|

by Elysium Health

December 18,

2017

from

EndPoints Website

Animations by Zolloc

for

Endpoints.

Two leading

scientists

explain how

circadian rhythms work

and offer advice

on lifestyle changes

to improve your

health...

Editor's Note:

This story is

focused on the

science of

circadian rhythms,

the 24-hour

physiological patterns

that most

organisms,

including

humans, follow each day.

This article is

intended to review the current

science on the

topic and not principally to offer advice,

though we do

present potential lifestyle modifications.

It is not an

exhaustive review of the field of research,

and we will

continue to update it

as more science

emerges.

Highlights:

-

Maintaining consistent and healthy circadian rhythms

may help improve overall health and prevent chronic

diseases.

-

Think beyond sleep: Circadian rhythms are influenced

by eating, exercise, and other factors.

-

Learn the idiosyncrasies of your own rhythms, your "chronotype,"

then adapt them to the best practices indicated by

scientific research.

Before You Start -

A Quick Glossary

-

Circadian:

Recurring

naturally on an approximately 24-hour cycle, even in the

absence of light fluctuations; from Latin circa

("about") and diem ("day").

-

Zeitgeber:

An environmental

cue, such as a change in light or temperature; from German

zeit ("time") and geber ("giver").

-

Endogenous:

Having an

internal cause or origin.

-

Entrainment:

Occurs when

rhythmic physiological or behavioral events match their

period to that of an environmental oscillation; the

interaction between circadian rhythms and the environment.

-

Diurnal:

Daily, or of each

day; from Latin dies ("day") and diurnus

("daily").

-

Master Clock:

A pair of cell

populations found in the hypothalamus, known as the

suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN); these cells contain the

genes that govern circadian rhythms.

-

Mutant Gene:

A permanent

alteration in a DNA sequence that makes up a gene; used by

chronobiologists to identify clock genes, by identifying the

mutant gene on animals with arrhythmic circadian habits.

Picture a plant trying to perform photosynthesis at night...

Without light, it's a

short drama...

"Plants are dealing

with life and death," said Sally Yoo, assistant professor in the

Biochemistry and Cell Biology Graduate Program at the University

of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), somberly.

"If they don't follow

circadian rhythms, they'll die."

For humans, the prognosis

would be slightly less bleak.

"Even if you deleted

the clock gene [an important gene regulating circadian rhythms],

you wouldn't die immediately," Yoo said. "But you will suffer."

Likely problems?

Constant psychological

confusion and heightened risk for chronic disease, among other

things. Life's tough when everything's out of sync.

Sally Yoo's

colleague, Jake Chen, an associate professor in the same

department, put it another way:

"In our life, we say,

'Timing is

everything.'

But that's an

exaggeration.

It is not, however,

an exaggeration to say,

'There is an

optimal time for everything.'

In our body, it's the

same.

Within individual

cells and within each tissue or organ there's a time for every

physiological process. The circadian clock is the master

mechanism, or timer, to make sure that everything runs smoothly

and according to plan.

That is a fundamental

function."

About

the Experts

-

Scientist: Zheng "Jake"

Chen

Education: Ph.D.,

Columbia University, NY, Postdoctoral Fellow, The University

of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX

Role: Associate

Professor, Biochemistry and Cell Biology Graduate Program,

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Recent Paper:

The small molecule Nobiletin targets

the molecular oscillator to enhance circadian rhythms and

protect against metabolic syndrome.

Area of Study: Small

molecule probes for chronobiology and medicine.

-

Scientist: Seung-Hee

"Sally" Yoo

Education: Ph.D., Korea

Advanced Institute of Science and Technology

Role: Assistant

Professor, Biochemistry and Cell Biology Graduate Program,

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

Recent Paper:

Period2 3'-UTR and microRNA-24

regulate circadian rhythms by repressing PERIOD2 protein

accumulation.

Also,

Development and Therapeutic Potential

of Small-Molecule Modulators of Circadian Systems.

Area of Study:

Fundamental cellular mechanisms in circadian rhythms and

deciphering physiological and pathological roles of the

clock.

Chen and Yoo study

circadian rhythms, the 24-hour physiological patterns that most

organisms, including humans, follow each day.

These rhythms are

hardwired from millions of years of the world spinning around. The

system is old, robust, flexible.

It's the product of an

organism's internal biological clocks and environmental cues - most

notably, the sun, but also many other factors - which govern our,

-

behavior

-

hormone levels

-

sleep

-

body temperature

-

metabolism

The so-called "master

clock" governing human circadian rhythms is the suprachiasmatic

nucleus (SCN),

a pair of cell populations packed with genes that carry out this

function (including Clock, Npas2, Bmal, Per1, Per2, Per3, Cry1, and

Cry2), located in the hypothalamus portion of the brain.

