by Michael John Finley

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

May 2002 (revised Dec 2002)

from TheRealMayaProphecies Website

The Maya Venus

According to the Manuscript of Serna, a missionary report from central Mexico, the natives "adored and made more sacrifices" to Venus than any other "celestial or terrestrial creatures" apart from the sun. The Manuscript also tells us that:

The reason why this star was held in such esteem by the lords and people, and the reason why they counted their days by this star and yielded reverence and offered sacrifices to it, was because these deluded natives thought or believed that when one of their principal gods, named Topilzin or Quetzalcoatl, died and left this world, he transformed himself into that resplendent star.(1)

The Maya equivalent of Quetzalcoatl was Kukulkan. Both the Nahautl and Yucatec names translate as "quetzel bird-snake" or "plumed serpent". Kukulkan was a post-Classical deity, perhaps introduced to the Maya by the Toltecs, who were influential at Chichen Itza and other centres in the northern Yucatan.

Bishop Landa, writing in 1566 reported that:

[With] the Itzas who settled Chichen Itza there ruled a great lord named Cuculcan, as an evidence of which the principal building [pyramid] is called Cuculcan. They said he came from the West, but are not agreed as to whether he came before or after the Itzas, or with them. . . and that after his return he was regarded in Mexico as one of their gods, and called Cezalcohuati [Quetzalcoatl]. In the Yucatan also he was reverenced as a god, because of his great services to the state, as appeared in the order which he established in the Yucatan after the death of the chiefs, to settle the discord caused in the land . . . .(2)

Kukulkan

is

illustrated in the Venus pages of the Dresden Codex, which was

compiled

in the post-Classical period, probably after 1200 AD. But Venus was

important

in Maya myth and astronomy much earlier. The sun and Venus were adopted

as symbols of royal authority by the hierarchical states that took

shape

in the pre-Classical period.

Kukulkan

is

illustrated in the Venus pages of the Dresden Codex, which was

compiled

in the post-Classical period, probably after 1200 AD. But Venus was

important

in Maya myth and astronomy much earlier. The sun and Venus were adopted

as symbols of royal authority by the hierarchical states that took

shape

in the pre-Classical period.

A huge pair of jaguar masks decorated a temple facade at Cerros in about 50 BC. According to Schele and Freidel, the lower masks represent the sun at each horizon; the upper masks symbolize Venus as morning and evening star. In the Classical period (200-900 AD), Venus and the sun were identified with Hun Ahaw and Yax Balam, the "hero twins" who defeated the Lords of the Underworld, making creation of the present world possible.(3)

Their tale remained part of Maya mythology. It is recounted in detail in the post-conquest Quiche Popul Vuh, which names them Hunaphu and Xbalanque.

The mythological association between Venus and the sun has an astronomical foundation. Aveni suggests that it reflects Venus' "unique visual relationship to the sun". He notes that Venus "remains close to the sun, always becoming visible a few hours either before sunrise over the place the sun will come up, or after sunset over the place it went down".(4)

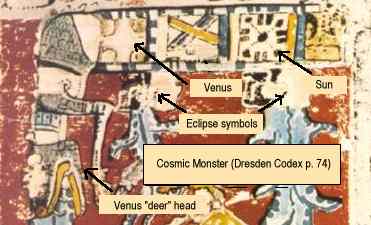

The Aztecs identified Venus as a dog who leads the sun, and the souls of kings, to the underworld. The two-headed Maya "cosmic monster", illustrated in both the Dresden Codex and Classical inscriptions, is marked by Venus symbols on one head, and solar symbols on the other. It too likely represents Venus leading the sun. The hero twins myth cycle is an account of the apparitions of Venus.

The heliacal rise of Venus, when it first rises in the morning sky in the east, marks the direction of sunrise and rebirth. Cosmical rise, when Venus rises at sunset in the west, is associated with evening and death. The period of invisibility between disappearance in the west at sunset and heliacal rise in the east marks Venus' sojourn in the underworld.(5)

According to the Manuscript of Serna, on the

day of the

heliacal rise of Venus, the natives "prepared a feast, warfare, and

sacrifices".

Perhaps because of its association with war, the heliacal rise of Venus

came to be regarded as a time when dire events could be expected.

According to the Manuscript of Serna, on the

day of the

heliacal rise of Venus, the natives "prepared a feast, warfare, and

sacrifices".

Perhaps because of its association with war, the heliacal rise of Venus

came to be regarded as a time when dire events could be expected.

The Anales de Cuauhtitlan (Codex Chimalpopca)(6),another post-conquest document from central Mexico, reports that at heliacal rise, Venus exercised a dangerous influence:

And so, when he [Venus] goes forth [rises], they know on what day sign he casts his light on certain people, venting his anger against them, shooting them with darts.

This was certainly part of Maya augury in the post-Classical period.

The Dresden Codex Venus pages show Venus deities armed with spears to pierce their victims. The primary function of the Venus table appears to have been to fix the dates of rituals associated with the apparitions of Venus and supply auguries for these dates.

The table is entered at a heliacal rise of Venus on the tzolk'in date 1 (hun) Ahaw, and tracks through 65 synodic periods of Venus (37960 days).

Familiarity with the Maya calendar is a prerequisite to a proper understanding of the Venus table. For an introduction to the calendar, see a brief Note on the Maya Calendar, where you will also find links to more detailed discussions of the calendar.

