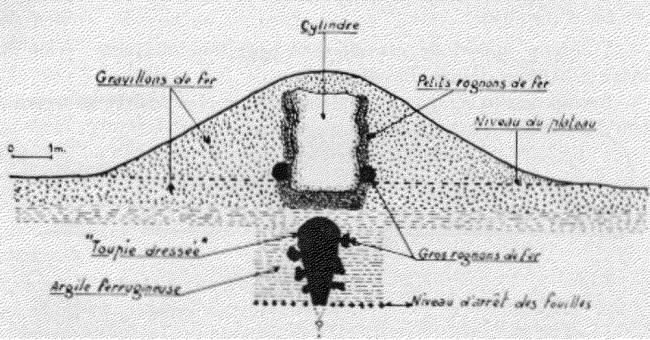

Figure 5:

Chevalier's 1963 excavation report (his Fig. 5)

shows the interior of the mound after excavation.

The rings of iron nodules and the top-shaped object

buried beneath the central core are clearly shown.

Chevalier then examined

other nearby tumuli on the Iron Plateau, determining that at least

many of them also contained a central core made of "white mortar"

and making particular note of the oval-shaped tumulus that contained

two cores.

Returning to Noumea, he

then investigated several tumuli in the region of Paita just north

of the capital.

An identical situation to

what had happened on the Isle of Pines involving road workers was

replicated in Paita; this time uncovering two concrete-cored tumuli

about 300 m apart.

It was here that several

intact Placostylus snail shells found embedded in the concrete

matrix of the cores and were sent, with samples of the cement, to a

laboratory in Paris for dating.

His report shows images

of the exposed concrete cores of 2 of the Paita tumuli being

demolished.

Despite anticipating further excavations that would "verify the

presence and shape of this [cone-shaped] stone under the other

tumuli," 17 Chevalier's next excavations at Paita would

only raise more questions.

Aside from the absence of

any mention of Golson's "post holes" in the concrete cores (about

which Chevalier may not have been aware) in his reports, those he

examined remained completely analogous to those in the Isle of Pines

tumuli although, as noted earlier, the Paita cores had differing

material beneath them and the cone-shaped object was not found in

these part-excavations.

Nor does Chevalier

mention returning to the Isle of Pines, although he expressed

optimism that a complete excavation campaign there would be possible

the following year, ie. 1960. 18

Among other significant aspects, Chevalier noted that on both the

Isle of Pines and at Paita the excavations were culturally sterile;

that is, no tools, pottery, charcoal etc. could be found.

The closest thing to a

cultural artifact was the apparent surplus of construction materials

found near the two Paita tumuli excavated, a quantity of lime mortar

mixed with silica near one and a 10 m wide elevation of silica

gravel near the other.

Both offered clear

indications of human involvement likely, as Chevalier recorded,

being the places where cement was prepared before being poured into

the centre of the tumulus to form the core. 19

He commented,

"There is no doubt

that the same people who made the tumuli on the Isle of Pines

also made those in the region of Païta.

The only difference

between them is that the tumuli of Païta are made of a supply of

silica present everywhere, while those on the Island of Pines

used the "iron shot" which is found in abundance on the plateau…

It is also necessary

to determine the origin of most of the mortar: or is this the

result of the calcination of coral?… it is curious to find no

fragments of charcoal in the mortar.

[It indicates] a

space between the time of the construction of the tumuli and the

pre-European Melanesian era."

The conclusion of his

report "Many Questions Without Answers," summed up the facts:

"The tumuli of New

Caledonia are undoubtedly the result of an ancient human

activity of which there is no trace in the local tradition.

Remember that the

manufacture and use of lime was not known to the natives before

the arrival of the missionaries in 1843.

One is perplexed by

the importance of the work done to erect these monuments. When

one thinks that a tumulus represents on average, a volume of 200

m3 and that on the Isle of Pines alone there are more than 300

tumuli, requiring a very large workforce.

However, this

workforce during its work, had to leave some traces of its

passage, its life, its activities… to date, no trace, no

evidence, no vestige, either inside or outside the tumulus has

been found."

Chevalier closed with the

following, very perceptive, observation:

"…a final question

arises in our mind: the builders of these tumuli knew perfectly

the principle of manufacturing and using the mortar for the

erection of the cylinder.

Why did they not use

this knowledge for other works, other realizations, their

dwellings, for example…?

Would they have

reserved this knowledge only for the tumuli, conferring to these

monuments a particular character, even a sacred one?"

Had more attention been

given to these questions by those who came after Luc Chevalier, our

understanding of these structures would have advanced more rapidly

than it has and without the avoidance of facts and obfuscation in so

much of the commentary since then.

DATING

The results of two chemical analyses of the components of the

concrete (one from the Isle of Pines, one from a Paita tumulus)

appeared in Chevalier's 1963 report and are quite comparable.

The primary disparity

evident in the Fe and Si amounts reflecting the two very different

environments of origin.

The dating of the mortar

and snail shells from a core excavated on Paita by Chevalier was

published in a 1966 paper in Radiocarbon. This gave radiocarbon

dates for surface and interior mortar (7070 ± 350 and 9600 ± 400 BP

respectively), plus a date for Placostylus snail shells on the

surface of a cylinder (12,900 ± 450 BP).

Echoing Chevalier's

belief that the tumuli "testify to an important human activity

completely extinct today…" the report's authors noted that if the

cores were really man-made "…they are by far the most ancient

mortars known." 22

Radiocarbon dating by

others since have served to confirm Chevalier's very early dates.

For example, a 1972

dating of tumulus cement yielded ages ranging from 4120 ± 90 to 7710

± 70 BP. 21

Space constraints prevent a full review here of those who have

accepted this dating, but they include scholars such as,

-

Brookfield & Hart

in 1971, 22 Fr. Marie-Joseph Dubois (1976)

23

-

Richard Shutler

Jr. (1978) 24

-

Peter Bellwood

(1978) 25

-

Roger Green & J.

S. Mitchell (1983) 26

-

Kerry Ross Howe

(1984) 27

-

John R. H.

Gibbons & Fergus G. A. U. Clunie (1986) 28

-

Christophe Sand

(1999) 29 and Patrick V. Kirch (2000 and 2017)

30

It is an understatement

to say that the disconnect between the Placostylus and mortar dating

and the conventional understanding of human settlement in the

Pacific is unbridgeable.

To contemplate people

arriving in New Caledonia as early as 12,000 years ago simply cannot

be massaged into the accepted scenario.

Consequently, many -

perhaps most - of these researchers believed that the

extraordinarily early snail shell dating had probably been of much

earlier material, thus allowing for the actual tumulus construction

to have taken place perhaps in the Lapita period, roughly 1500 to

500 BC.

Other commentators simply

ignored these data.

No-one seems to have

asked how multiple fragile snail shells survived intact for many

thousands of years before finding their way onto the outside of a

block of drying cement, for the shells were found on the surface of

the cement, not in its interior.

One shell can be clearly

seen in Fig. 14 of Chevalier's report.

