by Michael John Finley

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

May 2002 (revised Dec 2002)

from TheRealMayaProphecies Website

by Michael John Finley

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

May 2002 (revised Dec 2002)

from TheRealMayaProphecies Website

"Mars Beast" (page 45b col. 1) |

In 1924, R. W. Willson suggested that pages 43-45 of the Dresden Codex contain a table tracking the motions of Mars.(1) Across the middle of the these pages runs an almanac that counts through 780 days, which is very close to the synodic period of the planet. Astronomical content is also suggested by the illustrations accompanying the almanac: Four images of a peculiar beast hang from a sky band, the symbol of the ecliptic in the Codex. This creature has come to be known as the "Mars beast". Willson's hypothesis was based on the same logic that led to discovery of the eclipse and Venus tables in the Codex: In all three cases, the subject matter was initially guessed because the numbers in the table approximate astronomical cycles. However, the putative Mars table was not as readily accepted as the eclipse and Venus tables.

|

The almanac is divided into ten 78 day intervals. As J. Eric Thompson noted, these divisions have no clear astronomical meaning. The total of 780 days is three 260 day tzolk'in cycles. Thompson believed that the "Mars table" was merely a long tzolk'in almanac with no astronomical significance.(4)

The Mars table hypothesis was revived in 1976 by David Kelley(5). In 1986, Victoria and Harvey Bricker pointed out that Mars undergoes retrograde motion (when it reverses its path along the ecliptic) for about 75 days in each synodic revolution.(6)

They suggested that the scribes who composed the table took 78 days, one-tenth of the synodic period, as an idealized value of the time Mars is retrograde. In addition, the Brickers, working with Anthony Aveni, have recently shown that the Codex likely contains a second Mars table (pages 69-74), which is concerned with the sidereal motion of the planet.(7)

The Mars table hypothesis is now widely accepted, though some students of the codices remain unconvinced. Bruce Love attempted to re-open the debate in 1995, suggesting that the table is an agricultural and weather almanac.(8)

His argument was countered in a reply by the Brickers in the same journal in 1997. (9)

The Maya Mars

Thompson thought it significant that Willson advanced his Mars table hypothesis "at a time when every Maya record was believed to have had an astronomical meaning." The implication was fair enough. The search for astronomical material in the codices that followed Forstemann's discovery of the Venus table led to some absurd theorizing.

Spinden was convinced that pages 43b-45b were concerned with Jupiter; Makemson thought they treated equinoxes and solstices. Another table containing multiples of 78 was related to Saturn by Spinden, and to Mars by Willson and Makemson.

Thompson also doubted that Mars attracted the scribes' attention because there was little evidence when he wrote that the Maya were interested in any planet other than Venus. While Venus figures importantly in Mesoamerican mythology, Mars is not known from post-conquest mythological sources. However, we now know that Mars is referred to, though obliquely, in inscriptions of the Classical period.

Perhaps the most remarkable example of the ritual use of planetary events is the record of the dedication ceremonies of the Group of the Cross at Palenque. The rituals fell within a four day period commencing 9.12.18.5.16 2 Kib 14 Mol , July 23 690 AD. At this time, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and the Moon were separated by intervals of less than 5 degrees.

According to Dutting and Aveni, "[On 23 July 690 AD all four planets were close together (a quadruple conjunction) in the same constellation, Scorpio, and they must have made quite a spectacle with bright red Antares shining but a few degrees south of the group as they straddled the high ridge that forms the southern horizon at Palenque.

The night before, the moon would have been just at the western end of the planetary lineup."(10)

The inscriptions of the Cross Group begin with an account of creation, the birth of first mother and first father, and of their sons, the gods of the Palenque triad. Schele and Freidel suggested that the alignment was interpreted as the re-uniting of First Mother (the moon) and her three sons.(11)

No Mesoamerican deity can be called "the Mars God", but it is likely that the planet was regarded as a manifestation or way ("spirit companion") of various deities. The inscriptions of the Cross Group refer to the planets in conjunction as spirit companions of the triad deities.

