|

from Cymatics Website

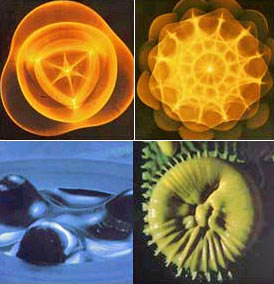

When he drew a violin bow around the edge of a plate covered with fine sand, the sand formed various geometric patterns, as shown below.

Another pioneer in this arena was Dr. Hans Jenny.

A Swiss medical doctor and a scientist, Dr. Jenny

realized the importance of vibration and sound and set out to study

them from a unique angle. His fascinating experiments into the study

of wave phenomena, which he called cymatics (from the Greek kyma,

meaning “wave”), provide nothing less than pictures of how sound

influences matter.

For many, these experiments show that sound can indeed alter form, that different frequencies produce different results, and that sound actually creates and maintains form.

The photographs below are taken from Dr. Jenny's work in cymatics. Used with permission from the two-volume edition of Cymatics: A Study of Wave Phenomena MACROmedia, 219 Grant Road, Newmarket, NH 03857.

Although best known for his stunning cymatic images, Dr. Jenny was also an artist and musician as well as a philosopher, historian and physical scientist. Perhaps most important, he was a serious student of nature’s ways with keen powers of observation.

Whether it was the cycle of the seasons, a bird’s feathers, a rain drop, the formation of weather patterns, mountains or ocean waves—or even poetry, the periodic table, music or social systems—Dr. Jenny saw an underlying, unifying theme: wave patterns, produced by vibration.

For him, everything reflected inherent patterns of vibration involving number, proportion and symmetry—what he called the “harmonic principle.”

Dr. Jenny encouraged continuing research into the wave phenomenon. The purpose of such studies, he explained, was to “hear” the systems of Nature.

Our Cells Respond to Sound

If sound can change substances, can it alter our interior landscape? Since patterns of vibration are ubiquitous in nature, what role do they play in creating and sustaining the cells of our own bodies? How do the vibrational patterns of a diseased body differ from the patterns the body emanates when it is healthy? And can we turn the unhealthy vibrations into healthy ones?

While Dr. Jenny did not focus on the

healing possibilities of sound and vibration, his work inspired many

whose destiny it was to do just that.

He then froze the water to make crystals and compared the crystalline structure of different samples. With each musical piece, the water sample formed different and beautifully geometric crystals.

When he played heavy

metal music, the water crystal’s basic hexagonal structure broke

into pieces.

Smaller groups of people have

repeated this experiment at other lakes around the world with

similar results, which Emoto has published in volume two of his

Messages from Water.

Notes

|