Star Wars

The timing of wars to coincide with the rise of Venus was adopted in the Maya area in the Classical period, and is associated with "Tlaloc war cult", which seems to have originated at Teotihaucan in Central Mexico. Tlaloc is the Aztec name of the central Mexican rain god, who, like his Maya counterpart Chac, has Venus associations.

Although the earliest representation of the Tlaloc warrior costume in the Mayan area (memorializing the conquest of Uaxactun by Tikal on 8.17.1.4.12 11, 16 January 378 AD) has has no astronomical significance, most inscriptions illustrating the Tlaloc costume do.

The astonishing murals at Bonampak illustrate a victory on 9.18.1.15.15 (16 August 792 AD), within a day or two of the heliacal rise of Venus. Schele and Freidel have shown that most wars recorded on classical stelae are dated to the heliacal rise of Venus, other apparitions of Venus, or to the stationary points of Jupiter and Saturn.

The most frequent "war glyph" in the inscriptions combines the Venus glyph and an emblem glyph, implying war at the place named by the emblem glyph (7)

.

.

The structure of the Venus

pages.

|

Six pages of the Dresden Codex are devoted to Venus. The left hand sides of pages 46-50 (according to the conventional page numbering) contain a table of dates of the rising and setting of Venus as morning and evening star. On each of these pages, the last station of Venus listed is heliacal rise. On the right hand side of each page, deities and auguries associated with heliacal rise are illustrated. The first Venus page (page 24) provides long count dates for entry into the table, a table of multiples, and what appears to be instructions for correcting the table for reuse at later dates. The Venus Pages On-line

Note on page numbers: Some time before Forstemann studied the Codex, it fell apart into two pieces that were improperly rejoined. Forstemann's edition divides the Venus pages. The first is numbered 24 by Forstemann, the others run from 46 to 50. These pages numbers were kept in most later editions, but the correct numbering is 24-29. |

.

.

The table of Venus apparitions

|

|

Ernst Forstemann discovered the Venus content of the table in 1901, when he noticed that the red numbers across the bottom of each of pages 46 to 50 are identical, and sum to 584(8). This is very close to the mean synodic period of Venus (583.92 days). The sequence of numbers making up the sum is 236, 90, 250, and 8.

These

divisions

in the synodic period are almost certainly intended to mark the four

principal

apparitions of Venus - visibility as morning star, invisibility at

superior

conjunction, visibility as evening star, and invisibility at inferior

conjunction.

The apparitions of Venus Venus' period of visibility as morning star begins with its heliacal rise--- the date on which it rises with the sun. It rises earlier, and thus rides higher in the sky at sunrise until it reaches maximum western elongation, about half way through its apparition as morning star.

Thereafter, it rises progressively closer to sunrise, finally rising after the sun so that it is lost from sight. At this time, Venus lies between the earth and sun. The midpoint of this period of invisibility is the moment of superior conjunction.

It re-emerges from the sun's glare when it rises at sunset (cosmic rise). It then rises progressively later as evening star until it reaches maximum eastern elongation. When it rises at sunset once again, it is lost behind the earth's shadow at inferior conjunction before re-appearing again as morning star.

The synodic period is the time required to complete a full set of apparitions, e.g. from heliacal rise to heliacal rise.

See Michielb's Maya Astronomy page for a description of Venus apparitions. |

Above the red numbers (separated from them by a block of text) are black numbers that record a running total from page 46 to page 50. A single pass through the five pages of the almanac tracks Venus over 5 synodic periods.

At the upper left of each page, there are 13 rows of tzolk'in dates. The tzolk'in is cycle of 260 days, each designated by one 20 day name glyphs and 13 numbers. Each row of tzolk'in dates corresponds to a pass through the table. Although many of the day signs have been obliterated, the structure of the table makes it possible to restore them. On the first page of the table, the first date in first row is 3 Kib.

This corresponds to superior conjunction of Venus, when Venus disappears after its apparition as morning star. The second date in the row is 2 Kimi, 90 days after superior conjunction, corresponding to cosmic rise as evening star. The next date is 5 Kib, 250 days later still, when Venus again disappeared at inferior conjunction. The last date in the row on this page is 13 K'an, 8 days later, marking heliacal rise.

The next page begins 236 days later, with superior conjunction again, on a day 2 Ahaw. After a complete pass through the table, it is re-entered again at the beginning, but on the second row of tzolk'in day signs.

Although the first station listed in the table is a superior conjunction date, the first total (recorded above it) is 236. This suggests that the table is intended to be entered 236 days before superior conjunction, at heliacal rise. The table thus appears to begin and end at heliacal rise. Since 3 Kib marks the first superior conjunction, the true entry date, found by counting back 236 days to heliacal rise, is 1 Ahaw.

Since 13 passes through the table are required to track through all 13 rows of tzolk'in dates, the table covers 5 x 13 = 65 Venus periods = 37960 days. The table is no doubt carried out this far to make it commensurate with the Calendar Round: 65 Venus periods = 146 tzolk'in = 104 haab = 2 calendar round cycles. Thus the table recovers the initial tzolk'in date on which table was entered after a complete cycle of 65 Venus periods.

The last date listed in the table is 1 Ahaw, the same tzolk'in date on which the table is entered. Lounsbury suggests that 1 Ahaw was chosen as the entry date because of the association of Venus with the hero twin Hun Ahaw.(9)

Note that between the 1 Ahaw heliacal rise dates at the beginning and end of the table, heliacal rise is recorded every 584 days. Because 584 is a whole multiple of 20 + 4, the day sign advances by four places at each heliacal rise through the table. Thus five day signs can correspond with heliacal rise, Ahaw, K'an, Lamat, Eb and Kib.

|

The 584 day period between heliacal rises is within one day of the average value of the true synodic period. As will be explained below, even greater accuracy was achieved by applying a correction on successive passes through the table.

