|

4 - I Sing the Body

Holographic

You will hardly know who 1 am or

what I mean. But I shall be good health to you nevertheless. . .

.

• Walt Whitman,

“Song of Myself"

A sixty-one-year-old man we’ll call

Frank was diagnosed as having an almost always fatal form of throat

cancer and told he had less than a 5 percent chance of surviving.

His weight had dropped from 130 to 98 pounds. He was extremely weak,

could barely swallow his own saliva, and was having trouble

breathing. Indeed, his doctors had debated whether to give him

radiation therapy at all, because there was a distinct possibility

the treatment would only add to his discomfort without significantly

increasing his chances for survival. They decided to proceed anyway.

Then, to Frank’s great good fortune, Dr. O. Carl Simonton, a

radiation oncologist and medical director of the Cancer Counseling

and Research Center in Dallas, Texas, was asked to participate in

his treatment Simonton suggested that Frank himself could influence

the course of his own disease. Simonton then taught Frank a number

of relaxation and mental-imagery techniques he and his colleagues

had developed.

From that point on, three times a day, Frank pictured

the radiation he received as consisting of millions of tiny bullets

of energy bombarding his cells. He also visualized his cancer cells

as weaker and more confused than his normal cells, and thus unable

to repair the damage they suffered. Then he visualized his body’s

white blood cells, the soldiers of the immune system, coming in,

swarming over the dead and dying cancer cells, and carrying them to

his liver and kidneys to be flushed out of his body.

The results were dramatic and far exceeded what usually happened in

such cases when patients were treated solely with radiation. The

radiation treatments worked like magic. Frank experienced almost

none of the negative side effects - damage to skin and mucous

membranes - that normally accompanied such therapy. He regained his

lost weight and his strength, and in a mere two months all signs of

his cancer had vanished. Simonton believes Frank’s remarkable

recovery was due in large part to his daily regimen of visualization

exercises.

In a follow-up study, Simonton and his colleagues taught their

mental-imagery techniques to 159 patients with cancers considered

medically incurable. The expected survival time for such a patient

is twelve months. Four years later 63 of the patients were still

alive. Of those, 14 showed no evidence of disease, the cancers were

regressing in 12, and in 17 the disease was stable.

The average

survival time of the group as a whole was 24.4 months, over twice as

long as the national norm.1

Simonton has since conducted a number of similar studies, all with

positive results. Despite such promising findings, his work is still

considered controversial. For instance, critics argue that the

individuals who participate in Simonton’s studies are not “average”

patients. Many of them have sought Simonton out for the express

purpose of learning his techniques, and this shows that they already

have an extraordinary fighting spirit.

Nonetheless, many researchers

find Simonton’s results compelling enough to support his work, and

Simonton himself has set up the Simonton Cancer Center, a successful

research and treatment facility in Pacific Palisades, California,

devoted to teaching imagery techniques to patients who are fighting

various illnesses. The therapeutic use of imagery has also captured

the imagination of the public, and a recent survey revealed that it

was the fourth most frequently used alternative treatment for

cancer.2

How is it that an image formed in the mind can have an effect on

something as formidable as an incurable cancer? Not surprisingly the

holographic theory of the brain can be used to explain this

phenomenon as well. Psychologist Jeanne Achterberg, director of

research and rehabilitation science at the University of Texas

Health Science Center in Dallas, Texas, and one of the scientists

who helped develop the imagery techniques Simonton uses, believes it

is the holographic imaging capabilities of the brain that provide

the key.

As has been noted, all experiences are ultimately just neurophysiological

processes taking place in the brain. According to the holographic

model the reason we experience some things, such as emotions, as

internal realities and others, such as the songs of birds and the

barking of dogs, as external realities is because that is where the

brain localizes them when it creates the internal hologram that we

experience as reality.

However, as we have also seen, the brain

cannot always distinguish between what is “out there” and what it

believes to be “out there,” and that is why amputees sometimes have

phantom limb sensations. Put another way, in a brain that operates

holographically, the remembered image of a thing can have as much

impact on the senses as the thing itself.

It can also have an equally powerful effect on the body’s

physiology, a state of affairs that has been experienced firsthand

by anyone who has ever felt their heart race after imagining hugging

a loved one. Or anyone who has ever felt their palms grow sweaty

after conjuring up the memory of some unusually frightening

experience.

At first glance the fact that the body cannot always

distinguish between an imagined event and a real one may seem

strange, but when one takes the holographic model into account - a

model that asserts that all experiences, whether real or imagined,

are reduced to the same common language of holographically organized

wave forms - the situation becomes much less puzzling.

Or as Achterberg puts it,

“When images are regarded in the holographic

manner, their omnipotent influence on physical function logically

follows. The image, the behavior, and the physiological concomitants

are a unified aspect of the same phenomenon.”3

Bohm uses his idea of the implicate order, the deeper and nonlocal

level of existence from which our entire universe springs, to echo

the sentiment.

“Every action starts from an intention in the

implicate order. The imagination is already the creation of the

form; it already has the intention and the germs of all the

movements needed to carry it out And it affects the body and so on,

so that as creation takes place in that way from the subtler levels

of the implicate order, it goes through them until it manifests in

the explicate.”4

In other words, in the implicate order,

as in the brain itself, imagination and reality are ultimately

indistinguishable, and it should therefore come as no surprise to us

that images in the mind can ultimately manifest as realities in the

physical body.

Achterberg found that the physiological effects produced through the

use of imagery are not only powerful, but can also be extremely

specific. For example, the term white blood cell actually refers to

a number of different kinds of cell. In one study, Achterberg

decided to see if she could train individuals to increase the number

of only one particular type of white blood cell in their body. To do

this she taught one group of college students how to image a cell

known as a neutrophil, the major constituent of the white blood cell

population.

She trained a second group to image T-cells, a more

specialized kind of white blood cell. At the end of the study the

group that learned the neutrophil imagery had a significant increase

in the number of neutrophils in their body, but no change in the

number of T-cells. The group that learned to image T-cells had a

significant increase in the number of that kind of cell, but the

number of neutrophils in their body remained the same.5

Achterberg says that belief is also critical to a person’s health.

As she points out, virtually everyone who has had contact with the

medical world knows at least one story of a patient who was sent

home to die, but because they “believed” otherwise, they astounded

their doctors by completely recovering. In her fascinating book

Imagery in Healing she describes several of her own encounters with

such cases. In one, a woman was comatose on admission, paralyzed,

and diagnosed with a massive brain tumor.

She underwent surgery to

“debulk” her tumor (remove as much as is safely possible), but

because she was considered close to death, she was sent home without

receiving either radiation or chemotherapy.

Instead of promptly dying, the woman became stronger by the day. As

her biofeedback therapist, Achterberg was able to monitor the

woman’s progress, and by the end of sixteen months the woman showed

no evidence of cancer.

Why?

Although the woman was intelligent in a

worldly sense, she was only moderately educated and did not really

know the meaning of the word tumor - or the death sentence it

imparted. Hence, she did not believe she was going to die and

overcame her cancer with the same confidence and determination she’d

used to overcome every other illness in her life, says Achterberg.

When Achterberg saw her last, the woman no longer had any traces of

paralysis, had thrown away her leg braces and her cane, and had even

been out dancing a couple of times.6

(missing pages 86 and 87)

Breznitz found that the stress hormone levels in the soldiers’ blood

always reflected their estimates and not the actual distance they

had marched.10 In other

words, their bodies responded not to reality, but to what they were

imaging as reality.

According to Dr. Charles A. Garfield, a former National Aeronautics

and Space Administration (NASA) researcher and current president of

the Performance Sciences Institute in Berkeley, California, the

Soviets have extensively researched the relationship between imagery

and physical performance. In one study a phalanx of world-class

Soviet athletes was divided into four groups.

