|

|

|

Scientists have for the first time

created a functional human liver from

stem cells derived from skin

and blood and say their success points to a future where much-needed

livers and other transplant organs could be made in a laboratory.

He said however that while the technique looks "very promising" and represents a huge step forward,

Researchers around the world have been

studying stem cells from various sources for more than a decade,

hoping to capitalize on their ability to transform into a wide

variety of other kinds of cell to treat a range of health

conditions.

Countries across the world have a critical shortage of donor organs for treating patients with liver, kidney, heart and other organ failure.

Scientists are keenly aware of the need

to find other ways of obtaining organs for transplant.

Malcolm Allison, a stem cell expert at Queen Mary University of London, who was not involved in the research, said the study's results offered,

Takanori Takebe, who led

the study, told a teleconference he

was so encouraged by the success of this work that he plans similar

research on other organs such as the pancreas and lungs.

Chris Mason, a regenerative medicine expert at University College London said the greatest impact of iPS cell-liver buds might be in their use in improving drug development.

The suggestion from this new study is that mice transplanted with human iPS cell-liver buds might be used to test new drugs to see how the human liver would cope with them and whether they might have side-effects such as liver toxicity.

...in

A Petri Dish from NPR Website

Liver buds" grow in petri dishes. The rudimentary organs are about 5 mm wide,

or half the height of

a classic Lego block.

Yokohama City University Graduate School

of Medicine

Japanese scientists have cracked open a freaky new chapter in the sci-fi-meets-stem-cells era.

A group in Yokohama reported it has grown a primitive liver in a petri dish using a person's skin cells. The organ isn't complete. It's missing a few parts. And it will be years - maybe decades - before the technique reaches clinics.

Still, this rudimentary liver is the first complex, functioning organ to be grown in the lab from human, skin-derived stem cells.

When the scientists transplanted the organ into a mouse, it worked a lot like a regular human liver.

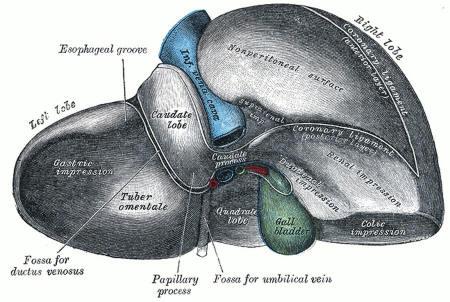

Not quite yet: A human liver contains bile ducts connecting to the gall bladder. The proto-livers made in the lab are missing these tubes. Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body

Several labs around the world have been trying to grow organs on plastic scaffolds, which offer a three-dimensional surface on which cells can stick.

This approach has been used to make tracheas from a person's own cells. And doctors have even transplanted these synthetic organs into a handful of patients.

But more complex organs - kidneys, pancreases and livers - have been elusive. So Takanori Takebe and a team at the Yokohama City University tried a more laid-back strategy: They let the cells build their own scaffold.

The team took some liver cells (made from a person's induced pluripotent stem cells) and then mixed them with two other cell types - one that makes blood vessels and one that builds connective tissue to hold an organ together.

Five days later, Takebe was "completely gobsmacked," by what he saw in the petri dish, he told reporters Tuesday, with the help of a translator. The cell mixtures had assembled into tiny 3-D structures that looked and acted like miniature livers, or "liver buds," as Takebe calls them. The proto-organs were only about 5 millimeters tall, or half the height of a Lego brick. But the liverettes built their own blood vessels, which allowed Takebe and his team to test-drive them in mice.

They plucked the liver buds from the petri dish and then connected them to blood vessels in a mouse. About 10 days later, the buds started working. They broke down human drugs and made blood proteins, as a regular liver would.

One proto-organ even saved a mouse from liver failure, Takebe and his colleagues report in the journal Nature.

The results are "extremely encouraging," says stem-cell scientist Stuart Forbes, from the University of Edinburgh.

First off, the organs are too small to be useful.

Doctors would need thousands of them to help a person with liver damage. And the little buds don't form a full liver. They're missing bile ducts, or the tubes that drain away toxins. Plus, Forbes says, there's still a big question about safety. Stem cells tend to form tumors.

And the current study doesn't look at the long-term effect of the transplanted liver.

|