But the times allotted to the apparitions of the planet between heliacal rises are much less accurate.

For example, Venus is morning star for an average of 263 days, rather than the 236 days allotted in the table.

In practice, the discrepancy is perhaps not as great as it may seem because of the difficulty in observing the planet when it rises or sets shortly before or after the sun, and because the actual synodic period varies from 581 to 587 days. In addition, the most important station, the time of heliacal rise, will be close to correct, occurring at 584 day intervals.

Nevertheless, the accuracy with which the scribes determined the mean synodic period proves they were competent Venusian observers, and leads to the conclusion that they deliberately altered the length of apparitions for ritualistic purposes. |

Gibbs suggests that the almanac distorts observation so that the auguries associated with the beginning of each apparition are consistent with established auguries for days in the tzol'kin.

He suggests that the almanac is contrived to bring the apparition dates as close to observation as possible while retaining the required links with the tzolk'in. Aveni has suggested that the dates of Venus apparitions may have been chosen in an effort to make the Venus cycle and the eclipse cycle commensurate.

He

noted

that the length of apparitions recorded in the Codex are

nearly

multiples of lunar months (236 days = 8 lunar months - 0.24

days; 90 days = 3 lunar months +1.41 days; and 250 days = 8.5 lunar

months

-1.25 days). (11)

Entering and using the table

Heliacal rise will fall on a day 1 Ahaw only rarely. If tzolk'in dates are ignored, the table could be used to track the apparitions of Venus if entered on any heliacal rise date. In practice, it is possible that the table was used in this way, as a computational aide for finding the number of days between rituals to be performed at stations in the planet's path through the heavens.

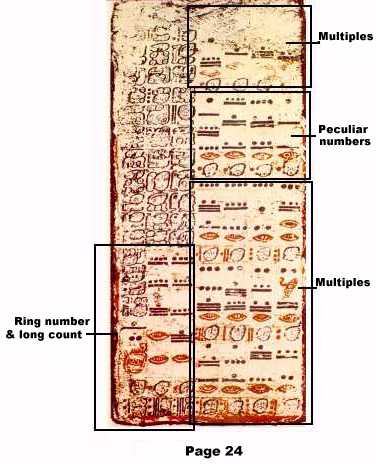

However, the mythological significance of rise on the day named for Hun Ahaw likely made entry into the table on such a day particularly significant. In fact, page 24 supplies long count dates that are days 1 Ahaw on which the table could have been entered.

The

entry dates are listed on the lower left hand side of page 24.

The

first column of the page contains the number 6.2.0. The k'in

coefficient

is circled in red and tied up with a bow knot.

The

entry dates are listed on the lower left hand side of page 24.

The

first column of the page contains the number 6.2.0. The k'in

coefficient

is circled in red and tied up with a bow knot.

This indicates what has been called a "ring number", which appears to be used to count back to a date prior to creation. The calendar round date of creation, 4 Ahaw 8 K'umku, is written below the ring number.

The number in the second column is 9.9.16.0.0. Below it, 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeb is written, but this is not the correct tzolk'in date if this is an ordinary long count number. It is, instead, what Thompson called a "long reckoning", counted forward from the date reached by the ring number.(12)

Transformed into a standard long count, it is 9.9.9.16.0 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeb. The number in the next column is also 9.9.9.16.0. This date is likely intended to be an entry into the table.

9.9.9.16.0 corresponds to 9 Feb 623 AD (Gregorian) if the '85 version of the GMT correlation is adopted. This should be a heliacal rise date , but in fact at this time Venus was 13-16 days from heliacal rise.

Thus, 9.9.9.16.0 does not appear to be a practical entry date into the Venus table. However, it is six centuries before the Dresden Codex was compiled. It is likely a throw-back, calculated by subtracting multiples of the length of the Venus table from a later 1 Ahaw that was close to heliacal rise.

9.9.9.16.0 fails to mark an actual date of heliacal rise because of the error that accumulates when the table is re-cycled. It was probably included in the Venus pages because of ritual or augural significance.

Lounsbury has called 9.9.16.0, the long reckoning used to reach the entry date, the "super-number of the codex" because it is a multiple of so many cycles-- 5,256 tzolk'ins, 3,744 haabs, 2,320 Venus periods, 72 calendar Rounds. The date before creation reached by the ring number is also a day 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeb, and thus another throw-back entry date.(13)

This may have been regarded as the date when Venus first rose in the prelude to creation.

For a fuller discussion of ring numbers, see Gregory Reddick, Ring and Serpent Numbers in the Dresden Codex

If 9.9.9.16.0 is a calculated entry date, the practical base of the table must have been a later 1 Ahaw. Identification of a plausible date depends on the correlation constant used to match long count positions with the Gregorian calendar, and thus with modern calculations of heliacal rise dates.

Lounsbury notes that if the '85 constant is adopted, as exceptionally good match occurred on 10.5.6.4.0 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeb = 25 November 934 AD, which was within 0.1 day of heliacal rise.