The first group spent

100 percent of their training time in training. The second spent 75

percent of their time training and 25 percent of their time

visualizing the exact movements and accomplishments they wanted to

achieve in their sport. The third spent 50 percent of their time

training and 50 percent visualizing, and the fourth spent 25 percent

training and 75 percent visualizing.

Unbelievably, at the 1980

Winter Games in Lake Placid, New York, the fourth group showed the

greatest improvement in performance, followed by groups three, two,

and one, in that order.11

Garfield, who has spent hundreds of hours interviewing athletes and

sports researchers around the world, says that the Soviets have

incorporated sophisticated imagery techniques into many of their

athletic programs and that they believe mental images act as

precursors in the process of generating neuromuscular impulses.

Garfield believes imagery works because movement is recorded

holographically in the brain.

In his book Peak Performance: Mental

Training Techniques of the World’s Greatest Athletes, he states,

“These images are holographic and function primarily at the

subliminal level. The holographic imaging mechanism enables you to

quickly solve spatial problems such as assembling a complex machine,

choreographing a dance routine, or running visual images of plays

through your mind.”12

Australian psychologist Alan Richardson has obtained similar results

with basketball players. He took three groups of basketball players

and tested their ability to make free throws. Then he instructed the

first group to spend twenty minutes a day practicing free throws. He

told the second group not to practice, and had the third group spend

twenty minutes a day visualizing that they were shooting perfect

baskets.

As might be expected, the group that did nothing showed no

improvement.

The first group improved 24 percent, but through the

power of imagery alone, the third group improved an astonishing 23

percent, almost as much as the group that practiced.13

The Lack of Division Between Health and

Illness

Physician Larry Dossey believes that imagery is not the only tool

the holographic mind can use to effect changes in the body.

Another

is simply the recognition of the unbroken wholeness of all things.

As Dossey observes, we have a tendency to view illness as external

to us. Disease comes from without and besieges us, upsetting our

well-being. But if space and time, and all other things in the

universe, are truly inseparable, then we cannot make a distinction

between health and disease.

How can we put this knowledge to practical use in our lives?

When we

stop seeing illness as something separate and instead view it as

part of a larger whole, as a milieu of behavior, diet, sleep,

exercise patterns, and various other relationships with the world at

large, we often get better, says Dossey. As evidence he calls

attention to a study in which chronic headache sufferers were asked

to keep a diary of the frequency and severity of their headaches.

Although the record was intended to be a first step in preparing the

headache sufferers for further treatment, most of the subjects found

that when they began to keep a diary, their headaches disappeared!14

In another experiment cited by Dossey, a group of epileptic children

and their families were videotaped as they interacted with one an

other. Occasionally, there were emotional outbursts during the

sessions, which were often followed by actual seizures. When the

children were shown the tapes and saw the relationship between these

emotional events and their seizures, they became almost

seizure-free.15

Why?.

"By keeping a diary or watching a videotape, the subjects were

able to see their condition in relationship to the larger pattern of

their lives. When this happens, illness can no longer be viewed “as

an” intruding disease originating elsewhere, but as part of a

process of living which can accurately be described as an unbroken

whole,” says Dossey. “When our focus is toward a principle of

relatedness and oneness, and away from fragmentation and isolation,

health en

sues.”16

Dossey feels the word patient is as misleading as the word particle.

Instead of being separate and fundamentally isolated biological

units, we are essentially dynamic processes and patterns that are no

more analyzable into parts than are electrons. More than this, we

are connected, connected to the forces that create both sickness and

health, to the beliefs of our society, to the attitudes of our

friends, our family, and our doctors, and to the images, beliefs,

and even the very words we use to apprehend the universe.

In a holographic universe we are also connected to our bodies, and

in the preceding pages we have seen some of the ways these

connections manifest themselves. But there are others, perhaps even

an infinity of others.

As Pribram states,

“If indeed every part of

our body is a reflection of the whole, then there must be all kinds

of mechanisms to control what’s going on. Nothing is firm at this

point”17

Given our ignorance

in the matter, instead of asking how the mind controls the body

holographic, perhaps a more important question is,

-

What is the

extent of this control?

-

Are there any limitations on it, and if so,

what are they?

That is the question to which we now turn our

attention.

The Healing Power of Nothing at All

Another medical phenomenon

that provides us with a tantalizing glimpse of the control the mind

has over the body is the placebo effect.

A placebo is any medical

treatment that has no specific action on the body but is given

either to humor a patient, or as a control in a double-blind

experiment, that is, a study in which one group of individuals is

given a real treatment and another group is given a fake treatment.

In such experiments neither the researchers nor the individuals

being tested know which group they are in so that the effects of the

real treatment can be assessed more accurately. Sugar pills are

often used as placebos in drug studies. So is saline solution

(distilled water with salt in it), although placebos need not always

be drugs. Many believe that any medical benefit derived from

crystals, copper bracelets, and other nontraditional remedies is

also due to the placebo effect.

Even surgery has been used as a placebo.

In the 1950s, angina

pectoris, recurrent pain in the chest and left arm due to decreased

blood flow to the heart, was commonly treated with surgery. Then

some resourceful doctors decided to conduct an experiment. Rather

than perform the customary surgery, which involved tying off the

mammary artery, they cut patients open and then simply sewed them

back up again. The patients who received the sham surgery reported

just as much relief as the patients who had the full surgery. The

full surgery, as it turned out, was only producing a placebo effect.18

Nonetheless, the success of the sham surgery indicates that

somewhere deep in all of us we have the ability to control angina

pectoris.

And that is not all. In the last half century the placebo effect has

been extensively researched in hundreds of different studies around

the world. We now know that on average 35 percent of all people who

receive a given placebo will experience a significant effect

although this number can vary greatly from situation to situation.

In addition to angina pectoris, conditions that have proved

responsive to placebo treatment include migraine headaches,

allergies, fever, the common cold, acne, asthma, warts, various

kinds of pain, nausea and seasickness, peptic ulcers, psychiatric

syndromes such as depression and anxiety, rheumatoid and

degenerative arthritis, diabetes, radiation sickness, Parkinsonism,

multiple sclerosis, and cancer.

Clearly these range from the not so serious to the life threatening,

but placebo effects on even the mildest conditions may involve

physiological changes that are near miraculous. Take, for example,

the lowly wart. Warts are a small tumorous growth on the skin caused

by a virus. They are also extremely easy to cure through the use of

placebos, as is evidenced by the nearly endless folk rituals - ritual

itself being a kind of placebo - that are used by various cultures to

get rid of them.

Lewis Thomas, president emeritus of

Memorial

Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, tells of one physician

who regularly rid his patients of warts simply by painting a

harmless purple dye on them.

Thomas feels that explaining this small

miracle by saying it’s just the unconscious mind at work doesn’t

begin to do the placebo effect justice.

“If my unconscious can

figure out how to manipulate the mechanisms needed for getting

around that virus, and for deploying all the various cells in the

correct order for tissue rejection, then all I have to say is that

my unconscious is a lot further along than I am,” he states.19

The effectiveness of a placebo in any given circumstance also varies

greatly. In nine double-blind studies comparing placebos to aspirin,

placebos proved to be 54 percent as effective as the actual

analgesic.20 From this one

might expect that placebos would be even less effective when

compared to a much stronger painkiller such as morphine, but this is

not the case.

In six double-blind studies placebos were found to be

56 percent as effective as morphine in relieving pain! 21

Why?

One factor that can affect the

effectiveness of a placebo is the method in which it is given.

Injections are generally perceived as more potent than pills, and

hence giving a placebo in an injection can enhance its

effectiveness.