EXOTIC

EXPLANATIONS 1949

Unsurprisingly, the inability of archaeology over many years to

provide resolution as to the origins of the tumuli led to several

proposals far from main-stream thinking.

This began as early as

1949 with the "working hypothesis" of Jacques Avias already noted.

After attempting in vain

to locate patterns in the placement of the tumuli and any

correspondences to the southern constellations Avias broadened his

studies to all other traces from the past, such as petroglyphs and

pottery styles across New Caledonia.

His paper offered

suggestions that a Neolithic culture predating the present Kanak

civilization may have been influenced by, or even originated in,

certain Eastern cultures, specifically the Chinese and Japanese.

He developed an earlier

thought expressed by P. Rivet in 1931 that from Japan the Ainu may

have explored the Pacific islands. 31

While not subscribing to

such views themselves, Daniel Frimigaccci and Jack Golson also

mentioned that ,

"most extreme

hypotheses were advanced to explain their presence [the

tumuli]," noting in particular "extraterrestrials or mysterious

populations now extinct practicing stellar-solar rites." 32

One of the great ironies

is that attempts to explain the tumuli by invoking incursions by

distant explorers, inhabitants of the legendary continents of

Mu,

Atlantis or the Aroi Sun Kingdom,

33 or extraterrestrials, 34 now appear

somewhat less fanciful than they once seemed, especially when more

prosaic explanations are compared.

This is no more so than

the avian theory to be discussed next.

THE "AVIAN"

THEORY 1985

In late 1985, after bones of an extinct Megapode bird species were

found in New Caledonia, Cecile Mourer-Chauvire and

Francois Poplin published "Le Mystere de Tumulus de Nouvelle-Caledonie,"

35 proposing that these birds may have formed each

tumulus by scraping the ferritic soil into a giant mound in which

the eggs could be deposited and incubated until hatched.

Left unexplained was how

this process somehow produced a massive, linear, block of cement in

the interior, with a hole running through it and, in at least one

case, a large cone-shaped iron structure buried directly below that.

They concluded that,

"the giant bird

hypothesis is just as reasonable as the theory that these mounds

were built by ancient humans who knew how to make cement."

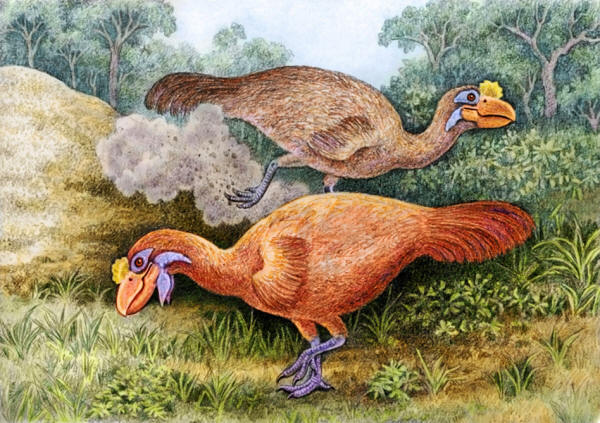

Figure 6:

The conjectured formation of the tumuli

by the large extinct bird Sylviornis neocaledoniae,

seen here scraping soil into a mound for nesting.

From this quite cautious proposal, the idea caught hold. Notably,

since his 1983 co-authored paper listed earlier, archaeologist

Roger Green came to accept this naturalistic explanation for the

mounds as outlined in his influential 1988 article, "Those

mysterious mounds are for the birds." 36

Green's article gives

good background of how the Megapode theory was first pressed into

service to explain the mounds.

That redeeming feature

aside, the reader needs to take some giant leaps of faith:

the concrete cores

are explained away as the wholly natural action of

microorganisms, tiny globules of calcite in the soil somehow

binding rocks and debris together.

Later on, it was proposed

that the nesting birds also introduced vegetation into the mounds

which decayed, providing heat for the eggs.

Subsequently, a

refinement of the theory proposed that the Megapode tidily excreted

into the hole in the top of the mound, the feces becoming the

heating agent for the eggs.

Over time, the droppings

are presumed to have fossilized and become the "cement" found today.

The Megapode theory failed to account for what qualified

archaeologists actually found in the tumuli: the components of the

concrete and the iron artifacts around and beneath the core.

It typically did not

concern its proponents that no trace of bird shell or other material

that would normally indicate an avian presence had been found.

Of course, not all scholars accepted the avian theory. Some

indicated their tacit acceptance of an anthropic origin for the

tumuli, sometimes in regard to the political implications any notion

of pre-Melanesian settlement presents.

See, for example, John

Connell, "New Caledonia or Kanaky? The political history of a

French colony." 37

Others remained open to a

human origin for the tumuli without taking a firm position pro et

con.

A 1995 paper by

Janelle Stevenson and John R. Dodson was open to earlier

arrivals, noting the evidence for human occupation 28,000 years ago

on Buka Island in the nearby Solomons.

They noted the divided

opinions on the mounds, stating that "no cultural material or bird

remains" had been found, but avoided any direct mention of the

cores. 38

In 1999, Stevenson noted

that human arrivals earlier than the Lapita culture (ca. 3200 years

ago), would remain speculative,

"…as long as a human

origin for the so-called tumuli of New Caledonia is

entertained…" referencing a paper by Christophe Sand. 39

A 1997 review by

Patrick V. Kirch of three 1995 publications by Christophe

Sand (until 2019 Director of the Institute of Archaeology of New

Caledonia and the Pacific in Noumea), critiqued the multiple earlier

scholars whose analysis of data suggested the "specter" of an

aceramic, cultural, origin.

Sand's publications were

also criticized for not adequately discussing the Megapode theory.

40

Kirch essentially

maintained his pro-avian position throughout his 2000 book On the

Road of the Winds - An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands

Before European Contact.

It was republished in

revised form in 2017, but while he accepted tumuli dating as early

as "10,950 BC" it continued the inaccurate (and unreferenced)

assertion that "egg shell" had been found in "the mounds." 41

The avian theory continued to be uncritically accepted when it

reinforced more general positions. A representative statement from

anthropologist Susan O'Connor argued in 2010 against the 1986

Gibbons & Clunie proposal for Pleistocene voyaging between the

eastern edge of the Australian continent and New Caledonia.

Their two primary

arguments for the voyaging rested on the reduced distances needed

for ocean crossings when sea levels were lower and the reported

human derivation of a series of ‘tumuli' or artificial mounds on the

interior plateau of the Isle of Pines.

O'Connor's comment

regarding the tumuli,

"was that they dated

to c. 12,000 BP, [and] have been shown as built by megapodes."

42

Beginning as a

well-intentioned attempt at explanation, for many the "megapode"

theory became a convenience to avoid dealing with the possibility of

a pre-Lapita human presence.

But it was a fiction all

the same. After all, the actual components of the cement cores have

been known since Golson and Chevalier's work was published and,

along with other items we would expect if birds were involved,

neither Phosphorous nor any fragments of egg shells have been found

in the tumuli.

The avian theory was dealt its final fatal blow on 30 March 2016

with publication of a paper by Trevor H. Worthy et al. titled

"Osteology Supports a Stem-Galliform Affinity for the Giant Extinct

Flightless Bird Sylviornis neocaledoniae (Sylviornithidae,

Galloanseres)," in PLOS ONE. 43

Significantly, Christophe

Sand was a co-author.

