|

With all this, you might just be

wondering exactly what shape is the “Triangle.”

You would not be the first.

No two researchers or authors ever agreed, although most were in accord that

the Sargasso Sea and the area of the strict triangle between Miami, San Juan

and Bermuda embodies the greatest part.

Many have proposed an alternate nodal point, that is, Norfolk, Virginia,

calling to mind that Cape Hatteras has been known for centuries as the

“Graveyard of the Atlantic.” However, graveyard implies a burial place for

ships, where their rotting carcasses can still be seen.

And that is quite

true of Cape Hatteras. Many famous vessels can still be found on the bottom,

slammed by the great gales and thrashed by the reefs, like the Union

ironclad, Monitor, which foundered here.

But disappearance means no trace is

found, implying destruction on a complete and total scale, something beyond

even the great reefs and shoals of Cape Hatteras and her wild seas.

The seas off Norfolk are, of course, the Gulf Stream and the routes to

Bermuda or south to the Bahamas and Caribbean.

All the ships coming or going

to Panama and the East Coast pass by here, to Canada, New York, off to

Europe, wherever. The seas of the Carolinas are perfectly juxtapositioned to

put them in daily interplay with the greatest seaways of the Triangle.

But though these are hard waters, several mysteries share an uneasy grave

here with the rusted relics of the sea.

The freighter Southern Districts

passed by here in 1954 and vanished utterly, as have several yachts en route

to Bermuda, like Windfall or Dancing Feathers or L’Avenir. The 5 masted

cargo schooner, Carroll A. Derring, ghosted up upon the shores here in 1921,

totally shipshape but mysteriously deserted.

Captain John M. Waters, once head of Coast Guard Search and Rescue in

Washington D.C., wrote in his Rescue at Sea (Van Nostrand, 1966) about the

curious disappearance of a Coast Guard commander, James Reed Hinnant. He was

commander of the Coast Guard cutter Rockaway. It was a balmy night.

About

300 miles off Cape Hatteras, near the Sargasso Sea, the Rockaway’s propeller

became fouled. He ordered diving gear and search lights. He was an

experienced diver and was even commended for his diving under fire in the

Philippines during WWII.

Suited up, he went over the side to the propeller.

Dozens manned the rails and watched the brightened water, glowing from the

underwater spot light. After a while they tugged his line to see if he was

OK. However, there was no response.

The OD ordered it hauled in, yet it

would not budge.

The search for Hinnant was intense, but in the end it offered no clues but

this: his air hose and line were found fouled in the propeller. Capt. Waters

finishes the narrative:

“What could have happened to an experienced diver

only 10 feet below the surface? Had his retaining line and air hose fouled?

If so, he had only to release his weighted belt, take a deep pull of air,

flip off the mask, and surface. It is a simple and basic maneuver for a

diver. Many speculated that he had been hit by a shark.

There are many large

man eaters in that area, and they are attracted to light. Commander Hinnant

had been working beneath a large light, and a shark could have come in while

he was busy working on the screw. However, no sharks were seen at any time,

and there was no disturbance in the water, nor any evidence of a struggle.

No one saw him surface, though many men were watching the water at all

times. What happened to him that night will never be known.”

Mystery also befell a Navy KA-6 attack bomber in 1978 while 100 miles off

Norfolk.

The last words of the pilot, Lieutenant Paul Smyth, were: “Stand

By, we have a problem right now . . .” In the radar plot of the carrier John

F. Kennedy (Smyth’s intended destination), they continued to follow the jet

and attempt contact for 10 minutes without any response. Then the KA-6

suddenly vanished.

Shortly thereafter, another blip reappeared, tracking in

another direction, away from the carrier, then vanished off the radar scope

forever. There was never a trace found of the jet, nor any reason why Smyth

answered no calls in that period of time; no reason why there was no

automatic alarm, nor why they could not eject (ejection also triggers an

auto-alarm) And what was that second blip?

Three marines and three children departed in a launch off Surf City, North

Carolina, in 1985, only to vanish. The launch was later found . . . at the

end of a line of six unused life jackets. No explanation was found, and the

launch was towed back in.

Along with dozens of more examples, far too many to recite without being

repetitious, Norfolk or the Virginia Capes offer themselves as a point in

the “Triangle.” Premier sailor, Alan Villiers, noted this in his Posted

Missing (Scribners 1974) saying the Triangle lay between

Key West,

Chesapeake Bay and Bermuda.