Similarly, capsules are often seen as more effective

than tablets, and even the size, shape, and color of a pill can play

a role. In a study designed to determine the suggestive value of a

pill’s color, researchers found that people tend to view yellow or

orange pills as mood manipulators, either stimulants or depressants.

Dark red pills are assumed to be sedatives; lavender pills,

hallucinogens; and white pills, painkillers.22

Another factor is the attitude the doctor conveys when he prescribes

the placebo. Dr. David Sobel, a placebo specialist at Kaiser

Hospital, California, relates the story of a doctor treating an

asthma patient who was having an unusually difficult time keeping

his bronchial tubes open. The doctor ordered a sample of a potent

new medicine from a pharmaceutical company and gave it to the man.

Within minutes the man showed

spectacular improvement and breathed more easily. However, the next

time he had an attack, the doctor decided to see what would happen

if he gave the man a placebo. This time the man complained that

there must be something wrong with the prescription because it

didn’t completely eliminate his breathing difficulty. This convinced

the doctor that the sample drug was indeed a potent new asthma

medication - until he received a letter from the pharmaceutical

company informing him that instead of the new drug, they had

accidentally sent him a placebo.!

Apparently it

was the doctor’s unwitting enthusiasm for the first placebo, and not

the second, that accounted for the discrepancy.23

In terms of the holographic model, the man’s remarkable response to

the placebo asthma medication can again be explained by the mind/body’s ultimate inability to distinguish between an imagined reality

and a real one. The man believed he was being given a powerful new

asthma drug, and this belief had as dramatic a physiological effect

on his lungs as if he had been given a real drug.

Achterberg’s

warning that the neural holograms that impact on our health are

varied and multifaceted is also underscored by the fact that even

something as subtle as the doctor’s slightly different attitude (and

perhaps body language) while administering the two placebos was

enough to cause one to work and the other to fail. It is clear from

this that even information received subliminally can contribute

greatly to the beliefs and mental images that impact on our health.

One wonders how many drugs have worked (or not worked) because of

the attitude the doctor conveyed while administering them.

Tumors That Melt Like Snowballs on a

Hot Stove

Understanding the role such factors play in a placebo’s

effectiveness is important, for it shows how our ability to control

the body holographic is molded by our beliefs.

Our minds have the

power to get rid of warts, to clear our bronchial tubes, and to

mimic the painkilling ability of morphine, but because we are

unaware that we possess the power, we must be fooled into using it.

This might almost be comic if it were not for the tragedies that

often result from our ignorance of our own power.

No incident better illustrates this than a now famous case reported

by psychologist Bruno Klopfer. Klopfer was treating a man named

Wright who had advanced cancer of the lymph nodes. All standard

treatments had been exhausted, and Wright appeared to have little

time left. His neck, armpits, chest, abdomen, and groin were filled

with tumors the size of oranges, and his spleen and liver were so

enlarged that two quarts of milky fluid had to be drained out of his

chest every day.

But Wright did not want to die. He had heard about an exciting new

drug called Krebiozen, and he begged his doctor to let him try it.

At first his doctor refused because the drug was only being tried on

people with a life expectancy of at least three months. But Wright

was so unrelenting in his entreaties, his doctor finally gave in.

He

gave Wright an injection of Krebiozen on Friday, but in his heart of

hearts he did not expect Wright to last the weekend. Then the doctor

went home.

To his surprise, on the following Monday he found Wright out of bed

and walking around. Klopfer reported that his tumors had “melted

like snowballs on a hot stove” and were half their original size.

This was a far more rapid decrease in size than even the strongest

X-ray treatments could have accomplished. Ten days after Wright’s

first Krebiozen treatment, he left the hospital and was, as far as

his doctors could tell, cancer free. When he had entered the

hospital he had needed an oxygen mask to breathe, but when he left

he was well enough to fly his own plane at 12,000 feet with no

discomfort.

Wright remained well for about two months, but then articles began

to appear asserting that Krebiozen actually had no effect on cancer

of the lymph nodes. Wright, who was rigidly logical and scientific

in his thinking, became very depressed, suffered a relapse, and was

readmitted to the hospital. This time his physician decided to try

an experiment. He told Wright that Krebiozen was every bit as

effective as it had seemed, but that some of the initial supplies of

the drug had deteriorated during shipping. He explained, however,

that he had a new highly concentrated version of the drug and could

treat Wright with this.

Of course the physician did not have a new

version of the drug and intended to inject Wright with plain water.

To create the proper atmosphere he even went through an elaborate

procedure before injecting Wright with the placebo.

Again the results were dramatic. Tumor masses melted, chest fluid

vanished, and Wright was quickly back on his feet and feeling great.

He remained symptom-free for another two months, but then the

American Medical Association announced that a nationwide study of

Krebiozen had found the drug worthless in the treatment of cancer.

This time Wright’s faith was completely shattered.

His cancer

blossomed anew and he died two days later.24

Wright’s story is tragic, but it contains a powerful message: When

we are fortunate enough to bypass our disbelief and tap the healing

forces within us, we can cause tumors to melt away overnight.

In the case of Krebiozen only one person was involved, but there are

similar cases involving many more people. Take a chemotherapeutic

agent called cis-platinum. When cis-platinum first became available

it, too, was touted as a wonder drug, and 75 percent of the people

who received it benefited from the treatment. But after the initial

wave of excitement and the use of cis-platinum became more routine,

its rate of effectiveness dropped to about 25 to 30 percent.

Apparently most of the benefit obtained from

cis-platinum was due to

the placebo effect.25

Do Any Drugs Really Work?

Such incidents raise an important

question. If drugs such as Krebiozen and cis-platinum work when we

believe in them and stop working when we stop believing in them,

what does this imply about the nature of drugs in general?

This is a

difficult question to answer, but we do have some clues. For

instance, physician Herbert Benson of Harvard Medical School points

out that the vast majority of treatments prescribed prior to this

century, from leeching to consuming lizard’s blood, were useless,

but because of the placebo effect, they were no doubt helpful at

least some of the time.26

Benson, along with Dr. David P. McCallie, Jr., of Harvard’s

Thorn-dike Laboratory, reviewed studies of various treatments for

angina pectoris that have been prescribed over the years and

discovered that although remedies have come and gone, the success

rates - even for treatments that are now discredited - have always

remained high.27

From these

two observations it is evident that the placebo effect has played an

important role in medicine in the past, but does it still play a

role today? The answer, it seems, is yes. The federal Office of

Technology Assessment estimates that more than 75 percent of all

current medical treatments have not been subjected to sufficient

scientific scrutiny, a figure that suggests that doctors may still

be giving placebos and not know it (Benson, for one, believes that,

at the very least, many over-the-counter medications act primarily

as placebos).28

Given the evidence we have looked at so far, one might almost wonder

if all drugs are placebos. Clearly the answer is no. Many drugs are

effective whether we believe in them or not: Vitamin C gets rid of

scurvy, and insulin makes diabetics better even when they are

skeptical. But still the issue is not quite as clear-cut as it may

seem.

Consider the following.

In a 1962 experiment Drs. Harriet Linton and Robert Langs told test

subjects they were going to participate in a study of the effects of

LSD, but then gave them a placebo instead. Nonetheless, half an hour

after taking the placebo, the subjects began to experience the

classic symptoms of the actual drug, loss of control, supposed

insight into the meaning of existence, and so on. These “placebo

trips” lasted several hours.29

A few years later, in 1966, the now infamous Harvard psychologist

Richard Alpert journeyed to the East to look for holy men who could

offer him insight into the LSD experience. He found several who were

willing to sample the drug and, interestingly, received a variety of

reactions. One pundit told him it was good, but not as good as

meditation.

Another, a Tibetan lama, complained that it only gave

him a headache.