Moreover, the 9.9.9.16.0 heliacal rise date recorded in the Codex is an exact multiple of 584 day Venus periods earlier than 10.5.6.4.0, suggesting that the Codex rise date was calculated from the rise date discovered by Lounsbury. He identifies 10.5.6.4.0 as a "unique event in historical time".

He believes it is both strong evidence for the '85 correlation constant, and the probable date on which the Venus table was inaugurated.(14)

Lounsbury's argument has been accepted as definitive by many Mayanists, but it has not escaped criticism. Dennis Tedlock notes that the birth of God GI', father of the hero twins, is recorded at Palenque 780 days (3 tzolkin cycles or 1 synodic period of Mars) before the date given in the Dresden as the first rising of Venus. This suggests that a Venus table with 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeba s base date must have been in use at Palenque two centuries before 10.5.6.4.0.

Although no 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeb date can be closely matched with heliacal rise if the '83 constant is employed, several 1 Ahaw dates are available. Both 10.15.4.2.0 1 Ahaw 18 Wo (11 December 1129 AD) and 11.0.3.1.0 1 Ahaw13Mak (20 June 1227 AD) are heliacal rise dates if the '83 constant is correct. 11.5.2.0.0 1 Ahaw 3 Xul (28 December 1324 AD) is one day after heliacal rise. Tedlock noted that 1 Ahaw 18 Wo, 1 Ahaw 18Mak,and 1 Ahaw 3 Xul are dates on which the table can be adjusted if the correction scheme described below is applied. He suggests that this is evidence of revision of the table on one of these dates.(15)

See also The Correlation Question.

See the on-line Catalog of Venus heliacal risings and setting in the Yucatan

Re-cycling the table

The Venus table tracks through 65 synodic periods in order to recover the initial calendar round entry date. Since the true period of Venus is 593.92 days, significant error accumulates in less than one complete cycle through the table. 65 true periods is 38,604.8 days, rather than the 38,610 days recorded by the table. Thus the predicted heliacal rise of Venus is about 5 days late when the last station in the table is reached.

At heliacal rise, Venus is hidden in the glare of the sun at the horizon. Thus Venus is usually not sighted until about 4 days after the instant of heliacal rise. Thus a leeway of several days about the predicted rise date was likely acceptable, but by the end of the table, the error may have been large enough to be objectionable.

If the table is re-entered after 65 passes for a second complete run, the error continues to grow, and would almost certainly have become unacceptable. The scribes were aware of this problem, and incorporated a correction scheme into the table. At least the basic essentials of the method was deduced by J.E. Teeple in 1930.(16)

Page 24 includes a table of multiples of 584, obviously useful for calculating Venus periods and re-cycling the table.

There are in addition what have been called "peculiar numbers" on page 24. These are "peculiar" because all but the first is close to, but not exactly, a multiple of 584 days. Each is also an integral multiple of the tzolk'in. Teeple found evidence of the correction scheme in these numbers. If a peculiar number is counted from the 1 Ahaw entry date, it will reach another day 1 Ahaw. Thus the table can be re-entered at the beginning after the peculiar number is reached.

Teeple showed that this procedure could be used to correct cumulative error.

Reading from right to left, the peculiar numbers are:

Reading from right to left, the peculiar numbers are:

1.5.5.0 1 Ahaw

4.12.8.0 1 Ahaw = 33,280 days = 16 Venus periods - 8 days

9.11.7.0 1 Ahaw = 68,900 days = 118 Venus periods - 12 days

1.5.14.4.0 1 Ahaw = 185,000 days = 317 Venus periods - 8 days

Other similar relations are implied. In particular Teeple noted 9.11.7.0 - 4.12.8.0 = 4.18.17.0 = 61 Venus periods - 4 days.

For example, during a second run through the complete table, the scribe might stop at the second peculiar number, 12 days before reaching the end of the 118th Venus period. This position, according to the table, is 12 days before a heliacal rise station, but is a day 1 Ahaw. Since almost 2 full runs through the table have been completed, the table is in error by about 10 days, and heliacal rise is actually only 2 days in the future.

If the scribe now resets the count to 1 Ahaw at the beginning of the table, the prediction is for heliacal rise, which is only 2 days in error rather than 10. The sequence of tzolk'in dates for successive apparitions is restored. (Note, however, the haab date is changed. The correction occurs on a day 1 Ahaw 13 Mak if the almanac was initially entered on 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeb).

Similarly, the derived number 4.18.17.0 can be used to make a correction on the first run through the table. The scribe would stop 4 days before the 61st period ends, on a day 1 Ahaw, and reset the count of the beginning of the table. This reduces the accumulated 5 day error to 1 day.

Teeple suggested that by judicious use of the corrections, off-setting under corrections with overcorrections, the table could be kept within the limits of observational error. Applying the 4.12.8.0 correction in the first run, then the 4.18.17.0 correction in the second and third runs, is particularly attractive. This amounts to a 3 day overcorrection followed by two 1 day under corrections, leaving a cumulative error after three passes through the table of only 1 day.

Teeple also noted that the days reached by the peculiar numbers, counting from 1 Ahaw 18 K'ayeb, are 1 Ahaw 18 Wo, 1 Ahaw 13 Mak, and 1 Ahaw 18 Wo respectively. The three-step correction formula set out above reaches a re-entry date of 1 Ahaw 3 Xul. These dates are significant. Beneath the tzolk'in dates in the almanac run three series of haab dates. The haab dates listed beneath the 1 Ahaw station at the end of the almanac are 18 K'ayeb, 13 Mak, and 3 Xul. Thus they record haab dates of re-entry dates reached by the correction program.

