|

by Jacob Bell

November

10, 2022

from

ClassicalWisdom Website

Perception as Illusion

Plato, along with his instructor Socrates, are often

recognized as the minds which began the western philosophical

tradition as we know it today.

Plato's theory of forms and the

Allegory of the Cave are not

only interesting within the history of philosophy, but hold

relevance in regards to both contemporary philosophy and science.

So relevant, in fact,

that a new theory in physics postulates a concept quite similar to

Plato's.

But before we get to that, let's take a quick moment to revisit

Plato's theory of forms...

Depiction of Plato's

Allegory of the Cave

Is Reality an

Illusion?

For Plato, the world as perceived isn't the ultimate reality.

The objects of everyday

life are but shadows of the forms. In the Allegory of the

Cave, Plato relates our false perception of the world of

experience to the idea of shadows on a wall.

Imagine that you were chained up in a cave in such a way that you

could only look at the wall in front of you.

You couldn't look

behind you or turn your head in any direction.

Behind you, in the

distance, is a roaring fire.

In front of the fire

are a variety of objects.

The shadows of those

objects are displayed on the wall in front of you.

Not only would you be

bored out of your mind, you would also be living in illusion...

If you knew no other life than that of the cave, the shadows would

seem to constitute real objects of reality for you. They wouldn't be

simple phantoms or shadows of something which is more real, they

would seem to be the most real, and they would make up your reality.

For Plato, this is

similar to our everyday experience...

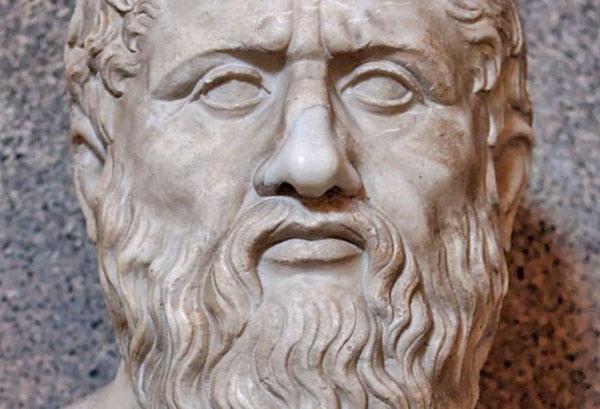

Bust of Plato

In the same way that the shadows on the wall don't constitute the

ultimate reality of the objects from which those shadows are

derived, the objects of everyday experience aren't a true or perfect

reflection of ultimate reality either.

The Forms

The forms, being the ultimate reality, are universal,

timeless, and perfect. The objects of experience are imperfect

imitations of the forms.

For example:

A mathematical

triangle is perfect in abstraction, but no perfect triangles can

be found in nature.

The triangles of our

experienced world are but imperfect reflections of the ideal

form of a triangle.

Just as the triangles of

experience are but imperfect reflections of the true form of a

triangle, it is the same with every object of perception, including

things like beauty.

Beauty has an

ideal form of which the beautiful things that we perceive are but

imperfect reflections.

Therefore, the world as

we perceive and experience it to be, is but an imperfect reflection

of the ultimate reality of forms.

Informational

Realism

Although this is an ancient theory, contemporary physics has renewed

the idea in a radical way.

The idea is called

information realism and was recently covered in an

article (Physics

is Pointing Inexorably to Mind) by Scientific

American.

Information realism

claims that the objects of everyday experience are not a part of

ultimate reality, but that they are perceptual illusions...

Instead, what is

considered to be the true or ultimate reality is the

underlying mathematics or information itself.

The matter which

allows us to perceive objects in everyday experience is merely

derived from the underlying information.

The information which

underlies the objects of experience is the ultimate reality.

Everything else is

but a perceptual illusion.

Information Realism,

just like Plato's theory of forms, uses the epistemological

method of rationalism, as opposed to empiricism, to come to such

conclusions.

Rationalists claims

that true knowledge of the world is derived through the use of

reason - independent of experience.

Empiricists claim

that true knowledge of the world is gained through experience

and the use of our senses.

Science and

Philosophy

Taking all of this into consideration, is the theory of

information realism a scientific one, or a philosophical

one?

I would argue that it is

philosophical in nature. In fact, many theories in contemporary

physics seem to be more philosophical than scientific.

Then again,

philosophy and science were at one time a

joint discipline - and even the great Isaac Newton was

considered to be natural philosopher.

Some of the challenges that have been raised against the theory

of forms, could also be raised against information realism.

One such challenge

regards,

the idea of an

ultimate reality that is beyond any possible experience

as unknowable in itself.

Is the world as experienced

an

illusion...?

In other words, if ultimate reality exists in a world beyond

ours, or if true reality is somehow beyond our scope of

experience,

How can we say

anything meaningful about it?

How do we know what

this ultimate reality is if we cannot study it in experience?

How do we even know

that there is an ideal world or ultimate reality which exists

beyond ours?

How do we know that

such a reality is more than an abstract or mathematical

artifact?

How can we test these

theories if the world posited by them is seemingly inaccessible?

It is difficult to make

sense out of such theories, which posit a reality beyond our

experience. It is difficult to say anything meaningful about an

ultimate reality which is supposedly more real than our world.

But it is ideas like

these that inspire movies such as

The Matrix, give philosophers

more to think about, and may eventually reunite science and

philosophy...

|