But the reaction that fascinated Alpert most came from a wizened

little holy man in the foothills of the Himalayas. Because the man

was over sixty, Alpert’s first inclination was to give him a gentle

dose of 50 to 75 micrograms. But the man was much more interested in

one of the 305 microgram pills Alpert had brought with him, a

relatively sizable dose.

Reluctantly, Alpert gave him one of the

pills, but still the man was not satisfied. With a twinkle in his

eye he requested another and then another and placed all 915

micrograms of LSD on his tongue, a massive dose by any standard, and

swallowed them (in comparison, the average dose Grof used in his

studies was about 200 micrograms).

Aghast, Alpert watched intently, expecting the man to start waving

his arms and whooping like a banshee, but instead he behaved as if

nothing had happened. He remained that way for the rest of the day,

his demeanor as serene and unperturbed as it always was, save for

the twinkling glances he occasionally tossed Alpert. The LSD

apparently had little or no effect on him.

Alpert was so moved by

the experience he gave up LSD, changed his name to Ram Dass, and

converted to mysticism.30

And so taking a placebo may well produce the same effect as taking

the real drug, and taking the real drug might produce no effect.

This topsy-turvy state of affairs has also been demonstrated in

experiments involving amphetamines. In one study, ten subjects were

placed in each of two rooms. In the first room, nine were given a

stimulating amphetamine and the tenth a sleep-producing barbiturate.

In the second room the situation was reversed.

In both instances,

the person singled out behaved exactly as his companions did. In the

first room instead of falling asleep the lone barbiturate taker

became animated and speedy, and in the second room the lone

amphetamine taker fell asleep.31

There is also a case on record of a man

addicted to the stimulant Ritalin, whose addiction is then

transferred to a placebo. In other words, the man’s doctor enabled

him to avoid all the usual unpleasantries of Ritalin withdrawal by

secretly replacing his prescription with sugar pills. Unfortunately

the man then went on to display an addiction to the placebo! 32

Such events are not limited to experimental situations. Placebos

also play a role in our everyday lives. Does caffeine keep you awake

at night? Research has shown that even an injection of caffeine

won’t keep caffeine-sensitive individuals awake if they believe they

are receiving a sedative.33

Has an antibiotic ever helped you get over a cold or sore throat? If

so, you were experiencing the placebo effect.

All colds are caused

by viruses, as are several types of sore throat, and antibiotics are

only effective against bacterial infections, not viral infections.

Have you ever experienced an unpleasant side effect after taking a

medication? In a study of a tranquilizer called mephenesin,

researchers found that 10 to 20 percent of the test subjects

experienced negative side effects - including nausea, itchy rash, and

heart palpitations - regardless of whether they were given the actual

drug or a placebo.* 34

* Of course I am by

all means not suggesting that all drug side effects are

the result of the placebo effect. Should you experience a negative

reaction to a drug, always consult a physician.

Similarly, in a recent study of a new

kind of chemotherapy, 30 percent of the individuals in the control

group, the group given placebos, lost their hair.35

So if you know someone who is taking chemotherapy, tell them to try

to be optimistic in their expectations. The mind is a powerful

thing.

In addition to offering us a glimpse of this power, placebos also

support a more holographic approach to understanding the mind/body

relationship. As health and nutrition columnist Jane Brody observes

in an article in the New York Times,

“The effectiveness of placebos

provides dramatic support for a ‘holistic’ view of the human

organism, a view that is receiving increasing attention in medical

research. This view holds that the mind and body continually

interact and are too closely interwoven to be treated as independent

entities.” 36

The placebo effect may also be affecting us in far vaster ways than

we realize, as is evidenced by a recent and extremely puzzling

medical mystery. If you have watched any television at all in the

last year or so, you have no doubt seen a blitzkrieg of commercials

promoting aspirin’s ability to decrease the risk of heart attack.

There is a good deal of convincing evidence to back this up,

otherwise television censors, who are real sticklers for accuracy

when it comes to medical claims in commercials, wouldn’t allow such

copy on the air. This is all well and good.

The only problem is that

aspirin doesn’t seem to have the same effect on people in England. A

six-year study of 5,139 British doctors revealed no evidence that

aspirin reduces the risk of heart attack.37

Is there a flaw in somebody’s research, or is it possible that some

kind of massive placebo effect is to blame?

Whatever the case, don’t

stop believing in the prophylactic benefits of aspirin. It still may

save your life.

The Health Implications of Multiple

Personality

Another condition that

graphically illustrates the mind’s power to affect the body is

Multiple Personality Disorder (MPD). In addition to possessing

different brain-wave patterns, the subpersonalities of a multiple

have a strong psychological separation from one another.

Each has his own name, age, memories, and abilities. Often each also

has his own style of handwriting, announced gender, cultural and

racial background, artistic talents, foreign language fluency, and

IQ.

Even more noteworthy are the biological changes that take place in a

multiple’s body when they switch personalities. Frequently a medical

condition possessed by one personality will mysteriously vanish when

another personality takes over.

Dr. Bennett Braun of the

International Society for the Study of Multiple Personality, in

Chicago, has documented a case in which all of a patient’s subpersonalities were allergic to orange juice, except one. If the

man drank orange juice when one of his allergic personalities was in

control, he would break out in a terrible rash. But if he switched

to his non-allergic personality, the rash would instantly start to

fade and he could drink orange juice freely.38

Dr. Francine Rowland, a Yale psychiatrist who specializes in

treating multiples, relates an even more striking incident

concerning one multiple’s reaction to a wasp sting. On the occasion

in question, the man showed up for his scheduled appointment with

Rowland with his eye completely swollen shut from a wasp sting.

Realizing he needed medical attention, Howland called an

ophthalmologist

Unfortunately, the soonest the opthalmologist could

see the man was an hour later, and because the man was in severe

pain, Howland decided to try something. As it turned out, one of the

man’s alternates was an “anesthetic personality” who felt absolutely

no pain. Howland had the anesthetic personality take control of the

body, and the pain ended. But something else also happened.

By the

time the man arrived at his appointment with the ophthalmologist,

the swelling was gone and his eye had returned to normal. Seeing no

need to treat him, the ophthalmologist sent him home.

After a while, however, the anesthetic personality relinquished

control of the body, and the man’s original personality returned,

along with all the pain and swelling of the wasp sting. The next day

he went back to the ophthalmologist to at last be treated.

Neither

Rowland nor her patient had told the ophthalmologist that the man

was a multiple, and after treating him, the ophthalmologist

telephoned Rowland.

“He thought time was playing tricks on him.”

Rowland laughed. “He just wanted to make sure that I had actually

called him the day before and he had not imagined it”39

Allergies are not the only thing multiples can switch on and off. If

there was any doubt as to the control the unconscious mind has over

drug effects, it is banished by the pharmacological wizardry of the

multiple.

By changing personalities, a multiple who is drunk can

instantly become sober. Different personalities also respond

differently to different drugs. Braun records a case in which 5

milligrams of diazepam, a tranquilizer, sedated one personality,

while 100 milligrams had little or no effect on another. Often one

or several of a multiple’s personalities are children, and if an

adult personality is given a drug and then a child’s personality

takes over, the adult dosage may be too much for the child and

result in an overdose.

It is also difficult to anesthetize some

multiples, and there are accounts of multiples waking up on the

operating table after one of their “unanesthetizable”

subpersonalities has taken over.

Other conditions that can vary from personality to personality

include scars, burn marks, cysts, and left- and right-handedness.

Visual acuity can differ, and some multiples have to carry two or

three different pairs of eyeglasses to accommodate their alternating

personalities. One personality can be color-blind and another not,

and even eye color can change. There are cases of women who have two

or three menstrual periods each month because each of their

subpersonalities has its own cycle.

