|

from

NYTimes Website

guard the entrance of the Hoh Rain Forest, which sits within the Olympic National Park in Washington State. Credit Mitch Epstein

Washington State's Hoh Rain Forest, a poet searches for the rare peace that true silence can offer.

It stretches down coastal Washington and east toward Seattle on a thumb of land known as the Olympic Peninsula, some 60 miles long by 90 miles wide.

Around a three-hour ride by car from Seattle, it feels much farther, as if you have passed into an otherworldly realm.

Within it are volcanic beaches scattered with the remains of massive Sitka spruces, evergreen-crowded mountains, broad, flat valleys and the Hoh Rain Forest, through which 12 miles of hiking trails and the glacier-formed Hoh River run.

The Park, in total nearly a million acres, is home to what may be the most complex ecosystem in the United States, teeming with big-leaf maples, lichens, alders, liverworts, Monkey flowers, licorice ferns, club mosses, herbs, grasses and shrubs of remarkable abundance.

Today, thanks to federal protections, it is home to some of the largest remaining stands of old-growth forest in the continental U.S. It was an unusually warm and sunny day in August when I arrived in Washington.

I was walking the grounds of my hotel in Kalaloch Beach, less than an hour's drive from the rain forest, when I heard another guest call out.

I climbed up into the gazebo beside him and looked where he was pointing, at the vast, pounding ocean. A delicate spout of water breached the air. And then another. And another...

And then - a fin of an orca arcing over a wave.

adorns the towering big-leaf maple trees on the Maple Glade Trail, which is surrounded by a field of sword ferns. Credit Mitch Epstein

I hurried down to the beach.

The dark gray sand was velvety and warm. I walked past beached jellyfish and oyster shells and the slender bones of sea gulls. Before me was nothing but ocean - no ships, no airplanes, no buildings.

The huge noise of ocean and nothing but ocean was profound, a silence in its own right, which seemed odd as I thought about it - how can noise feel like silence?

Perhaps because its quality is continuous, soothing, allowing immersion. Listening, it seemed I was on the verge of some feeling or fresh understanding.

As the sensation crested, a huge orca lifted up out of the water, baring its smooth gray back, and for a moment I felt its weight settle on me.

A Journey Into Silence - The Hoh Rain

Forest

to the hush of Washington's Hoh Rain Forest, one of the quietest places in the U.S. By CLAYTON COTTERELL on Publish Date November 8, 2017. Photo by Clayton Cotterell.

I'd had a year that drained me emotionally and physically in ways I had no words for.

My father had been diagnosed with advanced lymphoma when my son was three months old; unable to care for himself, he came to live briefly with my family in our apartment in Brooklyn.

After months of chemotherapy he was better, but those days, weeks and months had been harrowing, hectic ones of visits to the doctor, calls to the insurance company and searches for food that might appeal to a finicky patient, all while caring for an increasingly needy baby.

I was behind on a book that required a lot of careful reflection, and I, too, was recovering from a long illness. When I returned from a month-long work trip with my son in late July, I was exhausted, unwell and snappish.

I desperately needed some quiet. At my husband's urging, I

flew to Seattle alone.

Here, the absence of sound is complete.

There are indeed few planes crossing the vast sky overhead, and on the less populated trails I walked during my visit I saw few other tourists or cars.

Around me, the sun filtered through dense canopies of leaves, and mosses hung, beardlike, from Sitka spruces and Douglas firs, turning the landscape into a Seussian fantasia.

Sword ferns, their leaves delicate and precise, formed coronas at the base of the massive spruce trunks. (A less martial mind might have named them after Victorian feather hairpieces rather than weaponry.)

Twelve to 14 feet of rain fall here annually, and the plant life is monumental:

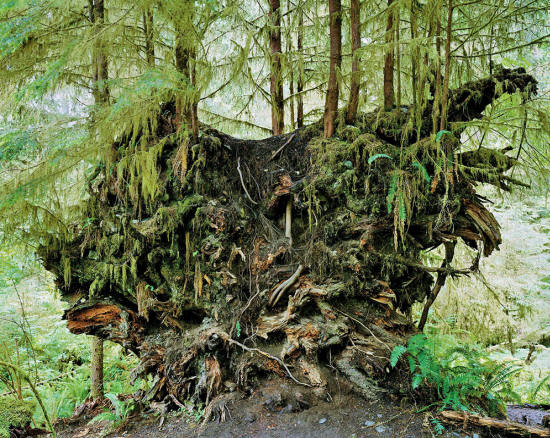

of a felled Sitka spruce on the Spruce Nature Trail.

Credit Mitch Epstein

I was loud inside, too, a cacophony of swirling

worries, nagging to-dos and then - beneath all that - a layer of

thoughts I hadn't had time to think in months.

Entering the quiet spaces of woodlands, as the novelist John Fowles once put it,

I sank into a medium where impressions arrived more slowly - and more completely.

What I heard, oddly, was distance. An insect far to my left on the mossy floor; a gray jay, maybe 50 yards away; and, even farther, the Hoh River, its waters a quiet, claylike, alluvial blue, stained by the rocky beaches banking it.

When I finally came to it, a herd of elk was resting dreamily in the sun, curled against one another.

As I watched, one woke, wobbled up onto its oversize legs, and made his way to the river to drink:

I stood there, breathing, taking in, being.

I'd come here to try doing just that - to find a willful silence.

My tense, raised shoulders slumped. I felt my body relax and my breathing slow.

