Before us lay a pleasure trip during which we should travel many thousands of miles. We proceeded slowly when we came above the base of the huge bulk of Pitach Rhok, the mighty mountain, and ascended somewhat, so that we should be on a level with its high point. When at the place, nothing would suit the company except a stop on the summit, and together we all placed foot in the snows on the pitach, which thing was done chiefly to please Anzimee, who said that the place was very interesting on account of what had there happened to me.

Then, again, we were under way, descending from the higher altitudes in order to better view the thickly inhabited, though mountainous, country beneath us, between Pitach Rhok and east Poseid.

At the approach of sunset a dull roar arose to the ear, and soon the long white shore of old ocean flashed beneath a moment, and in a little time was fax behind, with the waters, lead color in the twilight, beneath, behind, before and on both sides, no land in sight, and over one thousand miles east the country of Necropan. Without going at a full rate of speed, we could not expect to be above that land in less than two or three hours. But as it would be dark ere reaching it, we slackened speed to an hundred and fifty miles per hour, closed the deck and went into the salon, where incandescent lamps lit up the darkening night-glooms.

A trip by vailx could never prove so monotonous as a journey in even the fastest of ocean steamships so often is to-day. The variety of scenery, the wide views possible, for altitude was dependent wholly on pleasure, the external cold being unheeded by people who sat in a parlor warmed by means

from Navaz and furnished with air of the proper density by the same Night-Side forces--all this tended to prevent ennui. Then too, the rapid transit changed the aspect of things beneath so fast that the spectator looking back-wards gazed upon a dissolving view. As an aside, the currents derived from the Night-Side of Nature permitted the attainment of the same speed as that of the diurnal rotation of the earth, e. g.: supposing we were at an altitude of ten miles, and the time the instant of the sun's meridian; at that meridian moment we could remain indefinitely, bows on, while the earth revolved beneath, at approximately seventeen miles every minute. Or, the reverse direction keys could be set, and our vailx would speed away from where it was meridian on the surface beneath, at the same almost frightful rate, frightful to one unused to it, as my reader is now, but one day will not be, if, as I hope, he or she will live to see vailxi rediscovered. Nor need the life be a very long one ere then.

While we had such preventives of ennui, we lacked not commoner means of enjoyment. We had our naima, in the mirrors and vibrators of which our friends, however distant, could appear in image of form and of voice, lifesized and with undiminished vocal volume. The salons of the great passenger vailxa had libraries, musical instruments, and potted plants, amongst the flowers of which birds similar to the modern domestic canary darted about.

At about the tenth hour it was reported that Necropan was beneath, and at this surprising information, because at the speed I had ordered, we should have been at least six hours longer in coming to that country, I enquired of the vailxman his reason for increasing speed without orders. No good reason being given, I severely reprimanded the conductor, and ordered that a descent be made to terra firma, in order that we might travel by day over the Wasted Land, as our word Sattamund may be translated, which is the Sahara desert of to-day. This great wade some of our party had never seen,

and to allow them the privilege we settled down to spend the night on an elevated ridge, high enough to be above malarious influences, for we were near where modern Liberia lies.

"The proud bird--The Condor of the Andes,

That can sail thro' heaven's unfathomable depths,

Or brave the fury of the northern hurricane

And bathe his plumage in the Thunder's home,

Furls his broad wings at nightfall, and sinks down

To rest upon his mountain crag.

Though we called it Sattamund, or the Wasted Land, yet it was not such an and region then as it is now. Water, if not as abundant as it was in Poseid, was abundant enough to give a wealth of tropical trees of the hardier sorts, sufficient at least to hide the nakedness of the slopes and hills of that old seabed. There were even a few saline lakes there, broad and blue, and it was around these that the population was centered. But the same dread catastrophe that overtook fair Poseid laid its terrible hand upon Necropan, and its beauty of verdure went out from the land, because the geological changes withdrew all the water from the surface, and hid it so that only artesian augers could find it. The same mighty throe rent the rocks through and through in Southwest Incalia, and to-day there is in that arid region scenery most fantastic, weird past the power of my pen to describe, where flows the Rio Gila, the Colorado, and Colorado Chiquita. But I will reserve the description, and when it is given it shall be in other words than mine, so that thou and I, my friend, shall together have the pleasure of enjoying a fine word-painting.