The primary identification of these gods is with Venus and the sun, but this would not have prevented them from manifesting as Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Left: "His way in conjunction, GIII" (Temple of the Sun O5-O6).

Familiarity

with the Maya calendar is a prerequisite to a proper understanding of

the

Mars table. For an introduction to the calendar, see a brief

Note

on the Maya Calendar, where you will also find links to more

detailed

discussions of the calendar.

Structure of the Mars Table

The Mars

almanac

runs across the middle registers of pages 43 to 45 (usually designated

43b-45b). The table proper begins on the right edge of page

44b,

where the Mars beast is illustrated for the first time. Below the

beast,

the number 19 is painted in black.

The Mars

almanac

runs across the middle registers of pages 43 to 45 (usually designated

43b-45b). The table proper begins on the right edge of page

44b,

where the Mars beast is illustrated for the first time. Below the

beast,

the number 19 is painted in black.

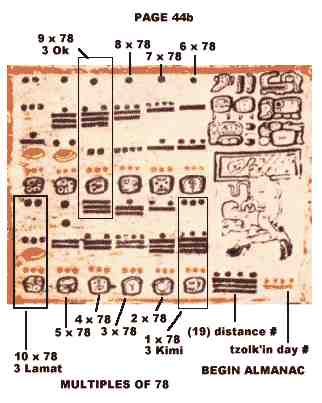

In tzolk'in almanacs in the codices, black numbers usually indicate the count of days between tzolk'in dates, the stations of the almanac marking auguries or rituals. There are three similar columns on page 45b.

The black numbers beneath the images of the beast on 45b are 19, 19, and 21. Thus a single pass through the stations of the almanac counts through 19 + 19 +19 + 21 = 78 days. For reasons which will be explained below, it appears that the almanac is entered on 3 Lamat. A count of 19 days forward reaches 9 Manik'.

The black distance number 19 below the first Mars beast is followed by red 9, which indicates the day number of the tzolk'in date reached by the first count. The count continues through 2 Kimi, 8 Chikchan, and 3 Kimi. This marks the end of the first pass.

If the table is then re-entered at the beginning, a count of 19 days reaches 9 Chikchan. Note that the day numbers are the same in the second and subsequent passes as in the first. The day names are different, which explains why the almanac records only day numbers.

Multiple passes through the almanac were clearly intended. Two rows of tzolk'in dates run across page 44b.

The date in the lower right corner of the rows is 3 Kimi. Above it is the number (in Maya notation) 3.18 = 78 days, indicating that 3 Kimi is reached at the end of the first pass. The next date in the row (reading toward the left) is 3 K'an. Above it is the number 7.16 = 2 x 78. This is the date reached at the end of the second pass.

The row of dates continues through higher multiples of 78, reaching 3 Etz'nab on the fifth pass. The pattern then continues on upper the row, from right to left, reaching 3 Ok on the ninth pass. The tenth multiple seems to be misplaced: It is 2.3.0 3 Lamat, listed at the left end of the lower row.

Thus a complete cycle of 10 passes through the table begins and ends on 3 Lamat.

The Mars Beast table on-line

The Mars table occupies the middle registers of pages 43-45 of the Dresden Codex (according to the conventional page numbering).

The long count entry date

The

first

column on page 43b is headed with 3 Lamat and the Mars beast

glyph.

Below it is the number 9.19.8.15.0 and 3 Lamat again. Although

this

has the form of an ordinary long count, it is not. The tzolk'in

date

of 9.19.8.15.0 is not 3 Lamat. The number is

an example of what Thompson called a "long reckoning", counted from a

base

date prior to creation.

The

first

column on page 43b is headed with 3 Lamat and the Mars beast

glyph.

