|

by David Biello

From the October 2007 issue of

Scientific American Mind

from

ScientificAmerican Website

The doughnut-shaped machine swallows the

nun, who is outfitted in a plain T-shirt and loose hospital pants

rather than her usual brown habit and long veil. She wears earplugs

and rests her head on foam cushions to dampen the device’s roar, as

loud as a jet engine.

Supercooled giant magnets generate

intense fields around the nun’s head in a high-tech attempt to read

her mind as she communes with her deity.

Image:

Neural Correlates of

a Mystical Experience in Carmelite Nuns, by M. Beauregard and V.

Paquette,

in Neuroscience

Letters, Vol. 405, No. 3; 2006.

Reproduced with

permission of Elsevier

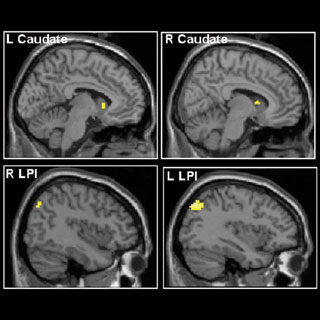

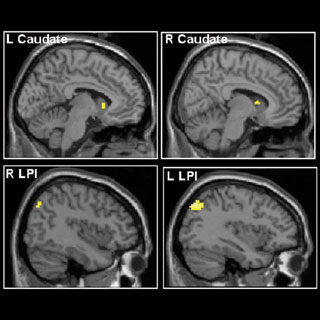

MYSTICAL HOT SPOTS:

In a 2006 study the

recall by nuns of communion with God

invigorated the

brain's caudate nucleus, insula, inferior parietal lobe (IPL)

and medial

orbitofrontal cortex (MOFC), among other brain regions.

The Carmelite nun and 14 of her Catholic

sisters have left their cloistered lives temporarily for this

claustrophobic blue tube that bears little resemblance to the wooden

prayer stall or sparse room where such mystical experiences usually

occur. Each of these nuns answered a call for volunteers “who have

had an experience of intense union with God ” and agreed to

participate in an experiment devised by neuroscientist Mario

Beauregard of the University of Montreal.

Using functional magnetic resonance

imaging (fMRI), Beauregard seeks to pinpoint the brain

areas that are active while the nuns recall the most powerful

religious epiphany of their lives, a time they experienced a

profound connection with the divine.

The question: Is there a God

spot in the brain?

The spiritual quest may be as old as humankind itself, but now there

is a new place to look: inside our heads. Using fMRI and other tools

of modern neuroscience, researchers are attempting to pin down what

happens in the brain when people experience mystical awakenings

during prayer and meditation or during spontaneous utterances

inspired by religious fervor.

Such efforts to reveal the neural correlates of the divine—a new

discipline with the warring titles “neurotheology” and “spiritual

neuroscience”—not only might reconcile religion and science but also

might help point to ways of eliciting pleasurable otherworldly

feelings in people who do not have them or who cannot summon them at

will. Because of the positive effect of such experiences on those

who have them, some researchers speculate that the ability to induce

them artificially could transform people’s lives by making them

happier, healthier and better able to concentrate.

Ultimately, however, neuroscientists

study this question because they want to better understand the

neural basis of a phenomenon that plays a central role in the lives

of so many.

“These experiences have existed

since the dawn of humanity. They have been reported across all

cultures,” Beauregard says. “It is as important to study the

neural basis of [religious] experience as it is to investigate

the neural basis of emotion, memory or language.”

Mystical

Misfirings

Scientists and scholars have long speculated that religious feeling

can be tied to a specific place in the brain. In 1892 textbooks on

mental illness noted a link between “religious emotionalism” and

epilepsy. Nearly a century later, in 1975, neurologist Norman Geschwind of the

Boston Veterans Administration Hospital first

clinically described a form of epilepsy in which seizures originate

as electrical misfirings within the temporal lobes, large sections

of the brain that sit over the ears.

Epileptics who have this form of the

disorder often report intense religious experiences, leading

Geschwind and others, such as neuropsychiatrist David Bear of

Vanderbilt University, to speculate that localized electrical storms

in the brain’s temporal lobe might sometimes underlie an obsession

with religious or moral issues.

Exploring this hypothesis, neuroscientist Vilayanur S.

Ramachandran of the University of California, San Diego, asked

several of his patients who have temporal lobe epilepsy to listen to

a mixture of religious, sexual and neutral words while he tested the

intensity of their emotional reactions using a measure of arousal

called the galvanic skin response, a fluctuation in the electrical

resistance of the skin.

In 1998 he reported in his book

Phantoms in the Brain, co-authored

with journalist Sandra Blakeslee, that the religious words,

such as “God,” elicited an unusually large emotional response in

these patients, indicating that people with temporal lobe epilepsy

may indeed have a greater propensity toward religious feeling.