In Poseid and Suern, and wherever civilization extended its scepter, it was the universal law, and mankind's pleasure to obey the heavenly mandate which the general accordance with the solar life spirit taught us required the planting, instead of careless rejection, of O seeds of goodly flower or fruit, for shade, for beauty, for utility, wherever it chanced that a favorable spot offered, either in the habitats of man or in the untrodden wilderness. Indeed, in such trips as our party was then taking, it was a matter of religious significance to take great quantities of seeds and to scatter them from the vailx-decks

at nightfall, both as an offering to Incal, as His sublime symbol set in the west, and also that the dews of night might insure germination, and this ceremony was also held to be an acknowledgment of the Goddess of Increase, Zania. Thus the wilds came to bloom as the rose; and to-day the world is heritor of that sowing of seed; the indigenous cereals, the wheat, for the origin of which many ingenious but insufficient theories have been put forth, and the varieties of palms that make the tropics famed for the grace of their cocoas and dates, and every genera of the Chamaerops. And these things are because man, woman and child found pleasure in that olden time in "planting seed by the wayside." Go thou and do likewise, that the waste places may become full of beauty and be a joy forever. All hail to Arbor Days, which fulfill the injunction of Christ; they will surely make a return, and some an hundred fold. A small pocket now and then will hold many a seed for planting, and though thou heedest not its sort, so that it be goodly, yet the Father hath said, "It shall bring forth after its kind."

The morning dawned clear and cloudless and was altogether so delightful that we essayed scarcely any forward progress, moving slowly in order that the deck might be uncovered and the company allowed to sit out in the fresh air and warm sunshine.

Down below, a couple of thousand feet at most, we saw, through good glasses, various forms of . human, animal, bird and plant life; and sounds came up to us in drowsy, musical monotone, as our vailx hovered above. Towards evening the winds began to blow, rendering it unpleasant to remain so near the ground. The repulse-keys were set, and presently we were so high in the air that all about our now closed ship were cirrus clouds, clouds of hail held aloft by the uprushing of the winds, severe enough to have been dangerous had our vessel been propelled by wings or fans or gas reservoirs. But as we derived from Nature's Night-Side or, in Poseid phrase,

from Navaz, our forces for propulsion as well m for repulsion, or levitation, therefore our long, white, aerial spindles feared no storm, however severe.

As the windows, being frosted over, obscured our view, and as the night promised furious weather, we had recourse to books, music and to conversation with one another, and, through the naim, with our friends at home in faraway Poseid. No authority had Murus (Boreas) over the currents from Navaz. The evening had not far advanced when it was suggested that the storm would most likely be heavier, and the wind wilder nearer the earth, and so the repulse-keys were set to a fixed degree, making nearer approach to the ground than was desirable impossible as an accidental occurrence. We might, if it were generally agreeable, take advantage of our privilege and enjoy the sensation of being in the midst of the storm, ourselves safe and under full speed,

"And brave the fury of the Northern hurricane."

The partial novelty might make us sleep better, when, the evening passed, we should have gone to our staterooms. I, therefore, approved the plan, and gave orders to the conductor to descend to a height of about twenty-five hundred feet. Down we dropped. Our lights were made low in order to produce a partial gloom, the better to enjoy the full fierceness of the tempest, and we sat near the windows where we could hear, if not see. To the eye, naught would have appeared outside save entire blackness; to the ear, the loud beating of the rain upon the metal shutters was plainly, delightfully apparent. Against the sharp points of prow and stem the wind howled and shrieked like an army of demons. At times when the vailx was struck, broadside by some counterblast, it would careen and tremble, but it kept on its way, determined as a thing of life. The experience was enjoyable, if not entirely novel, for it spoke to us of the power of man over matter, and taught us of the things of God, Incal to us, Master of all things and of ourselves, who by Him had this authority over the elements.