While molecular clock

genes also exist elsewhere - the kidney, liver, pancreas, muscles,

so on - the SCN acts as the chief executive officer, instructing

the rest of the body to stay on schedule and figuring out how to

incorporate cues from the environment.

(For a brief digression,

see how exactly the SCN works in an interactive feature by

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute.)

As we'll discuss later, being good to our natural rhythms improves

daily physiological and psychological function - and ultimately

short- and long-term health.

Reducing the wear and

tear on the clock keeps it fresh, maintaining what Yoo called "a

robust clock" later in life.

Chen was even more

emphatic:

"I cannot emphasize

enough how important the circadian rhythm is for prevention of

chronic diseases," he said. "And for long term benefits toward

health-span and eventually life-span."

The History -

Establishing the Fundamental Biology of Circadian Rhythms

The first thing to know about the study of circadian rhythms, also

known as chronobiology, is that with few exceptions all

organisms on the planet follow a circadian clock.

From daffodils to

sparrows, zebras to humans, everything under the sun follows the

pattern of the sun.

In 1729, French scientist

Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan recorded the first

observation of an endogenous, or built-in, circadian oscillation

in the leaves of the plant Mimosa pudica.

Even in total darkness,

the plant continued its daily rhythms...

This led to the

conclusion that the plant was not simply relying on external cues,

or zeitgebers, but also its own internal biological clock.

Portrait of French astronomer and geophysicist

Jean-Jacques Dortous de Mairan (1678-1771)

by

artist Simon Charles Miger.

Two hundred years later, in the mid-20th century, the

world of modern chronobiology blossomed.

The field benefitted from

contributions from a number of scientists, notably,

Colin Pittendrigh, the "father

of the biological clock." Pittendrigh studied the fruit fly

Drosophila and shed light on how circadian rhythms entrain, or

synchronize, to light-dark cycles.

Jürgen Aschoff, a friend of

Pittendrigh, also studied entrainment modeling, although they

reached different conclusions about the manner in which

entrainment occurs (parametric versus non-parametric, which you

can read more about

here and

here).

John Woodland Hastings and his

lab also made important foundational discoveries about the role

of light in circadian rhythms by studying luminescent

dinoflagellates, a type of plankton.

Erwin Bünning, who studied plant biology, also contributed

foundational research in entrainment modeling, describing the

relationship between organisms and light-dark cycles.

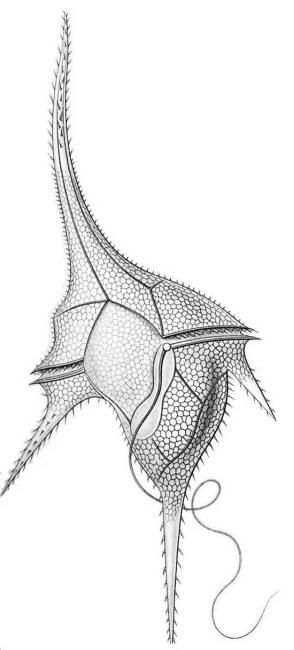

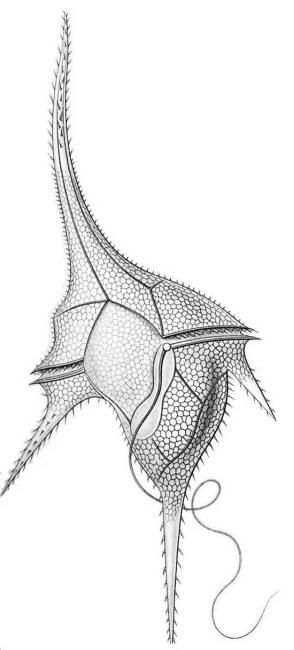

Ceratium hirundinella,

a

dinoflagellate.

Ernst

Haeckel (1834–1919)

The next phase of chronobiology discovery began to

articulate the specific molecular and genetic mechanisms of

circadian rhythms.

This came from the work

of

Ron Konopka and

Seymour Benzer, who in the

early 1970s aimed to identify specific genes that controlled the

circadian rhythms in fruit flies.

Konopka and Benzer are

credited with discovering that a mutated gene, which

they called 'period,'

disrupted the circadian clocks of the flies.

This was the first

discovered genetic determinant of behavioral rhythms.