18 Wo, which follows 18 K'ayeb on page 24, appears to complete the list.

It is almost certain that the scribes used a correction scheme very similar to the one proposed by Teeple. It is possible to manipulate the correction factors to obtain even greater accuracy, but less likely that the scribes did so. Thompson showed that a pattern of one 8 day correction followed by four 4 day corrections would keep the almanac very close to actual heliacal rising times. Since the series of 5 runs is foreshortened by this correction program by 8 + 4(4) = 24 Venus periods, a correction of 24 days in 65(5) - 24 = 301 Venus periods results. This gives a mean value for the synodic period of 583.92, almost exactly the figure now accepted..(17)

Thompson's correction program must be regarded as speculative at best. Unlike Teeple's suggested corrections, there is no clear internal evidence in the table to support it. As Lounsbury has suggested, it is unlikely that the Maya achieved the high accuracy Thompson attributed to them. Thompson was able to divine the super correction only by working back from the accurate data provided by modern astronomy, which could hardly have been matched with the observational methods available to the scribes.

The Maya were probably content with making corrections that kept predictions close to the limits of observational error while recovering 1 Ahaw. (18)

.

Venus Deities

|

|

Although Kukulkan was the post-Classical god most closely associated with Venus, the Dresden Codex Venus pages display a complex array of gods. Three sets of deities seem to be involved: (1) Gods ruling each apparition.

These deities are named in the texts above each station in the Venus table, and the deity who rules when Venus is morning star is illustrated at the top right of each page. (2)

The gods who represent Venus' malign influence at heliacal rise. These deities are illustrated as warriors, armed with spears, in the middle right of each page. (3)

The victims of Venus at heliacal rise. These deities are illustrated at the lower right, often pierced with spears presumably thrown by the gods of heliacal rise. The warrior gods of heliacal rise and their victims are named in the glyphic texts above their illustrations.

Lords of heliacal rise The gods of heliacal rise and their victims are best understood, in part because of parallels between the Dresden Venus table and central Mexican sources.

In the Anales de Cuauhtitlan, Venus' victims on each heliacal rise date are specific:

Each page of the Dresden Codex Venus table ends with heliacal rise on one of the four tzolk'in day names on which heliacal rise can occur. Like the Annales, the Codex identifies specific victims according to the day name of heliacal rise.

The most important clues to the identity of the Venus Lords and their victims come from yet another central Mexican source, the Borgia Codex and related pre-conquest manuscripts of the "Borgia group".

Two pages of the Borgia Codex are devoted to heliacal rise auguries, and illustrate Venus deities spearing victims on heliacal rise dates. In 1904, Eduard Seler worked out parallels between the Dresden and Borgia Venus deities.(20)

His insights, with more recent additions and amendments by Eric Thompson,(21) David Kelley (22) and others, remain a key to understanding the imagery of the Dresden Venus table. |

|

The Venus Lord in each panel of the Borgia is distinctive. In the Vaticanus, another Borgia group codex, a single deity represents Venus. Seler and Kelley identified the Venus Lords in the Borgia as separate deities, but it is as likely that all of them are aspects of Thahuizcalpantecuhtli, the Mexican god of the morning star.(23)

Most Mesoamerican deities have multiple aspects or manifestations. According to the Anales de Cuauhtitlan, after the death of Quetzalcoatl he was reborn as Thahuizcalpantecuhtl.

The Venus Lords of heliacal rise in the Dresden Codex are illustrated as distinct entities. However, there is some evidence that the Maya believed that the planets are "spirit companions" (way) or souls of gods. A deity may have more than one way, and several deities may share an identity through a common way.

As Venus Lord, each deity becomes the Venus way, and thus a manifestation of the planet personified as a god.

The Venus Lords differ in character, representing the differing influence of the planet on each of the tzolk'in dates on which heliacal rise can occur, but all are also Venus itself. |

|

The Borgia Group Codices

The Borgia Codex and two similar, less complete codices, Vaticanus B and Cospi contain what appear to be Venus tables. The Borgia table (pages 53-54) consists of 5 panels, each associated with a day name in the Mexican calendar. The pattern of day names is similar to the heliacal rise dates in the Dresden, but the days are displaced by one. For example, Cipactli (Crocidile) is a heliacal rise day.

This corresponds to Imix in the Maya calendar, which is the day after Ahaw,a heliacal rise day in the Dresden. The Borgia group lacks the mathematical sophistication of the Dresden Venus table, but the illustrations are more explicit. Anthony Aveni has recently shown that two other pages in the Borgia (27 and 28) may date other apparitions of Venus.

The Borgia was likely produced shortly before the conquest. It was originally attributed to the Mixtec, but is now thought to have been produced in Puebla or the Tehuacan Valley.

In any event, the style is "cosmopolitan", used throughout the Aztec realm.(24)

For an on-line introduction to the Borgia Group see John Pohl, Codex Borgia on line at the FAMSI website. The Borgia Venus pages can be viewed on-line. Aveni's article on Venus in the Borgia Codex in Natural History magazine, Other Stars than Ours, is also on-line.

|

The texts above the Venus warrior pictures all follow the same format. They begin with a verb well-known from the inscriptions, where it marks the accession of kings. It is followed by the logograph for lakin, "east".

Thus the text opens by recording, more or less literally, that "he acceded in the east", the direction of heliacal rise. The name of a god follows, together with the Venus glyph, literally chak ek, "great star". In the inscriptions, the names of rulers are usually followed by titles.