When the sensation had become monotonous the lights were increased to proper brightness; again we turned to books and games and music, as we once more sought the upper regions of the atmosphere, which were quieter compared with those of the half-mile plane.

Anzimee and a girl companion sat apart from the rest of the company in a retreat formed of flowering vines draped across one corner of the main salon. In a short time she came from her nook to where I sat, wrapped in meditative obliviousness. Touching my shoulder as she came close, she said:

"Zailm, thou dost sing; it would please me if thou wouldst take thy lute and come to where Thirtil and myself have chosen seats, and sing to us."

She bent over my shoulder, blushing slightly, looking so altogether lovely that I simply sat and gazed in silent appreciation of her beauty.

"Come, Zailm, wilt thou?"

I arose promptly enough when I saw a shade of disappointment cross her face, as she interpreted my silence to mean unwillingness, and I said:

"Lo, Anzimee, I am but too pleased to comply, but how could I move?"

Unsuspiciously, she asked:

"Move? and why not?"

"Hast thou ever seen a bright bumming bird," I replied, "which, poised at a flower beside thee, kept thee still, almost afraid to breathe, lest it be alarmed to flight? Even so I could not move, lest--"

"There, there now! If I were not used to reading one's earnestness or other emotions in the eyes, I would say thou art a sad flatterer. But, come."

"What shall I sing, little friend?" I asked of Thirtil, a demure, sweet little maiden, an art student, half-serious, half-frivolous in temperament.

"Oh, dost ask me? Well, something, something," with a mischievous glance at Anzimee, "from thy heart!" she laughingly replied.

Anzimee blushed, but made no other sign, merely dropping her long lashes as I looked at her, while I said, "Truly! Then from my heart-this" (a popular favorite, by the way):

"Ere the heart can know its own,

Ere the doubts of life are o'er,

Love in our hearts must have grown

To the heights of heaven's shore.

Truly, love is sought in vain

In other place than in the heart;

True love always hath its pain,

When from purity we part.

May we cease from every strife,

While in lovely verse enshrining

Incal's blessing in our life;

With His peace it e'er entwining.

So is melody divine,

When the music of the soul;

'Tis betrothing thine and mine,

While the centuries unroll.

Yet our hearts are young and gay,

Seeking ever fairest bowers

Where shall bloom from day to day,

All the beauty of the flowers.

There is one of all the rest,

That alone for me is blooming;

Deep the tendrils in my breast,

Find forever their entombing.

Shall I pluck it while in bloom,

Ready for the gardener's gleaning?

Could I take forever home

What, unto me, is no dreaming?

Yea, beloved, we shall rejoice

In His blessing evermore;

List'ning to the gentle voice,

That as One--we do adore."

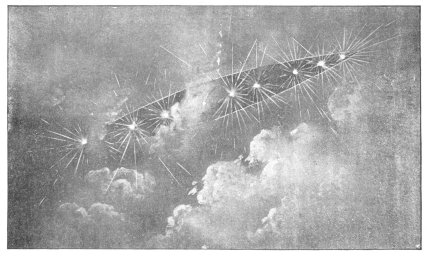

Thus it was within the vailx, song and pleasure; without was the storm, risen up after us. Into the teeth of the furious gale plunged our long spindle, giving no sign exteriorly, even had any one been there to see, of the light and warmth, laughter and song, of the human freight and songbirds within its staunch shell, amidst the flowers, a drifting bit of the tropics, safe from boreal blasts. No sign, save only the gleam of the crimson fore and aft lights.

While the others retired for the night to their various state

rooms, I remained in the vacated salon until the announcement was made to me that we were above Suernis. No landing could be made, however, in the face of a gale blowing eighty miles an hour, such an attempt would have resulted in being dashed to pieces the instant we reached the ground.