-

Jeffrey C. Hall

-

Michael Rosbash

-

Michael W. Young,

...expanded Konopka and

Benzer's work by successfully showing

how the 'period' gene worked on the

molecular level.

Hall, Rosbash and Young

- who were awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or

Medicine - isolated the 'period' gene, and then showed how the

clock system worked on a molecular level.

Jumping from fruit flies to mice, Joseph Takahashi and his

team discovered the

mammalian clock gene in 1994 -

appropriately dubbed clock - and characterized it as an,

"evolutionarily

conserved feature of the circadian clock mechanism."

This gene discovery,

along with the body of work by Hall, Rosbash, Young and the

scientist Michael Greenberg, led to a watershed in

chronobiological knowledge.

Within a few years, the

genes informing circadian rhythms in lower organisms were largely

worked out.

Things have progressed steadily ever since, and, many of the

findings in fruit flies and mice have shown remarkable conservation

across species, meaning that there are analogous circadian genes

that control the rhythms of more complex animals,

including humans.

"The rising and the

setting of the sun is still the primary influence on circadian

rhythms, but other systems have steadily grown in scientific

inquiry."

The Current Research

- Articulating the Role of Circadian Rhythms in Human Health and

Disease

It's important to note that the biology of circadian rhythms is

incredibly complex - there are multiple scientific journals

dedicated to the field of research - and as a result our

understanding of the role biological clocks play in health is mostly

a result of animal studies and human epidemiological studies.

The experiments in lower

organisms help articulate the molecular and genetic mechanisms at

play, and then scientists can look at, say, how sleep disruption

leads to

increased incidence of,

-

type 2 diabetes

-

obesity

-

cardiovascular

disease

Indeed, one area of study

that's especially promising

is sleep.

Scientists are now

implicating a lack of sleep and the consequent disruption of

circadian rhythms in the development obesity and depression, as well

as most chronic diseases.

Studies even show that a

lack of sleep may have unexpected side-effects like

not being able to read facial

expressions.

The understanding of how circadian rhythms work has also expanded

well beyond interaction with the light-dark cycle.

"We have social cues,

eating cues, and exercise or activity cues - it's very

diverse," Yoo said.

The rising and the

setting

of the sun is still the primary

influence on circadian rhythms, but other systems have steadily

grown in scientific inquiry.

A large body of work has

demonstrated that diet is a key extrinsic cue interacting with the

intrinsic clocks, including Dr. Satchidananda Panda's work on

time-restricted feeding, or how the

time of eating impacts health (The

Complete Guide to the Science of Fasting.)

Overall, it is now clear that circadian rhythms perform a systemic

role to orchestrate all aspects of physiology in our body, including

vital organ functions, metabolism, immunity, cognition and more.

Yoo's research has been

expanding the field,

partnering with a chronic pain specialist

to study the rhythms of pain in patients.

Work is also being

conducted on the role of the light-dark cycle and

disruptions in circadian rhythms by jet lag

on cancer growth. Such studies of circadian rhythms under normal and

disease conditions are teaching us important new insights that can

be harnessed for lifestyle changes (when to eat, how much to sleep)

and for discovering drugs that can help modulate circadian rhythms.

And there is plenty more

research to be done in virtually all aspects of human health and

disease.

The Takeaway -

Why Does Awareness of Your Circadian Rhythms Matter?

An awareness of the fundamentals of circadian rhythms can have both

short- and long-term effects on health.

"Lifestyle changes

are the best gift you can give yourself," Chen said. "If you

manage your lifestyle, medicine and technology could all be

secondary for a long time during your life."

In the short-term, animal

and human studies suggest that following lifestyle practices that

support healthy circadian rhythms could support cognition,

alertness, coordination, cardiovascular efficiency, the immune

system, consistent bowel movements, and sleep.

In the long-term, there

is evidence supporting

reduced risk of chronic diseases

and an extended healthspan.

"It's a chronic

process to maintain it," Chen said. "The effects may not

manifest in a few days, but over time, the benefits will be

enormous."

So how can you best

pursue a lifestyle in sync with your circadian rhythms?

The first thing you need

to do is pay attention to your natural rhythms. Circadian rhythms,

while generally built on the same foundation,

vary from person to person because

of age, genetic, and environmental differences.

Morning people like

mornings better. Night people like nights better.

Paying attention to our

natural inclinations, also known as our individual "chronotypes,"

allows us to incorporate the best practices from circadian rhythm

research while also acknowledging that there's no one-size-fits-all

approach.

The second best thing you can do for yourself is establish a

consistent routine - and that means seven days per week.