Speech pathologist Christy

Ludlow has found that the voice pattern for each of a multiple’s

personalities is different, a feat that requires such a deep

physiological change that even the most accomplished actor cannot

alter his voice enough to disguise his voice pattern.40

One multiple, admitted to a hospital for diabetes, baffled her

doctors by showing no symptoms when one of her non-diabetic

personalities was in control.41

There are accounts of epilepsy coming and going with changes in

personality, and psychologist Robert A. Phillips, Jr., reports that

even tumors can appear and disappear (although he does not specify

what kind of tumors).42

Multiples also tend to heal faster than normal individuals. For

example, there are several cases on record of third-degree burns

healing with extraordinary rapidity. Most eerie of all, at least one

researcher - Dr. Cornelia Wilbur, the therapist whose pioneering

treatment of Sybil Dorsett was portrayed in the book Sybil - is

convinced that multiples don’t age as fast as other people.

How could such things be?

At a recent symposium on the multiple

personality syndrome, a multiple named Cassandra provided a possible

answer. Cassandra attributes her own rapid healing ability both to

the visualization techniques she practices and to something she

calls parallel processing. As she explained, even when her alternate

personalities are not in control of her body, they are still aware.

This enables her to “think” on a multitude of different channels at

once, to do things like work on several different term papers

simultaneously, and even “sleep” while other personalities prepare

her dinner and clean her house.

Hence, whereas normal people only do healing imagery exercises two

or three times a day, Cassandra does them around the clock. She even

has a subpersonality named Celese who possesses a thorough knowledge

of anatomy and physiology, and whose sole function is to spend

twenty-four hours a day meditating and imaging the body’s

well-being. According to Cassandra, it is this full-time attention

to her health that gives her an edge over normal people. Other

multiples have made similar claims.43

We are deeply attached to the inevitability of things. If we have

bad vision, we believe we will have bad vision for life, and if we

suffer from diabetes, we do not for a moment think our condition

might vanish with a change in mood or thought. But the phenomenon of

multiple personality challenges this belief and offers further

evidence of just how much our psychological states can affect the

body’s biology.

If the psyche of an individual with MPD is a kind of

multiple image hologram, it appears that the body is one as well,

and can switch from one biological state to another as rapidly as

the flutter of a deck of cards.

The systems of control that must be in place to account for such

capacities is mind-boggling and makes our ability to will away a

wart look pale. Allergic reaction to a wasp sting is a complex and

multi-faceted process and involves the organized activity of

antibodies, the production of histamine, the dilation and rupture of

blood vessels, the excessive release of immune substances, and so

on.

What unknown pathways of influence

enable the mind of a multiple to freeze all these processes in their

tracks? Or what allows them to suspend the effects of alcohol and

other drugs in the blood, or turn diabetes on and off? At the moment

we don’t know and must console ourselves with one simple fact. Once

a multiple has undergone therapy and in some way becomes whole

again, he or she can still make these switches at will.44

This suggests that somewhere in our

psyches we all have the ability to control these things.

And still

this is not all we can do.

Pregnancy, Organ Transplants, and

Tapping the Genetic Level

As we have seen, simple everyday belief can also have a powerful

effect on the body.

Of course most of us do not have the mental

discipline to completely control our beliefs (which is why doctors

must use placebos to fool us into tapping the healing forces within

us).

To regain that control we must first

understand the different types of belief that can affect us, for

these too offer their own unique window on the plasticity of the

mind/body relationship.

CULTURAL BELIEFS

One type of belief is imposed on us by our society. For example,

the people of the Trobriand Islands engage freely in sexual

relations before marriage, but premarital pregnancy is strongly

frowned upon. They use no form of contraception, and seldom if

ever resort to abortion. Yet premarital pregnancy is virtually

unknown. This suggests that, because of their cultural beliefs,

the unmarried women are unconsciously preventing themselves from

getting-pregnant.45

There is evidence that something similar may be going on in our

own culture. Almost everyone knows of a couple who have tried

unsuccessfully for years to have a child. They finally adopt,

and shortly thereafter the woman gets pregnant. Again this

suggests that finally having a child enabled the woman and/or

her husband to overcome some sort of inhibition that was

blocking the effects of her and/or his fertility.

The fears we share with the other members of our culture can

also affect us greatly. In the nineteenth century, tuberculosis

killed tens of thousands of people, but starting in the 1880s,

death rates began to plummet. Why? Previous to that decade no

one knew what caused TB, which gave it an aura of terrifying

mystery. But in 1882 Dr. Robert Koch made the momentous

discovery that TB was caused by a bacterium. Once this knowledge

reached the general public, death rates fell from 600 per

100,000 to 200 per 100,000, despite the fact that it would be

nearly half a century before an effective drug treatment could

be found.46

Fear apparently has been an important factor in the success

rates of organ transplants as well. In the 1950s kidney

transplants were only a tantalizing possibility. Then a doctor

in Chicago made what

seemed to be a successful transplant He published his findings,

and soon after other successful transplants took place around

the world. Then the first transplant failed. In fact, the doctor

discovered that the kidney had actually been rejected from the

start. But it did not matter.

Once transplant recipients

believed they could survive, they did, and success rates soared

beyond all expectations.47

THE BELIEFS WE EMBODY IN OUR ATTITUDES

Another way belief manifests in our lives is through our

attitudes. Studies have shown that the attitude an expectant

mother has toward her baby, and pregnancy in general, has a

direct correlation with the complications she will experience

during childbirth, as well as with the medical problems her

newborn infant will have after it is born.48

Indeed, in the past decade an avalanche of studies has poured in

demonstrating the effect our attitudes have on a host of medical

conditions. People who score high on tests designed to measure

hostility and aggression are seven times more likely to die from

heart problems than people who receive low scores.49

Married women have stronger immune systems than separated or

divorced women, and happily married women have even stronger

immune systems.50 People

with AIDS who display a fighting spirit live longer than

AIDS-infected individuals who have a passive attitude.51

People with cancer also live longer if they maintain a fighting

spirit,52 Pessimists get

more colds than optimists.53

Stress lowers the immune response;54

people who have just lost their spouse have an increased

incidence of illness and disease,55

and on and on.

THE BELIEFS WE EXPRESS THROUGH THE POWER OF OUR WILL

The types of belief we have examined so far can be viewed

largely as passive beliefs, beliefs we allow our culture or the

normal state of our thoughts to impose upon us.

Conscious belief

in the form of a steely and unswerving will can also be used to

sculpt and control the body holographic. In the 1970s, Jack

Schwarz, a Dutch-born author and lecturer, astounded researchers

in laboratories across the United States with his ability to

willfully control his body’s internal biological processes.

In studies conducted at the Menninger Foundation, the University

of California’s Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute, and

others, Schwarz astonished doctors by sticking mammoth six-inch sailmaker’s needles completely through his arms without

bleeding, without flinching, and without producing beta brain

waves (the type of brain waves normally produced when a person

is in pain). Even when the needles were removed, Schwara still

did not bleed, and the puncture holes closed tightly.

In

addition, Schwarz altered his brain-wave rhythms at will, held

burning cigarettes against his flesh without harming himself,

and even carried live coals around in his hands. He claims he

acquired these abilities when he was in a Nazi concentration

camp and had to learn how to control pain in order to withstand

the terrible beatings he endured. He believes anyone can learn

voluntary control of their body and thus gain responsibility for

his or her own health.55

Oddly enough, in 1947 another Dutchman demonstrated similar

abilities. The man’s name was Mirin Dajo, and in public

performances at the Corso Theater in Zurich, he left audiences

stunned. In plain view Dajo would have an assistant stick a

fencing foil completely through his body, clearly piercing vital

organs but causing Dajo no harm or pain. Like Schwarz, when the

foil was removed, Dajo did not bleed and only a faint red line

marked the spot where the foil had entered and exited.