The key, Ramachandran speculates, may be the limbic system, which

comprises interior regions of the brain that govern emotion and

emotional memory, such as the amygdala and hypothalamus. By

strengthening the connection between the temporal lobe and these

emotional centers, epileptic electrical activity may spark religious

feeling.

To seal the case for the temporal lobe’s involvement, Michael

Persinger of Laurentian University in Ontario sought to

artificially re-create religious feelings by electrically

stimulating that large subdivision of the brain. So Persinger

created the “God helmet,” which generates weak electromagnetic

fields and focuses them on particular regions of the brain’s

surface.

In a series of studies conducted over the past several decades,

Persinger and his team have trained their device on the temporal

lobes of hundreds of people. In doing so, the researchers induced in

most of them the experience of a sensed presence—a feeling that

someone (or a spirit) is in the room when no one, in fact, is—or of

a profound state of cosmic bliss that reveals a universal truth.

During the three-minute bursts of stimulation, the affected subjects

translated this perception of the divine into their own cultural and

religious language — terming it God, Buddha, a benevolent presence or

the wonder of the universe.

Persinger thus argues that religious experience and belief in God

are merely the results of electrical anomalies in the human brain.

He opines that the religious bents of even the most exalted

figures—for instance, Saint Paul, Moses, Muhammad and Buddha — stem

from such neural quirks. The popular notion that such experiences

are good, argues Persinger in his book

Neuropsychological Bases of God Beliefs

(1987), is an outgrowth of psychological conditioning in which

religious rituals are paired with enjoyable experiences. Praying

before a meal, for example, links prayer with the pleasures of

eating.

God, he claims, is nothing more mystical

than that.

Expanded

Horizons

Although a 2005 attempt by Swedish scientists to replicate

Persinger’s God helmet findings failed, researchers are not yet

discounting the temporal lobe’s role in some types of religious

experience. After all, not all such experiences are the same. Some

arise from following a specific religious tradition, such as the

calm Catholics feel when saying the rosary.

Others bring a person into a perception

of contact with the divine. Yet a third category might be mystical

states that reveal fundamental truths opaque to normal

consciousness. Thus, it is possible that different religious

feelings arise from distinct locations in the brain. Individual

differences might also exist. In some people, the neural seat of

religious feeling may lie in the temporal lobe, whereas in others it

could reside elsewhere.

Indeed, University of Pennsylvania neuroscientist Andrew Newberg

and his late colleague, Eugene d’Aquili, have pointed to the

involvement of other brain regions in some people under certain

circumstances. Instead of artificially inducing religious

experience, Newberg and d’Aquili used brain imaging to peek at the

neural machinery at work during traditional religious practices. In

this case, the scientists studied Buddhist meditation, a set of

formalized rituals aimed at achieving defined spiritual states, such

as oneness with the universe.

When the Buddhist subjects reached their self-reported meditation

peak, a state in which they lose their sense of existence as

separate individuals, the researchers injected them with a

radioactive isotope that is carried by the blood to active brain

areas. The investigators then photographed the isotope’s

distribution with a special camera—a technique called

single-photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT).

The height of this meditative trance, as they described in a 2001

paper, was associated with both a large drop in activity in a

portion of the parietal lobe, which encompasses the upper back of

the brain, and an increase in activity in the right prefrontal

cortex, which resides behind the forehead. Because the affected part

of the parietal lobe normally aids with navigation and spatial

orientation, the neuroscientists surmise that its abnormal silence

during meditation underlies the perceived dissolution of physical

boundaries and the feeling of being at one with the universe.

The prefrontal cortex, on the other

hand, is charged with attention and planning, among other cognitive

duties, and its recruitment at the meditation peak may reflect the

fact that such contemplation often requires that a person focus

intensely on a thought or object.

Neuroscientist Richard J. Davidson of the University of

Wisconsin–Madison and his colleagues documented something similar in

2002, when they used fMRI to scan the brains of several hundred

meditating Buddhists from around the world. Functional MRI tracks

the flow of oxygenated blood by virtue of its magnetic properties,

which differ from those of oxygen-depleted blood. Because oxygenated

blood preferentially flows to where it is in high demand, fMRI

highlights the brain areas that are most active during—and thus

presumably most engaged in—a particular task.

Davidson’s team also found that the Buddhists’ meditations coincided

with activation in the left prefrontal cortex, again perhaps

reflecting the ability of expert practitioners to focus despite

distraction. The most experienced volunteers showed lower levels of

activation than did those with less training, conceivably because

practice makes the task easier. This theory jibes with reports from

veterans of Buddhist meditation who claim to have reached a state of

“effortless concentration,” Davidson says.