In order that we might be wholly out of the range of the influence of the storm, I gave directions to rise above the level of the disturbance, if such a region of calm existed within reach, and there set the keys so as to stop all propulsion. Receiving this order, the conductor augmented the repulsion force by means of the levers of degree, and we rose steadily up, up, up--above the clouds, above the rush of the hurricane, into a clear, calm atmosphere, intensely cold, almost thirteen miles from the earth's surface. Could we have had a view unobstructed by stormclouds, we were just about high enough to afford us a horizon of three hundred and fifty miles. Soon after this order I went to my room to bed. With the morning the storm had not decreased in fury; and occasional flurries in the air above us proved that the storm-area on the surface must be of vast extent. The cold outside was too intense to consider, even for an instant, the opening of the deck; the sky was almost black in the depth of its blueness; the sun, shorn of much of its dazzling brightness, appeared strangely dim, and the stars were visible. The steady motion of the air-dispensers as their wheels and pistons worked to maintain the interior air at a normal pressure was painfully apparent in the awful stillness, while the fizz of the air escaping through the fine crevices around the windows and edges of the deck made such a noise that I ordered the setscrews tightened and the ventilator pipes opened. Had the frost not hindered vision through the windows and, with the clouds, prevented a view of the earth's surface, a sight most peculiar would have been presented. The view toward the extended horizon would have made the apparent union of earth and sky seem almost on a level with us; but directly beneath, the fun separation from the solid globe would have seemed, not like a ball but like a huge bowl, ornamented with landscape scenes in its interior. As,

however, we could not see, our songs, our reading, and our conversation went on, whilst the very faint beams of Incal, coming through the frosted glass, were supplemented by the some knowledge which gave us heat and air and position, to defy the cold and the rarefaction and gravitation--knowledge of Navaz.

At home in Poseid there was no storm, but Menax, at the naim, told us that the weather office anticipated one, the one of which we at that moment awaited the abatement. We waited until the sun set in the west and came in sight in the east twice.

Several times the Saldu appeared at the end of the salon, seeming in the mirror of the naim as real and present as if, in verity, a third of the globe did not separate us. Once, only, she spoke, and then in a whisper to me, as, I stood near the naim:

"When, my lord, wilt thou be at home? A month? 'Tis long, 'tis long!"

A report of even the smallest events of our trip was furnished the news office, and was printed upon the discs of the public vocaligraphs, to use a word of modem sound, and long before any landing was effected by us on the soil of Suernis our fellow countrymen were acquainted with the story of our enforced suspension between heaven and earth while biding the abatement of the storm. Speaking of the vocaligraph leads me to remark that the social superstructure of Poseid was maintained upon the broad basis of equitable laws laid down by the great Rai of the Maxin-time through the influence of free speech as made and molded by church and school, and expressed through the millions of vocaligraphs the three rendering secure the integral homes which, aggregated, formed the nation.

At last the storm king withdrew his forces and the time had come for our descent. Down we swept from the vault of heaven, into Ganje, capital city of Suern.

Hast thou ever been in the ancient and long-deserted city of Petra of Seir? That very peculiar city at the foot of Mount Hor, a city hollowed from the living rock? Quite likely not, for the followers of Mahomet make it hard to visit the place. But if thou hast read thereof, then thou hast some idea of Ganje, in old Suerna, built in the cliffs of the river banks.

Such details as embrace the manner of our reception are too trivial to fill this record. Suffice it that it was suited to the friendly international relations of Suern and Poseid, and to my station and rank as a high deputy. Rai Ernon was far less interested in the vase and in the other gifts of gold and gems, than in the captive Saldani whom the tokens commemorated, particularly in the Saldu, Lolix the Rainu. I was startled at the monarch's close knowledge of the whole affair in all its details, and of my sickness and other incidents which were not matters of public note; but I betrayed no such feeling, since it was but momentary and passed as soon as recollection of Ernon's wonderful occult powers came to me.