Sitting on the rocks by the river, letting the sun flush my skin a warm pink, I realized that all summer I'd barely even registered the overwhelming sensation of heat, the way it makes you both sleepy and attuned to the tiniest flecks of sound around you, the pulse flicking in your wrist.

in the Olympic National Park; nearby is the Hoh Rain Forest, one of the quietest places in the United States. Credit Mitch Epstein

The world gets noisier by the day. More of us inhabit cities or population-dense areas than ever before, and car and plane traffic is steadily increasing.

The World Health Organization

recommends a maximum threshold of 40 decibels at night for healthy

sleep - one that's easily exceeded by spikes of noise from a truck

braking on the street or the roar of a low-flying plane.

The email

dinging on your desktop, the text that has to be answered while

you're on the freeway, the Twitter troll you can't stop yourself

from answering - it's no wonder we crave silence.

Concerned about,

In his book "Wear and Tear, or Hints for the Overworked" - published not five years ago, but in 1871 - S. Weir Mitchell diagnosed an epidemic of "hysteria" and "neurasthenia" among 19th-century Americans, worrying that modern life's stimulation was overtaxing them.

In other words,

neurasthenia was thought to be a disease of nerves over-stimulated by

the pressures of work, leading to fatigue.

Driftwood washes ashore on Ruby Beach, west of the Hoh Rain Forest.

Credit Mitch Epstein

Loud sounds arouse parts of our brains connected to fear, which in turn trigger a spike in blood pressure and stress hormones like cortisol.

These adaptive mechanisms helped our ancestors avoid, say, a bear attack. But if they're triggered day after day, they take a toll on our cardiovascular system.

Today,

your flexible health-care spending account is likely to list

earplugs alongside crutches and knee braces as a qualified medical

expense.

Other studies show that children who attend school near airports have poorer results on memory and reading-comprehension tests.

Ironically, all the magazine articles I kept encountering about the dangers of noise pollution had only been contributing to the noise in my head.

Calling for calm, they produced in its place an anxiety-inducing hum:

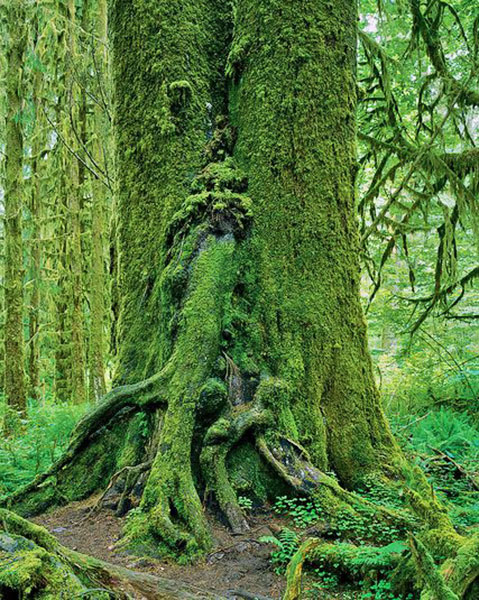

A large Sitka spruce covered in moss.

Credit Mitch Epstein

Silence is peaceful because it reduces stimulation. And silent places tend to be slower places.

As I sat by the river in the rain forest, in rushed all the thoughts that noise had blotted out, and held at bay.

I felt like an iPhone trying to download a huge cache of emails and texts after a long airplane flight:

But if silence is so peaceful, I wondered, why do many of us choose to live in busy, noisy cities?

Ours is a poetic dilemma:

After all, silence allows troubling realities:

The truest kind of silence is the ultimate one. Is that why we choose to live in noise, through centuries of complaining about it?

Adrift in it, we can duck confrontation with the metaphysical and the existential:

The next day, up the coast at Ruby Beach, about 30 miles west of the rain forest, I walked for miles at low tide.

Cormorants wheeled raucously around the peak of an island headland gnawed into existence by waves pounding it over thousands of years. They had left only the hard core of volcanic rock behind, a high isle that becomes accessible at low tide.

In the distance children were cart-wheeling on the sand. I sat on a piece of driftwood - a huge fallen Sitka, dried out by years on the beach.

Though it was noon and the sun was strong, mist clung to the headland, blanketing the beach like something from Emily Brontë. It was the kind of landscape that promised transformation, a wardrobe opening onto Narnia.

I noticed two fallen trees whose root systems were intertwined, so entangled it would be impossible to separate them without damaging them both. Instead of revving like an engine trying to drive ever onward, my mind slowed, slinking sideways and inward.

Entering a cove, I realized just how

habituated I am to noise when my mind kept interpreting the loud

waves as the roar of engines.

Paradoxically, though, during the quiet days I spent in Olympic Park, I found myself becoming,

...as Prochnik put it, describing a Quaker meeting he once attended.

Perhaps that's because the park is a public space.

A national reserve, it is meant for all of us,

unlike commercial quiet spaces where the emphasis is on personal

renewal. In my case, I was reminded of all the "countless silken

ties," as Robert Frost wrote, that keep us bonded to those around

us.

These thoughts were like music.

Rather than me having them, they were having me, and I climbed atop a pile of beach logs - enormous spruces, some 50 feet long, piled up like matchsticks by the roaring ocean - and let the driftwood warm my feet and the silence pool in my ears.

To hear ourselves, we sometimes have to flee ourselves, diving into silence until we're uncomfortably alone with the noise within...

|