|

|

Anyone who has been closely following the geopolitical

situation over the last decade would not be in the least surprised

or baffled at why most of the information is now being withheld from

the public.

Objects in the heavens will be playing a

greater and greater role in events down here on the Big

Blue Marble over the next few years, if our hypotheses

is close to correct.

The masters of our world want more "hype and fear of the unknown".

World events are orchestrated for just that effect.

from

SOTT Website |

Jupiter - Our Cosmic Protector?

by Dennis Overbye

July 25, 2009

from

TheNewYorkTimes Website

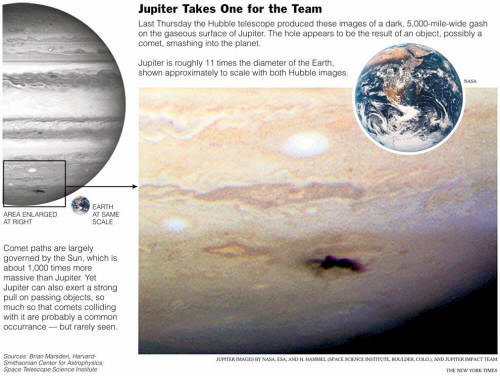

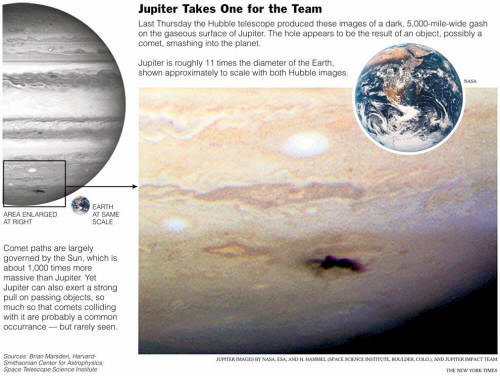

Jupiter Takes One for

the Team

An object, probably a comet that nobody

saw coming, plowed into the giant planetís colorful cloud tops

sometime Sunday, splashing up debris and leaving a black eye the

size of the Pacific Ocean.

This was the second time in 15 years that

this had happened. The whole world was watching when

Comet

Shoemaker-Levy 9 fell apart and its pieces crashed into Jupiter in

1994, leaving Earth-size marks that persisted up to a year.

Thatís Jupiter doing its cosmic job, astronomers like to say. Better

it than us.

Part of what makes the Earth such a nice place to live,

the story goes, is that Jupiterís overbearing gravity acts as a

gravitational shield deflecting incoming space junk, mainly comets,

away from the inner solar system where it could do for us what an

asteroid apparently did for the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Indeed, astronomers look for similar configurations

- a giant outer

planet with room for smaller planets in closer to the home stars - in other planetary systems as an indication of their hospitableness

to life.

Anthony Wesley, the Australian amateur astronomer who first noticed

the mark on Jupiter and sounded the alarm on Sunday, paid homage to

that notion when he told The Sydney Morning Herald,

"If anything like that had hit the

Earth it would have been curtains for us, so we can feel very

happy that Jupiter is doing its vacuum-cleaner job and hovering

up all these large pieces before they come for us."

But is this warm and fuzzy image of the

King of Planets as

father-protector really true?

"I really question this idea," said

Brian G. Marsden of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for

Astrophysics, referring to Jupiter as our guardian planet.

As the former director of the

International Astronomical Unionís Central Bureau for Astronomical

Telegrams, he has spent his career keeping track of wayward objects,

particularly comets, in the solar system.

Jupiter is just as much a menace as a savior, he said. The big

planet throws a lot of comets out of the solar system, but it also

throws them in.

Take, for example,

Comet Lexell, named after the Swedish astronomer

Anders Lexell. In 1770 it whizzed only a million miles from the

Earth, missing us by a cosmic whisker, Dr. Marsden said. That comet

had come streaking in from the outer solar system three years

earlier and passed close to Jupiter, which diverted it into a new

orbit and straight toward Earth.

The comet made two passes around the Sun and in 1779 again passed

very close to Jupiter, which then threw it back out of the solar

system.

"It was as if Jupiter aimed at us

and missed," said Dr. Marsden, who complained that the comet

would never have come anywhere near the Earth if Jupiter hadnít

thrown it at us in the first place.

Hal Levison, an astronomer at the

Southwest Research Institute, in Boulder, Colo., who studies the

evolution of the solar system, said that whether Jupiter was menace

or protector depended on where the comets came from.

Lexell, like

Shoemaker Levy 9 and

probably the truck that just hit Jupiter, most likely came from an

icy zone of debris known as

the Kuiper Belt, which lies just outside

the orbit of Neptune, he explained. Jupiter probably does increase

our exposure to those comets, he said.

But Jupiter helps protect us, he said, from an even more dangerous

band of comets coming from the so-called

Oort Cloud, a vast

spherical deep-freeze surrounding the solar system as far as a

light-year from the Sun.

Every once in a while, in response to

gravitational nudges from a passing star or gas cloud, a comet is

unleashed from storage and comes crashing inward.