Dajo’s performance proved so nerve-racking to his audiences that

eventually one spectator suffered a heart attack, and Dajo was

legally banned from performing in public. However, a Swiss

doctor named Hans Naegeli-Osjord learned of Dajo’s alleged

abilities and asked him if he would submit to scientific

scrutiny. Dajo agreed, and on May 31, 1947, he entered the

Zurich cantonal hospital.

In addition to Dr. Naegeli-Osjord, Dr.

Werner Brunner, the chief of surgery at the hospital, was also

present, as were numerous other doctors, students, and

journalists. Dajo bared his chest and concentrated, and then, in

full view of the assemblage, he had his assistant plunge the

foil through his body.

As always, no blood flowed and Dajo remained completely at ease.

But he was the only one smiling. The rest of the crowd had

turned to stone. By all rights, Dajo’s vital organs should have

been severely damaged, and his seeming good health was almost

too much for the doctors to bear. Filled with disbelief, they

asked Dajo if he would submit to an X ray. He agreed and without

apparent effort accompanied them up the stairs to the X-ray

room, the foil still through his abdomen.

The X ray was taken

and the result was undeniable. Dajo was indeed impaled. Finally,

a full twenty minutes after he had been pierced, the foil was

removed, leaving only two faint scars. Later, Dajo was tested by

scientists in Basel, and even let the doctors themselves run him

through with the foil. Dr. Naegeli-Osjord later related the

entire case to the German physicist Alfred Stelter, and Stelter

reports it in his book Psi-Heating.57

Such supernormal feats of control are not limited to the Dutch.

In the 1960s Gilbert Grosvenor, the president of the National

Geographic Society, his wife, Donna, and a team of Geographic

photographers visited a village in Ceylon to witness the alleged

miracles of a local wonderworker named Mohotty. It seems that as

a young boy Mohotty prayed to a Ceylonese divinity named

Kataragama and told the god that if he cleared Mohotty’s father

of a murder charge, he, Mohotty, would do yearly penance in

Kataragama’s honor. Mohotty’s father was cleared, and true to

his word, every year Mohotty did his penance.

This consisted of walking through fire and hot coals, piercing

his cheeks with skewers, driving skewers into his arms from

shoulder to wrist, sinking large hooks deep into his back, and

dragging an enormous sledge around a courtyard with ropes

attached to the hooks. As the Grosvenors later reported, the

hooks pulled the flesh in Mohotty’s back quite taut, and again

there was no sign of blood.

When Mohotty was finished and the

hooks were removed, there weren’t even any traces of wounds. The

Geographic team photographed this unnerving display and

published both pictures and an account of the incident in the

April 1966 issue of National Geographic.58

In 1967 Scientific American published a report about a similar

annual ritual in India. In that instance a different person was

chosen each year by the local community, and after a generous

amount of ceremony, two hooks large enough to hang a side of

beef on were buried in the victim’s back. Ropes that were pulled

through the eyes of the hooks were tied to the boom of an ox

cart, and the victim was then swung in huge areas over the fields

as a sacramental offering to the fertility gods.

When the hooks

were removed the victim was completely unharmed, there was no

blood, and literally no sign of any punctures in the flesh

itself.59

OUR UNCONSCIOUS BELIEFS

As we have seen, if we are not fortunate enough to have the

self-mastery of a Dajo or a Mohotty, another way of accessing

the healing force within us is to bypass the thick armor of

doubt and skepticism that exists in our conscious minds.

Being

tricked with a placebo is one way of accomplishing this.

Hypnosis is another. Like a surgeon reaching in and altering the

condition of an internal organ, a skilled hypnotherapist can

reach into our psyche and help us change the most important type

of belief of all, our unconscious beliefs.

Numerous studies have demonstrated irrefutably that under

hypnosis a person can influence processes usually considered

unconscious. For instance, like a multiple, deeply hypnotized

persons can control allergic reactions, blood flow patterns, and

nearsightedness. In addition, they can control heart rate, pain,

body temperature, and even will away some kinds of birthmarks.

Hypnosis can also be used to accomplish something that, in its

own way, is every bit as remarkable as suffering no injury after

a foil has been stuck through one’s abdomen.

That something involves a horribly disfiguring hereditary

condition known as

Brocq’s disease. Victims of Brocq’s disease

develop a thick, horny covering over their skin that resembles

the scales of a reptile. The skin can become so hardened and

rigid that even the slightest movement will cause it to crack

and bleed. Many of the so-called alligator-skinned people in

circus sideshows were actually individuals with Brocq’s disease,

and because of the risk of infection, victims of Brocq’s disease

used to have relatively short life-spans.

Brocq’s disease was incurable until 1951 when a sixteen-year-old

boy with an advanced case of the affliction was referred as a

last resort to a hypnotherapist named A. A. Mason at the Queen

Victoria Hospital in London. Mason discovered that the boy was a

good hypnotic subject and could easily be put into a deep state

of trance.

While the boy was in trance, Mason told him that his Brocq’s disease was healing and would soon be gone. Five days

later the scaly layer covering the boy’s left arm fell off,

revealing soft, healthy flesh beneath. By the end of ten days

the arm was completely normal. Mason and the boy continued to

work on different body areas until all of the scaly skin was

gone. The boy remained symptom-free for at least five years, at

which point Mason lost touch with him.60

This is extraordinary because Brocq’s disease is a genetic

condition, and getting rid of it involves more than just

controlling autonomic processes such as blood flow patterns and

various cells of the immune system. It means tapping into the master-plan, our DNA programming itself.

So, it would appear

that when we access the right strata of our beliefs, our minds

can override even our genetic makeup.

FIGURE 11.

A 1962 X ray showing

the degree to which Vittorio Michelli’s hip bone had disintegrated

as a result of his malignant sarcoma.

So little bone was

left that the ball of his upper leg was free-floating in a mass of

soft tissue, rendered as gray mist in the X ray.

FIGURE 12.

After a series of

baths in the spring at Lourdes, Michelli experienced a miraculous

healing.

His hip bone

completely regenerated over the course of several months, a feat

currently considered impossible by medical science.

This 1965 X ray shows

his miraculously restored hip joint.

[Source: Michel-Marie

Salmon, The Extraordinary Cure of Vittorio Michelli. Used by

permission]

THE BELIEFS EMBODIED IN OUR FAITH

Perhaps the most powerful types of belief of all are those

we express through spiritual faith. In 1962 a man named

Vittorio

Michelli was admitted to the Military Hospital of Verona, Italy,

with a large cancerous tumor on his left hip (see fig. 11).

So

dire was his prognosis that he was sent home without treatment,

and within ten months his hip had completely disintegrated,

leaving the bone of his upper leg floating in nothing more than

a mass of soft tissue. He was, quite literally, falling apart As

a last resort he traveled to Lourdes and had himself bathed in

the spring (by this time he was in a plaster cast, and his

movements were quite restricted).

Immediately on entering the

water he had a sensation of heat moving through his body. After

the bath his appetite returned and he felt renewed energy. He

had several more baths and then returned home.

Over the course of the next month he felt such an increasing

sense of well-being he insisted his doctors X-ray him again.

They discovered his tumor was smaller. They were so intrigued

they documented every step in this improvement. It was a good

thing because after Michelli’s tumor disappeared, his bone began

to regenerate, and the medical community generally views this as

an impossibility.

Within two months he was up and walking again,

and over the course of the next several years his bone

completely reconstructed itself (see fig. 12).

A dossier on Michelli’s case was sent to

the Vatican’s Medical Commission, an international panel of doctors

set up to investigate such matters, and after examining the evidence

the commission decided Michelli had indeed experienced a miracle.