Below it is the number 9.19.8.15.0 and 3 Lamat again. Although

this

has the form of an ordinary long count, it is not. The tzolk'in

date

of 9.19.8.15.0 is not 3 Lamat. The number is

an example of what Thompson called a "long reckoning", counted from a

base

date prior to creation.

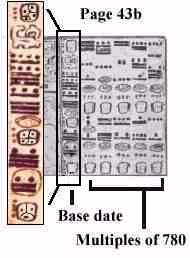

The base date for the calculation is given by the "ring number" below the long reckoning. This is 17.12. The k'in coefficient is circled with a red ring, and it is followed by 4 Ahaw, the tzolk'in date of the zero position of the long count. If the "long reckoning" is counted forward from 17.12 = 352 days prior to creation, it reaches the long count position 9.19.7.15.8 3 Lamat.

This is 26 March 818 AD in the Gregorian calendar (using the '85 correlation). It is likely intended to be an entry date into the Mars table. The rest of page 43b lists multiples of 780, and was presumably used to calculate entry dates later than 818 AD.

The base date of the Mars table, like the base dates of the Venus and eclipse tables, is in the Classical period, long before the Dresden Codex was compiled. Thus is is not certain that 9.19.7.15.8 3 Lamat, 26 March 818 AD, was ever used as a practical entry point into the table.

This entry date may have been calculated by subtracting multiples of the 780 day Mars period from a later base date.

For a fuller discussion of ring numbers, see Gregory Reddick, Ring and Serpent Numbers in the Dresden Codex

According to the Brickers, the almanac tracks Mars through 78 days of retrograde motion, starting at the "stationary point" when retrograde motion begins, on 3 Lamat. Since the period of retrograde motion was likely regarded as a critical time in the planet's career, it is not surprising that several stations of ritual significance appear to have been recognized during its course.

By extension of this logic, the remainder of the Mars period may have been divided into 78 day subdivisions by the scribes. However, the text and illustrations of the almanac may apply only to the critical period of retrograde motion.(10)

Retrograde motion and stationary points

The earth orbits the sun more rapidly than the outer planets. As earth passes an outer planet, the planet appears to reverse its motion along the ecliptic, a phenomenon known as retrograde motion. At the time when motion begins to reverse, the planet's position on the ecliptic appears to freeze for a time. This is called the first stationary point. At the end of the period of retrograde motion, the planet appears to stop again. This is the second stationary point.

The Brickers noted that the average period of retrograde motion of Mars is about 75 days. They suggested that the scribes may have regarded 78 days, one-tenth of the Mars period, as an idealized value of the period of retrograde motion. A similar modification of observation occurs in the Venus table, where the lengths of apparitions of the planet are contrived to to keep the rising and setting at tzolk'in dates with ritual significance. Because of difficulty in determining the instant at which a stationary point is reached, the 3 day "error" hypothesized by the Brickers is not observationally significant.

The synodic period of a planet is its apparent period of revolution with respect to the sun as seen from earth, or the time between identical configurations of the earth, sun, and planet. The synodic period of Mars can be counted as the time between successive episodes of retrograde motion. The sidereal period of a planet is the true period of revolution about the sun.

9.19.7.15.8 3 Lamat, 26 March 818 AD, is in fact closer to the first stationary point than to any other significant event in Mars' synodic period. It is not close enough, however, to have produced predictions of retrograde motion within the limits of observational error.

But this is not a fatal objection. The long count entry into the Venus table is no more accurate. In both cases, the recorded entry date is likely a theoretical throw-back, calculated by subtracting planetary periods from a later date without correction for rounding error.

Presumably, the throw-back entry dates were recorded for augural or ritual purposes.

Dennis Tedlock has made a convincing, though circumstantial, case that 9.19.7.15.8 3 Lamat does have astronomical significance, at least in the mythic world. The ring number 17.12 is, like its counterpart on the Venus pages, likely another throw-back entry point, a multiple of Mars periods subtracted from 9.19.7.15.8 3 Lamat to reach a theoretical stationary point prior to creation of the present world.