Jupiterís benign influence here comes in two forms. The cloud was

initially populated in the early days of the solar system by the

gravity of Uranus and Neptune sweeping up debris and flinging it

outward, but Jupiter and Saturn are so strong, Dr. Levison said,

that, first of all, they threw a lot of the junk out of the solar

system altogether, lessening the size of this cosmic arsenal.

Second, Jupiter deflects some of the

comets that get dislodged and fall back in, Dr. Levison said.

"Itís a double anti-whammy," he

said.

Asteroids pose the greatest danger of

all to Earth, however, astronomers say, and here Jupiterís influence

is hardly assuring.

Mostly asteroids live peacefully in the asteroid

belt between Mars and Jupiter, whose gravity, so the standard story

goes, keeps them too stirred to coalesce into a planet but can cause

them to collide and rebound in the direction of Earth.

Thatís what happened, Greg Laughlin of the University of California

at Santa Cruz, said, to a chunk of iron and nickel about 50 yards

across roughly 10 million to 100 million years ago.

The result is a

hole in the desert almost a mile wide and 500 feet deep in northern

Arizona, called

Barringer Crater.

A gift, perhaps, from our friend

and lord, Jupiter.

Comment

from

Sott Website

Regarding the claim that Jupiter

"protects us from an even more dangerous band of comets coming

from the so-called Oort Cloud", let's see what Clube and Napier,

British astronomers and writers of The Cosmic Serpent, have to

say:

The giant comets normally reside far beyond the planets, in a

spherical cloud surrounding the Sun, called the Oort cloud.

There is also evidence for a flattened disk of comets closer to

the inner solar system, called the Edgeworth/Kuiper belt. What

prompts members of either of these comet repositories to enter

the realm of the planets? Clube and Napier suggest a galactic

influence.

The solar system periodically passes

through the plane of the galaxy as the Sun (and the solar system

with it) orbits the galactic center.

Each passage may dislodge

giant comets and divert them closer to the Sun. The outer

planets, particularly Jupiter, may then perturb some of these

giant comets into orbits which enter the inner solar system.

These comets, stressed both by

gravity and by heat from the sun, may fragment into a cloud of

smaller objects with dynamically similar orbits.

Chiron offers a good example of a giant comet as called for by

Clube and Napier's giant comet hypothesis. Chiron is somewhere

between 148 and 208 kilometers in diameter.

Currently Chiron's

unstable "parking orbit" lies mostly between Saturn and Uranus.

Chiron may end up injected into the inner solar system within a

hundred thousand years, or ejected from the solar system on a

similar time scale.

It is also possible that Chiron has already

visited the inner solar system.

The Taurid complex and the Kreutz sungrazer group are two

families of objects which most likely represent the fragmented

remains of two giant comets in the current era.

SOHO has

recently discovered many new members of the Kreutz group which

were previously unknown.

The Kreutz progenitor was injected into a retrograde orbit and

attained the sungrazing state at a high inclination to the

ecliptic. Hence the debris of its "children" does not pose a

threat to the Earth. The Taurid progenitor on the other hand

ended up in a short-period low-inclination prograde orbit.

This

is why the Earth can encounter its debris with potentially

calamitous results.

What would happen should the Earth pass through the orbit of a

disintegrating giant comet just before or after the comet passes

that same point? Since larger fragments tend to cluster close to

the nucleus of the comet, chances would increase that the Earth

would be bombarded by these larger fragments.

The severity of this comet fragment

shower would far exceed any ordinary meteor shower.

Not only

would "shooting stars" and bright fireballs caused by small

debris appear, but so too would large airbursts and possibly

ground impacts.

These would result in significant destruction

should they occur over an inhabited area.

If a large enough

fragment struck in the ocean - say, 200 meters or so in

diameter - it would raise tsunamis even at a great distance

that would sweep away coastal habitations.

Duncan Steel, a colleague of Clube and Napier, refers to this

process as coherent catastrophism.

Widespread destruction

derives from the coherent arrival of many impactors within a few

days, as opposed to the sporadic arrival of objects spread

randomly in space.

The shower repeats for a period of years

until the cometary orbit precesses so that the Earth no longer

encounters the dense part of the debris field.

(Of course, sporadic debris

unrelated to the disintegrating comet may impact at any time as

well.)

