|

by Jenessa Duncombe February 27, 2019 from EOS Website

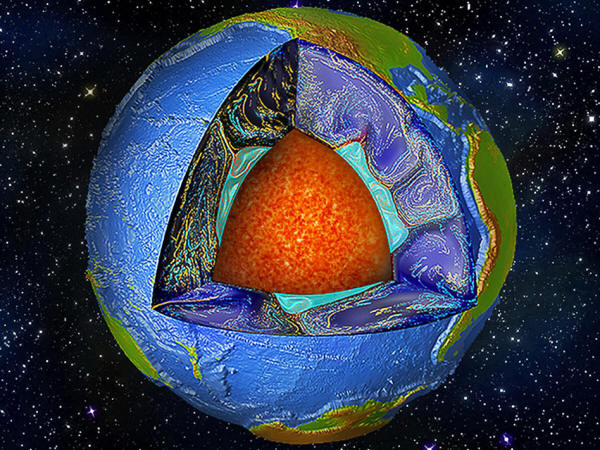

What lies below? A cutaway of Earth down to the liquid core shows the swirling mantle rock (dark blue). Made from a numerical convection model, the image shows mysterious structures underneath the Pacific Ocean that some researchers believe hold the clue to unlocking mysteries of Earth's past (light blue).

Credit:

Mingming Li/Arizona State University found two continent-sized structures that upend our picture of the mantle. What could their existence mean for us back on Earth's surface...?

The blobs are made of

rock, just like the rest of the mantle, but they may be hotter and

heavier and hold a key to unlocking the story of Earth's past.

Researchers had just invented a new way to peer inside Earth: When an earthquake shakes the planet, it lets out waves of energy in all directions. Scientists track those waves when they reach the surface and calculate where they came from.

By looking at the travel times of waves from many earthquakes, taken from thousands of instruments around the globe, scientists can reverse engineer a picture of Earth's interior.

The process is similar to

a doctor using an ultrasound device to image a fetus in the womb.

Credit: Sanne Cottaar

Scientists believe these

blobs play a role in many of the processes of the deep Earth,

including plate tectonics and volcanism.

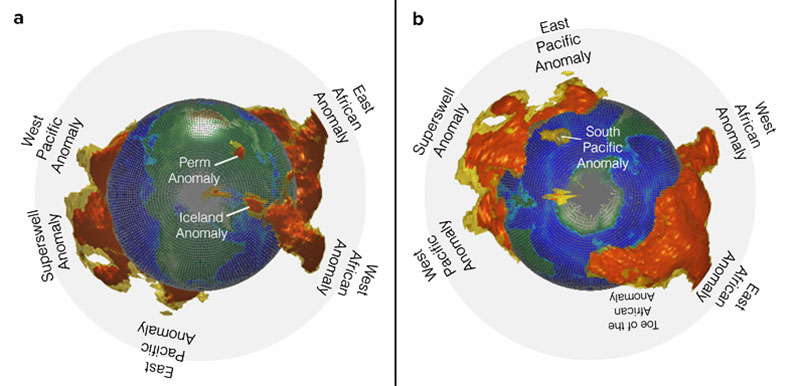

The slow-wave velocity zones are concentrated in two locations:

They appeared like,

Other researchers describe them as conical pits of gravel sitting "all on top of each other" or like giant sand piles.

The blobs are so large that if they sat on Earth's surface, the International Space Station would need to navigate around them.

There is little doubt that the blobs exist, yet scientists have no idea what they are.

A recent paper (Tidal Tomography constrains Earth's Deep-Mantle Buoyancy) said the blobs "remain enigmatic." Scientists can't even decide on what to call them.

They go by many names,

most commonly

LLSVP, which stands for 'large low shear velocity

provinces'.

The blobs, seen from the (a) North and (b) South Poles. The two-toned structures show the shapes of the blob based on the agreement of five different models (brown) and three different models (tan). Credit: Cottaar and Lekic, 2016,

https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggw324

Scientists are constantly

trying to come up with new ways to peek inside Earth indirectly.

Several recent studies in

cutting-edge techniques are bringing new insights to the table.

Are You Dense or

What?

leaves many "doors open"...

Most seismic readings cannot determine the density of the material because changes in wave velocity depend on multiple factors, such as rock composition.

Not

knowing the density leaves many "doors open," said mineral physicist

Dan Shim from Arizona State University.

Researchers have argued

back and forth about whether the masses are made of dense piles of

chemically unique rock or bouncy lava lamp plumes that are headed

for the crust above.

But Shim said that until the density of the blobs is understood,

The Kīlauea volcano on the Big Island in Hawaii comes from hot spot volcanism, which scientists believe could be linked to the blobs.

Credit: iStock.com/Frizi

Earth Doing the Wave

the entire planet flexes and stretches.

Although we're more familiar with ocean tides, the solid Earth experiences the same forces as our oceans. As the Sun and the Moon pull on Earth, the entire planet flexes and stretches.

In some places, the surface of Earth rises and falls by as much as 40 centimeters. Scientists can track this movement using highly sensitive GPS measurements.

A group of researchers led by Linguo Yuan at Academia Sinica in Taiwan analyzed measurements from GPS stations across the globe over 16 years and found that the Earth tide wasn't what they expected:

The tides, they wrote in their 2013 paper (The Tidal Displacement field at Earth's Surface determined using Global GPS Observations),

Harriet Lau, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University, heard about Yuan's work and saw an opportunity with the global data set.