Thus chak ek should be read as a title, "Venus Lord".

The next glyph names the victim illustrated in the lower picture. It is followed by a phonetic collocation that reads u lu, "his sacrifice". Thus the victim is identified as the sacrifice of the Venus Lord. On page 46, for example, an Underworld deity known to Mayanists only as God L spears God K, K'awil, a deity associated with royal lineages. The value of the Borgia as an aide to interpreting the Dresden is clear in this case. The corresponding Borgia Venus Lord spears a throne on which a king sits.

Thus the victims of Venus are likely kings or nobles.

The remaining glyphs in the texts appear to be auguries for the heliacal rise date, or perhaps the Venus period that begins with heliacal rise. Unfortunately, the auguries remain rather obscure. .................................................................................................................... |

|

Page |

Venus Lord |

Victim |

Comment |

|

46 Day of heliacal rise K'an |

|

|

The illustration, like the name glyph, shows a black god. God L is one of several black gods, presumably Underworld deities. His rabbit-headed counterpart in the Borgia was identified by Seler as Mixcoatl, god of the hunt (sometimes portrayed as a rabbit). Mixcoatl is also a sky god, and has strong affinities with Thahuizcalpantecuhtli. God L has no Venus connection outside the Codex, but interestingly, a Classical Maya ceramic painting shows a rabbit stealing the paraphernalia of God L. The victim, K'awil, is associated with royal lineages. In the Borgia, a throne is speared. This suggests that kings are the target of Venus. |

|

47 Day of heliacal rise Lamat |

|

|

The name glyph of this god is Lahun chan, literally "10 sky". He is not known outside the Venus pages. The illustration of Lahun Chan shows him without a lower jaw, skeletal ribs, and a corn headdress. Seler pairs him with the Aztec Xipe Totec, the flayed god, associated with both human sacrifice and fertility. The victim is illustrated as a spotless cat, but the name glyph has the spots of a jaguar. Jaguars symbolize war. In the Borgia, a skeletal god spears a shield and spear symbol. Thus warriors may be the target of the Venus Lord. |

|

48 Day of heliacal rise Eb |

|

|

The half animal/half human Venus Lord was identified by Thompson as a jaguar, and by Kelley as a frog. His name glyph suggests an insect or caterpillar, and in fact the features of the illustrated warrior may well be insectoid. The victim is God E, the Corn God. In the Borgia, a rat-faced deity spears a corn deity, and worms eat corn cobs. The Venus Lord likely represents pests that attack the corn crop. |

|

49 Day of heliacal rise Kib |

|

|

The Venus Lord is illustrated with a bird on one ear flare, and a snake on the other (or issuing from his mouth). This is the deity on the Venus pages that can most readily be identified as Kukulkan. The victim is illustrated as a turtle headed deity with a jade necklace. The victim's name glyph includes the K'ank'in turtle head. Thompson equated this deity with "the turtle god of rain". Ethnographers report that turtles are protected in the Yucatan to avoid drought. In the Borgia, the Venus Lord, identified by Seler as Quetzalcoatl, spears a goddess, who Kelley identifies as Chalchihuitlicue, Jade Skirt, a water goddess. Drought is implied. |

|

50 Day of heliacal rise Ahaw |

|

|

The illustration shows a white god who appears to be blindfolded. Thompson suggested that this deity may correspond to the Mexican Tezcatlipoca- Itzlacoiliuhqui-Ixquimilli, a blindfolded god. There is no matching illustration in the Borgia. The victim is a youthful god dressed as a warrior. Warriors or youth may be the target of the Venus Lord. |

|

Lords of Venus as morning star Unlike the Venus Lords who attack victims at heliacal rise, the deities illustrated in the upper registers appear to be gods who rule throughout Venus' career as morning star.

They are seated on thrones, usually decorated with sky-bands. The texts above these pictures are damaged, and the identity of the ruling deity is not always clear. The deity enthroned on page 46 is an unidentified elderly god.

On page 47, Death God A is enthroned. On page 48, God N is portrayed. On page 49, a Moon Goddess is pictured. On Page 50, a white Death God occupies the throne, and God E, the Maize God, stands before him.

Lords of other apparitions While the illustrations and texts on the right hand side of each page concern only Venus as morning star (from heliacal rise to disappearance), the texts on the left hand side of each page identify the deities that rule during each apparition of the planet. . |

Recall that the numbers at the foot of the page are the "stations" marking apparitions of Venus from superior conjunction to heliacal rise as morning star. Each of the columns of text above these numbers corresponds to an apparition.

The upper part of each column, between the tzolk'in dates and the cumulative totals, names the deity who rules the apparition. The last on each page (corresponding to heliacal rise) is the Venus Lord of the Morning Star, the same deity enthroned at the top right. The texts follow a more of less standard format, usually consisting of the accession glyph, a direction glyph, a deity name, and the Venus glyph.

North is associated with superior conjunction, west with cosmic rise as evening star, south with inferior conjunction, and east with heliacal rise as morning star.

The same deities are named in the columns of text below the totals. Each of these columns of text consists of a deity name, a verb read as "was set up", the Venus glyph, and direction glyph. Thus the clause may report that a deity or his idol is set up at a cardinal point. The directions and deity names are those recorded above, but (with a few exceptions), advanced one place.

This suggests that at each apparition, a ritual

anticipating

the next was performed.