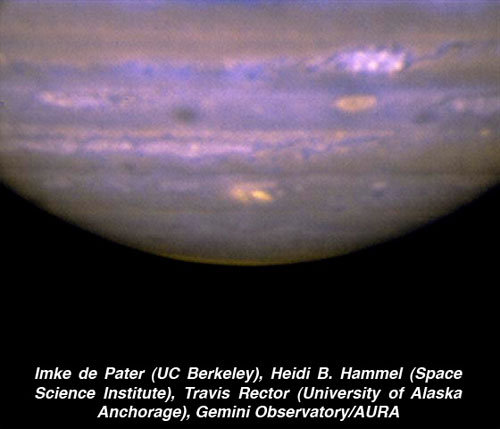

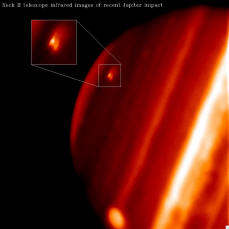

New Image of Jupiter Impact in Infrared

by Nancy Atkinson

July 23, 2009

from

UniverseToday Website

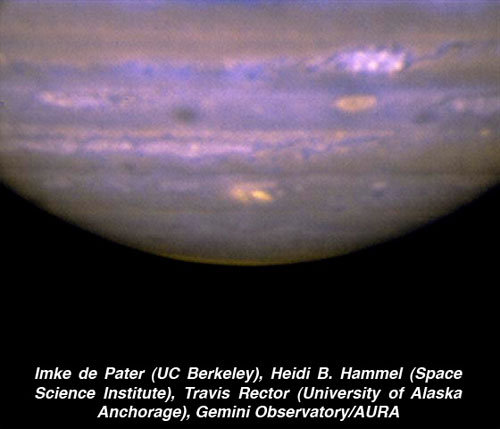

This mid-infrared composite image was obtained

with the Gemini North

telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawai'i,

on 22 July at ~13:30 UT with the

MICHELLE mid-infrared spectrograph/imager.

The impact site is the

bright yellow spot

at the center bottom of Jupiter's disk.

After getting whacked unexpectedly by a small comet or asteroid,

Jupiter is sporting a "bruise," which has been big news this week.

In visible wavelengths, the impact site appears as a black spot.

But

in a new image taken in near infrared by the Gemini North telescope

on Mauna Kea, Hawai'i, the spot shows up in spectacular glowing

yellow.

"We utilized the powerful mid-infrared capabilities of the Gemini

telescope to record the impact's effect on Jupiter's upper

atmosphere," said Imke de Pater from the University of California,

Berkeley.

"At these wavelengths we receive thermal radiation (heat)

from the planet's upper atmosphere. The impact site is clearly much

warmer than its surroundings, as shown by our image taken at an

infrared wavelength of 18 microns."

As Universe Today reported earlier, this new spot on Jupiter was

first seen by Australian amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley on July

19th.

This set off a flurry of activity as the large ground based

observatories have imaged Jupiter in attempt to learn more about the

impact and the object that struck Jupiter.

Astronomers now say the

object was likely a small comet or asteroid, just a few hundreds of

meters in diameter. Such small bodies are nearly impossible to

detect near or beyond Jupiter unless they reveal cometary activity,

or, as in this case, make their presence known by impacting a giant

planet.

In infrared, the impact site shows up in remarkable detail.

"The

structure of the impact site is eerily reminiscent of the larger

Shoemaker-Levy 9 sites 15 years ago," remarked Heidi Hammel

(Space

Science Institute), who was part of the team that supported the

effort at Gemini.

In 1994, Hammel led the Hubble Space Telescope

team that imaged Jupiter when it was pummeled by a shattered comet.

"The morphology is suggestive of an arc-like structure in the

feature's debris field," Hammel noted.

The Gemini images were obtained with the MICHELLE

spectrograph/imager, yielding a series of images at 7 different

mid-infrared wavelengths.

Two of the images (8.7 and 9.7 microns)

were combined into a color composite image by Travis Rector at the

University of Alaska, Anchorage to create the final false-color

image.

By using the full set of Gemini images taken over a range of

wavelengths from 8 to 18 microns, the team will be able to

disentangle the effects of temperature, ammonia abundance, and upper

atmospheric aerosol content.

Comparing these Gemini observations

with past and future images will permit the team to study the

evolution of features as Jupiter's strong winds disperse them.

"The Gemini support staff made a heroic effort to get these data,"

said de Pater.

"We were on the telescope observing within 24 hours

of contacting the observatory." Because of the transient nature of

this event, the telescope was scheduled as a "Target of Opportunity"

and required staff to react quickly to the request."

Backyard Astronomer spots Big Bang on

Jupiter

by Asher Moses

July 21, 2009

from

SMH Website

An amateur Australian astronomer has set the space-watching world on

fire after discovering that a rare comet or asteroid had crashed

into Jupiter, leaving an impact the size of Earth.

Anthony Wesley, 44, a computer programmer from Murrumbateman, a

village north of Canberra, made the discovery about 1am yesterday

using his backyard 14.5-inch reflecting telescope.

The impact would have occurred no more than two days earlier and

will only be visible for another few days.

Within hours, his images had spread across the internet on science

websites.

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory confirmed the discovery at 9pm

yesterday using its large infrared telescope at the summit of Mauna

Kea in Hawaii.

The only other time astronomers have discovered evidence of a space

object having hit Jupiter was when the

Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet

collided with the giant planet in July, 1994.

That event was also the first direct observation of two objects

colliding in space.

Glenn Orton, the NASA scientist who confirmed Wesley's discovery,

said:

"We are extremely lucky to be seeing Jupiter at exactly the

right time, the right hour, the right side of Jupiter to witness the

event. We couldn't have planned it better."

Orton said he was not yet sure whether the object that hit Jupiter

was a comet, asteroid or some other piece of space junk.

But the

impact mark is about the size of the Earth.

