|

by Nicole Mortillaro

December 13, 2013

from

GlobalNews Website

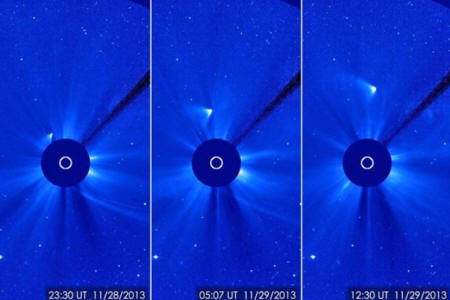

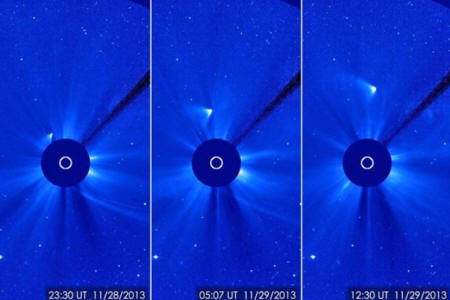

In this

combination of three images provided by NASA,

comet ISON appears as

a white smear heading up and away from the sun

on Thursday and

Friday, Nov. 28-29, 2013.

AP Photo/NASA

TORONTO

“Comet of the century!”

“To be seen in the daytime sky!”

These were only a few claims hyped by media upon the discovery of

Comet ISON in September 2012 by Russian astronomers Vitali Nevski

and Artyom Novichonok (a comet is usually named after its

discoverer, but this one was named after the project that discovered

it, the International Scientific Optical Network, ISON).

Of course,

none of those claims were true.

But

for scientists, it didn’t matter: ISON was a chance to peer back at

the very beginning of our solar system (read 'UPDATE

-

Comet ISON lives!').

Karl Battams, astrophysicist at the United States Naval

Research Laboratory (NRL)

in Washington, DC, and the voice of ISON throughout the comet’s

close pass, was happy with what was accomplished.

Battams led the

Comet ISON Observing Campaign.

Battams stressed that scientists never claimed ISON would put on the

show some believed would happen.

“Before us scientists even got to

put our word in, there were stories about the thing being

brighter than the full moon and ‘comet of the century,’ so that

made life difficult for us because what we… had to convey was

that this was a really, really exciting object, just not for the

reasons that you’ve been reading about.”

VIDEO: Comet ISON’s

pass around the sun (NASA)

And that reason was this: ISON was born out of

the Oort cloud - a

cloud that extends far beyond the orbit of Pluto - trillions of

kilometers away from the sun and which was born 4.5 billion years

ago.

And the fact that this comet was a sun-grazer

- a comet that

would pass very close to the sun - made it even more exciting.

Scientists would be able to see how this ancient piece of rock

interacted with solar radiation, learning about its composition and

characteristics.

This was ISON’s first pass, which meant that it had never been

bombarded by the sun’s radiation. Scientists wondered if the comet

would survive such a close pass - 1.2 million kilometers - above the

sun’s surface.

The sun is blazing hot at this distance, so hot that

it vaporizes almost everything.

“The very hardest rock you can imagine. If the comet was coated in

diamonds, the diamonds would instantly boil away and vaporize,”

Battams said.

All that heat and radiation was too much for the new comet.

Battam said that it may have been nicer to have had something in the

sky for people to see for themselves, but that doesn’t diminish how

important a role the comet played for scientists.

“We’ve gotten to watch this thing for such a long period of time

now, and we’ve recorded the largest and certainly the broadest data

set about a comet in history…

One of the key parts of studying a

comet is how were they put together. I think as any kid will tell

you, the best way to find out how a toy is put together is to rip it

apart,” Battams said, laughing.

“And as sad as it may seem, the sun ripped apart our little

Christmas present to see how it was put together, and that’s what

we’ve got to try to learn from.”

Astronomers will be analyzing the comet for months to come.

And they

have plenty of data to use.

“Scientifically, it’s just been absolutely incredible,” he said.

“I

think for me what I loved the most about this whole experience is

that we’ve pulled together not only professional observers from big

ground-based facilities, but we’ve got 13 different spacecraft

involved… Even stuff from Mars.

And to top it all off, the amateur

community has just been completely crucial to this whole process.