Page 53 of the paper

discusses the avian explanation for the tumuli:

Sylviornis

neocaledoniae has been identified as a possible maker of large

mounds or tumulion La Grande Terre and Ile des Pins.

However, there is no

evidence of association of this species with these mounds and

eggshell has not been found in them, despite the calcareous

nature of at least those on Ile des Pins.

Given that our analyses

show that S. neocaledoniae has no enhanced morphological adaptations

for digging, such as those displayed by certain megapodes, it is

most unlikely that it is responsible for these tumuli.

Instead these tumuli are likely to be formed by an interplay of

vegetation and erosion as suggested for similar mounds elsewhere.

Even if mounds were

associated with eggshell, then the largest of all Megapodius

species, the New Caledonian endemic and extinct M. molistructor

Balouet and Olson, 1989 would be a more likely contender for their

builder.

The paper concluded as follows (incidentally validating the comments

made by Golson 44 in 1963 about the extinct bird under

discussion):

Our finding that it is a stem galliform (and thus not a megapode)

makes it most unlikely to have been a mound-builder, as this

scenario would require both mound-building and ectothermic

incubation to have evolved twice.

Furthermore, Sylviornis

neocaledoniae shows no specific adaptation for digging to facilitate

mound-building, unlike all extant megapodiids, making it even more

unlikely that it exhibited ectothermic incubation.

THE

"ENVIRONMENTAL" THEORY 2016

Buried within the text reproduced above lay the author's replacement

theory to explain the tumuli:

Instead these tumuli

are likely to be formed by an interplay of vegetation and

erosion as suggested for similar mounds elsewhere.

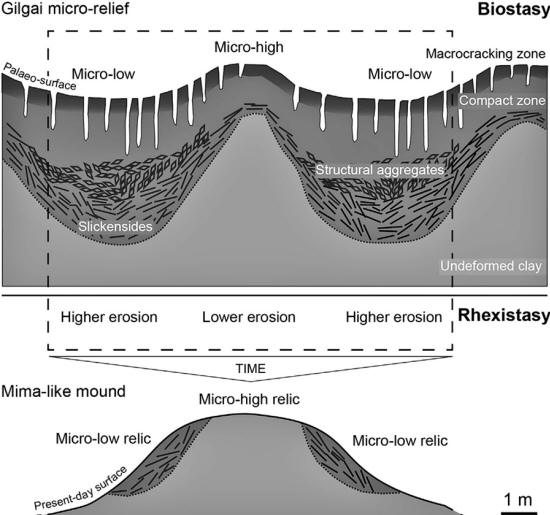

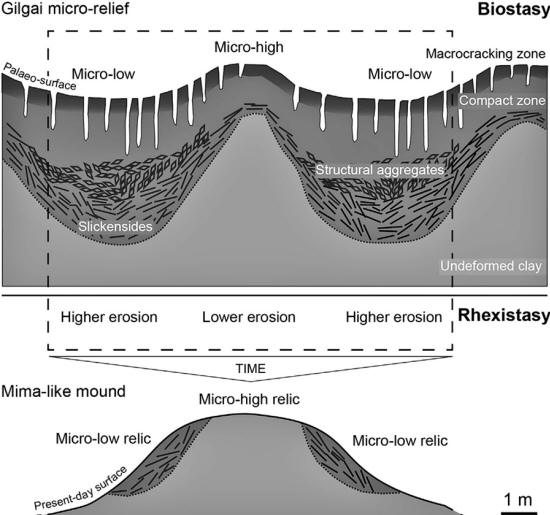

Figure 7A, 7B (2 images):

A view

showing so-called "mima-like mounds"

and a

graphic illustrating two hypothesized erosion scenarios resulting

in the

formation of mima-like mounds.

Graphic

kindly provided by Nathalie Diaz, University of Lausanne.

Can_mima-like_mounds_be_Vertisol_relics_Far_North_Region_of_Cameroon_Chad_Basin

Thus, what could be termed the "Environmental theory" was

introduced. In essence, it proposes that "calcite concretion" may

have developed around the root complex of a long rotted tree,

leading to "differential erosion" in the landscape.

Such structures are

variously known by names such as "mima-like mounds" or "heuweltjie

earth mounds" and are found in various environments around the

world.

However, an examination

of this phenomenon (including sources cited in notes 83-85) reveals

stark differences between such formations and the tumuli.

They are utterly unlike

the tumuli under discussion in this paper. Not only do the former

have smaller dimensions, but these formations lack the tumuli's

central concrete pillar, not to mention its central shaft and iron

appendages.

The suggestion is perhaps

even less plausible than the avian theory it replaces.

THE "BURIAL"

THEORY 2017

In 2008, an important development began with publication by

Frederique Valentin & Christophe Sand of a paper, "Prehistoric

Burials from New Caledonia (Southern Melanesia): A Review." 45

The paper included a

detailed description of the Tüü mound on the Isle of Pines excavated

by Daniel Frimigacci, noting that the Tüü mound likely had original

dimensions approximating the concrete-cored tumuli, but its interior

was taken up with 3 levels of human burials; a base level of loose

bones, with 2 higher levels each containing a full human skeleton.

Dating of the bones

yielded a range between 1930 and 1845 BP and appeared to be primary,

original, interments. The salient points of the text follow:

The study revealed

two stratigraphic levels containing interments (Frimigacci,

1979, pers. comm. 2000).

The lower level,

above a basal level dated to 1930+/–70 BP (UW 655, calibrated

A.D. 50 (80) 245), contained at least one complete adult

skeleton, dated to 1440 +/– 35 BP (UW 766, calibrated A.D. 560

(635) 660).

The body was on its

right side, apparently in a hyperflexed position, knees against

the chest (Frimigacci, 1979:22, figure 15).

The second level contained a complete skeleton of a male about

40 years old (Charpin, 1983). It was on its back in extension.

The surface level included many disarticulated and scattered

human bones that Frimigacci (1979) regards as representing

incomplete skeletons.

A bone sample

returned the early date of 1845 +/– 65 BP (UW 765, calibrated

A.D. 30 (160) 370).

According to Daniel

Frimigacci (1979: 21),

"ce tertre funéraire

est une sépulture collective, il a été édifié au fur et à mesure

des inhumations" [the funeral mound is a collective grave which

was built up by successive inhumations]…

The inhumations were

apparently primary and definitive, displaying variations in

positional modes and an expansion of the tumulus by addition of

sedimentary levels.

By including this description and dating for a prehistoric burial on

the Isle of Pines, the straightforward report effectively again

differentiated burial mounds from the concrete-cored tumuli (which

were left unmentioned throughout the paper).

Surprisingly, this very

description became the linchpin of another theory in 2017 when

Louis Lagarde published his paper, "Were those mysterious mounds

really for the birds?" 46

It is probably the most

important study of the tumuli published since Chevaliers 1963

report.