Speaking of the Saldui, but especially of Lolix, he said:

"I did not send the Chaldeans unto Gwauxln as objects of lust, neither as a retributive punishment, that by exile from their native Chaldea they might atone to Suern for their fathers, sons, brothers, or husbands who worked harm to Suernis. No, doubtless they were not more blameable than is a tiger which hath a similarly destructive nature, but by the laws of Yeovah we find that ignorance of the law never exempts a wrongdoer from penalty. Law says in regard to sin: 'Thou shalt not.' And the penalty lies alongside, inexorably, and is dealt out unsparingly for disobedience. Law, therefore, appears not to be retributive, but educational. Having felt the punishment, no one, either man or animal, is apt to try the error twice out of curiosity. Nature makes no penalty easy, saying: 'When thou hast learned, then the punishment shall be more severe.' If a babe fell over a cliff, its death would be the result, though its innocence knew nothing of sin, just as surely as a knowing man might meet the same fate deliberately. Now the Chaldean women needed to learn that

conquest, bloodshed and pillage is a sin. The Chaldean nation needed a lesson also. It received it, in the death of its prize soldiery. But such examples need finish; a diamond in the rough is surely a diamond, but how much doth the lapidary increase its beauty and value! Not to release unto them those women was to that nation what the faceting is to a gem. Thinkest thou not that I am right?"

"Even so, Rai," I responded.

For several days we remained in the capital, and during this time were escorted over it by no less a person than Rai Ernon himself.

It was a strange people, the Suerni. The elder people seemed never to smile, not because they were engaged in occult study, but because they were filled with wrath.

On every countenance seemed to rest a perpetual expression of anger. Why, I pondered, should this thing be? Is it a result of the magical abilities they possess? By what seems to us of Poseid mere fiat of will these people appear to transcend human powers and set at naught the immutable laws of nature, though it can not be said that Incal has not limited them as surely as He has limited our chemists and physicists. The Suerni never lift their hands in manual labor, they sit at the breakfast or the supper table without having previously put upon it anything to eat, or elsewhere prepared a repast; they bow their heads in apparent prayer, and then, lifting up their eyes, begin to eat of what has mysteriously come before them--of wholesome viands, of nuts, of all manner of fruits, and of tender, succulent vegetables! But meat they eat not, nor much that is not the finished product of its source, containing in itself the germ for future life. Hath Incal exempted them from His fiat as Creator of the world, which all men suffer, "In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread?" It is less onerous, certainly, on those who walk His paths, or even those who partly do so, and whose rule of life is continence. Such are more powerful, have occult powers that no eater of meats can ever hope to attain, but surely they are not wholly exempt; it must be somewhat toilsome to perform

such magic feats as these. None ever got something for nothing. These people gaze upon the foes who come to menace them in their homes--and they are not!

"It passed o'er

The battle plain, where sword and spear and shield

Flashed in the light of midday--and the strength

Of serried hosts is shivered, and the grass,

Green from the soil of carnage, waves above

The crushed and moldering skeleton."

What Poseida could do these things? Rai Gwauxln, Incaliz Mainin, but no more, at least none known to the public even by repute. But no man of all Atl had ever witnessed much display of such power on the part of either, and with the masses it was mere repute. I was favored beyond most Atlanteans in this respect.

I noticed in our visits in and about the capital a thing which cast a shadow over me,, that his people did not love Ernon, however much they respected him and feared his power. That the Rai was aware of my knowledge of this dislike was obvious from his conversation.

"Ours is a peculiar people, prince," he said to me. "During many years, centuries even, it hath had to reign over it rulers come from the Sons of the Solitude. Each and every one hath striven to train his subjects so as to fit some future generation for initiation, as an entire people, into the mysteries of the Night-Side of Nature, deeper than thy people of Poseid have ever dreamed of going. To this end moral codes have been insisted upon as a coefficient of tuition in operative magic. But the endeavor hath never produced the end sought; only here and there hath an individual arisen and progressed; soon every one of these hath fled away from the less energetic people and gone to the solitudes, to become one of the 'Sons' of whom thou mayst have heard; generically we term these students' 'sons; specifically we would have to refer to them as 'sons' or 'daughters,' for sex is no bar to occult study."

