|

October 09, 2016

from

MessageToEagle Website

Scientists at the University of Chicago have discovered a very large

part of our planet's continental crust that was there 60 million

years ago is missing from the Earth's surface.

Three geoscientists examined the

collision of Eurasia and India, which began about 40 to 60 million

years ago.

During the collisions the Himalayas were

created and the process is still in slow progress.

The Himalayas

Using cutting-edge computational software, the scientists computed

with unprecedented precision the amount of landmass, or "continental

crust," before and after the collision.

The results were truly surprising.

"What we found is that half of the

mass that was there 60 million years ago is missing from the

earth's surface today," said Miquela Ingalls, a graduate student

in geophysical sciences who led the project as part of her

doctoral work.

The loss of so much mass could be

possible if the missing chunk had gone back down into the Earth's

mantle...

However, from a scientific point of

view there are problems with this theory and the researchers

considered it more or less impossible on such a scale.

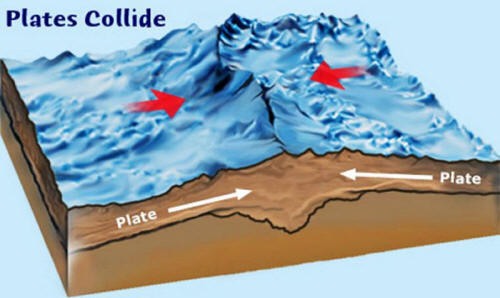

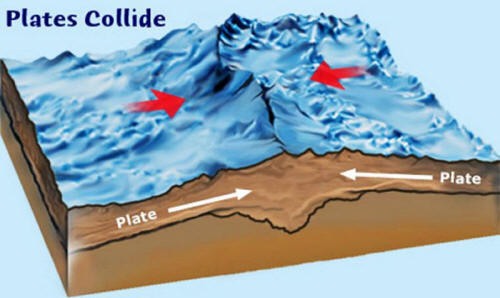

When tectonic plates come together, something has to give.

According to

plate tectonic theory, the surface

of the Earth comprises a mosaic of about a dozen rigid plates in

relative motion.

These plates move atop the upper mantle, and plates topped with

thicker, more buoyant continental crust ride higher than those

topped with thinner oceanic crust. Oceanic crust can dip and slide

into the mantle, where it eventually mixes together with the mantle

material.

But continental crust like that involved

in the Eurasia-India collision is less dense, and geologists have

long believed that when it meets the mantle, it is pushed back up

like a beach ball in water, never mixing back in.

"We're taught in Geology 101 that

continental crust is buoyant and can't descend into the mantle,"

Ingalls said.

The new results throw that idea out the

window.

"We really have significant amounts

of crust that have disappeared from the crustal reservoir, and

the only place that it can go is into the mantle," said David

Rowley, a professor in geophysical sciences who is one of

Ingalls' advisors and a collaborator on the project.

"It used to be thought that the mantle and the crust interacted

only in a relatively minor way. This work suggests that, at

least in certain circumstances, that's not true."

So what happened to the missing

continental crust?

In their study (Large-scale

Subduction of Continental Crust implied by India-Asia Mass-Balance

Calculation) published by Nature Geoscience the

researchers explain there were only a few places for the displaced

crust to go after the collision.

After ruling every single other possibility out, they concluded that

half of the continental crust involved in this colossal crash must

have sunk down into the hellish depths and recycled.

Some of the crust was thrust upward, forming the Himalayas, some was

eroded and deposited as enormous sedimentary deposits in the oceans,

and some was squeezed out the sides of the colliding plates, forming

Southeast Asia.

"The implication of our work is

that, if we're seeing the India-Asia collision system as an

ongoing process over Earth's history, there has been a

continuous mixing of the continental crustal elements back into

the mantle," said David Rowley, a professor in geophysical

sciences.

"And they can then be re-extracted

and seen in some of those volcanic materials that come out of

the mantle today."

|