Positioning itself, in part at least, as a response to Roger Green's

influential argument in support of the avian theory, the paper

reviews the history of scientific enquiry into the tumuli, giving

particular credit to the pioneering work of Daniel Frimigacci in

mapping tumuli in the 1970's and also exploring the coastal burial

mounds such as the one at Tüü.

It then maps the avian

hypothesis in some detail, as well as various earlier attempts to

explain the tumuli geologically. Results of the 2006-2010 survey led

by Lagarde, some never previously published, then serve to

demonstrate why the tumuli must have an anthropic origin.

For all this material we can be grateful, but despite it the report

works up to a most unexpected detour, for notwithstanding the

long-published excavation reports and the author's own wide-ranging

experiences, the report then proposes that the burial mounds are

essentially the same as the tumuli, only the construction material

varying according to the location.

The detour is first

introduced by mentioning an oral tradition claimed by a local

informant mentioning that,

"posts were planted

on the top of earth mounds and scenes of 'torture'."

This claim had been

reported in 1986 by Frimigacci and Golson, 47 and while

Lagarde rightly warns about placing too much weight upon it, he

nevertheless uses it to introduce his primary conclusion in the

paragraph that immediately follows.

In this next discussion, Evidence of funerary practices, the dating

of a burial mound in Gadji to ca. 2309-2003 and 2208 BP is described

as "similar" to the Tüü first century AD dating; on that basis the

plateau tumuli are then declared to have the same ritual, funerary,

function as the earth mound burials.

This stunning claim

completely ignores the various carbon-dating results and, as we

shall see, the uncontested facts established in tumuli excavations.

Lagarde is careful to

first note a fundamental difference between the burial mounds and

the tumuli (one has burials, the other does not), but then

introduces the perplexing claim that the tumuli are void of any

"archaeological material":

Given this [dating]

data, it seems legitimate to suggest a new interpretation as

funerary structures for the earth mounds.

One major difference

separates the plateau structures from the coral plain ones:

in the plateau

tumuli, no evidence of archaeological material is to be

found, whereas every open tumulus of the limestone

environment (through Frimigacci's or our more recent

fieldwork) seems to contain human remains.

(Frimigacci

1986: 29)

More such claims follow:

…after sixty years of

archaeological activity on Isle of Pines, the hypothesis of an

ancient human settlement that would predate Lapita by thousands

of years should be abandoned.

Every dig and survey

campaign has only brought back evidence of material culture in

connection with already known assemblages from mainland New

Caledonia and its global, well-known, diverse cultural

traditions of the last three millennia.

…it has been impossible to discover any kind of artifact that

would indicate a pre-Lapita culture, on Grande Terre or the

Loyalty islands.

The same goes for

Isle of Pines, where no evidence of any culture that would

pre-date Lapita has ever been found, after our four-year

research campaign.

This hypothesis forces to

unite both types of tumuli in the same function, despite the lack of

archaeological evidence coming from the plateau ones.

This is however very much

in phase with the results obtained by Frimigacci.

The plateau earth mounds

and those of the calcareous seashore plain, are structurally and

morphologically identical, their differences coming only from the

environment in which they were erected.

Typologically, they are identical and linguistically, the people of

Isle of Pines call both kinds purè: furthermore they stand in

similar proportions in a population/space ratio, as hundreds of them

are to be found in both chrome and coral environments.

If one of the types was

much rarer, if language could differentiate the structures, if the

inner structure of the earth mounds was indeed typologically

different, we would have separated the tumuli into two categories.

On the contrary, we stand

confident with the hypothesis of a unique anthropogenic tradition in

which minor differences are to be explained by the surrounding

environment.

This is not our idea, as Frimigacci was the first to point out the

similarities existing between the two populations of tumuli, and to

try to explain the use of the plateau ones by the contents of the

seashore ones (Frimigacci 1986 - 32).

His archaeological

excavation of the human remains in the Tüu tumulus is for us the key

finding of the past sixty years.

Arguing at some length that human bones can completely vanish under

conditions of soil acidity and exposure to the elements via the

"tiny limestone blocks" covering the tumuli, Lagarde concludes:

…we suggest the

possibility that the tumuli are of anthropic origin, bear a

ritual/funerary function and that at least some of them were

used as funerary mounds for primary burials.

We hope to have brought

forward that the tumuli of the Isle of Pines are more

archaeologically complex than straightforward, natural, bird-made

structures.

Although being the last

pieces of evidence that could have supported the theory of a

extremely ancient human settlement of the New Caledonian

archipelago, they actually belong to the recent three millennia of

Austronesian presence.

In our opinion, they

illustrate, at least partly, the funerary practices of a time span

of five to six centuries, between the end of the first millennium BC

and the first centuries AD.

How can we reconcile

the fact that the interiors of the burial mounds and the tumuli

are, in truth, actually radically different?

What can account for

such a disconnect between the uncontested archaeological

evidence and such explanations as this report offers?

Are we seeing the

rise of a new default position to replace the discredited avian

theory?

If so, then as with all

the other attempts at explanation the tumuli it comes at the expense

of the archaeological evidence. As at the time of writing such

questions remain unresolved. 48

NEW

INVESTIGATIONS FROM 2017

The author's explorations on the Isle of Pines commenced in 2017 and

first undertook a detailed examination of the original tumulus

excavated by Chevalier.

This was to reveal that

this concrete core had a circular vertical shaft throughout its

length.

As Chevalier's excavation

report did not mention such a significant feature this unanticipated

find was initially perplexing, but it was concluded that his

excavation had not cleared the entire summit of the tumulus before

work was abruptly halted.

Thus, the opening at the

very centre of the top of the core - 1 foot/30 cm in diameter - was

missed by him.

After Chevalier returned

to the main island, local workers continued removing the mound's

iron gravel as a source of road-making material until only the

concrete core remained but the shaft would have been of little

interest even if noticed.

In fact, as already

noted, Jack Golson's 1959-1960 survey reports had mentioned this

feature in many of the tumuli he and his team had examined.

In his notes, Golson

designated the concrete cores as "anchors" and the shafts as

"postholes," but could not suggest what purpose the latter served.

49

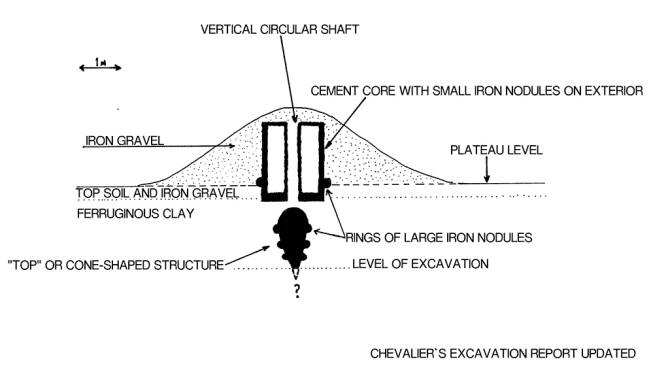

Figure 8:

Chevalier's 1963 excavation report (see Fig. 5)

redrawn with the circular shaft in the concrete core added.