"It's been a whirlwind of a day and this, on the anniversary of the

Shoemaker-Levy 9 and Apollo anniversaries, is amazing," he said.

To most people the image is unremarkable and appears as little more

than a scar on Jupiter's vast gas surface.

Leigh Fletcher, an astronomer who worked with Orton on confirming

the discovery last night, said:

"These are the most exciting

observations I've seen in my five years of observing the outer

planets."

Wesley said in a phone interview that documenting these sorts of

impacts was the only way to get new data on how the solar system

formed and what planets such as Jupiter are made of, as the impact

throws up debris that would otherwise be invisible when looking

through a telescope from Earth.

The collision also allows astronomers to examine Jupiter's role in

cleaning up space debris in the solar system.

"If anything like that had hit the Earth it would have been curtains

for us, so we can feel very happy that Jupiter is doing its

vacuum-cleaner job and hovering up all these large pieces before

they come for us," he said.

"An impact event like this, even just knowing how often they happen,

gives you some idea of how much debris is left over from the solar

system when it formed and how quickly Jupiter is vacuuming up the

remains of the bits and pieces floating around in the solar system."

Mike Salway, who runs the Australian amateur astronomy community

website

iceinspace.com.au, said astronomers around the world were

raving about the discovery.

"Amateur astronomers are all over it at the moment - they all had

their telescopes out last night looking for it," he said.

Wesley, who has been keen on astronomy since he was a child, said

telescopes and other astronomy equipment were so inexpensive now

that the hobby had become a viable pastime for just about anybody.

His own equipment cost about $10,000.

In many cases, particularly with planets such as Jupiter,

professional space watchers were turning to amateurs to provide them

with new discoveries.

"A lot of the professional astronomers have access to large scopes

but those scopes are in demand for all sorts of other jobs and you

just can't afford to tie up a large telescope worth millions of

dollars looking at Jupiter every night," Wesley said.

"These large telescopes only get built because of the interests of

the consortium parties, and those interests need to be attended to,

so it's really left to amateurs who've got no fixed agenda to image

whatever they find interesting."

A new Bright Spot on Venus

by Dr. Emily Baldwin

ASTRONOMY NOW

July 21, 2009

from

AstronomyNow Website

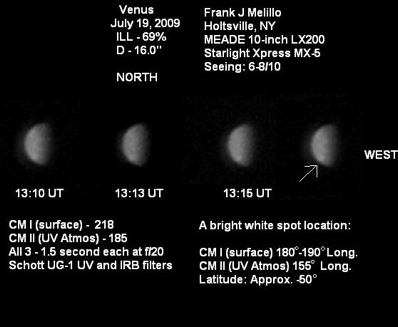

An intense bright spot has appeared in the clouds of Venus. Could it

be associated with volcanic activity on the surface?

The Solar System is breaking out in spots. First Jupiter took a

smack from a passing asteroid or comet, manifesting as a dark scar

in the Jovian atmosphere, and now Venus is sporting a brilliant

white spot in its southern polar region.

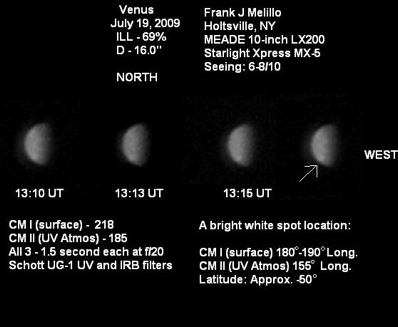

In an alert to fellow amateur astronomers, Venus observer Frank Melillo reports on his images captured on 19 July:

"I have seen

bright spots before but this one is an exceptional bright and quite

intense area."

Venus' bright spot as captured by

Frank Melillo from New York.

Image

courtesy Frank Melillo.

He suggests that it could be explained as an atmospheric effect,

but

could it be a sign of volcanic activity at the planet's surface?

Venus is covered in a thick cloak of clouds which prevents any

visible observation of the surface.

Instead, radar is used to map

the surface, but volcanic activity has never been observed directly.

"A volcanic eruption would be nice, but let's wait and find out!"

says Venus specialist Dr Sanjay Limaye of the University of

Wisconsin.

"An eruption would have to be quite energetic to get a

cloud this high."

Furthermore, at a latitude of 50 degrees south,

the spot lies outside the region of known volcanoes on Venus.

Melillo comments that the spot will not be seen again as intense as

it is now, thanks to the rapid rotation of the planet's atmosphere.

"I hope that someone will image Venus on Thursday when this part of

the atmosphere is facing us again," he says.

Further observations will help shed light on the genesis of the

bright spot and how it evolves as the atmosphere churns over.

Jupiter Collision a Warning Call to Earth

by Peter N. Spotts

Staff writer of The Christian Science

Monitor

July 21, 2009

from

ChristianScienceMonitor Website

The list of cosmic objects that could hit Earth is growing.

Scientists study satellite 'tractors' and nuclear weapons as ways to

divert asteroids headed our way.

