|

by Paul Mason from TheGuardian Website

we are entering the post-capitalist era. At the heart of further change to come is information technology, new ways of working and the sharing economy. The old ways will take a long while to disappear,

but it's time to be utopian... The red flags and marching songs of Syriza during the Greek crisis, plus the expectation that the banks would be nationalized, revived briefly a 20th-century dream: the forced destruction of the market from above.

For much of the 20th century this was how the left conceived the first stage of an economy beyond capitalism.

The force would be applied by the

working class, either at the ballot box or on the barricades. The

lever would be the state. The opportunity would come through

frequent episodes of economic collapse.

Capitalism, it turns out, will not be abolished by forced-march techniques. It will be abolished by creating something more dynamic that exists, at first, almost unseen within the old system, but which will break through, reshaping the economy around new values and behaviors.

I call this

Postcapitalism.

Almost unnoticed, in the niches and hollows of the market system, whole swaths of economic life are beginning to move to a different rhythm.

Parallel currencies, time banks, cooperatives and

self-managed spaces have proliferated, barely noticed by the

economics profession, and often as a direct result of the shattering

of the old structures in the post-2008 crisis.

To mainstream economics such things seem barely to qualify as economic activity - but that's the point. They exist because they trade, however haltingly and inefficiently, in the currency of post-capitalism:

It

seems a meager and unofficial and even dangerous thing from which to

craft an entire alternative to a global system, but so did money and

credit in the age of Edward III.

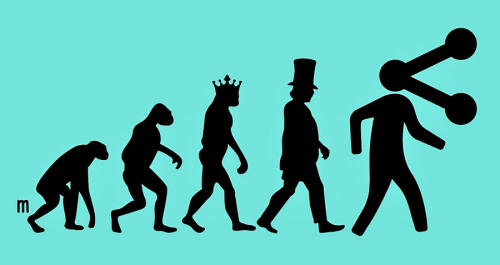

Sharing the fruits of our labour.

Illustration by Joe Magee

Buzzwords such as the "commons" and "peer-production" are thrown around, but few have

bothered to ask what this development means for capitalism itself.

So that, when we create the elements of the new system, we can say to ourselves, and to others:

Global growth became negative - on a scale where anything

below +3% is counted as a recession. It produced, in the west, a

depression phase longer than in 1929-33, and even now, amid a pallid

recovery, has left mainstream economists terrified about the

prospect of long-term stagnation. The aftershocks in Europe are

tearing the continent apart.

But they are

not working. In the worst-hit countries, the pension system has been

destroyed, the retirement age is being hiked to 70, and education is

being privatized so that graduates now face a lifetime of high debt.

Services are being dismantled and infrastructure projects put on

hold.

Real wages have fallen or

remained stagnant in Japan, the southern Eurozone, the US and UK.

The shadow banking system has been reassembled, and is now bigger

than it was in 2008. New rules demanding banks hold more reserves

have been watered down or delayed. Meanwhile, flushed with free

money, the 1% has got richer.

If we review the take-off periods studied by long-cycle theorists

- the 1850s in Europe, the 1900s and 1950s across the globe - it was

the strength of organized labour that forced entrepreneurs and

corporations to stop trying to revive outdated business models

through wage cuts, and to innovate their way to a new form of

capitalism.

Today there

is no pressure from the workforce, and the technology at the centre

of this innovation wave does not demand the creation of

higher-consumer spending, or the re‑employment of the old workforce

in new jobs. Information is a machine for grinding the price of

things lower and slashing the work time needed to support life on

the planet.

As a result, large parts of the business class have become

neo-luddites. Faced with the possibility of creating gene-sequencing

labs, they instead start coffee shops, nail bars and contract

cleaning firms: the banking system, the planning system and late

neoliberal culture reward above all the creator of low-value,

long-hours jobs.

Consider an airliner: a computer

flies it; it has been designed, stress-tested and "virtually

manufactured" millions of times; it is firing back real-time

information to its manufacturers. On board are people squinting at

screens connected, in some lucky countries, to the internet.

On a packed business

flight, when everyone's peering at Excel or Powerpoint, the

passenger cabin is best understood as an information factory.

Is it utopian to believe we're on the verge of an evolution beyond capitalism?

Illustration by Joe Magee

You won't find an answer in the accounts: intellectual property is valued in modern accounting standards by guesswork. A study for the SAS Institute in 2013 found that, in order to put a value on data, neither the cost of gathering it, nor the market value or the future income from it could be adequately calculated.