As

the commission stated in its official report,

“A remarkable

reconstruction of the iliac bone and cavity has taken place. The X

rays made in 1964,1965,1968 and 1969 confirm categorically and

without doubt that an unforeseen and even overwhelming bone

reconstruction has taken place of a type unknown in the annals of

world medicine.” * 61

Was Michelli’s healing a miracle in the sense that it violated any

of the known laws of physics? Although the jury remains out on this

question, there seems no clear-cut reason to believe any laws were

violated.

* In a truly stunning example of

synchronicity, while I was in the middle of writing these very words

a letter armed in the mail informing me that a friend who lives in

Kauai, Hawaii, and whose hip had disintegrated due to cancer has

also experienced an “inexplicable” and complete regeneration of her

bone. The tools she employed to effect her recovery were

chemotherapy, extensive meditation, and imagery exercises. The story

of her healing has been reported in the Hawaiian newspapers.

Rather, Michelli’s healing may simply be due to natural processes we

do not yet understand. Given the phenomenal range of healing

capacities we have looked at so far, it is clear there are many

pathways of interaction between the mind and body that we do not yet

understand.

If Michelli’s healing was attributable to an undiscovered natural

process, we might better ask,

Why is the regeneration of bone so

rare and what triggered it in Michelli’s case?

It may be that bone

regeneration is rare because achieving it requires the accessing of

very deep levels of the psyche, levels usually not reached through

the normal activities of consciousness. This appears to be why

hypnosis is needed to bring about a remission of Brocq’s disease.

As

for what triggered Michelli’s healing, given the role belief plays

in so many examples of mind/body plasticity it is certainly a

primary suspect. Could it be that through his faith in the healing

power of Lourdes, Michelli somehow, either consciously or

serendipitously, effected his own cure?

There is strong evidence that belief, not divine intervention, is

the prime mover in at least some so-called miraculous occurrences.

Recall that Mohotty attained his supernormal self-control by praying

to Kata-ragama, and unless we are willing to accept the existence of

Katara-gama, Mohotty's abilities seem better explained by his deep

and abiding belief that he was divinely protected. The same seems to

be true of many miracles produced by Christian wonder-workers and

saints.

One Christian miracle that appears to be generated by the power of

the mind is stigmata. Most church scholars agree that St. Francis of

Assisi was the first person to manifest spontaneously the wounds of

the crucifixion, but since his death there have been literally

hundreds of other stigmatists. Although no two ascetics exhibit the

stigmata in quite the same way, all have one thing in common.

From

St. Francis on, all have had wounds on their hands and feet that

represent where Christ was nailed to the cross. This is not what one

would expect if stigmata were God-given. As parapsychologist D.

Scott Rogo, a member of the graduate faculty at John F. Kennedy

University in Orinda, California, points out, it was Roman custom to

place the nails through the wrists, and skeletal remains from the

time of Christ bear this out Nails inserted through the hands cannot

support the weight of a body hanging on a cross.62

Why did St. Francis and all the other stigmatists who came after him

believe the nail holes passed through the hands?

Because that is the way the wounds have

been depicted by artists since the eighth century. That the position

and even size and shape of stigmata have been influenced by art is

especially apparent in the case of an Italian stigmatist named Gemma Galgani, who died in 1903. Gemma’s

wounds precisely mirrored the stigmata on her own favorite crucifix.

Another researcher who believed stigmata are self-induced was

Herbert Thurston, an English priest who wrote several volumes on

miracles. In his tour de force The Physical Phenomena of Mysticism,

published posthumously in 1952, he listed several reasons why he

thought stigmata were a product of autosuggestion.

The size, shape,

and location of the wounds varies from stigmatist to stigmatist, an

inconsistency that indicates they are not derived from a common

source, i.e., the actual wounds of Christ.

A comparison of the

visions experienced by various stigmatists also shows little

consistency, suggesting that they are not reenactments of the

historical crucifixion, but are instead products of the stigmatists’

own minds. And perhaps most significant of all, a surprisingly large

percentage of stigmatists also suffered from hysteria, a fact

Thurston interpreted as a further indication that stigmata are the

side effect of a volatile and abnormally emotional psyche, and not

necessarily the product of an enlightened one.63

In view of such evidence it is small wonder that even some of the

more liberal members of the Catholic leadership believe stigmata are

the product of “mystical contemplation,” that is, that they are

created by the mind during periods of intense meditation.

If stigmata are products of autosuggestion, the range of control the

mind has over the body holographic must be expanded even further.

Like Mohotty’s wounds, stigmata can also heal with disconcerting

speed. The almost limitless plasticity of the body is further

evidenced in the ability of some stigmatists to grow nail-like

protuberances in the middle of their wounds.

Again, St. Francis was

the first to display this phenomenon.

According to Thomas of Celano,

an eyewitness to St. Francis’s stigmata and also his biographer:

“His hands and feet seemed pierced in the midst by nails. These

marks were round on the inner side of the hands and elongated on the

outer side, and certain small pieces of flesh were seen like the

ends of nails bent and driven back, projecting from the rest of the

flesh.”64

Another contemporary of St. Francis’s, St Bonaventura, also

witnessed the saint’s stigmata and said that the nails were so

clearly defined one could slip a finger under them and into the

wounds.

Although St. Francis’s nails appeared to be composed of

blackened and hardened flesh, they possessed another nail-like

quality. According to Thomas of Celano, if a nail were pressed on

one side, it instantly projected on the other side, just as it would

if it were a real nail being slid back and forth through the middle

of the hand!

Therese Neumann, the well-known Bavarian stigmatist who died in

1962, also had such nail-like protuberances. Like St. Francis’s they

were apparently formed of hardened skin. They were thoroughly

examined by several doctors and found to be structures that passed

completely through her hands and feet. Unlike St. Francis’s wounds,

which were open continuously, Neumann’s opened only periodically,

and when they stopped bleeding, a soft, membrane-like tissue quickly

grew over them.

Other stigmatists have displayed similarly profound alterations in

their bodies. Padre Pio, the famous Italian stigmatist who died in

1968, had stigmata wounds that passed completely through his hands.

A wound in his side was so deep that doctors who examined it were

afraid to measure it for fear of damaging his internal organs.

Venerable Giovanna Maria Solimani, an eighteenth-century Italian

stigmatist, had wounds in her hands deep enough to stick a key into.

As with all stigmatists’ wounds, hers never became decayed,

infected, or even inflamed.

And another eighteenth-century stigmatist, St. Veronica Giuliani, an abbess at a convent in Citta

di Castello in Umbria, Italy, had a large wound in her side that

would open and close on command.

Images Projected Outside the Brain

The holographic model has aroused the

interest of researchers in the Soviet Union, and two Soviet

psychologists, Dr. Alexander P. Dubrov and Dr. Veniamin N. Pushkin,

have written extensively on the idea.

They believe that the

frequency processing capabilities of the brain do not in and of

themselves prove the holographic nature of the images and thoughts

in the human mind. They have, however, suggested what might

constitute such proof.

Dubrov and Pushkin believe that if an example

could be found where the brain projected an image outside of itself,

the holographic nature of the mind would be convincingly

demonstrated.

Or to use their own words,

“Records of ejection of

psychophysical structures outside the brain would provide direct

evidence of brain holograms.”65

In fact, St. Veronica Giuliani seems to supply such evidence.