Figure 9A, 9B (2 images):

Views looking down and up showing the 30 cm wide circular shaft

running vertically through the middle of the concrete core

of the tumulus excavated by Chevalier in 1959.

Photographs by the author 2018, 2020.

THE CEMENT

ANALYSIS UPDATED

From abundant large excavation debris still surrounding the tumulus,

the author obtained samples of the interior concrete and submitted

them for elemental composition analysis in an Australian laboratory.

50

Following is a comparison

of the results from Chevalier's analysis of the first tumulus

excavated on the Isle of Pines with the author's 2018 analysis of

the same structure, of the interior mortar in both cases:

Chevalier

Analysis/Author Analysis

Loss on ignition % 33.20 41.8

Fe2O3 26.57 6.6

Fe 18.60 nil recorded

Al2O3 4.00 0.4

CaO 34.25 48.2

MgO traces 0.7

SiO2 1.80 < 0.05

SO3 not recorded 0.1

MgO not recorded 0.7

K2O not recorded 0.03

Na2O not recorded < 0.05

P2O5 not recorded < 0.05

TiO2 not recorded < 0.05

Mn2O3 not recorded 0.08

SrO not recorded 0.1

Cl not recorded 0.011

A REVISED

CONSTRUCTION SEQUENCE

A construction sequence can now be proposed that incorporates all

the features of the tumuli now known.

It is based upon Luc

Chevalier's 1963 proposal for how the cement core was built on the

Isle of Pines, but substantially expands and updates it.

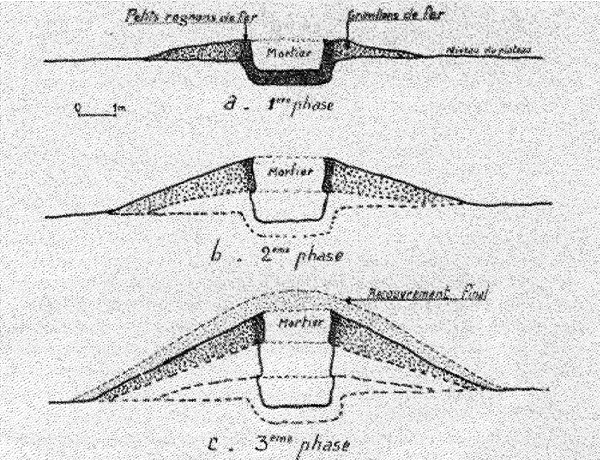

Figure 10:

Construction sequence of the cement core

on the

Isle of Pines as proposed by Chevalier, 1963 [his note 6].

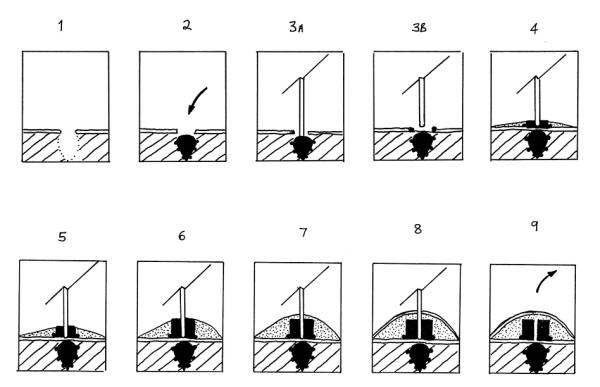

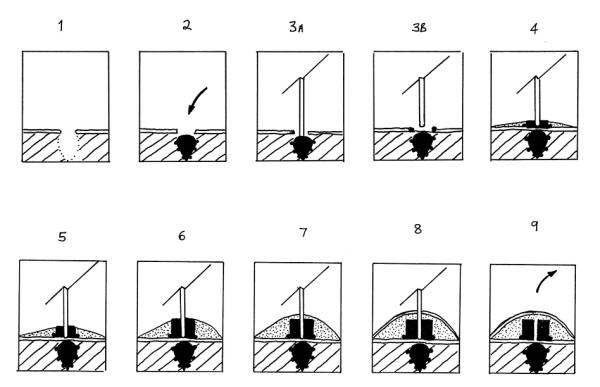

Figure 11:

Author's proposed construction sequence

in cross-section, incorporating all known features.

Stage 1

The necessary first step required excavation of a hole through

the topsoil and more than 2 meters deep into the ferruginous

clay layer beneath.

Stage 2

This was followed by placement in the hole of the almost 8

foot/2.4 meters long Fe cone-shaped object, its point downwards

and with at least 3 rings of Fe nuggets placed around it,

perhaps to stabilize it in a vertical position.

Their presence,

incidentally, makes it clear that the cone-shaped object is not

an artifact from iron being leached from the surface and somehow

precipitating into a geometrical shape below the tumulus.

Stage 3A

Vertical placement of a tubular pillar or "pylon" (a smooth tree

trunk?) of unknown length centered above the cone. Current

excavation data lacks the resolution to determine which of these

two possibilities is correct: (A) the pylon may have been placed

in direct contact with the rounded top of the cone, or:

Stage 3B

the pylon may have been separated from the top of the cone by a

shallow bed of Fe nodules and soil, the scenario utilized in

this model.

Stage 4

Over a bed of medium-sized Fe nodules, the first cement layer

was poured into the hole, thus stabilizing the pylon in

position.

At ground level the

base of the cement block was surrounded (delineated?) by large

Fe nodules, while a circular base layer of Fe gravel was added

around the cement core to the same height.

Local materials, consisting primarily of iron gravel but

inevitably also some soil, were scraped up in a circular fashion

around the structure, thus differentiating the scraped area from

the normal surroundings, creating the "aureole" effect still

visible in aerial images, as Chevalier noted.

Throughout its

erection, the outside surface of the cement core was reinforced

with various sized Fe nodules, in contrast to the softer cement

interior.

Stage 5

The second layer of cement was added, maintaining the same

dimensions as the first layer. Likewise, the Fe gravel was built

up around the core to the same level.

Stage 6

The third and final layer of cement was added, maintaining the

same dimensions and the Fe gravel built up around the core to

the same level.

Stage 7

A final, substantial, layer of Fe gravel was added to entirely

cover the cement core, completing the rounded shape of the

tumulus.

The small size and

particularly the weight of the gravel is such that it would have

rapidly filled the hole in the cement core, assuring us that the

pylon, or at least a "cap" of some type, was in place when the

gravel covering was added to the tumulus.

The simplest

explanation is that the pylon remained in place throughout.

Stage 8

It is unclear whether a final, thin, layer of soil was added to

cover the entire tumulus or whether the soil already mixed in

with the gravel sufficed. In either event, the tumulus was now

complete with only the pylon protruding from the hole in the

cement block.

Stage 9

At some point the pylon was removed (or if organic, such as a

tree trunk, perhaps rotted away) and the tumulus assumed its

innocuous modern appearance, giving no hint of the substantial

cement and iron structures within and below it.

At most tumuli in the present, the vertical hole in the cement

core is covered over by the vegetation growing in the tumulus

covering; for that reason, the hole was not readily visible to

early investigators.

Data are currently

insufficient to ascertain whether the shafts became clogged with

debris after removal of the pylon.