Only through a form of accounting that

included non-economic benefits, and risks, could companies actually

explain to their shareholders what their data was really worth.

Something is broken in the logic we use to value the most important

thing in the modern world.

But it is a value measured as usefulness, not exchange or asset value. In the 1990s economists and technologists began to have the same thought at once: that this new role for information was creating a new, "third" kind of capitalism - as different from industrial capitalism as industrial capitalism was to the merchant and slave capitalism of the 17th and 18th centuries.

But they have struggled to describe the dynamics of the new "cognitive" capitalism.

And for

a reason. Its dynamics are profoundly non-capitalist.

In 1962, Kenneth Arrow, the guru of mainstream economics, said that in a free market economy the purpose of inventing things is to create intellectual property rights.

He noted:

You can observe the truth of this in every e-business model ever constructed:

If we restate Arrow's principle in reverse, its revolutionary implications are obvious:

The

business models of all our modern digital giants are designed to

prevent the abundance of information.

Therefore, if the normal price mechanism of capitalism

prevails over time, its price will fall towards zero, too.

But it was actually imagined

by one 19th-century economist in the era of the telegraph and the

steam engine. His name? Karl Marx.

When they finally get to see what Marx is writing on this night, the left intellectuals of the 1960s will admit that it,

It is called "The Fragment on Machines".

The productive power of such machines as the automated cotton-spinning machine, the telegraph and the steam locomotive did not depend on the amount of labour it took to produce them but on the state of social knowledge.

Organization and

knowledge, in other words, made a bigger contribution to productive

power than the work of making and running the machines.

It

suggests that, once knowledge becomes a productive force in its own

right, outweighing the actual labour spent creating a machine, the

big question becomes not one of "wages versus profits" but

who

controls what Marx called the "power of knowledge".

In a final late-night thought experiment Marx imagined the end point

of this trajectory: the creation of an "ideal machine", which lasts

forever and costs nothing. A machine that could be built for nothing

would, he said, add no value at all to the production process and

rapidly, over several accounting periods, reduce the price, profit

and labour costs of everything else it touched.

We are surrounded by machines that cost

nothing and could, if we wanted them to, last forever.

In short, he had imagined something close to the

information economy in which we live. And, he wrote, its existence

would "blow capitalism sky high".

He wrote

its existence would blow capitalism sky high...

With the terrain changed, the old path beyond capitalism imagined by the left of the 20th century is lost. But a different path has opened up.

Collaborative production, using network technology to produce goods and services that only work when they are free, or shared, defines the route beyond the market system. It will need the state to create the framework - just as it created the framework for factory labour, sound currencies and free trade in the early 19th century.

The post-capitalist sector is likely

to coexist with the market sector for decades, but major change is

happening.

In

fact, once people understand the logic of the post-capitalist

transition, such ideas will no longer be the property of the left - but of a much wider movement, for which we will need new labels.

More than 200 years ago, the radical journalist John Thelwall warned the men who built the English factories that they had created a new and dangerous form of democracy:

Today the whole of society is a factory...

We all participate in the creation and recreation of the brands, norms and institutions that surround us. At the same time the communication grids vital for everyday work and profit are buzzing with shared knowledge and discontent.

Today it is the network - like the workshop 200 years ago - that they "cannot silence or disperse".

how modern political movements

straddle urban space

and cyberspace

And they can store and monitor every kilobyte of information we produce. But they cannot re-impose the hierarchical, propaganda-driven and ignorant society of 50 years ago, except - as in China, North Korea or Iran - by opting out of key parts of modern life.

It would be, as sociologist Manuel Castells put it, like trying to de-electrify a country.

There are, of course, the parallel and urgent tasks of decarbonizing the world and dealing with demographic and fiscal timebombs. But I'm concentrating on the economic transition triggered by information because, up to now, it has been sidelined.

Peer-to-peer has become pigeonholed as a

niche obsession for visionaries, while the "big boys" of leftwing

economics get on with critiquing austerity.

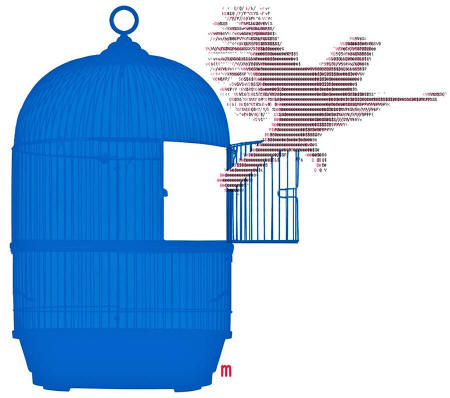

Information wants to be free.