Tedlock believes it can be related to mythical dates recorded in the inscriptions of the Cross Group at Palenque:

"The birth of Hun Hunaphu, [first father] [on -8.5.0 according to the inscriptions] . . . precedes the first recorded rising of Venus as morning star [on -6.2.0 according to the Venus table] by 780 days, an interval equivalent to the average Martian synodic period. In the idealized world of mythic time, then, whatever Martian event occurred on -8.5.0, must have happened again on -6.2.0.

To determine the position of Mars on those two dates we can move forward to -17.12, at which point Mars (by the mythic reckoning of the Dresden Codex) should go into retrograde motion. The distance separating 8.5.0 and -17.12 is . . . three complete Martian periods plus 288 days.

Today's astronomers reckon Martian retrograde motion as beginning 292 days (on average) after helical rising, which leaves 4 days to account for . . . [but] the Dresden Mars table treats 78 days as the ideal interval for retrograde motion rather than 75 [thus] we can reduce the already small number of extra days to 2 or 3.

If the mythic event of -8.5.0 is indeed a helical rise of Mars, than -17.12 is a quite reasonable time for onset of retrograde motion . . . ."(11)

Ritual and augury

It

is likely

that the Mars table was used to time rituals and make auguries, but

because

little is known about the role of Mars in Maya myth, ritual, and

augury,

the details are far from certain. The texts in the almanac seem

to

be augural, and to have some features in common with the texts marking

the helical rise of Venus.

It

is likely

that the Mars table was used to time rituals and make auguries, but

because

little is known about the role of Mars in Maya myth, ritual, and

augury,

the details are far from certain. The texts in the almanac seem

to

be augural, and to have some features in common with the texts marking

the helical rise of Venus.

Each block of text above an image of the Mars beast begins with an identical phrase, consisting of a verb and the Mars beast glyph. The main sign of the verb is an ax pictograph, read from context in the inscriptions as "axed", "decapitated", or "damaged.".

A plausible transliteration is ch'ak. In the inscriptions, the ax verb is followed by the name of the person (usually a sacrificial victim) who is "axed". This suggests that the phrase should be translated as "was axed (damaged, sacrificed etc.), the Mars Beast".

Perhaps this refers to

retrograde

motion of the planet. The rest of each text block appears to contain

auguries.

References

Aveni, Anthony F. Skywatchers . (University of Texas Press, 2001)

Aveni, Anthony . Harvey Bricker and Victoria Bricker. "Ancient Maya documents concerning the movement of Mars". PNAS, Feb 13, 2001, Vol. 98 no. 4. on-line

Bricker,Victoria and Harvey Bricker. "The Mars Table in the Dresden Codex". Middle American Research Institute Publications 57, 1986.

"More on the Mars table in the Dresden Codex". Lat. Am. Antiq., 8:4, 1997.

Love, Bruce. "A Dresden Codex Mars table?". Lat. Am. Antiq., 6:4, 1995.

Dutting, Deiter and Anthony F. Aveni. "The 2 Cib 14 Mol Event in the Palenque Inscriptions". Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie 107, 1982.

Kelley, David. Deciphering the Maya Script. Univ. of Texas, 1976.

Seler, Eduard. Mexican Antiquities (translation of nine articles). Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 28, 1904.

Schele, Linda and David Freidel. A Forest of Kings. William Morrow, 1990.

Tedlock, Dennis. "Myth, Math, and the Problem of Correlation in Mayan Books", in Anthony F. Aveni, ed. The Sky in Mayan Literature. Oxford, 1992.

Thompson, Sir John Eric. A Commentary on the Dresden Codex. American Philosophical Society, Memoir no. 93, 1972.

Willson, R.W. Astronomical Notes on the Maya Codices. Papers Peabody Museum, Vol. 6, no. 3, 1924.