While apparently

intended to provide additional stability and strength, the very

substantial covering of iron gravel and soil also effectively

served to protect the tumuli from weathering and disguised their

nature until very recent times. 51

THE FUNCTION

OF THE TUMULI

Of the numerous reasons for building any structure elevated above

its surrounds (to provide a higher vantage point, to elevate

something for increased visibility, to use gravity to move something

(e.g. water) downwards, to funnel something (e.g. smoke) upwards and

so on), only a small number are potentially applicable to the

tumuli.

These are as follows:

1.

A burial site

As demonstrated

earlier, whatever else they may be, the structures are

manifestly not burial mounds. No skeletal material, or the

cultural artifacts associated with burials, have yet been

observed in the concrete-cored tumuli.

Human burials, of

course, are found in a variety of mounds or sub-surface sites

that do not resemble in any way the structures under discussion

here.

The human burial

mounds are smaller in height and extent, have no cement core at

their centre and are generally found in situations and locales

more commonly associated with funeral remains.

Purely as a note of interest, in 2019 the author and others

examined a large concrete-cored tumulus on private land at Gadji

which had been disturbed by road construction; a small number of

loose human bones were located just beneath the surface (a depth

of ca. 15 cm), an act of later, accretional, burial using the

surface of the mound as a convenience.

Here, in a classic

situation of an apparent exception proving the rule, the

obviously recent very shallow burial helps emphasize that these

structures were not originally intended to inter human remains,

a distinction readily apparent to most observers over the years.

52

Figure 12A, 12B (2 images):

The relatively recent burial just below the surface

of a large tumulus in Gadji.

The damaged concrete core in the centre of the tumulus

and the burial location on the right side

are both visible in image 12A.

Images by author, 2018.

2. As an

elevated vantage point or watchtower

This proposal lacks

any merit as abundant opportunities for higher views are

afforded by adjacent land features and trees. And, in any case,

it does not explain the cement core construction and the sheer

number of tumuli built.

3. As a

ceremonial or ritual centre

This concept finds

some support in a handful of locations where rock-lined paths

and other cultural indicators have been found.

Most recently, the

2006-2010 survey on the Isle of Pines identified pathways,

depressions and large ferralitic boulders atop 6 tumuli.

While ceramic sherds

remained "extremely rare" on the Iron Plateau, indications of

eaten seashells from the coast or "fossil uplifted limestone

blocks from the forest" were noted at 8 tumuli. 53

Investigation is

still required to determine if these works are contemporaneous

with the tumulus, or a later expansion by others. Logically, the

likelihood that the stones date to a much later period seems to

be strengthened by their rarity.

The oral tradition noted earlier that mentioned that "posts were

planted on the top of earth mounds and scenes of 'torture'" does

not offer support for ritual use any more than it does for a

funerary function; a post or tree trunk does not require a large

concrete base to ensure it stands upright.

If these traditions

have any substance they must refer to a usage postdating the

tumuli construction.

4. As an

artistic expression

The most obvious

objection to the structures being an art form that developed

uniquely in the area, is that their most impressive features -

the interior cement block surrounded by iron nodules - was

completely covered over with earth and clearly not intended to

be visible.

Nor would a circular

earthen mound require such an interior, one that remained

unseen. We would expect that an object of art would be adorned

with other features, either individualistic or symbols common to

the community.

Instead, with the

exception of the few locations noted in #3, we find only

conformity, an austere plainness that suggests a strictly

utilitarian, functional, purpose, not an artistic one.

A NEW PROPOSAL

By showing what the tumuli are not and cannot be, the purpose of

these structures can now be proposed with some certainty.

From an engineering

viewpoint the large cement blocks within the tumuli have the primary

purpose of stabilizing a circular pillar or pylon, standing in the

vertical shaft of the core but later removed or decomposed, for no

trace of them now remains.

Nor is there any hint of

what the pillar/pylon may have supported and why it required such a

degree of stabilization, as evidenced by the massive cement base.

Determining this is now the challenge going forward.

Ascertaining the function

of the cone-shaped metal object beneath the shaft may offer the most

promising line of future investigation.

Nothing to date suggests that the tumuli construction took place

over an extended period where we would expect to see improvisations

or the development of different styles. Everything suggests a

one-time concentrated effort.

Only two of the Paita tumuli preserve any trace - surplus raw

material - of the construction process and, just possibly, of a

stage of early experimentation with local materials.

If so, we can speculate

that the silica-based process may have been abandoned in favor of

the iron resources readily available on the Isle of Pines.

CONCLUDING

REMARKS

More answers will reveal themselves when modern archaeologists

engage more fully with the structures than they have heretofore.

It would require little

effort to completely reveal the interiors of those structures that

are already partly and even fully exposed; in particular, the large

cone-shaped iron structure which is the most likely feature to fully

reveal the final answers to the mystery.

Was this a type of

anchor, such as our modern anchor spears, for the pylon or pillar

sitting directly above?

While this artifact has

only been reported from one site, it beggars belief to think that

Chevalier chanced upon the one tumulus that had a symmetrical

cone-shaped metal object positioned exactly below the shaft in the

central core; it must be an integral part of other tumuli.

For that matter, we

cannot be sure that nothing else lies beneath the cone itself -

no-one has looked.

The incongruity of the scientific establishment, particularly

archaeologists and historians, in having Chevalier's excavation

reports since 1963 while still proposing solutions that do not, in

any way, account for what lies within these structures is

staggering.

The tumuli, after all,

remain readily available for examination. This inaction must

represent, in large part at least, the instinctive avoidance of

something that challenges present paradigms about human settlement

in the southern Pacific.

Surely the time is long past when data seemingly at odds with our

current thinking are ignored.

Perhaps in them lies a

key to a broader understanding of what influences and events have

shaped the Pacific's distant past even if, as the data in his paper

suggests, it requires a reconsideration of what we can possibly term

the "Neolithic" explanation.

It is hoped that this

paper will encourage archaeologists and historians of this region to

re-engage with facts and move beyond demonstrably inadequate

theories in solving the puzzle these structures still represent.

In the 21st century, the enigma remains. And if

Chevalier's questions were perceptive in 1963, decades later they

can be re-stated and expanded:

The identity of the tumuli builders remains, of course, the crux of

the mystery, but they certainly predated the arrival of the

Melanesians who became the generally regarded indigenous culture and

had no ability to manufacture concrete.

Who were they?

Where did their

ability to make high-quality concrete come from at a time when

this technology was unknown, certainly in the Pacific at least?

What possible motivation or purpose could cause a people to

invest so much effort to erect more than 400 of these

structures, each averaging a volume of 500 cubic meters? 54

Why did such a massive effort leave no other traces of its life

and activities - no tools, bones, charcoal, pottery or other

cultural artifacts, either within the tumulus or around it?

Why did they not use this ability to construct other works,

their dwellings, their burials and their sacred places before,

during, or after the tumuli construction?

Over time, why was the ability to manufacture such a useful

material as concrete not exported to other islands?

Why was this capacity

not passed down to the Melanesians who became the generally

regarded indigenous culture?

Indeed, why did this

capacity not arise elsewhere in the region?