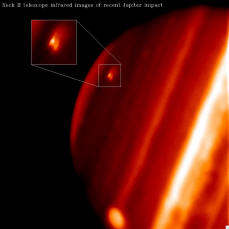

This detail image

shows a large impact

shown on the bottom

left on Jupiter's south polar region captured on July 20,

by NASA's Infrared

Telescope Facility in Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

Infrared Telescope Facility/Handout/JPL/NASA/Reuters

When an object smacked into Jupiter over the weekend, giving

astronomers their best cosmic-collision show since the comet

Shoemaker-Levy 9 in 1994, the giant gas ball of a planet took the

poke like the Pillsbury Dough Boy.

For all its scientific interest, however, the collision also serves

as a stark reminder that the solar system remains a shooting gallery

Ė with Earth, as well as Jupiter, on the wrong side of the firing

line.

The object's signature on Jupiter's cloud tops initially was

discovered by Australian amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley as he

gathered digital images of the giant planet through his 14.5-inch

telescope.

After alerting other astronomers to what appeared to be a

"scar" in the cloud tops similar to those generated by the pieces of

Shoemaker-Levy 9, NASA scientists trained a 3-meter (9.8-foot)

infrared telescope on the planet and got a good look at the scar.

"It could be the impact of a comet," according to Glenn Orton, a

scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena,

Calif., in a statement yesterday.

"But we don't know for sure yet."

When it comes to objects Earthlings should keep an eye on, the

catalog scientists have amassed is swelling.

Since 1995, astronomers associated with 10 search projects have

discovered more than 6,200 near-Earth asteroids of all sizes,

according to data from JPL. Some 784 are at least a kilometer (0.62

miles) across or larger.

Just over 1,000 of the total have been

deemed "potentially hazardous" Ė those that pass Earth at a distance

of less than 4.7 million miles.

And while the biggest ones have the potential to inflict the most

damage, scientists are gaining a new appreciation of the punch even

small ones can deliver.

Two and a half years ago, scientists at Sandia National Laboratories

in Albuquerque, N.M., conducted advanced supercomputer simulations

of the

June 1908 event over Siberia that flattened and scorched

trees over a region 30 miles across.

Estimates put the explosive

clout of the air burst from either a meteor or comet fragment at

between 10 and 20 megatons.

-

The good news: Calculations on Sandia's supercomputer, in 3-D, push

that explosive yield down to between three and five megatons.

-

The

bad news: The calculations also indicated that the asteroid or comet

fragment was much smaller than previously estimated.

There are more

small asteroids hurtling around us than large ones.

Sometimes they can seem to come out of nowhere.

Last October, astronomers detected an asteroid an estimated two to

five meters across. Some 21 hours later, it entered the atmosphere

over northern Sudan sprinkling the Nubian desert with meteorites.

The object's blast was estimated at roughly 1,000 tons of TNT.

For asteroid specialists, this was a live-fire test of protocols

they'd developed to alert astronomers to monitor the object to

refine orbital and impact-location estimates Ė and to alert national

authorities that a direct hit was on the way.

The incident "underscored the successful evolution of the Near-Earth

Object Program's discovery and orbit-prediction process," wrote JPL

scientists Steve Chesley, Paul Chodas, and Don Yeomans in a

post-event report on the incident.

The goal, of course, is to spot these objects and produce highly

refined orbit estimates in time to take defensive action, if

necessary.

And what might that action look like?

In a lengthy analysis of options that earned him a newly-minted PhD

in aeronautical engineering from the University of Glasgow, Joan Pau

Sanchez Cuartielles sorts through several approaches ranging from

detonating a small nuclear bomb near an asteroid to using a

modest-sized satellite as a kind of tractor that tugs the asteroid

into a less dangerous orbit, connected to the asteroid by their

mutual gravity.

The stand-off nuclear option (with an explosive yield tailored to

the mass and density of the asteroid) turned out to be the most

effective, although politically troublesome.

The gravity tug could

be effective with long lead times, or if the goal is to nudge an

asteroid just enough to ensure it avoids a gravitational sweet spot,

or keyhole, that would put it on a collision course with Earth

decades into the future.

Jupiter sports new 'bruise' from impact

by Lisa Grossman

21 July 2009

from

NewScientist Website

Something has smashed into Jupiter, leaving behind a black spot in

the planet's atmosphere, scientists confirmed on Monday.

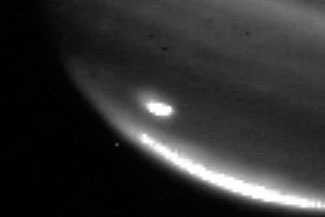

|

|

|

|

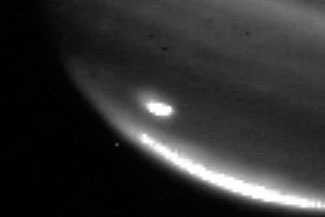

Infrared observations

taken at the Keck II telescope in Hawaii

reveal a bright spot

where the impact occurred.