It had long been a matter of interest to me to learn all I could of this band of Nature students, Incalenes, as they

were sometimes called, from Incal, God, and "ene," to study. Thousands of years later, in the time of Jesus of Nazareth, these were called "Essenes." But Atla, which possessed such a wealth of literature, had, with a single exception, no books on the subject. In that exception, a little volume printed in ancient Poseidonic, the details were very meager; yet its perusal had been of great interest to me. As I now listened to Rai Ernon, my interest was reawakened, and I thought I might one day become a candidate for admission to the order, if--but that "if" was of a large size. If the study renders the student so wrathful in soul as I see the Suerni are, then I will have nothing to do with it. The seed was planted, however, and grew a little when I learned that the angry gloom was not due to occult study, except in the sense that the lower nature was rebellious against the purity of the study and cast up the mud of anger, rendering turbid the clear waters of the soul. It grew still more when the Rai remarked later on that "the girl Anzimee would one day be an Incalenu." But the growth was not great in that olden time; it was reserved for a life to come, when: decades upon decades of centuries had flown, till now!

The Rai continued: "Ye of Poseid dip a little into the Night-Side, and behold! out of it ye gather forces which open the penetralia of the sea, and of the air, and subject the earth. 'Tis well. But ye require physical apparatus; without it ye are nothing powerful. Those, versed in occult wisdom need no apparatus. That is the difference between Poseid and Suernis. The human mind is a link between the soul and the physical. Every higher force controls all those lower. The mind operates through odic force, which is higher than any speed of physical nature; hence controls all nature, nor needeth apparatus.

"Now I, and my brother 'Sons' before me, have striven to teach the Suerni the laws which govern the operation of this force. Through this knowledge Yeovah leadeth His children,

strength. Hand in hand with this knowledge are physical acts, powers that come early in the study. So far have they gone, hut will no farther go.

"Morality aids serenity of soul; hence it is profitable to the Incalene, above all things, to be moral. But man is an animal in his corporeal self, and the passions thereof are pleasant. Love is of twofold nature: love of God and of the Spirit, pure and undefiled, and love of sex, which may likewise be pure, though if the dominion of the animal in man be over it, and so not so that of the human, it shall cause the man to sin, for then it is lust. I have sought that the Suerni may know the law,, that they maybe the masters, not the creatures, of circumstance. But because they know a few things of magic, and in the greater feats were aided by the 'Sons' dwelling amongst them, lo, they are content. And behold! they rebel against punishment on account of the lustful nature they do indulge, and curse me mightily because I exact obedience to the law, and penalty for the infraction thereof; and they curse my brother 'Sons' who do aid me, therefore is their wrath which it hath so troubled thee to witness. My people do things strange in thy sight, O Poseida, yet have no -wisdom why it is so, and work their wonders heedless of Yeovah. Wherefore they are a brood of sorcerers, and do not work white magic, which is beneficent, but black magic, which is sorcery. It shall work them exceeding woe. I would, O Zailm of Poseid, have taught these my people faith, hope, knowledge and charity, which same make pure religion undefiled. Have I not done well? Gwauxln, my brother, have I not done well?"

Rai Ernon was sitting in the salon of the vailx, and now addressed Gwauxln of Poseid, whom I saw in the naim as I looked around.

"Verily thou hast even so, my brother," said Gwauxln.

For some moments the noble ruler was silent, and I could see teardrops falling occasionally from beneath his closed eyelids. Then he opened his eyes and began a most touching apostrophe to, and in some sort against, his people.

"Oh, Suernis, Suernis! I have given up my life for thee!