The prescient questions

of Chevalier, pondering the mystery of a distant, unknown, people

who knew how to make durable concrete on a large scale, still await

resolution...

VIDEO

NOTES

1."The [Isle of

Pines] is considered to be a kind of "archaeological nightmare"

due to the presence of no less than 200 earth mounds…" Louis

Lagarde & Andre-John Ouetcho, "Rocks, pottery and bird bones:

new evidence on the material culture of Isle of Pines (New

Caledonia) during its 3000-year-long chronology," in Christophe

Sand et al. eds. The Lapita Cultural Complex in time and space:

expansion routes, chronologies and typologies (Noumea: IANCP,

2015), Archeologia Pasifika 4 series.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280976124_Rocks_pottery_and_bird_bones_new_evidence_on_the_material...

2. Jacques Avias, "Contribution a la Prehistoire de L'Oceanie:

les Tumuli des Plateaux de Fer en Nouvelle-Caledonie" in Journal

de la Societe des Oceanistes (1949), 15-50 (author transl.)

https://www.persee.fr/doc/jso_0300-953x_1949_num_5_5_1625

3. Louis Lagarde, "Geological anomalies?" in "Were those

mysterious mounds really for the birds?" Reappraising the Isle

of Pines' puzzling tumuli (New Caledonia)" in For a history of

Oceanian prehistory: historiographical approaches to

French-speaking archeology in the Pacific (Noumea: Pacific CREDO

publications, 2017).

4. Luc Chevalier, "Le problème des tumuli en Nouvelle-Calédonie,"Bulletin

périodique de la Société des Études mélanésiennes 14-17 (Noumea:

Société des Études mélanésiennes, 1963), 24-42.

www.archeologie.nc/docus/tumulcheval.pdf. The section titled

"Tumulus A Cylindre Double" reports the examination of an oval

double-cored tumulus and notes two others visible in aerial

images. Three related reports by Chevalier are also on file at

the New Caledonia Museum in Noumea: "Observations faites sur un

tumulus ouvert a LIIe des Pins" (3 pages) dated October 6, 1959;

"Note sur les tumuli de Nouvelle-Caledonie" (3 pages dated

October 21, 1960 regarding the mortar analysis) and a 5 page

handwritten draft dated January 15, 1961 of the article that

would appear in 1963.

5. Chevalier (1963), Figs. 4, 5.

6. Chevalier (1963). See Fig. 7 sketch in "Tumulus A Cylindre

Double."

7. Chevalier (1963), Fig.10.

8. Chevalier (1963), Fig. 5.

9. See Chevalier (1963) Figs.10 and 11 with notes.

10. Roger Curtis Green & J. S. Mitchell, "New Caledonian Culture

History: A Review of the Archaeological Sequence" in New Zealand

Journal of Archaeology vol. 5 (1983), 19-68.

11. Theophile Auguste Mialaret, L'île des Pins, son passé, son

présent, son avenir: colonisation & ressources agricoles (Paris,

J. André, 1897). Reprinted in 2012 (Paris: Hachette Livre BNF).

12. R. H. Compton,

"New Caledonia and the Isle of Pines," The Geographical Journal

vol. 49, no. 2 (London: Feb. 1917), 81-103, esp. 102-103.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1779337

13. Jacques Avias (1949), 15-50.

14. Jack Golson, "The Tumuli of New Caledonia" in "Report on New

Zealand, Western Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Fiji," Asian

Perspectives vol. 5, no. 2 (Winter, 1961), 170-172.

15. Jack Golson, "Rapport sur les fouilles effectuees a l'ile

des Pins (Nouvelle Caledonie) de Decembre 1959 li Fevrier 1960,"

in Bulletin périodique de la Société des Études mélanésiennes

N.S. 14-17 (1963), 11-24; Daniel Frimigacci & Jack Golson, "Tout

Ce Que Vous Pouvez Savoir Sur Les Tumulus, Meme Si Vous Osez Le

Demander" (1986), copy in author's possession.

16. Chevalier (1963).

17. Chevalier (1963), Fig. 5 in "Fouilles Sous Le Cylindre."

18. Chevalier (1963), see "Tumulus A Cylindre Double."

19. Chevalier (1963), see "Elevations Secondaires" and "Fouilles

Au Tumulus no 2."

20. G. Delabrias et al. "GIF Natural Radiocarbon Measurements

11," Radiocarbon, vol. 8 (Yale: The American Journal of

Science,1966), 88-89 (Gif-298, 299 and 300).

https://journals.uair.arizona.edu/index.php/radiocarbon/article/view/17972/17709

21. T. A. Rafter et al. "New Zealand radiocarbon reference

standards" Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on

Radiocarbon Dating. Vol. 2, (1972), 625-675, as referenced in

Lagarde "Were those mysterious mounds really for the birds?"

(2017). The same paragraph cites Dubois (1976) for the 12,900

ybp Placostylus dating although the dating was actually from

Chevalier, as reported in G. Delabrias et al. (1966) - see note

20.

22. H. C. Brookfield & Doreen Hart, Melanesia: A geographical

interpretation of an island world (London: Methuen, 1971), 78

references both Chevalier and Golson's work and summarized:

"…there seem to have been earlier - perhaps much earlier -

inhabitants of New Caledonia, who built tumuli of a concrete

made of coral lime…"

23. Fr. Marie-Joseph Dubois, "Trouvailles à l'île des Pins,

Nouvelle-Calédonie," Journal de la Société des Océanistes 51-52

(1976), 233-239. See especially the section Purè.

https://www.persee.fr/doc/jso_0300-953x_1976_num_32_51_2744

24. Richard Shutler Jr. "Radiocarbon dating and Oceanic

prehistory" in Archaeology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania

13, 2&3 (1978), 222 accepted that "…by 10,000 years ago, a non-Austronesian,

aceramic, pre-Neolithic, tumuli-building people were in Island

Melanesia, on New Caledonia and Ile de Pines…"

25. Peter Bellwood's opus Man‘s Conquest of the Pacific

(Auckland: Collins, 1978), 250 concluded: "The Isle of Pines

also provides one of the more unusual archaeological mysteries

of the Pacific….[dating gives] a very odd range of dates between

1000 and 6000 BC. which may be of questionable value." However

he notes: "Furthermore, it is not at all certain that the mounds

are man-made, but if they are, then perhaps a Lapita connection

may be found, or they may even have been built by some unknown

pre-Lapita inhabitants of New Caledonia."

26. Roger Green & J. S. Mitchell (1983) sensibly accept that the

concrete cores are an important indicator of a "cultural"

origin, dismissing attempts to label them as "natural" by

highlighting Chevalier's analysis of the concrete. They noted

that some snail shells attached to the cores and in the cement

matrix provided the oldest dating and believed some dating

inaccuracies might exist, but, despite preferring a later

dating, still accepted that the tumuli are manmade and likely

ancient: "…the enigmatic tumuli, or concrete-cored mounds,

provide a number of issues, the answers to which remain

uncertain. However, there are several lines of evidence to

suggest that these structures are man-made…at present these

tumuli present a problem which only further archaeology and more

data will resolve…it seems necessary to continue attributing at

least some of these tumuli with their cylinders and other

features to human activities, as they provide a range of

evidence not easily explained by any set of natural events…It is

only if some much earlier age estimates for tumuli are adopted

that they might be taken to imply initial occupation by a group

of non-Austronesian speakers."