The spot looks black

at visible wavelengths

(Image: Paul Kalas/Michael

Fitzgerald/Franck Marchis/LLNL/UCLA/UC Berkeley/SETI Institute)

|

Amateur

astronomer Anthony Wesley snapped this image of the new

black spot (near the top of Jupiter's disc) on Sunday,

just after discovering it

(Image:

Anthony Wesley)

|

This is only the second time such an impact has been observed.

The

first was almost exactly 15 years ago, when more than 20 fragments

of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 collided with the gas giant.

"This has all the hallmarks of an impact event, very similar to

Shoemaker-Levy 9," said Leigh Fletcher, an astronomer at NASA's Jet

Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California.

"We're all extremely

excited."

The impact was discovered by amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley in

Murrumbateman, Australia at about 1330 GMT on Sunday.

Wesley noticed

a black spot in Jupiter's south polar region (see above image) Ė but he

very nearly stopped observing before he saw it.

"By 1am I was ready to quit... then changed my mind and decided to

carry on for another half hour or so," he wrote in his observation

report.

Initially he suspected he was seeing one of Jupiter's moons

or a moon's shadow on the planet, but the location, size and speed

of the spot ruled out that possibility.

'Stroke of luck'

After checking images taken two nights earlier and not seeing the

spot, he realized he had found something new and began emailing

others.

Among the people he contacted were Fletcher and Glenn Orton, also at

JPL.

They had serendipitously scheduled observing time on NASA's

InfraRed Telescope Facility in Hawaii for that night.

"It was a fantastic stroke of luck," Orton told

New Scientist.

Their team began observations at about 1000 GMT on 20 July, and

after six hours of observing confirmed that the spot was an impact

and not a weather event.

"It's completely unlike any of the weather phenomena that we observe

on Jupiter," Orton says.

Splash

The first clue was a near-infrared image of the upper atmosphere

above the impact site.

An impact would make a splash like a stone

thrown into a pool, scattering material in the atmosphere upwards.

This material would then reflect sunlight, appearing as a bright

spot at near-infrared wavelengths.

And that's exactly what the team saw.

"Our first image showed a

really bright object right where that black scar was, and

immediately we knew this was an impact," Orton says.

"There's no

natural phenomenon that creates a black spot and bright particles

like that."

Supporting evidence came from measurements of Jupiter's temperature.

Thermal images also showed a bright spot where the impact took

place, meaning the impact warmed up the lower atmosphere in that

area.

The researchers have also found hints of higher-than-normal amounts

of ammonia in the upper atmosphere. Extra ammonia had been churned

up by the previous Shoemaker-Levy comet impact.

Exotic chemistry

The Shoemaker-Levy impact also introduced some exotic chemistry into

Jupiter's atmosphere. The energy from the collision fused some of

the original atmospheric components into new molecules, such as

hydrogen cyanide.

Scientists hope this new impact has done the same thing, since that

would allow them to follow the new materials and learn how the

atmosphere moves with time.

So what was the impactor?

"Not a clue," Orton says.

He speculates

that it could have been a block of ice from somewhere in Jupiter's

neighborhood, or a wandering comet that was too faint for

astronomers to detect before the impact.

"We don't know if the impact was produced by a comet or an

asteroid," agrees Franck Marchis, an astronomer at the University of

California, Berkeley, and the SETI Institute, who was part of a team

that observed the spot on Sunday with the Keck Observatory in Hawaii.

If the object was large enough to be visible before

impact, current surveys of asteroids may not have been looking in

the right direction to find it, he says, adding that future surveys

will spot more of the solar system's uncatalogued objects.

Asteroid or comet

Spectra collected by various observatories may help identify what

the impactor was, since a large amount of water at the impact

location would hint at a comet as the source.

"We will also compare

the observations with those collected during [Shoemaker-Levy 9] 15

years ago," since that was a known comet, Marchis says.

Without having seen it, scientists can't tell how large the object

was.

"But the impact scar we're seeing is about the same size as one

of Jupiter's big storms, Oval BA, Fletcher told New Scientist.

"That, I believe, is about the size of the Earth."

Marchis says Jupiter may be protecting Earth from getting hit by

such objects.

"The solar system would have been a very dangerous

place if we did not have Jupiter," he told New Scientist.

"We should

thank our Giant Planet for suffering for us. Its strong

gravitational field is acting like a shield protecting us from

comets coming from the outer part of the solar system."

Stephen Hawking - "Asteroid Impacts

Biggest Threat to Intelligent Life in the Galaxy"

by Casey Kazan with Rebecca

Sato

June 26, 2009

from

DailyGalaxy Website

Asteroids, Stephen Hawking believes, that one of the major

factors in the possible scarcity of intelligent life in our galaxy

is the high probability of an asteroid or comet colliding with

inhabited planets.

We have observed, Hawking points out in

Life in the Universe, the collision of a comet,

Shoemaker-Levy 9, with Jupiter

(below), which produced a series of enormous fireballs, plumes many

thousands of kilometers high, hot "bubbles" of gas in the

atmosphere, and large dark "scars" on the atmosphere which had

lifetimes on the order of weeks.

It is thought the collision of a rather

smaller body with the Earth, about 70 million years ago, was

responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs.