These tides could fill in

the knowledge gap that traveling waves used in seismic tomography

could not.

She found that the models that fit the real-world data the best were those with blobs denser than the surrounding mantle.

These findings (Tidal

Tomography constrains Earth's Deep-Mantle Buoyancy), published in

Nature in

2017, argued that the blobs have some sort of "compositional

differences" than the rest of the mantle.

Normal modes reveal details that more conventional seismic methods miss but are,

Many seismologists analyze waves coming out of Earth, but not all waves act alike.

The images that map

Earth's interior use what's called body waves. Similar to sound

waves that travel through the atmosphere from someone's mouth to

another person's ear across the room, these waves travel through

Earth from one place to the next.

This type of wave is called a standing wave, and it's the type that shudders a violin string.

Earthquakes trigger both

types of waves, and seismometers detect them at the surface.

Her team analyzed records of ground movement in the days following large-magnitude earthquakes, looking for the low-frequency vibrations of standing waves.

Comparing their results with models, they found that the blobs must be less dense than the surrounding mantle to explain several constraints, like the shape of the core.

When asked how the two studies reconcile, the researchers suggested that both papers could be correct.

Perhaps the blobs are densest in a sliver right next to the core, a detail that Koelemeijer could not rule out in her analysis.

Harriet Lau echoed this suggestion.

partly because of their soft, lump-like shape in seismic tomography maps. But what if their structure was actually more delicate?

Despite the new 3-D imaging technology, he said the low-resolution images on the screen were off-putting.

In seismic tomography, researchers deal with similar problems.

The blobs received their nickname partly because of their soft, lump-like shape in seismic tomography maps.

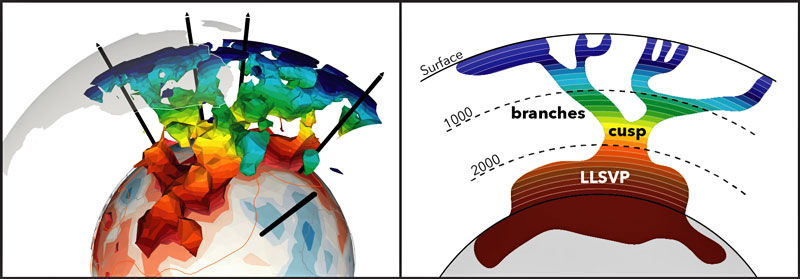

Last December, doctoral student Maria Tsekhmistrenko from the University of Oxford presented some of the most revealing images of the structures to date.

At a session at AGU's

Fall Meeting, Tsekhmistrenko showed her seismic tomography maps of

about half of the blob under Africa. The images come from an

extensive seismometer project that deployed sensors on the ocean

floor around Madagascar.

Taken together, the whole

structure looks like a tree that branches up to hot spot volcanoes

at the surface, said Tsekhmistrenko's adviser, Karin Sigloch.

Seismic tomography image from Maria Tsekhmistrenko African blob and the mantle plumes coming off of it (left). The blob, called LLSVP, sits at the base of the mantle, and slow-wave velocity regions above the blob could indicate plumes or upwelling. A simplified image of the structures is shown on the right.

Credit: Maria Tsekhmistrenko

Then she realized they were correct, even though,

Garnero, who saw the presentation, said that it was,

He added that scientists who study the movement of the inner Earth, called geodynamicists, may be excited to get their hands on Tsekhmistrenko's images.

Tsekhmistrenko has already heard from one geodynamicist planning to simulate the structures in a future model.

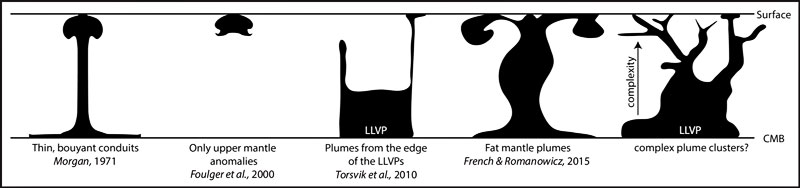

through several examples in the literature (Morgan, 1971, https://doi.org/10.1038/230042a0; Foulger et al., 2000, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-246x.2000.00245.x; Torsvik et al., 2010, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09216; French and Romanowicz, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14876).

Credit: Maria Tsekhmistrenko

Looking Inward

Mineral physicists, for example, measure how waves travel through rocks under extraordinary pressures to improve seismology models.

Geochemists scour Earth

to collect rocks from volcanoes, looking for clues of unique

chemical reservoirs that could be linked to the blobs. And modelers

construct intricate webs of code to evolve the mantle over billions

of years, simulating how the blobs came to form.

Earth is the only planet known to contain plate tectonics, and recent research (Biogeodynamics - Bridging the Gap between Surface and Deep Earth processes) has suggested that tectonics may help sustain life by delivering a steady stream of nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, to the surface.

And yet researchers aren't sure what causes plate tectonic movement, let alone the blobs.

"We literally don't know what they are, where they came from, how long they've been around, or what they do."

Ultimately, the road to uncovering the mysteries may be long, said Garnero.

Lau, who plans to study the blobs as she begins her professorship at the University of California, Berkeley, later this year, said she isn't fazed by the mystery.

|