I have striven to lead thee into Espeid (Eden) to teach thee of its beauties, and thou wouldst not! I have tried to make thee van of all nations and thy name synonym with justice and mercy and love of God, and how hast thou requited me? I would be as a father to thee, and thou didst curse me in thy heart! Keener than knives is ingratitude! I would have led thee to the heights of glory, but thou wouldst rather lie in wallow of ignorance, like swine, content to do what are marvels to other people, but thyself all ignorant of their import. Thou art an infidel, ingrate race, believing not in Yeovah, content to live by the little thou knowest, too slothful to learn, more ungrateful to Yeovah than to thy Rai! O, Suernis, Suernis, thou hast cast me off and made my heart to bleed! I go. From thy midst the 'Sons' go also, a mournful band of disappointed men. And thou shalt become few where thou art many, a derision before men and a prey to the Chaldeans; yea, thou shalt dwindle and shalt wait until the centuries--even ninety centuries, are fled into eternity. And in that day thou shalt suffer until the time of him who shall be called Moses. And of them it shall be said, 'They are the seed of Abraham.' And behold, even as now the Spirit of God is abroad in the land, immanent in the Sons of the Solitude, and ye do mock It, so in a remote day shall His spirit become manifest and shall incarnate as the Christ, and so shall the perfect human glow with the Spirit, and become First of the Sons of God. Yet shalt thou even then know Him not, but shalt crucify Him; and thy punishment shall go down the ages until that Spirit comes again in the hearts of those who do follow Him, and finds thee scattered to the four winds! Thus shalt thou be punished! From now until then shalt thou earn thy bread by the sweat of thy face. Thou shalt no more have the regal power of defense, lest thou use it for offense. I will no more restrain thee. My people, oh, my people! Ungrateful! I forgive thee, for thou canst not know how I love thee! I go. Oh! Suernis, Suernis, Suernis!"

At the last word the noble ruler's voice lowered to a murmur, and he buried his tearful face in his hands and sat

bowed in silent grief, except for a sigh of sorrow which once or twice he uttered. Several Suerni had heard his words, and these now left the vailx very quietly and went to the city.

"Rai ni Incal."

I turned to the naim as these words were uttered, and noted that a great shade of sadness rested upon the face of our own Rai, Gwauxln, as he looked upon Ernon--like himself, an Adept Son.

"Rai ni Incal, mo navazzamindi su," which being translated, is, "To Incal the Rai; to the country of departed spirits he is gone!"

Startled I looked around at the Suern Rai, who still sat silent as before, in the same position. I spoke to him, yet he gave no sign. Then I bent and gazed through his fingers into his fine gray eyes. They were set, indeed, and the breath of life was fled. Yea, verily, he had gone, even when he said "I go."

"Come unto me, Zailm," commanded Gwauxln.

I went to the naim and stood waiting.

"Are thy friends all within the vailx?"

"Even so, Zo Rai."

"Take then thy guards and seek the palace of Rai Ernon. Call upon his ministers to come before thee and tell them that their Rai is deceased. Tell them that thou wilt take his body in charge and carry it unto Poseid. Amongst the ministers are two elderly men and sedate; these are Sons. They are of that body of disappointed men who go forth from Suernis according to the words of Ernon. These two will know that thou speakest truth when thou sayest that Ernon of Suern hath left his Raina in my hands to govern as I shall decide is most wise. But the others will not know and the Sons will leave to thee the telling of the facts. Great shall be the anger of them that are not Sons, so that they shall try to destroy thee by their terrible power, disliking to be told that they are deposed from authority. Nevertheless, this do and fear not; be of good cheer, for how shall a serpent bite if it hath lost its fangs?"

When, according to these orders, I had the court before me, I spoke as directed by the Rai. It was received with a courteous smile by the two who by their demeanor I recognized as the Sons of the Solitude. But by the others great anger was shown.

"What! and thou, Poseida, offerest us such indignity? Our Rai is dead? We are pleased! But we, not thou, will attend to the funeral rites. As to the government of Suern, we laugh with scorn! Begone! We are our own masters. Leave us our ruler, and thou, dog, leave this country!"

For reply I repeated with emphasis the assertion of my authority. I confess to having felt an inward fear when the brow of one of these never-smiling men clouded with intense anger, as he pointed his finger at me, and said:

"Then die!"

