Grains from

Siberian peat bog

may be remnants of the biggest Earth impact in

recorded history.

They came from outer space. Fragments of rock retrieved from a remote corner of Siberia could help to settle an enduring mystery: the cause of the Tunguska explosion.

On 30 June 1908, a powerful blast ripped open the sky near the Podkamennaya Tunguska river in Russia and flattened more than 2,000 square kilometers of forest. Eyewitnesses described a large object tearing through the atmosphere and exploding before reaching the ground, sending a wave of intense heat racing across the countryside.

At an estimated 3 to 5 megatons of TNT equivalent, it was the biggest impact event in recorded history. By comparison, the meteor that struck the Russian region of Chelyabinsk earlier this year 'merely' packed 460 kilotonnes of TNT equivalent.

Numerous scientific expeditions failed to recover any fragments that could be attributed conclusively to the object.

Hundreds of microscopic magnetic spheres have been found in the 1950s and 1960s in Tunguska soil samples, but there is continuing debate about whether they are the remnants of a vaporized meteor.

“There’s really not much out there, and nothing that’s definitively Tunguska,” says Phil Bland, a meteorite expert at Curtin University in Perth, Australia.

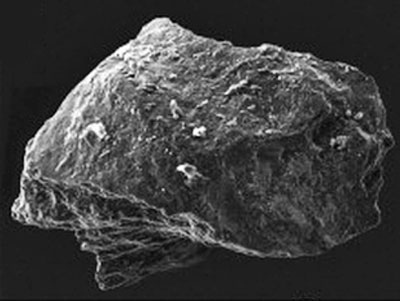

This rock fragment from a Siberian peat bog

appears to have been exposed to extreme temperatures and pressures,

possibly pointing to the violent impact of a meteor on the atmosphere.

Ref 1

The lack of samples has allowed wild speculation about the cause of the event, with some of the more esoteric explanations invoking antimatter and black holes.

But most geoscientists think that part of an asteroid, or perhaps a comet, broke away and fell to Earth as a meteor.

Now, researchers led by Victor Kvasnytsya at the Institute of Geochemistry, Mineralogy and Ore Formation of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine in Kiev say that they have found a smoking gun.

In what Kvasnytsya describes as the most detailed analysis yet of any candidate sample from the Tunguska event, the researchers conclude that their fragments of rock - each less than 1 millimeter wide - came from the iron-rich meteor that caused the blast.

The study was published late last month in Planetary and Space Science.1

“If these are Tunguska fragments, it could end any doubt that it was an asteroid impact,” says Gareth Collins, an Earth-impact researcher at Imperial College London.

“We would have convincing proof that this was an extraterrestrial event, and it would rule out a comet.”

Under pressure

Kvasnytsya says that Ukrainian scientist Mykola Kovalyukh, who died last year, collected the fragments in 1978 from a peat bog close to the epicenter of the blast.

Research on the fragments in the years following their discovery found that they contained a form of carbon called lonsdaleite, which has a crystal structure somewhere between graphite and diamond, and forms under extreme heat and pressure.

But the grains also contained less of the dense metal iridium than is typically found in meteorites - the meteor fragments that are actually recovered on the ground - so researchers had concluded that they were terrestrial rocks altered by the impact. The findings, published in the 1980s in Russian, went largely unnoticed by Western scientists at the time.

Kvasnytsya and his colleagues decided to take a closer look at the fragments using a battery of modern analytical techniques.

Transmission electron microscopy showed that the carbon grains were finely veined with iron-based minerals including troilite, schreibersite and the iron-nickel alloy taenite.

This patterning and combination of minerals is very similar to that in other iron-rich meteorites.

“The samples have almost the entire set of characteristic minerals of diamond-bearing meteorites,” says Kvasnytsya.

“An iron-rich, stony asteroid fits with our understanding of Tunguska,” says Collins.

Over the past 20 years, several modeling efforts have concluded that a stony asteroid was the only culprit that could have produced the effects reported on the ground. 2-3

However, a small but significant minority of scientists still backs the comet hypothesis, he adds.

Another one bites the dust

“They’ve got some interesting stuff here,” but the team does not yet have conclusive proof, says Bland.

The low levels of iridium and osmium in the samples are “a red flag” that raises doubts that the fragments originated in an asteroid, he says, and the peat sediment in which the samples were found has not been convincingly dated to 1908.

“We get a lot of meteorite material raining down on us all the time,” adds Bland.

Without samples of adjacent peat layers for comparison,

“it’s hard to be 100% sure that you’re not looking at that background”.

Confirming the meteor claim so long after the event will not be easy.

Geoscientists will take some convincing, not least because the subject attracts so much speculation. In May, a paper posted to the preprint server arXiv 4 claiming to have found pebbles from the Tunguska meteor was quickly dismissed by field specialists.

Kvasnytsya’s team hopes to do further tests on the grains, including measuring the ratios of key isotopes of helium and xenon, which could provide more evidence of the rocks' extraterrestrial origin.