What is more, Newberg and d’Aquili obtained concordant results in

2003, when they imaged the brains of Franciscan nuns as they prayed.

In this case, the pattern was associated with a different spiritual

phenomenon: a sense of closeness and mingling with God, as was

similarly described by Beauregard’s nuns.

“The more we study and compare the

neurological underpinnings of different religious practices, the

better we will understand these experiences,” Newberg says.

“We would like to [extend our work

by] recruiting individuals who engage in Islamic and Jewish

prayer as well as revisiting other Buddhist and Christian

practices.”

Newberg and his colleagues discovered

yet another activity pattern when they scanned the brains of five

women while they were speaking in tongues—a spontaneous expression

of religious fervor in which people babble in an incomprehensible

language. The researchers announced in 2006 that the activity in

their subjects’ frontal lobes—the entire front section of the

brain—declined relative to that of five religious people who were

simply singing gospel.

Because the frontal lobes are broadly

used for self-control, the research team concluded that the

decrement in activity there enabled the loss of control necessary

for such garrulous outbursts.

Spiritual

Networking

Although release of frontal lobe control may be involved in the

mystical experience, Beauregard believes such profound states also

call on a wide range of other brain functions. To determine exactly

what might underlie such phenomena, the Quebecois neuroscientist and

his colleagues used fMRI to study the brains of 15 nuns during three

different mental states. Two of the conditions—resting with closed

eyes and recollecting an intense social experience—were control

states against which they compared the third: reminiscence or

revival of a vivid experience with God.

As each nun switched between these states on a technician’s cue, the

MRI machine recorded cross sections of her brain every three

seconds, capturing the whole brain roughly every two minutes. Once

the neural activity was computed and recorded, the experimenters

compared the activation patterns in the two control states with

those in the religious state to elucidate the brain areas that

became more energized during the mystical experience.

(Although Beauregard had hoped the nuns

would experience a mystical union while in the scanner, the best

they could do, it turned out, was to conjure up an emotionally

powerful memory of union with God. “God can’t be summoned at will,”

explained Sister Diane, the prioress of the Carmelite convent in

Montreal.)

The researchers found six regions that were invigorated only during

the nuns’ recall of communion with God. The spiritual memory

was accompanied by, for example, increased activity in the caudate

nucleus, a small central brain region to which scientists have

ascribed a role in learning, memory and, recently, falling in love;

the neuroscientists surmise that its involvement may reflect the

nuns’ reported feeling of unconditional love. Another hot spot was

the insula, a prune-size chunk of tissue tucked within the brain’s

outermost layers that monitors body sensations and governs social

emotions. Neural sparks there could be related to the visceral

pleasurable feelings associated with connections to the divine.

And augmented activity in the inferior parietal lobe, with its role

in spatial awareness—paradoxically, the opposite of what Newberg and

Davidson witnessed—might mirror the nuns’ feeling of being absorbed

into something greater. Either too much or too little activity in

this region could, in theory, result in such a phenomenon, some

scientists surmise.

The remainder of the highlighted

regions, the researchers reported in the September 25, 2006, issue

of Neuroscience Letters, includes the medial orbitofrontal cortex,

which may weigh the pleasantness of an experience; the medial

prefrontal cortex, which may help govern conscious awareness of an

emotional state; and, finally, the middle of the temporal lobe.

The quantity and diversity of brain regions involved in the nuns’

religious experience point to the complexity of the phenomenon of

spirituality.

“There is no single God spot,

localized uniquely in the temporal lobe of the human brain,”

Beauregard concludes.

“These states are mediated by a

neural network that is well distributed throughout the brain.”

Brain scans alone cannot fully describe

a mystical state, however. Because fMRI depends on blood flow, which

takes place on the order of seconds, fMRI images do not capture

real-time changes in the firing of neurons, which occur within

milliseconds.

That is why Beauregard turned to a

faster technique called quantitative electroencephalography (EEG),

which measures the voltage from the summed responses of millions of

neurons and can track its fluctuation in real time. His team

outfitted the nuns with red bathing caps studded with electrodes

that pick up electric currents from neurons. These currents merge

and appear as brain waves of various frequencies that change as the

nuns again recall an intense experience with another person and a

deep connection with God.

Beauregard and his colleagues found that the most prevalent brain

waves are long, slow alpha waves such as those produced by sleep,

consistent with the nuns’ relaxed state. In work that has not yet

been published, the scientists also spotted even lower-frequency

waves in the prefrontal and parietal cortices and the temporal lobe

that are associated with meditation and trance.

“We see delta waves and theta waves

in the same brain regions as the fMRI,” Beauregard says.

Fool’s Errand?

The brain mediates every human experience from breathing to

contemplating the existence of God. And whereas activity in neural

networks is what gives rise to these experiences, neuro-imaging

cannot yet pinpoint such activity at the level of individual

neurons. Instead it provides far cruder anatomical information,

highlighting the broad swaths of brain tissue that appear to be

unusually dynamic or dormant.