I did not outwardly shrink, though half expecting to perish on the spot. Neither did I feel any death tremor, though the menace, ever before fatal, was not withdrawn. Gradually the minister's fury gave place to surprise, and he dropped his arm, gazing at me in amazement. I ordered my guards to manacle and take him to the vailx. Then I said:

"Suern, thy power is fled. Thus said Ernon. He hath said that henceforth thou shalt earn thy bread by the sweat of thy face. Over this country Poseid shall rule. I, special envoy of Gwauxln VII, Rai of Poseid, do depose all ye that are here from rulership, except those two who offered not scorn but courtesy. While they remain, which will not be long, I will make them governors over Suern. I have spoken."

Indeed, I had spoken, and that, to so great an extent, unauthorizedly. I was in an agony of doubt lest Rai Gwauxln should rebuke me. But I would not reveal my real weakness to these ingrates. Instead, I took a roll of parchment and wrote from memory the form of commission of governors of provinces in Atla, appointing one of the Incaleni to the office. This I sealed with my name as envoy extraordinary, following that of Gwauxln as Rai, using red ink, for which I sent a messenger to Anzimee at the vailx. My reason for appointing

one of the Sons as Governor was that only one would serve. The other chose to ask passage to Caiphul in my vailx. Then, giving the Governor his commission, a document which he received with the remark, "Thou art a man, indeed, not longer a boy;"--words which, though so kindly meant, fell on heedless ears at the time, for as I made my return to the vailx I felt actually heartsick at what I feared had been the acme of indiscretion on my part. I called for Rai Gwauxln, and when he responded I told him what I had done. He looked grave, and said merely the words:

"Come home."

Imagine now my distress. Not reprimanded, nor commended, but without any explanatory clue whatever, I was ordered home. Then it was that I sought Anzimee, and having found her in her stateroom I told her all the story. Our Rai was known to be one who could be severe in his punishments, although these took the form of disgrace meted out, as public dismissal from office for being unworthy of trust. Anzimee was very pale, but said hopeful words:

"Zailm, I see not but that thou didst right well. And yet, why was our uncle so gravely reticent? Let me give thee a potion; lie here on this couch, and take what I give thee."

She poured a few drops of some bitter drug, put in a little water, and handed the cup to me to drink from. Ten minutes later I was asleep.

Then she left the room and, as I afterwards learned, called her royal uncle to the instrument, where she laid the case before him. He was troubled at the effect of his words upon me, an effect. not intended, as he told her, and one which would never have occurred if he had not at that time been engaged in solving the very abstruse political problem presented by the new aspect of affairs through the decease of Rai Ernon. What further he said was: "Be not worried because Zailm is called home for no purpose of punishment, since I am well satisfied and called him for quite another reason."

I slept for hours, and when I at last awakened, Anzimee, sitting beside me, told me all that Gwauxln had said. As it

was then nearly night, I concluded to go to my own room and prepare for the evening repast. On the way I met the Son who was going to Caiphul with us. To this person it seemed a great novelty to travel as he was then doing, although his remarks on the subject were few.

It was, as I reflected upon it, something of a novelty to be piercing the air at the rate of seventeen miles each minute, a mile above the earth. I tried to fancy how it would seem to one like my passenger to be doing this thing; but after five years of familiarity with it as a means of travel, I had poor success in attaining a sense of his feelings concerning the experience.

As we traveled westward the sun seemed to remain as it was when we left Ganje, for its speed, or that of the earth, rather, was the same as our own. We had been on the way for five hours and had covered considerably over half of the distance home, the whole journey being something like seven thousand miles. The remaining two thousand miles would occupy some three hours for transit, a length of time which seemed to my impatient desire so long, that I paced the floor of the salon in very fretfulness. I have seen, since the days of Poseid, a time when a vastly slower progress would have seemed swift, but then the past had a veil obscuring it so that comparison was impossible--

"Man never is, but always to be blest."