The Venus Table.

|

.......................Page 46 .................... |

..Page 47................................ |

..Page 48............................... |

|

S Conj |

CR |

I conj |

HR |

S Conj |

CR |

I conj |

HR |

S Conj |

CR |

I conj |

HR |

||||

|

Cycle 1 |

3Kib |

2Kimi |

5Kib |

13Kan |

2Ahaw |

1Ok |

4Ahaw |

12Lamat |

1Kan |

13Ix |

3Kan |

11Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 2 |

11Kib |

10Kimi |

13Kib |

8Kan |

10Ahaw |

9Ok |

12Ahaw |

7Lamat |

9Kan |

8Ix |

11Kan |

6Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 3 |

6Kib |

5Kimi |

8Kib |

3Kan |

5Ahaw |

4Ok |

7Ahaw |

2Lamat |

4Kan |

3Ix |

6Kan |

1Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 4 |

1Kib |

13Kimi |

3Kib |

11Kan |

13Ahaw |

12Ok |

2Ahaw |

10Lamat |

12Kan |

11Ix |

1Kan |

9Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 5 |

9Kib |

8Kimi |

11Kib |

6Kan |

8Ahaw |

7Ok |

10Ahaw |

5Lamat |

7Kan |

6Ix |

9Kan |

4Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 6 |

4Kib |

3Kimi |

6Kib |

1Kan |

3Ahaw |

2Ok |

5Ahaw |

13Lamat |

2Kan |

1Ix |

4Kan |

12Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 7 |

12Kib |

11Kimi |

1Kib |

9Kan |

11Ahaw |

10Ok |

13Ahaw |

8Lamat |

10Kan |

9Ix |

12Kan |

7Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 8 |

7Kib |

6Kimi |

9Kib |

4Kan |

6Ahaw |

5Ok |

8Ahaw |

3Lamat |

5Kan |

4Ix |

7Kan |

2Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 9 |

2Kib |

1Kimi |

4Kib |

12Kan |

1Ahaw |

13Ok |

3Ahaw |

11Lamat |

13Kan |

12Ix |

2Kan |

10Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 10 |

10Kib |

9Kimi |

12Kib |

7Kan |

9Ahaw |

8Ok |

11Ahaw |

6Lamat |

8Kan |

7Ix |

10Kan |

5Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 11 |

5Kib |

4Kimi |

7Kib |

2Kan |

4Ahaw |

3Ok |

6Ahaw |

1Lamat |

3Kan |

2Ix |

5Kan |

13Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 12 |

13Kib |

12Kimi |

2Kib |

10Kan |

12Ahaw |

11Ok |

1Ahaw |

9Lamat |

11Kan |

10Ix |

13Kan |

8Eb |

|||

|

Cycle 13 |

8Kib |

7Kimi |

10Kib |

5Kan |

7Ahaw |

6Ok |

9Ahaw |

4Lamat |

6Kan |

5Ix |

8Kan |

3Eb |

|||

|

MR |

4 Yaxkin |

14 Sak |

19 Sec |

7 Xul |

3Kumku |

8Sotz |

18 Pax |

6 Kayeb |

17 Yax |

7Muwan |

12 Chen |

0 Yax |

|||

|

236 |

326 |

576 |

584 |

820 |

910 |

1160 |

1168 |

1404 |

1494 |

1744 |

1752 |

||||

|

LR |

9 Sak |

19Muwan |

4 Yax |

12 Yax |

3 Sotz |

13Mol |

18 Wo |

6 Sip |

2Muwan |

7 Pop |

17 Mak |

5Kankin |

|||

|

236 |

90 |

250 |

8 |

236 |

90 |

250 |

8 |

236 |

90 |

250 |

8 |

||||

|

Page49.............................................................Page50...................................................................................................................... |