We’ve got an army of eyes around the world.”

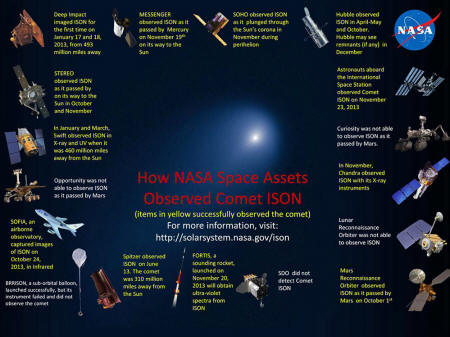

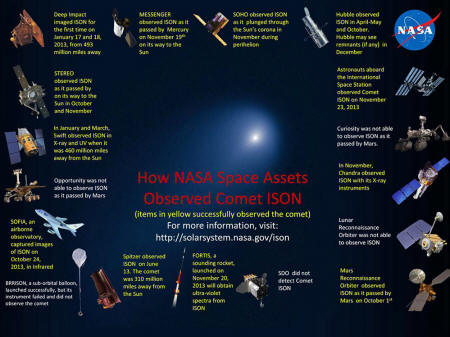

Various NASA observing campaigns.

(NASA)

Though Hubble is scheduled to image where ISON should be, Battam

doubts that there will be anything to see.

Two other telescopes,

Chandra - an X-ray telescope - and

Spitzer - an infrared telescope - will also take a look.

It’s good to do this, Battam said, just to confirm that ISON is

indeed gone.

Though ISON may be gone, Battams pointed out that there’s still a

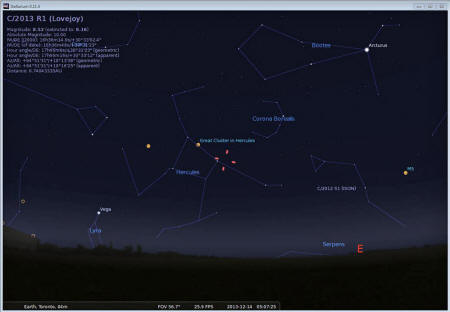

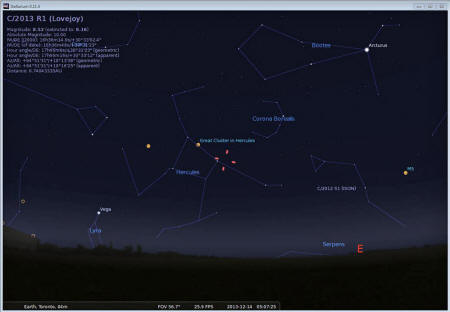

comet gracing our skies, Comet Lovejoy, that people can enjoy.

Comet ISON may be gone,

but Comet Lovejoy (C/2013 R1) is still

grazing the pre-dawn sky.

(Courtesy of Bill Longo)

The NRL has received many calls from people who bought telescopes in

the hope of catching ISON.

Now that it’s gone, they wonder if

there’s anything else to see.

“The sky is full of wonders. And the next bright comet is just

around the corner,” Battams said.

Where to find Comet Lovejoy

around 5 a.m. from a latitude of 43

degrees.

(Stellarium)

Next year will be chock-full of even more exciting comets.

There

will be

Comet C/2013 A1 (Siding Spring), which will pass incredibly

close to Mars at about 110,000 km above the planet’s surface (there

had been talk about it colliding with Mars, but calculations have

shown that this will not happen).

There is also the European Space

Agency’s

Rosetta mission which will release a lander on the

comet 67

P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

“And,” Battams said, “Who knows what will turn up in the meantime.”

Battams’s busy schedule is just settling down. He’s spent months

observing and analyzing ISON.

So, when asked what the next thing he’s excited about, Battams

laughed and said,

“A rest.”

Fire vs. Ice

The Science of ISON at Perihelion

December 10, 2013

from

NASA Website

After several days of continued observations, scientists continue to

work

to determine and understand the fate of Comet ISON:

There's no

doubt that the comet shrank in size considerably

as it rounded the

sun and there's no doubt that

something made it out on the other

side to shoot back into space.

Image Credit:

ESA/NASA/SOHO

After a year of observations, scientists waited with bated breath on

Nov. 28, 2013, as Comet ISON made its closest approach to the sun,

known as perihelion.