27. Kerry Ross Howe in Where the Waves Fall (Honolulu:

University of Hawaii Press, 1984), 31 states: "New Caledonia

poses one of the more interesting problems in Oceanic

archaeology…the conical tumuli with an inner cylinder composed

of hard lime mortar. They are clearly of human making…Three

radiocarbon dates put their age at about 7000, 9500, and 13,000

years…These amazing dates may simply result from the testing of

material that was long dead before being used to build the

tumuli. On the other hand it is possible that the dates are

correct."

28. John R. H. Gibbons & Fergus G. A. U. Clunie, "Sea Level

Changes and Pacific Prehistory: New Insight into Early Human

Settlement of Oceania" in The Journal of Pacific History vol.

21, no. 2 (April, 1986), 58-82 accepted that at least some of

the 400 tumuli were "apparently man-made."

29. Christophe Sand, "Lapita and non-Lapita ware during New

Caledonia's first millennium of Austronesian settlement" in The

Pacific from 5000 to 2000 BP (Paris: Institut de recherche pour

le developpement, 1999), 139-159. Sand treated the dating as

established: "The discovery of large tumuli, dated between

13,000 and 4000 BP, was at the same time seen as indication of

an old settlement of southern Melanesia by modern humans…,"

later noting "The significance of this dating remains unclear…"

30. Patrick Vinton Kirch, On the Road of the Winds - An

Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands Before European

Contact (Berkeley: UC Press, 2000 and 2017), 135 accepted tumuli

dating as early as "10,950 BC" while still maintaining support

for the avian explanation.

31. Avias (1949), 48.

32. Frimigacci & Golson (1986), 1.

33. For example, see Lagarde, "Isle of Pines and the tumuli

research history" in "Were those mysterious mounds really for

the birds?" (2017), noting particularly publications of engineer

Bernard Brou, whose 1977 book, Préhistoire et société

traditionnelle de la Nouvelle-Calédonie (Noumea: Publications de

la Société d'Études Historiques de la Nouvelle-Calédonie) served

to popularize the migration theories of Avias, although Brou

himself had favoured a geological explanation.

34. In 2018, the author published a response to the 2017 release

of alleged US intelligence documents that included a claim that

traces remained on the Isle of Pines of an extraterrestrial

visit ca. 11,500 BP. Such an explanation will seem fantastic in

direct proportion to how current one's knowledge is of

astronomical advances; the author retains an open mind.

35. Francois Poplin & Cecile Mourer-Chauvire, "Le Mystere de

Tumulus de Nouvelle-Caledonie," in La Recherche 16 (Paris,

September, 1985), 1094. The same authors published "Sylviornis

neocaledoniae (Aves, Galliformes, Megapodiidae), oiseau Géant

éteint de l'ile des Pins (Nouvelle- Calédonie)," Geobios vol.

18, no. 1 (December 1985), 73-105.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016699585801820

36. Roger Green, "Those mysterious mounds are for the birds,"

Archaeology in New Zealand vol. 31, no. 3 (1989), 153-158.

37. John Connell, New Caledonia or Kanaky? The political history

of a French colony. Pacific Research Monograph 16 (Canberra:

Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU: 1987), 1-2.

38. Janelle Stevenson & John R. Dodson, "Palaeo-environmental

Evidence for Human Settlement of New Caledonia" in Archaeology

in Oceania vol. 30, no. 1 (1995), 36-41.

39. Janelle Stevenson, "Human Impact from the Paleo-environmental

Record on New Caledonia" in Jean-Christophe Galipaud & Ian

Lilley, eds. Le Pacifique de 5000 h 2000 avant le present / The

Pacific from 5000 to 2000 BP (Paris: Institut de Recherche pour

le Developpement, 1999), 251-258.

40. Patrick V. Kirch, "Resolving the Enigmas of New Caledonian

and Melanesian Prehistory: A Review," Asian Perspectives vol.

36, no. 2 (Fall 1997), 232-244]. An email exchange between the

author and Kirch in 2017 served to emphasize his support for the

avian hypothesis.

41. Patrick Vinton Kirch (2000 and 2017). The egg shell claim

appears on p.135 in the 2007 edition.

42. Sue O'Connor, "Pleistocene Migration and Colonization in the

Indo-Pacific Region" in Anderson et al. eds. The Global Origins

and Development of Seafaring (Cambridge: McDonald Institute for

Archaeological Research, 2010), 46.

43. Trevor H. Worthy et al. "Osteology Supports a Stem-Galliform

Affinity for the Giant Extinct Flightless Bird Sylviornis

neocaledoniae (Sylviornithidae, Galloanseres)," PLOS ONE 11(3):

e0150871 (2016).

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0150871

44. Golson (1963).

45. Frederique Valentin & Christophe Sand, "THE TÜÜ BURIAL

MOUND, ISLE OF PINES" in "Prehistoric Burials from New Caledonia

(Southern Melanesia): A Review," Journal of Austronesian Studies

2 (1) (Taiwan: National Museum of Prehistory, June 2008), 5.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260707175_Prehistoric_burials_from_New_Caledonia

46. Louis Lagarde, "Were those mysterious mounds really for the

birds?" (2017).

47. Frimigacci & Golson (1986), 31.

48. Louis Lagarde did not respond to multiple queries in early

2020 seeking clarification of his claim that the plateau tumuli

contain "no evidence of archaeological material."

49. Discussed in Golson (1961), 171. Additional instances where

these features were found appear in unpublished excavation notes

of Jack Golson in possession of the author.

50. Cement Australia, Darra Laboratory, Queensland, NATA No.

188, dated July 19, 2018.

51. A basic comparison of equal quantities by the author yielded

these results: 125 g of iron gravel was heavier than dry soil at

91 g, and even soil fully saturated with water at 113 g.

52. A review of earlier literature discussing the tumuli will

reveal how often the clear distinction between burial mounds and

the tumuli was apparent to skilled observers. One of the

earliest such accounts, for example, is Alphonse Riesenfeld's

wide-ranging Megalithic Culture of Melanesia (Leiden: Brill,

1950), 539 - 572, an interesting commentary on the times and

while dated, still of value.

53. See Lagarde (2017) "Anthropic aspects of the plateau tumuli"

in "Were those mysterious mounds really for the birds?" in

Lagarde (Doctoral Thesis, 2012), Peuplement, dynamiques internes

et relations externes dans un ensemble géographique cohérent de

Mélanésie insulaire: L'exemple de l'Ile des Pins en Nouvelle-Calédonie

(Paris: Université Paris I - Panthéon-Sorbonne), Tome 1, espec.

244-245).

54. Lagarde provides an estimate of tumuli volumes as averaging

about 500 cubic meters; see Lagarde, "Geological anomalies?" in

"Were those mysterious mounds really for the birds?" (2017).

|