A few small early

mammals survived, but anything as large as a human, would have

almost certainly been wiped out.

Through Earth's history such collisions occur, on the average every

one million year. If this figure is correct, it would mean that

intelligent life on Earth has developed only because of the lucky

chance that there have been no major collisions in the last 70

million years.

Other

planets in the galaxy, Hawking believes, on which life has

developed, may not have had a long enough collision free period to

evolve intelligent beings. Other

planets in the galaxy, Hawking believes, on which life has

developed, may not have had a long enough collision free period to

evolve intelligent beings.

"The threat of the Earth being hit

by an asteroid is increasingly being accepted as the single

greatest natural disaster hazard faced by humanity," according

to Nick Bailey of the University of Southampton's School of

Engineering Sciences team, who has developed a threat

identifying program.

[Image right - Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

collision with Jupiter]

The team used raw data from multiple

impact simulations to rank each country based on the number of times

and how severely they would be affected by each impact.

The software, called

NEOimpactor (from NASA's

"NEO" or Near Earth Object program), has been specifically

developed for measuring the impact of 'small' asteroids under one

kilometer in diameter.

Early results indicate that in terms of population lost, China,

Indonesia, India, Japan and the United States face the greatest

overall threat; while the United States, China, Sweden, Canada and

Japan face the most severe economic effects due to the

infrastructure destroyed.

The top ten countries most at risk are:

-

Brazil

-

China

-

Indonesia

-

India

-

Italy

-

Japan

-

Nigeria

-

Philippines

-

United Kingdom

-

United States

"The consequences for human

populations and infrastructure as a result of an impact are

enormous," says Bailey.

"Nearly one hundred years ago a

remote region near the Tunguska River witnessed the largest

asteroid impact event in living memory when a relatively small

object (approximately 50 meters in diameter) exploded in

mid-air.

While it only flattened unpopulated

forest, had it exploded over London it could have devastated

everything within the M25. Our results highlight those countries

that face the greatest risk from this most global of natural

hazards and thus indicate which nations need to be involved in

mitigating the threat."

What would happen to the human species

and life on Earth in general if an asteroid the size of the one that

created the famous

K/T Event of 65 million years ago

at the end of the Mesozoic Era that resulted in the extinction of

the dinosaurs impacted our planet.

As Stephen Hawking says,

the

general consensus is that any comet or asteroid greater than 20

kilometers in diameter that strikes the Earth will result in the

complete annihilation of complex life - animals and higher plants.

(The

asteroid Vesta, for example, one of

the destinations of the

Dawn Mission, is the size of

Arizona).

How many times in our galaxy alone has life finally evolved to the

equivalent of our planets and animals on some far distant planet,

only to be utterly destroyed by an impact? Galactic history suggests

it might be a common occurrence.

The first this to understand about the K/T event is that is was

absolutely enormous: an asteroid (or comet) six to 10 miles in

diameter streaked through the Earth's atmosphere at 25,000 miles an

hour and struck the Yucatan region of Mexico with the force of 100

megatons - the equivalent of one Hiroshima bomb for every person

alive on Earth today. Not a pretty scenario!

Recent calculations show that our planet would go into another

"Snowball Earth" event like the one that occurred 600 million years

ago, when it is believed the oceans froze over (although some

scientists dispute this hypothesis -see link below).

While microbial bacteria might readily survive such calamitous

impacts, our new understanding from the record of the Earth's mass

extinctions clearly shows that plants and animals are very

susceptible to extinction in the wake of an impact.

Impact rates depend on how many comets and asteroids exist in a

particular planetary system. In general there is one major impact

every million years -a mere blink of the eye in geological time.

It also depends on how often those

objects are perturbed from safe orbits that parallel the Earth's

orbit to new, Earth-crossing orbits that might, sooner or later,

result in a catastrophic K/T or Permian-type mass extinction.

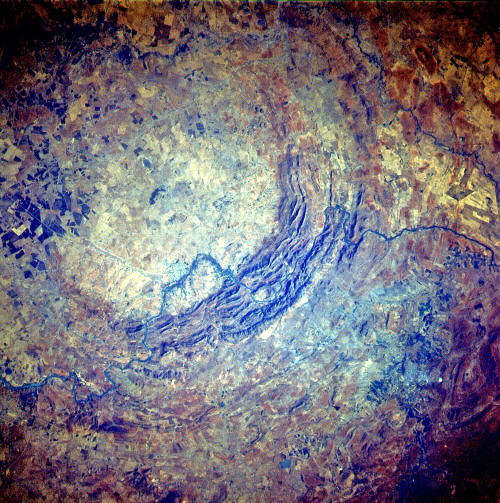

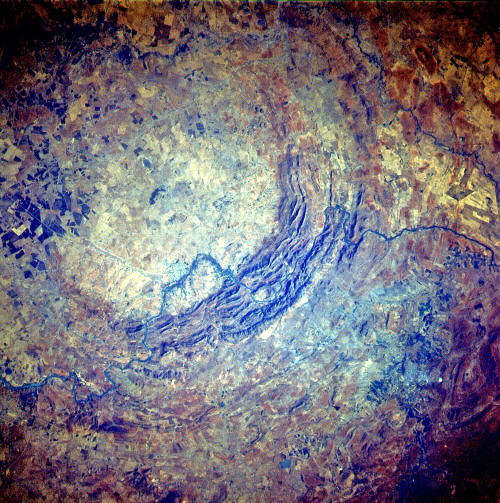

The

asteroid that hit Vredefort located

in the Free State Province of South Africa is one of the largest to

ever impact Earth, estimated at over 10 km (6 miles) wide, although

it is believed by many that the original size of the impact

structure could have been 250 km in diameter, or possibly larger

(though the Wilkes Land crater in Antarctica, if confirmed to have

been the result of an impact event, is even larger at 500 kilometers

across).