Would the comet disintegrate in the fierce heat

and gravity of the sun? Or survive intact to appear as a bright

comet in the pre-dawn sky?

Some remnant of ISON did indeed make it around the sun, but it

quickly dimmed and fizzled as seen with NASA's solar observatories.

This does not mean scientists were disappointed, however.

A

worldwide collaboration ensured that observatories around the globe

and in space, as well as keen amateur astronomers, gathered one of

the largest sets of comet observations of all time, which will

provide fodder for study for years to come.

On Dec. 10, 2013, researchers presented science results from the

comet's last days at the 2013 Fall American Geophysical Union

meeting in San Francisco, Calif.

They described how this unique

comet lost mass in advance of reaching perihelion and most likely

broke up during its closest approach, as well, as summarized what

this means for determining what the comet was made of.

"The comet's story begins with the very formation of the solar

system," said Karl Battams, an astrophysicist at the Naval Research

Lab in Washington, D.C.

"The dirty snowball that we came to call

Comet ISON was created at the same time as the planets."

ISON circled the solar system in the Oort cloud, more than 4.5

trillion miles away from the sun.

At some point a few million years

ago, something occurred – perhaps the passage of a nearby star – to

knock ISON out of its orbit and send it hurtling along a path for

its first trip into the inner solar system.

The comet was first spotted 585 million miles away in September 2012

by two Russian astronomers: Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok. The

comet was named after the project that discovered it, the

International Scientific Optical Network, or ISON, and given an

official designation of C/2012 S1 (ISON).

When comet scientists

mapped out Comet ISON's orbit they learned that the comet would

swing within 1.1 million miles of the sun's surface, making it

what's known as a sungrazing comet, providing opportunities to study

this pristine bit of the early solar system as it lost material

while approaching the higher temperatures of the sun.

With this

knowledge, an international campaign to observe the comet was born.

The number of space-based, ground-based, and amateur observations

was unprecedented, including 12 NASA space-based assets observing

Comet ISON over the past year.

Near the beginning of October, 2013, two months before perihelion,

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Observer, or MRO, turned its HiRISE

instrument to view the comet during its closest approach to Mars in

October 2013.

"The size of ISON's nucleus could be a little over half a mile

across - at the most. Very likely it could have been as small as

several hundred yards," said Alfred McEwen, the principal

investigator for the HiRISE instrument at Arizona State University,

in Tucson.

In other words, Comet ISON might have been the length of five or six

football fields. This small size was near the borderline of how big

ISON needed to be to survive its trip around the sun.

During that trip around the sun, Geraint Jones, a comet scientist at

University College London's Mullard Space Science Laboratory in the

UK studied the comet's dust tails to better understand what happened

as it rounded the sun.

By fitting models of the dust tail to the

actual observations from NASA's Solar Terrestrial Observatory, or

STEREO, and the joint European Space Agency/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, or SOHO, Jones showed that very little

dust was produced after perihelion, which may suggest that the

comet's nucleus had already broken up by that time.

A white plus sign shows where the Comet should have appeared in this

SDO image.

This image from NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory

shows the sun, but no

Comet ISON was seen.

A white plus sign

shows where the Comet should have appeared.

Image Credit: NASA/SDO

While the comet was visible in STEREO and SOHO images going into

perihelion, it was not visible in the data from NASA's Solar

Dynamics Observatory, or SDO, or from ground based solar

observatories during its closest approach to the sun.

Dean Pesnell, project scientist

for SDO at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.,

explained why Comet ISON wasn't visible in SDO and what could be

learned from that:

SDO is tuned to see wavelengths of

light that would indicate the presence of oxygen, which is very

common in comets.

"The fact that ISON did not show

oxygen despite how close it came to the sun provides

information about how high was the evaporation temperature

of ISON's material," said Pesnell.

"This limits what it

could have been made of."

When Comet ISON was first spotted in

September 2012, it was relatively bright for a comet at such a great

distance from the sun.

Consequently, many people had high hopes

it would provide a beautiful light show visible in the night sky

throughout December 2013. That potential ended when Comet ISON

disrupted during perihelion.

However, the legacy of the comet will go

on for years as scientists analyze the tremendous data set collected

during ISON's journey.

|