|||||||||||||||

|

S Conj |

CR |

I conj |

HR |

S Conj |

CR |

I conj |

HR |

||||||||

|

Cycle 1 |

13Lamat |

12Etznab |

2Lamat |

10Kib |

12Eb |

11Ik |

1Eb |

9Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 2 |

8Lamat |

7Etznab |

10Lamat |

5Kib |

7Eb |

6Ik |

9Eb |

4Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 3 |

3Lamat |

2Etznab |

5Lamat |

13Kib |

2Eb |

1Ik |

4Eb |

12Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 4 |

11Lamat |

10Etznab |

13Lamat |

8Kib |

10Eb |

9Ik |

12Eb |

7Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 5 |

6Lamat |

5Etznab |

8Lamat |

3Kib |

5Eb |

4Ik |

7Eb |

2Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 6 |

1Lamat |

13Etznab |

3Lamat |

11Kib |

13Eb |

12Ik |

2Eb |

10Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 7 |

9Lamat |

8Etznab |

11Lamat |

6Kib |

8Eb |

7Ik |

10Eb |

5Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 8 |

4Lamat |

3Etznab |

6Lamat |

1Kib |

3Eb |

2Ik |

5Eb |

13Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 9 |

12Lamat |

11Etznab |

1Lamat |

9Kib |

11Eb |

10Ik |

13Eb |

8Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 10 |

7Lamat |

6Etznab |

9Lamat |

4Kib |

6Eb |

5Ik |

8Eb |

3Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 11 |

2Lamat |

1Etznab |

4Lamat |

12Kib |

1Eb |

13Ik |

3Eb |

11Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 12 |

10Lamat |

9Etznab |

12Lamat |

7Kib |

9Eb |

8Ik |

11Eb |

6Ahaw |

|||||||

|

Cycle 13 |

5Lamat |

4Etznab |

7Lamat |

2Kib |

4Eb |

3Ik |

6Eb |

1Ahaw |

|||||||

|

MR |

11 Sip |

1 Mol |

6 Wo |

14 Wo |

10 Kankin |

0Wayeb |

5 Mak |

13 Mak |

|||||||

|

1988 |

2078 |

2328 |

2336 |

2572 |

2662 |

2912 |

2920 |

||||||||

|

LR |

16Yaxkin |

6 Keh |

11 Xul |

19 Xul |

15Kumku |

0 Sek |

10Kayeb |

18Kayeb |

|||||||

|

236 |

90 |

250 |

8 |

236 |

90 |

250 |

8 |

||||||||

Deities of the apparitions

|

Page 46 |

Page 47 |

Page 48 |

Page 49 |

Page 50 |

|||||||||||||||

|

Middle Register |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

I |

J |

K |

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

Q |

R |

S |

T |

|

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

|

ulum |

. |

. |

God A |

. |

God A' |

Muan |

God N'' |

God G |

Katun |

Night |

Moon |

God B |

God A |

God K |

God H |

God E |

God L |

Peccary |

. |

|

Lower Register |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

T |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

H |

I |

J |

K |

L |

M |

N |

O |

P |

Q |

R |

S |

|

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

East |

North |

West |

South |

Thompson labeled the twenty deities with the letters A-T. In the middle register texts, the gods appear in order from A to T. In the lower register texts, T is first , followed by A to S in order. Barthel identified many of the gods in 1952.(24)

Most of them are gods known from other contexts.

Thompson was certainly

wrong in speculating that they represent constellations.

References

Anthony F. Aveni. Skywatchers. Univ. of Texas, 2001 (revision of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico).

"The Real Venus-Kukulcan in Maya Inscriptions and Alignments". Sixth Palenque Round Table, 1986. eds. Robertson and Fields, U Okla, 1986

"The Moon and the Venus Table: An Example of Commensuration in the Maya Calendar", in Anthony F. Aveni, ed. The Sky in Mayan Literature. Oxford, 1992.

Barthel.Thomas S. "Der Morgensternkult in den Darstellungen der Dresdener Mayahandschrift". Ethnos 17, 1952.

Bricker, V.R. "A method for dating venus almanacs in the Borgia Codex," JHAS (Archaeoastronomy) No. 26 S21-44 (2001)

Closs, Michael P. "Venus in the Maya World: Glyphs, Gods and Associated Astronomical Phenomena", in Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque, . eds. Robertson and Jeffers, Herald Printers, 1979

"A Glyph for Venus as Evening Star", in Septima Mesa Redonda de Palenque, eds. Robertson and Jeffers, University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

Diaz, Gisele and Rodgers, Alan. The Codex Borgia. Dover Publications, 1993. (Introduction ny Bruce E. Byland).

Forstemann, Ernst. Commentar zur Mayahandschrift der koniglichen offentlichen Bibliothek zu Dresden. Dresden, 1901. Trans. as Commentary on the Maya Manuscript in the Royal Public Library at Dresden. Papers of the Peabody Museum Vol. 4, no. 2, 1906. (re-published as Commentary on the Dresden Codex by Aegean Park Press).

Gibbs, S. "Mesoamerican Calendars as Evidence of Astronomical Activity", in Anthony F. Aveni (ed.). Native American Astronomy. University of Texas, 1977.

Kelley, David. Deciphering the Maya Script. Univ. of Texas, 1976.

Friar Diego de Landa, Yucatan Before and After the Conquest (1566). Dover reprint of Gates' translation, 1978.

Floyd G. Lounsbury. "Maya Numeration, Computation, and Calendrical Astronomy", in C.C. Gillispie, Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978.

"A Derivation of the Mayan-to-Julian Calendar Correlation from the Dresden Codex Venus Chronology", in Anthony F. Aveni, ed. The Sky in Mayan Literature. Oxford, 1992.

Eduard Seler. Mexican Antiquities (translation of nine articles). Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 28, 1904.

J. de la Serna. Manual de Ministros de Indios. Collection de Documentos Ineditos para la Historia de Espana. Madrid, 1892.

Linda Schele and David Freidel. A Forest of Kings. William Morrow, 1990.

Linda Schele, David Freidel, and Joy Parker. Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path. William Morrow and Company, 1993

Karl A. Taube and Bonnie L. Bade. "An appearance of Xiuhtecuhtli in the Dresden Venus pages." Washington: Center for Maya Research, 1991. 1 v.:. bibl., ill.

Dennis Tedlock. Popol Vuh. Simon and Schuster, 1985. (Complete text on-line)

"Myth, Math, and the Problem of Correlation in Mayan Books", in Anthony F. Aveni, ed. The Sky in Mayan Literature. Oxford, 1992.

J. E. Teeple. Maya Astronomy. Carnagie Institution Publication 403, no. 2, 1930.

Thompson, J. Eric S. Maya Hieroglyphic Writing Introduction. Carnegie Institute Pub.589, 1950.

A Commentary on the Dresden Codex. American Philosophical Society, Memoir no. 93, 1972.

Carlos Villacorta and J.Antonio Villacorta, Codices Mayas, Guatemala, 1930. (The reproduction of the Dresden Codex has been seperately republished by Aegean Park Press).

P. F. Velasquez (ed. and trans.). Anales de Cuauhtitlan y leyenda de los soles. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, n.d.