Yoo discussed the idea of

"weekend jet lag," (or "social jet lag") where people throw off

their rhythm with atypical habits, for example, eating and going to

sleep later, waking up later, and exercising at different times of

the day. This can cause the same kind of negative effects as

changing timezones.

The closer and more

consistently you can keep your routine, the better your body will

run on that routine.

Lastly, incorporate the research, which we present in detail for

sleep, eating, and exercise, below. Many of the lifestyle changes

the studies suggest - for example, that

eating right before sleeping is a bad idea

- have little downside.

Eating bigger meals

earlier in the day and smaller meals in the evening is easy enough

to try. Likewise, sleeping on a standard schedule, with seven to

eight hours of sleep per night, has no apparent downside.

At worst, you'll feel

rested, and at best you'll improve your prospects for a healthy

life.

Best Practices

- Some Sleeping, Eating, and Exercise Tips for a Healthy Lifestyle

Sleep

The most important thing you can do is keep your sleep and

waking times consistent and get enough sleep -

seven to nine hours is usually

considered the right amount for adults.

At this point the

scientific research on not getting enough sleep or having

disruptive sleep is conclusive:

It has a negative

impact on mood, focus, cognitive function, and ultimately is

linked to chronic disease.

What's more some

scientists suggest that circadian misalignment caused by social

jet lag may be a widespread phenomenon in the western world

contributing to health problems.

So when should you sleep? Typically the body begins to secrete

melatonin around 9:00 p.m.

This is the trigger

to shut things down and go rest. Melatonin secretion ends around

7:30 a.m., and during the day, there is virtually no melatonin

in the system.

Working around that

general window, adjusting for personal preferences based on your

natural inclinations, is key for avoiding sleep fragmentation

(waking throughout your sleep) and for maintaining optimal

health.

Finally, light is a factor. The light-dark cycle no longer is

the only influence on our system, since we now encounter

artificial light constantly - but it still plays a primary

role.

Getting plenty of

natural light early in the day and avoiding unnatural light (blue

light from screens, for instance) in the evening will

support circadian alignment.

Key Takeaway:

Get plenty of sleep,

and keep your sleep and waking timing consistent seven days per

week. If you have sleep debt, start paying it down now, before

it compromises your long-term health.

Eating

Generally speaking, studies suggests that eating your calories

earlier in the day is better.

Try to have your last

meal be a smaller intake of calories, and have it occur well

before your bedtime. If you can wrap things around 6:00 p.m. or

7:00 p.m. and give your body 12-14 hours to rest and restore,

you may see short- and long-term health benefits.

Part of the reason is that, at night, your liver clock will shut

down. It stops producing enzymes to convert calories to energy;

it's producing enzymes to store energy.

If you load in a

bunch of food, you're making it work overtime - and it's going

to store more than burn.

The other significant lifestyle decision you can make (beyond

eating a healthy diet) is to restrict the window during which

you eat.

While the data thus

far is restricted to animal studies, Dr. Panda's work suggests

that "time-restricted

feeding" is an easy and potentially beneficial

lifestyle change.

"What is optimal

depends on someone's goal," he says.

"But if the goal

is to improve overall health, then 8-9 hours might be better

to begin with, but in terms of sticking with it long term,

maybe 10-12 hours is practical."

Takeaway:

Eat more earlier in

the day, rather than later. Eat within a 10–12 hour window.

Exercise

While some research suggests that anaerobic performance peaks in

the afternoon, there doesn't appear to be a scientific consensus

on the relationship between circadian rhythm and exercise -

except that there are in fact molecular clocks in skeletal

muscle.

And like light and

eating, when you exercise likely plays a role in maintaining

healthy rhythms.

Takeaway:

Exercise often, and

save your anaerobic activities for later in the day.

If You

Remember One Thing - Final Thoughts on Circadian Rhythms

Distilled down, the research on circadian rhythms is fairly

straightforward.

"Your body clock is

designed to burn during the day, then restore or reprogram

during the night," Yoo said.

The better in sync to

that cycle you are, the less wear-and-tear on your circadian clock.

While the clock is

resilient, consistent disruption can cause long-term health issues.

"When you are young,

your body can take it," Yoo said.

"But it doesn't mean

that it's completely okay. It's like mileage: You're using up

your mileage by doing that kind of [arrhythmic] activity, and

that will create problems when your body clock is no longer

robust."

You're not shaving off

five years of your life from one late night of eating and drinking,

but the clock is there to protect and minimize the disruption to our

physiology.

Be kind to it and you may

well notice the benefits to your health...

|