|

January 19, 2007 from Time Website

Neuroscientist Alvaro Pascual-Leone

instructed the members of one group to play as fluidly as they

could, trying to keep to the metronome's 60 beats per minute. Every

day for five days, the volunteers practiced for two hours. Then they

took a test.

The so-called transcranial-magnetic-stimulation (TMS) test allows scientists to infer the function of neurons just beneath the coil.

In the piano players, the TMS mapped how

much of the motor cortex controlled the finger movements needed for

the piano exercise. What the scientists found was that after a week

of practice, the stretch of motor cortex devoted to these finger

movements took over surrounding areas like dandelions on a suburban

lawn.

But Pascual-Leone did not stop there. He extended the experiment by having another group of volunteers merely think about practicing the piano exercise. They played the simple piece of music in their head, holding their hands still while imagining how they would move their fingers.

Then they too sat beneath the TMS coil.

For what the TMS revealed was that the region of motor cortex that controls the piano-playing fingers also expanded in the brains of volunteers who imagined playing the music - just as it had in those who actually played it.

If his results hold for other forms of movement (and there is no reason to think they don't), then mentally practicing a golf swing or a forward pass or a swimming turn could lead to mastery with less physical practice.

Even more profound, the discovery showed

that mental training had the power to change the physical structure

of the brain.

Yes, it can create (and lose) synapses, the connections between neurons that encode memories and learning. And it can suffer injury and degeneration.

But this view held that if genes and development dictate that one cluster of neurons will process signals from the eye and another cluster will move the fingers of the right hand, then they'll do that and nothing else until the day you die.

There was good reason for lavishly

illustrated brain books to show the function, size and location of

the brain's structures in permanent ink.

For one thing, it lowered expectations about the value of rehabilitation for adults who had suffered brain damage from a stroke or about the possibility of fixing the pathological wiring that underlies psychiatric diseases.

And it

implied that other brain-based fixities, such as the happiness set

point that, according to a growing body of research, a person

returns to after the deepest tragedy or the greatest joy, are nearly

unalterable.

These aren't minor tweaks either.

Something as basic as the function of the visual or auditory cortex can change as a result of a person's experience of becoming deaf or blind at a young age. Even when the brain suffers a trauma late in life, it can rezone itself like a city in a frenzy of urban renewal.

If a stroke knocks out, say, the

neighborhood of motor cortex that moves the right arm, a new

technique called constraint-induced movement therapy can coax

next-door regions to take over the function of the damaged area. The

brain can be rewired.

When no transmissions arrive from the eyes in someone who has been blind from a young age, for instance, the visual cortex can learn to hear or feel or even support verbal memory.

When signals from the skin or muscles bombard the motor cortex or the somatosensory cortex (which processes touch), the brain expands the area that is wired to move, say, the fingers.

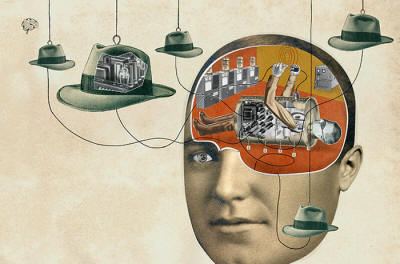

In this sense, the very structure of our brain - the relative size of different regions, the strength of connections between them, even their functions - reflects the lives we have led.

Like sand on a beach, the brain bears

the footprints of the decisions we have made, the skills we have

learned, the actions we have taken.

Soon after a car crash took Victor Quintero's left arm from just above the elbow, he told neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran of the University of California at San Diego that he could still feel the missing arm.

Ramachandran decided to investigate. He had Victor sit still with his eyes closed and lightly brushed the teenager's left cheek with a cotton swab.

Ramachandran stroked another spot on the cheek.

Ramachandran touched the skin between Victor's nose and mouth. His missing index finger was being brushed, Victor said. A spot just below Victor's left nostril caused the boy to feel a tingling on his left pinkie.

And when Victor felt an itch in his phantom hand, scratching his lower face relieved the itch. In people who have lost a limb, Ramachandran concluded, the brain reorganizes:

That's why touching Victor's face caused brain to

"feel" his missing hand.

Ramachandran's was the first report of a

living being knowingly experiencing the results of his brain

rewiring.

The brain can change as a result of the thoughts we think, as with Pascual-Leone's virtual piano players. This has important implications for health: something as seemingly insubstantial as a thought can affect the very stuff of the brain, altering neuronal connections in a way that can treat mental illness or, perhaps, lead to a greater capacity for empathy and compassion.

It may even dial

up the supposedly immovable happiness set point.

Schwartz had become intrigued with the therapeutic potential of

mindfulness meditation, the Buddhist practice of observing one's

inner experiences as if they were happening to someone else.

After 10 weeks of mindfulness-based therapy, 12 out of 18 patients improved significantly.

Before-and-after brain scans showed that activity in the orbital frontal cortex, the core of the OCD circuit, had fallen dramatically and in exactly the way that drugs effective against OCD affect the brain.

Schwartz called it "self-directed neuroplasticity," concluding that,

The same is true when cognitive techniques are used to treat depression.

Scientists at the University of Toronto had 14 depressed adults undergo CBT, which teaches patients to view their own thoughts differently - to see a failed date, for instance, not as proof that "I will never be loved" but as a minor thing that didn't work out.

Thirteen other patients received paroxetine (the generic form of the antidepressant Paxil). All experienced comparable improvement after treatment.

Then the scientists scanned the patients' brains.

But no. Depressed brains responded differently to the two kinds of treatment - and in a very interesting way.

CBT muted over-activity in the frontal cortex, the seat of reasoning, logic and higher thought as well as of endless rumination about that disastrous date. Paroxetine, by contrast, raised activity there.

On the other hand, CBT raised activity in the hippocampus of the limbic system, the brain's emotion center. Paroxetine lowered activity there.

As Toronto's Helen Mayberg explains,

As with

Schwartz's OCD patients, thinking had changed a pattern of activity

- in this case, a pattern associated with depression - in the brain.

To find out, neuroscientist Richard Davidson of the University of Wisconsin at Madison turned to Buddhist monks, the Olympic athletes of mental training.

Some monks have spent more than 10,000 hours of their lives in meditation. Earlier in Davidson's career, he had found that activity greater in the left prefrontal cortex than in the right correlates with a higher baseline level of contentment.

The relative left/right activity came to be seen as a marker for the happiness set point, since people tend to return to this level no matter whether they win the lottery or lose their spouse.

If mental training can alter activity characteristic of OCD and depression, might meditation or other forms of mental training, Davidson wondered, produce changes that underlie enduring happiness and other positive emotions?

With the help and encouragement of the Dalai Lama, Davidson recruited Buddhist monks to go to Madison and meditate inside his functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tube while he measured their brain activity during various mental states.

For comparison, he used undergraduates who had had no experience with meditation but got a crash course in the basic techniques.

During the generation of

pure compassion, a standard Buddhist meditation technique, brain

regions that keep track of what is self and what is other became

quieter, the fMRI showed, as if the subjects - experienced

meditators as well as novices - opened their minds and hearts to

others.

While the monks were generating feelings of compassion, activity in the left prefrontal swamped activity in the right prefrontal (associated with negative moods) to a degree never before seen from purely mental activity.

By contrast, the undergraduate controls showed no such differences between the left and right prefrontal cortex.

This

suggests, says Davidson, that the positive state is a skill that can

be trained.

But even as it offers new therapies for illnesses of the

mind, it promises something more fundamental: a new understanding of

what it means to be human.

|