Illustration by Joe Magee

Above all, post-capitalism as a concept is about new forms of human

behavior

that conventional economics would hardly recognize as relevant.

The first thing we have to recognize is:

Feudalism was an economic system structured by customs and laws about "obligation".

Capitalism was structured by something purely economic: the market. We can predict, from this, that post-capitalism - whose precondition is abundance - will not simply be a modified form of a complex market society.

But we can

only begin to grasp at a positive vision of what it will be like.

Perhaps there will not even be any playwrights:

Think of the difference between, say, Horatio in Hamlet and a character such as Daniel Doyce in Dickens's Little Dorrit.

Both carry around with them a characteristic obsession of their age - Horatio is obsessed with humanist philosophy; Doyce is obsessed with patenting his invention.

There can be no character like Doyce in Shakespeare; he would, at best, get a bit part as a working-class comic figure. Yet, by the time Dickens described Doyce, most of his readers knew somebody like him. Just as Shakespeare could not have imagined Doyce, so we too cannot imagine the kind of human beings society will produce once economics is no longer central to life.

But we can see their prefigurative forms in the lives of young

people all over the world breaking down 20th-century barriers around

sexuality, work, creativity and the self.

After that, there was a demographic shock: too few workers for the land, which raised their wages and made the old feudal obligation system impossible to enforce.

The labour shortage also forced

technological innovation. The new technologies that underpinned the

rise of merchant capitalism were the ones that stimulated commerce

(printing and accountancy), the creation of tradeable wealth

(mining, the compass and fast ships) and productivity (mathematics

and the scientific method).

In feudalism, many laws and customs were actually shaped around ignoring money; credit was, in high feudalism, seen as sinful.

So

when money and credit burst through the boundaries to create a

market system, it felt like a revolution. Then, what gave the new

system its energy was the discovery of a virtually unlimited source

of free wealth in the Americas.

At key moments, though tentatively at first, the state switched from

hindering the change to promoting it.

The equivalent of the printing press and the scientific method is information technology and its spillover into all other technologies, from genetics to healthcare to agriculture to the movies, where it is quickly reducing costs.

The modern equivalent of the long stagnation of late feudalism is the stalled take-off of the third industrial revolution, where instead of rapidly automating work out of existence, we are reduced to creating what David Graeber calls "bullshit jobs" on low pay.

And

many economies are stagnating...

The Internet, French economist Yann Moulier-Boutang says, is,

In fact, it is the

ship, the compass, the ocean and the gold.

They have not yet had the same impact as the Black Death - but as we

saw in New Orleans in 2005, it does not take the bubonic plague to

destroy social order and functional infrastructure in a financially

complex and impoverished society.

I call it Project Zero - because its aims are,

Most 20th-century leftists believed that they did not have the luxury of a managed transition:

As a result, once the possibility of a Soviet-style transition disappeared, the modern left became preoccupied simply with opposing things:

If I am right, the logical focus for supporters of post-capitalism is,

We have to learn what's urgent, and what's important, and

that sometimes they do not coincide.

The power of imagination will become critical.

In an information

society, no thought, debate or dream is wasted - whether conceived

in a tent camp, prison cell or the table football space of a startup

company.

Different people can work on it in different places, at different speeds, with relative autonomy from each other.

If I could summon one thing into existence for free it would be a global institution that modelled capitalism correctly: an open source model of the whole economy; official, grey and black.

Every experiment run through it would enrich it; it would be open

source and with as many datapoints as the most complex climate

models.

Everything comes down to the struggle between the network and the hierarchy:

We live in a world in which gay men and women can marry, and in which contraception has, within the space of 50 years, made the average working-class woman freer than the craziest libertine of the Bloomsbury era.

Why do we, then, find it so hard to imagine economic freedom? It is the elites - cut off in their dark-limo world - whose project looks as forlorn as that of the millennial sects of the 19th century.

The democracy of riot squads, corrupt politicians,

magnate-controlled newspapers and the surveillance state looks as phoney and fragile as East Germany did 30 years ago.

But why should we not form a picture of the ideal life,

built out of abundant information, non-hierarchical work and the

dissociation of work from wages?

Watching these emerge, from the

pro-Grexit

left factions in Syriza to the Front National and the isolationism

of the American right has been like watching the nightmares we had

during the Lehman Brothers crisis come true.

And we need to get on with it...

|