|

by Victoria Jaggard

from

NationalGeographic Website explore the massive beams of selenite

inside

the Cave of Crystals in Naica mine.

National Geographic Creative the microbes are likely new to science and may be up to 50,000 years old, a NASA researcher says.

Creatures that thrive on iron, sulfur, and other chemicals have been found trapped inside giant crystals deep in a Mexican cave.

The microbial life-forms

are most likely new to science, and if the researchers who found

them are correct, the organisms are still active even though they

have been slumbering for tens of thousands of years.

for video, click above image

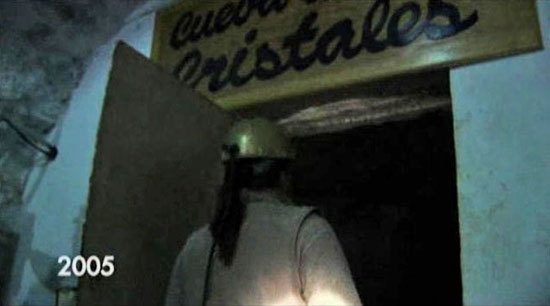

Exploring a

Deadly Cave to both explore and film the Cave of Crystals in the midst of crippling heat and humidity.

At the same time, the microbes raise some serious concerns about efforts to explore other worlds in our solar system and hunt for alien life, she says.

NASA takes many rigorous steps to sterilize spacecraft when necessary, but there are always risks that a mission to drill into another world could carry invasive - and highly durable - Earth creatures along for the ride.

Bubble Bugs

The microbes are adapted to survive in the extreme environments inside the Cave of Crystals, part of the Naica mine in the northern state of Chihuahua.

Operations to haul up lead and silver involved pumping groundwater out of the vast underground caverns, which revealed a labyrinth of massive milky-white crystals, some reaching more than 30 feet long.

toward the caverns of Naica

mine. National Geographic Creative

Penelope Boston took samples from pockets of fluid trapped inside the crystals in 2008 and 2009, under the auspices of New Mexico Tech.

Her team was able to "wake up" dormant microbes in that fluid and grow cultures, she revealed today at the meeting. The organisms are genetically distinct from anything known on Earth, according to her team's analysis, although they are most similar to other microbes found in caves and volcanic terrain.

Previous work dated the oldest crystals in the cave at half a million years.

Based on those calculations for the crystal growth rate, her team thinks the organisms they have growing in the lab had been inside their glittering cocoons for somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 years.

The work is currently being written up for publication and has not yet gone through the peer-review process, the standard first step in verifying a scientific find.

That makes it hard for other experts to say much about the claim for now.

For instance, other scientists have reported on ancient microbial life found in glacial ice, encased in amber, and trapped in salt crystals.

A gypsum crystal

creates an otherworldy effect inside the mine. National Geographic Creative

Part of the problem is that no one is sure how long life of any kind can survive when dormant.

Even sleeping organisms need food eventually or their cells will start to degrade, and scientists don't yet know if these hardy microbes can slow down their metabolism just enough to survive for millennia.

It's possible the organisms from Naica are eking out a living using the limited energy sources in the fluids in which they were found, Brent Christner adds:

Young Interlopers?

But there's also a chance that the Naica microbes didn't come from inside the crystals at all, but from the pools of water surrounding them.

In 2013, researchers in France and Spain reported the discovery of microbial life in hot, saline springs deep inside the Naica system.

These modern-day microbes also get their energy from chemicals in the subsurface and are also genetically distinct from known microbial species.

Naica mine is once again flooded with groundwater,

and the giant crystals are free to

keep growing. National Geographic Creative

Boston notes that her team took a variety of steps to try and avoid contamination, including wearing protective suits, sterilizing their drills, and sterilizing the surfaces of the crystals with hydrogen peroxide and, in some cases, fire.

That gives the team additional confidence that they are seeing organisms from inside the crystals.

Unfortunately, going back to the cave to collect more samples would be a tricky task. The mine stopped being profitable and operations at Naica have ceased, so the crystal cave is once more flooded with groundwater.

But Boston notes that the cultures her team collected are still actively growing, and she hopes other scientists will keep studying the creatures.

The microbes her team collected, she adds, are,

|