The town of Vredefort is situated in the

crater (image above).

Dating back 2,023 million years, it is the oldest astrobleme

found on earth so far, with a radius of 190km, it is also the most

deeply eroded.

Vredefort Dome Vredefort bears witness to the worldís

greatest known single energy release event, which caused devastating

global change, including, according to many scientists, major

evolutionary changes.

What has kept the Earth "safe" at least the past 65 million years,

other than blind luck is the massive gravitational field of

Jupiter, our cosmic guardian, with its stable circular orbit far

from the sun, which assures a low number of impacts resulting in

mass extinctions by sweeping up and scatters away most of the

dangerous Earth-orbit-crossing comets and asteroids

Jupiter increases risk of comet strike on Earth

by David Shiga

24 August 2007

from

NewScientist Website

Contrary to prevailing wisdom, Jupiter does not protect Earth from

comet strikes. In fact, Earth would suffer fewer impacts without the

influence of Jupiter's gravity, a new study says.

It could have

implications for determining which solar systems are most hospitable

to life.

Earth experienced an

especially heavy bombardment

of asteroids and

comets early in the solar system's history

(Illustration: Julian

Baum)

A 1994 study showed that replacing Jupiter with a much smaller

planet like Uranus or Neptune would lead to 1000 times as many

long-period comets hitting Earth.

This led to speculation that

complex life would have a hard time developing in solar systems

without a Jupiter-like planet because of more intense bombardment by

comets.

But a new study by Jonathan Horner and Barrie Jones of

Open

University in Milton Keynes, UK, shows that if there were no planet

at all in Jupiter's orbit, Earth would actually be safer from

impacts.

The contradictory results arise because Jupiter affects comets in

two different, competing ways.

Its gravity helps pull comets into

the inner solar system, where they have a chance of hitting Earth,

but can also clear away Earth-threatening comets by ejecting them

from the solar system altogether, via a gravitational slingshot

effect.

Tripled impacts

According to the new study, the worst scenario for Earth is when

Jupiter is replaced by a planet with about the mass of Saturn.

"[Such a planet] is fairly capable of putting things into an

Earth-crossing orbit, but still has some difficulty ejecting them,

so they will stay on an Earth-crossing orbit for a much longer

time," Horner told New Scientist.

The projected result was more than

three times as many impacts as in the real solar system.

So both the new study and the one from 1994 suggest that a smaller

planet in Jupiter's orbit would leave Earth worse off, although they

disagree about how much worse.

That may be because they differ on the source of the comets they

examine. Horner looked at objects coming from the Kuiper belt, a

region just beyond Neptune's orbit where many dormant comets reside.

The previous study, meanwhile, looked at the Oort cloud, a vast

collection of dormant comets extending hundreds of times further

from the Sun.

Ultimately, knowing what kinds of solar systems are safest from

bombardment could help in the search for alien life.

But, despite

the latest work, it is still unclear where we should be looking.

Asteroid threat

Alessandro Morbidelli of Nice Observatory in France, who studies

solar system dynamics, says neither Horner's analysis nor the earlier

study included the most important source of impacts - the asteroid

belt. About 95% of the impacts on Earth are due to asteroids, he

says.

He suspects that a smaller planet in place of Jupiter may lead to

fewer asteroid impacts.

"Given that near-Earth asteroids dominate

the impact rate, decreasing asteroid impacts might cause a decrease

in the overall bombardment rate of the Earth," he told New

Scientist.

Horner and Jones plan to extend their study to include asteroids,

but Morbidelli says there are even more factors to examine.

"You can

imagine solar systems where a much more massive and broader asteroid

belt is preserved - it would be difficult to live in that solar

system," he says.

"You can imagine giant planets migrating and

destroying an asteroid belt. There are so many factors it is

difficult to handle them all."

The results were presented Friday at the

European Planetary Science

Congress 2007 in Potsdam, Germany.

Video

Something Wicked this way comes

by

thesignsteam

October 30, 2007

from

YouTube Website

A

short film about

the Oort Cloud which surrounds our solar system and

the growing evidence that we belong to a binary star system.

|

Other

planets in the galaxy, Hawking believes, on which life has

developed, may not have had a long enough collision free period to

evolve intelligent beings.

Other

planets in the galaxy, Hawking believes, on which life has

developed, may not have had a long enough collision free period to

evolve intelligent beings.