During

the last years of her life she became convinced that the images of

the Passion - a crown of thorns, three nails, a cross, and a sword - had

become emblazoned on her heart. She drew pictures of these and even

noted where they were located. After she died an autopsy revealed

that the symbols were indeed impressed on her heart exactly as she

had depicted them. The two doctors who performed the autopsy signed

sworn statements attesting to their finding.66

Other stigmatists have had similar experiences. St. Teresa of Avila

had a vision of an angel piercing her heart with a sword, and after

she died a deep fissure was found in her heart. Her heart, with the

miraculous sword wound still clearly visible, is now on display as a

relic in Alba de Tormes, Spain.67

A nineteenth-century French stigmatist named Marie-Julie Jahenny

kept seeing the image of a flower in her mind, and eventually a

picture of the flower appeared on her breast. It remained there

twenty years.68

Nor are such

abilities limited to stigmatists. In 1913 a twelve-year-old girl

from the village of Bussus-Bus-Suel, near Abbeville, France, made

headlines when it was discovered that she could consciously command

images, such as pictures of dogs and horses, to appear on her arms,

legs, and shoulders. She could also produce words, and when someone

asked her a question the answer would instantly appear on her skin.69

Surely such demonstrations are examples of the ejection of

psychophysical structures outside the brain. In fact, in a way

stigmata themselves, especially those in which the flesh has formed

into nail-like protrusions, are examples of the brain projecting

images outside itself and impressing them in the soft clay of the

body holographic.

Dr. Michael Grosso, a philosopher at Jersey City

State College who has written extensively on the subject of

miracles, has also arrived at this conclusion.

Grosso, who traveled

to Italy to study Padre Pio’s stigmata firsthand, states,

“One of

the categories in my attempt to analyze Padre Pio is to say that he

had an ability to symbolically transform physical reality. In other

words, the level of consciousness he was operating at enabled him to

transform physical reality in the light of certain symbolic ideas.

For example, he identified with the wounds of the crucifixion and

his body became permeable to those psychic symbols, gradually

assuming their form.”70

So it appears that through the use of images, the brain can tell the

body what to do, including telling it to make more images. Images

making images. Two mirrors reflecting each other infinitely.

Such is

the nature of the mind/body relationship in a holographic universe.

Laws Both Known and Unknown

At the beginning of this chapter, I said that instead of examining

the various mechanisms the mind uses to control the body, the

chapter would be devoted primarily to exploring the range of this

control. In doing so I did not mean to deny or diminish the

importance of such mechanisms.

They are crucial to our understanding

of the mind/body relationship, and new discoveries in this area

seem to appear every day.

For example, at a recent conference on psychoneuroimmunology - a new

science that studies the way the mind (psycho), the nervous system (neuro),

and the immune system (immunology) interact - Candace Pert, chief of

brain biochemistry at the National Institute of Mental Health,

announced that immune cells have neuropeptide receptors.

Neuropeptides are molecules the brain uses to communicate, the

brain’s telegrams, if you will. There was a time when it was

believed that neuropeptides could only be found in the brain.

But

the existence of receptors (telegram receivers) on the cells in our

immune system implies that the immune system is not separate from

but is an extension of the brain. Neuropeptides have also been found

in various other parts of the body, leading Pert to admit that she

can no longer tell where the brain leaves off and the body begins.71

I have excluded such particulars, not only because 1 felt examining

the extent to which the mind can shape and control the body was more

relevant to the discussion at hand, but also because the biological

processes responsible for mind/body interactions are too vast a

subject for this book. At the beginning of the section on miracles I

said there was no clear-cut reason to believe Michelli’s bone

regeneration could not be explained by our current understanding of

physics.

This is less true of stigmata. It also appears to be very

much not true of various paranormal phenomena reported by credible

individuals throughout history, and in recent times by various

biologists, physicists, and other researchers.

In this chapter we have looked at astounding things the mind can do

that, although not fully understood, do not seem to violate any of

the known laws of physics. In the next chapter we will look at some

of the things the mind can do that cannot be explained by our

current scientific understandings. As we will see, the holographic

idea may shed light in these areas as well. Venturing into these

territories will occasionally involve treading on what might at

first seem to be shaky ground and examining phenomena even more

dizzying and incredible than Mohotty’s rapidly healing wounds and

the images on St. Veronica Giuliani’s heart.

But again we will find

that, despite their daunting nature, science is also beginning to

make inroads into these territories.

Acupuncture Microsystems and the Little

Man in the Ear

Before closing, one last piece of evidence of the body’s holographic

nature deserves to be mentioned. The ancient Chinese art of

acupuncture is based on the idea that every organ and bone in the

body is connected to specific points on the body’s surface.

By

activating these acupuncture points, with either needles or some

other form of stimulation, it is believed that diseases and

imbalances affecting the parts of the body connected to the points

can be alleviated and even cured. There are over a thousand

acupuncture points organized in imaginary lines called meridians on

the body’s surface.

Although still controversial, acupuncture is

gaining acceptance in the medical community and has even been used

successfully to treat chronic back pain in racehorses.

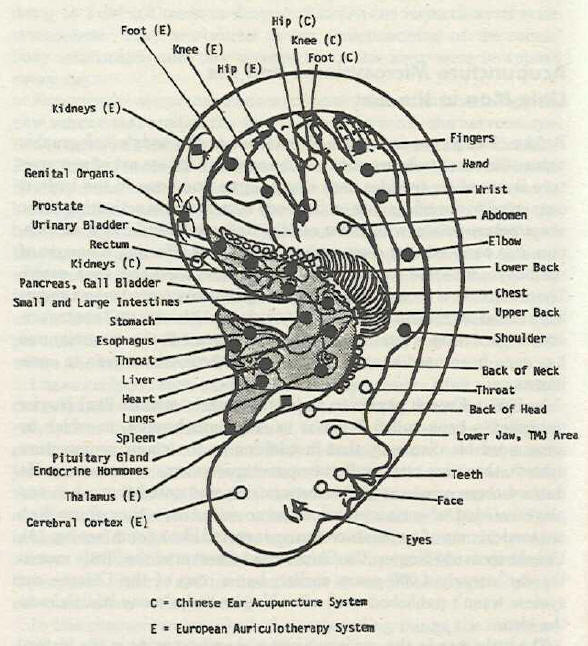

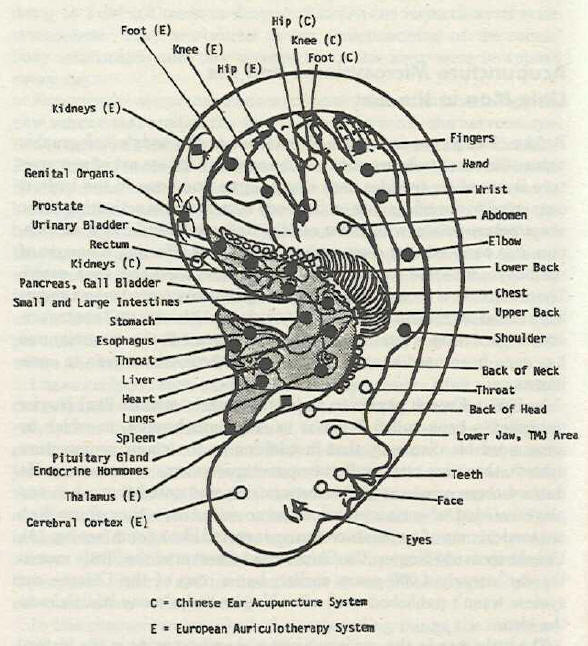

In 1957 a French physician and acupuncturist named Paul Nogier

published a book called Treatise of Auriculotkerapy, in which he

announced his discovery that in addition to the major acupuncture

system, there are two smaller acupuncture systems on both ears. He

dubbed these acupuncture microsystems and noted that when one played

a kind of connect-the-dots game with them, they formed an anatomical

map of a miniature human inverted like a fetus (see fig. 13).

Unbeknownst to Nogier, the Chinese had discovered the “little man in