|

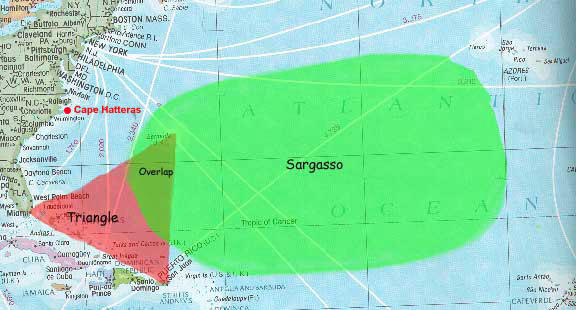

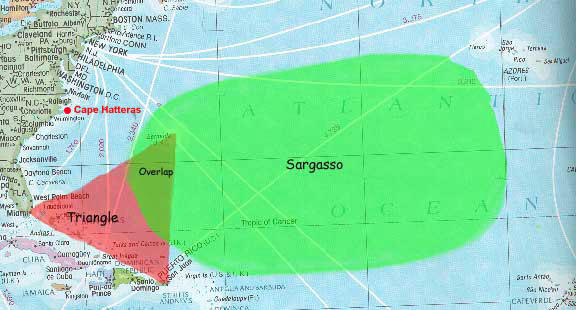

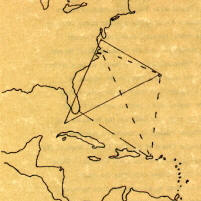

The standard triangle of

journalist Vincent Gaddis. Above this is superimposed the “vile

vortice” of biologist Ivan Sanderson. While Gaddis sought to

catalogue sea mysteries, Sanderson tried to use them to verify his

theories of areas of electromagnetic anomalies and underwater UFO

civilizations. |

However, it was Vincent

Gaddis who first tried to give shape to the area. In 1964 he wrote

an article for Argosy magazine, entitled “The Mystery of the Deadly

Bermuda Triangle.”

From that day on the sea of old mariner lore

began to be called by no other name. It was he who offered Miami,

San Juan, and Bermuda as the three nodal points.

Yet it wasn’t long

before this was challenged. John Wallace Spencer, from whom the term

“Limbo of the Lost” originates, wrote the first entire book devoted

to the subject (Limbo of the Lost, Phillips, 1969).

He believed it extended

from,

“. . . Cape May, New Jersey, to the edge of the continental

shelf. Following the shelf around Florida into the Gulf of Mexico,

it continues through Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, the Dominican Republic,

Puerto Rico, and other islands of the West Indies, and then comes up

again through the Bahamas... then up once more to

Bermuda.”

Naturalist, Ivan T. Sanderson, who studied several phenomena from

Bigfoot to UFOs, held a different view. He observed:

“The popular

idea has been that there is a roughly triangular area with sides

running from Bermuda to central Florida and thence to

Puerto Rico...

This is a glamorous

notion, but on proper analysis it does not stand up. It is not a

triangle, and its periphery is much greater than the one outlined

above.

In fact, the area... forms a large, sort of lozenge shaped

area... which extends from about 30º to 40º north latitude, and

from about 55º to 85º west.”

|

|

Author Richard Winer offered yet

another novel shape, stating in his Devil’s Triangle (1974):

“The Devil’s Triangle is not a triangle at all. It is a

trapezium, a four

sided area in which no two sides or angles are the same.”

He

concludes:

“And the first four letters of the word

trapezium more

than accurately describe it.”

There are any number of

other novel shapes which promote an author’s imagination more than

his knowledge of the Bermuda Triangle. But John Godwin (This

Baffling World) not only identified the area most accurately, but

also gave it its most humorous name, calling it the “Hoodoo Sea.”

To

add injury to insult, Vincent Gaddis later retracted his statement

because it implied the phenomenon had “boundaries,” although it is

hard to imagine how there can be a phenomenon if there are no

boundaries.

|

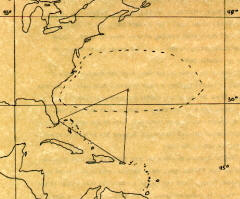

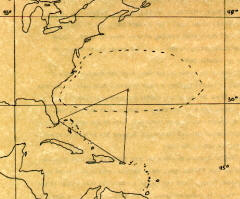

Three varied shapes: The

Trapezium of Richard Winer extends far into the Atlantic and

Sargasso Sea; Charles Berlitz’s triangle extends close to South

America; and the broken line represents John Spencer’s “Limbo of the

Lost.” |

|

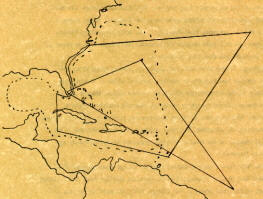

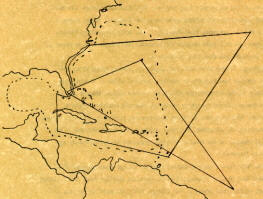

Drawing lines from the

major nodel points of Bermuda, Miami, San Juan and Norfolk creates

the “Sea of the Four Triangles.” This about covers John Godwin’s

“Hoodoo Sea.” |

It is therefore up to

the reader to decide, based upon the maps, which shape he/she

prefers.

One thing is certain: the “Triangle” is not a triangle at

all, but an amorphous body of water in the proximity of the

Sargasso Sea and West Indies.

|

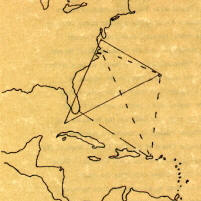

A rough estimate of

where major losses (marked by a triangle) may have occurred, based

on last known position or course followed.

|

|