|

by David Talbott and Wallace

Thornhill

May 05, 2006

from

Thunderbolts Website

It is happening for "no apparent reasons", scientists say, but the

comet Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 has been rapidly breaking apart,

provoking another round of second-guessing by astronomers.

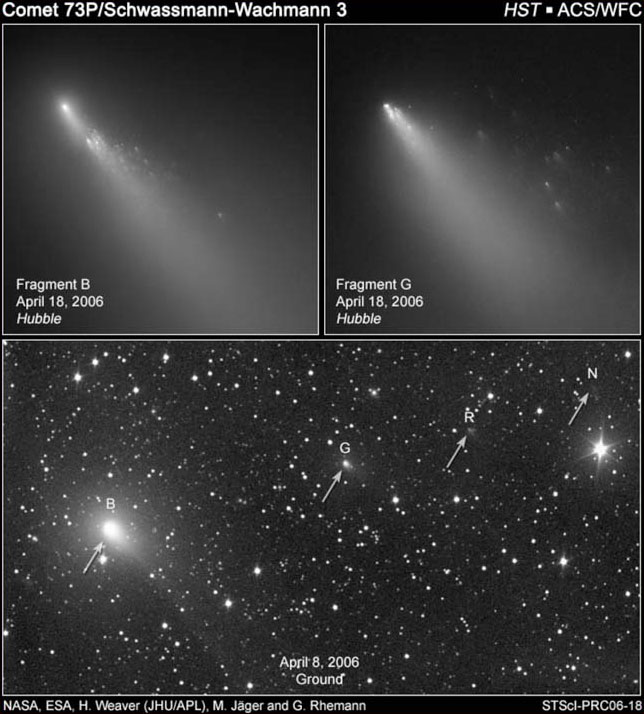

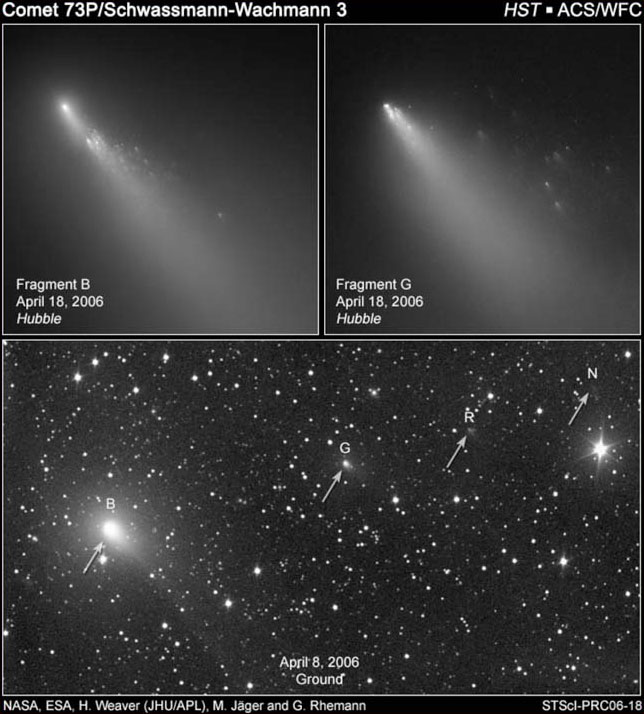

The images above, captured by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope,

are the best pictures yet of an event that has astronomers

scratching their heads. The comet Schwassmann-Wachmann 3,

otherwise known as Comet 73P, is disintegrating in front of their

eyes. But what is the cause of this extraordinary event? Not one of

the theoretical surmises offered so far has satisfied the community

of astronomers as a whole.

From all standard vantage points such an

event presents inherent - some would say insurmountable - dilemmas.

Schwassmann-Wachmann 3, first observed in 1930 and named

after its two German discoverers, completes an orbit every 5.4

years. Following its discovery it was little more than a footnote in

comet science until 1995. The first appearance of the comet that

year was so bright that astronomers hailed it as a new comet. But as

it turned out, the "newcomer" was Schwassmann-Wachmann 3,

presenting itself in more glorious dress than ever before, despite

the fact that conditions were not favorable.

It was 150 million miles away, but

shining hundreds of times more brightly than expected.

In early 1996 astronomers discovered

that the comet had fragmented into at least three pieces, an

occurrence clearly linked to the spectacular brightening, though no

one could say what caused the event.

It also appeared as if one or

more of the pieces was breaking into secondary fragments.

When the comet returned in 2000 it was again brighter than expected,

with indications that the disintegration was continuing - or even

accelerating. And now, with its most recent appearance, the best

Hubble images show dozens of fragments, suggesting the possibility

of complete dissolution in a single remaining passage around the

Sun.