But using such vague structural clues to

explain human feelings and behaviors may be a fool’s errand.

“You list a bunch of places in the

brain as if naming something lets you understand it,” opines

neuropsychologist Seth Horowitz of Brown University.

Vincent Paquette, who

collaborated with Beauregard on his experiments, goes further,

likening neuro-imaging to phrenology, the practice in which

Victorian-era scientists tried—and ultimately failed—to intuit clues

about brain function and character traits from irregularities in the

shape of the skull.

Spiritual neuroscience studies also face the profound challenge of

language. No two mystics describe their experiences in the same way,

and it is difficult to distinguish among the various types of

mystical experiences, be they spiritual or traditionally religious.

To add to the ambiguity, such feelings could also encompass awe of

the universe or of nature.

“If you are an atheist and you live

a certain kind of experience, you will relate it to the

magnificence of the universe. If you are a Christian, you will

associate it with God. Who knows? Perhaps they are the same,”

Beauregard muses.

Rather than attempting to define

religious experience to understand it, some say we should be boiling

it down to its essential components.

“When we talk about phenomena like a

mystical experience, we need to be a lot more specific about

what we are referring to as far as changes in attention, memory

and perception,” Davidson says.

“Our only hope is to specify what is

going on in each of those subsystems,” as has been done in

studies of cognition and emotion.

Other research problems abound. None of

the techniques, for example, can precisely delineate specific brain

regions. And it is virtually impossible to find a perfect so-called

reference task for the nuns to perform against which to compare the

religious experience they are trying to capture.

After all, what human experience is just

one detail different from the awe and love felt in the presence of God?

Making Peace

For the nuns, serenity does not come from a sense of God in their

brains but from an awareness of God with them in the world. It is

that peace and calm, that sense of union with all things, that

Beauregard wants to capture—and perhaps even replicate.

“If you know how to electrically or

neurochemically change functions in the brain,” he says, “then

you [might] in principle be able to help normal people, not

mystics, achieve spiritual states using a device that stimulates

the brain electromagnetically or using lights and sounds.”

Inducing truly mystical experiences

could have a variety of positive effects. Recent findings suggest,

for example, that meditation can improve people’s ability to pay

attention. Davidson and his colleagues asked 17 people who had

received three months of intensive training in meditation and 23

meditation novices to perform an attention task in which they had to

successively pick out two numbers embedded in a series of letters.

The novices did what most people do, the

investigators announced in June: they missed the second number

because they were still focusing on the first—a phenomenon called

attentional blink. In contrast, all the trained meditators

consistently picked out both numbers, indicating that practicing

meditation can improve focus.

Meditation may even delay certain signs of aging in the brain,

according to preliminary work by neuroscientist Sara Lazar of

Harvard University and her colleagues. A 2005 paper in

NeuroReport noted that 20 experienced meditators showed

increased thickness in certain brain regions relative to 15 subjects

who did not meditate. In particular, the prefrontal cortex and right

anterior insula were between four and eight thousandths of an inch

thicker in the meditators; the oldest of these subjects boasted the

greatest increase in thickness, the reverse of the usual process of

aging.

Newberg is now investigating whether meditation can

alleviate stress and sadness in cancer patients or expand the

cognitive capacities of people with early memory loss.

Artificially replicating meditative trances or other spiritual

states might be similarly beneficial to the mind, brain and body.

Beauregard and others argue, for example, that such mystical mimicry

might improve immune system function, stamp out depression or just

provide a more positive outlook on life.

The changes could be

lasting and even transformative.

“We could generate a healthy,

optimal brain template,” Paquette says. “If someone has a bad

brain, how can they get a good brain? It’s really [a potential

way to] rewire our brain.”

Religious faith also has inherent

worldly rewards, of course. It brings contentment, and charitable

works motivated by such faith bring others happiness.

To be sure, people may differ in their proclivity to spiritual

awakening. After all, not everyone finds God with the God

helmet.

Thus, scientists may need to retrofit the technique to the patient.

And it is possible that some people’s brains will simply resist

succumbing to the divine.

Moreover, no matter what neural correlates scientists may find, the

results cannot prove or disprove the existence of God. Although

atheists might argue that finding spirituality in the brain implies

that religion is nothing more than divine delusion, the nuns were

thrilled by their brain scans for precisely the opposite reason:

they seemed to provide confirmation of God’s interactions with them.

After all, finding a cerebral source for

spiritual experiences could serve equally well to identify the

medium through which God reaches out to humanity. Thus, the nuns’

forays into the tubular brain scanner did not undermine their faith.

On the contrary, the science gave them

an even greater reason to believe.

|