Meanwhile, the "explanations" proposed for the comet's catastrophic

fate can only diminish confidence in today's comet science. Even in

the face of falsifying discoveries, the specialists appear unwilling

to reconsider their theoretical starting point.

One astronomer, from

the Sydney Observatory, offered this explanation of the comet's

fragmentation:

"It's like pouring hot coffee into a

glass that's been in the fridge. The glass shatters from the

shock".

But there is no rational comparison of

the two phenomena. Any explanation by resort to "thermal stress"

must provide for heat transfer rapidly through thousands of feet of

insulating material, something inconceivable even if you ignore the

deep freeze of the vacuum through which the comet is moving, with

its sunward face continually changing due to rotation.

Another astronomer, from University of Western Ontario, suggested,

"The most likely explanation is

thermal stress, with the icy nucleus cracking like an ice cube

dropped into hot soup".

All that this "explanation" requires is

a little home experiment. The ice cube will not shatter explosively,

or any way display effects comparable to the disintegration of

Schwassmann- Wachmann 3 - not even if dropped into boiling water.

It will melt. And no matter what a comet is composed of, the heat

transfer the "theory" implies for a mile-wide solid object is beyond

all reason.

In addition to citing possible "thermal stresses", the Hubble

Space Telescope website offers other possibilities as to

why comets might disintegrate so explosively:

"They can also fly apart from rapid

rotation of the nucleus, or explosively pop apart like corks

from champagne bottles due to the outburst of trapped volatile

gases".

But the centrifugal forces acting on

comet nuclei are close to zero. And to posit heating in the middle

of a mile-wide dirty ice cube is, again, scientifically indefensible.

Perhaps then, Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 "was shattered by a hit

from a small interplanetary boulder?" offered one of the astronomers

quoted above.

"But make that a series of

one-in-a-trillion hits", mused a critic of today's comet

science. "That way we can explain the continuing fragmentation

over years".

Comet science is indeed in trouble, and

it is particularly dismaying to see spokesmen for the Hubble site

announcing that their telescope may help to,

"reveal which of these breakup

mechanisms are contributing to the disintegration of 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann

3".

Neither NASA, nor the Hubble

folks in particular will find evidence for any of the "hypotheses"

offered, say the electrical theorists.

From an electrical viewpoint the periodic breakup of comets is no

surprise. Fragmentation and disintegration illustrate the same

dynamic forces observed in the "surprising" outbursts of comets.

Electrical outbursts and complete disintegration are merely matters

of degree in a discharging or

exploding capacitor, which is

exactly what an "active comet" is in the electrical interpretation.

A capacitor, one of the most commonly used devices in electrical

engineering, stores electrical charge between layers of insulating

material. And that is what a comet moving through regions of

different charge will do - it will store electric charge.

A comet

nucleus can be compared to the insulating material, the dielectric,

in a capacitor.

As charge is exchanged from the cometís

surface to the solar "wind" (actually an electrically active

plasma), electrical energy is stored in the nucleus in the form of

charge polarization. This can easily build up intense mechanical

stress in the comet nucleus, which may be released catastrophically.

And just as a capacitor can explode when its insulation suffers

rapid breakdown, a comet can do precisely the same.

As suggested by electrical theorist Wallace Thornhill,

"comets break up not because they

are chunks of ice 'warming' in the Sun, and not because they are

loose aggregations of smaller bodies, but because of electrical

discharge within the nucleus itself".

Schwassmann-Wachmann 3, first

observed in 1930 and named after its two German discoverers, has

never put on a spectacular display comparable to such "Great Comets"

of the twentieth century as Halley, Hale-Bopp, and Hyakutake.

It is

a short-period comet: for electrical theorists that means a

lower-voltage comet - and, as a rule, less drama.

Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 completes an orbit every 5.4 years.

Its path takes it from just beyond the orbit of Jupiter to inside

the orbit of Earth. But it does not visit the more remote regions of

the solar system, while the spectacular "Great Comets" spend long

periods adjusting in that more negative environment of the Sun's

domain before racing sunward.

What Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 does

exhibit, however, is a highly elliptical (elongated) orbit, so in

electrical terms that means more rapid transit through the Sun's

electric field and more intense stresses on the capacitor than would

be the case were the comet moving on a less eccentric path between

the regions of Jupiter's and Earth's orbits.

The comet is presently headed toward perihelion, or closest approach

to the Sun (within 87.3 million miles), on June 6, 2006. Well before then,

on May 12th it will pass within 7.3 million miles of Earth.

Though that is roughly 30 times the

distance of the Moon from Earth, many earthbound and space

telescopes should capture images of the comet in sufficient

resolution to provide additional critical tests of the electrical

model.

|